3. River Leven

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

River Leven Catchment Initiative Synthesis of Current Knowledge to Help Identify Environmental Management Priorities to Improve the Water Environment

River Leven Catchment Initiative Synthesis of current knowledge to help identify environmental management priorities to improve the water environment EH , C ay a M Lind Photo credit: Published by CREW – Scotland’s Centre of Expertise for Waters. CREW connects research and policy, delivering objective and robust research and expert opinion to support the development and implementation of water policy in Scotland. CREW is a partnership between the James Hutton Institute and all Scottish Higher Education Institutes supported by MASTS. The Centre is funded by the Scottish Government. This document was produced by: Linda May, Jan Dick, Iain Gunn & Bryan Spears Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, Bush Estate, Penicuik, Midlothian EH26 OQB Please reference this report as follows: May, L., Dick, J., Gunn, I.D.M. & Spears, B. (2018) River Leven Catchment Initiative: Synthesis of current knowledge to help identify environmental management priorities to improve the water environment. CD2018/2. Available online at: crew. ac.uk/publications Dissemination status: Unrestricted Copyright: All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, modified or stored in a retrieval system without the prior written permission of CREW management. While every effort is made to ensure that the information given here is accurate, no legal responsibility is accepted for any errors, omissions or misleading statements. All statements, views and opinions expressed in this paper are attributable to the author(s) who contribute to the activities of CREW and do not necessarily represent those of the host institutions or funders. Acknowledgements: We thank staff at Scottish Environment Protection Agency, Forth Fisheries Trust, British Geological Survey and Fife Council for data and information provided. -

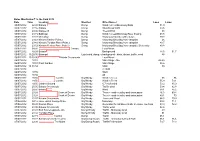

Noise Monitoring T in the Park 2012 Date Time Location Weather Other

Noise Monitoring T in the Park 2012 Date Time Location Weather Other Noise? Laeq Lmax 05/07/2012 22:45 Balado Damp Wind in trees/Motorway/Birds 51.9 05/07/2012 22:55 Balado Damp Birds/Road traffic 53.6 05/07/2012 23:06 Dalqueich Damp Trees/Wind 38 05/07/2012 23:15 Ballingall Damp Wind in trees/Motorway/River flowing 43.8 05/07/2012 23:23 Milnathort Damp Motorway/Attendees/No music 39.3 05/07/2012 23:43 Kinross Katrine Point 2 Damp Motorway/Shouting from campsite 46 05/07/2012 23:49 Kinross Toridon Place Point 2 Damp Motorway/Shouting from campsite 43.7 05/07/2012 23:52 Kinross Renton Place Point 3 Damp Motorway/Shouting from campsite/Generator 40.8 06/07/2012 09:50 , Carnbo Loud Music 06/07/2012 10:28 Balado Background 44.5 51.7 06/07/2012 10:29:36 Balangal Light wind, damp, o background - birds, distant traffic, wind 48 06/07/2012 10:35:00 Balado Crossroads Loud Music 06/07/2012 10:51 Main Stage - No 48-49 06/07/2012 10:51 Front Garden Main Stage 50.6 06/07/2012 10.53-54 NME 50 06/07/2012 KTWW 06/07/2012 10:55 Slam 06/07/2012 10:56 All 06/07/2012 19:50 Carnbo Dry/Windy Wind in Trees 55 86 06/07/2012 19:50 Carnbo Dry/Windy Wind in Trees 55.9 79.1 06/07/2012 19:50 Garden Ground Dry/Windy 6.7 ms/h wind 53.2 85.9 06/07/2012 20:50 Balado Crossroads Dry/Windy Traffic wind 59.4 82.8 06/07/2012 20:50 Balado Dry/Windy Wind 58.1 85.2 06/07/2012 23:28 Crook of Devon Dry/Windy Trees + road v rustley and snow patrol 46.3 69.4 06/07/2012 23:28 Crook of Devon Dry/Windy Trees + road v rustley and snow patrol 49.1 70 06/07/2012 23:57 Balado Crossroads -

Kinross-Shire Centre Kinross Scottish Charity SC004968 KY13 8AJ

Founding editor, Mrs Nan Walker, MBE Kinross Newsletter Founded in 1977 by Kinross Community Council ISSN 1757-4781 Published by Kinross Newsletter Limited, Company No. SC374361 Issue No 464 All profits given away to local good causes by The Kinross Community Council Newsletter, Charitable Company No. SC040913 www.kinrossnewsletter.org www.facebook.com/kinrossnewsletter July 2018 DEADLINE CONTENTS for the August Issue From the Editor ........................................................................... 2 5pm, Scottish Women’s Institutes. ....................................................... 2 Friday 13 July 2018 News and Articles ........................................................................ 3 Police Box .................................................................................. 17 for publication on Community Councils ................................................................. 18 Saturday 28 July 2018 Club & Community Group News ............................................... 27 Sport .......................................................................................... 43 Out & About. ............................................................................. 52 Contributions for inclusion in the Congratulations. ........................................................................ 54 Newsletter Church Information ................................................................... 55 The Newsletter welcomes items from community Playgroups and Toddlers........................................................... -

International Passenger Survey, 2008

UK Data Archive Study Number 5993 - International Passenger Survey, 2008 Airline code Airline name Code 2L 2L Helvetic Airways 26099 2M 2M Moldavian Airlines (Dump 31999 2R 2R Star Airlines (Dump) 07099 2T 2T Canada 3000 Airln (Dump) 80099 3D 3D Denim Air (Dump) 11099 3M 3M Gulf Stream Interntnal (Dump) 81099 3W 3W Euro Manx 01699 4L 4L Air Astana 31599 4P 4P Polonia 30699 4R 4R Hamburg International 08099 4U 4U German Wings 08011 5A 5A Air Atlanta 01099 5D 5D Vbird 11099 5E 5E Base Airlines (Dump) 11099 5G 5G Skyservice Airlines 80099 5P 5P SkyEurope Airlines Hungary 30599 5Q 5Q EuroCeltic Airways 01099 5R 5R Karthago Airlines 35499 5W 5W Astraeus 01062 6B 6B Britannia Airways 20099 6H 6H Israir (Airlines and Tourism ltd) 57099 6N 6N Trans Travel Airlines (Dump) 11099 6Q 6Q Slovak Airlines 30499 6U 6U Air Ukraine 32201 7B 7B Kras Air (Dump) 30999 7G 7G MK Airlines (Dump) 01099 7L 7L Sun d'Or International 57099 7W 7W Air Sask 80099 7Y 7Y EAE European Air Express 08099 8A 8A Atlas Blue 35299 8F 8F Fischer Air 30399 8L 8L Newair (Dump) 12099 8Q 8Q Onur Air (Dump) 16099 8U 8U Afriqiyah Airways 35199 9C 9C Gill Aviation (Dump) 01099 9G 9G Galaxy Airways (Dump) 22099 9L 9L Colgan Air (Dump) 81099 9P 9P Pelangi Air (Dump) 60599 9R 9R Phuket Airlines 66499 9S 9S Blue Panorama Airlines 10099 9U 9U Air Moldova (Dump) 31999 9W 9W Jet Airways (Dump) 61099 9Y 9Y Air Kazakstan (Dump) 31599 A3 A3 Aegean Airlines 22099 A7 A7 Air Plus Comet 25099 AA AA American Airlines 81028 AAA1 AAA Ansett Air Australia (Dump) 50099 AAA2 AAA Ansett New Zealand (Dump) -

RSPB Loch Leven on Saturday 8 August and Agricultural Awards Scheme Organised by Scottish Local Retailer Magazine

Founding editor, Mrs Nan Walker, MBE Kinross Newsletter Founded in 1977 by Kinross Community Council ISSN 1757-4781 Published by Kinross Newsletter Limited, Company No. SC374361 Issue No 431 www.kinrossnewsletter.org www.facebook.com/kinrossnewsletter July 2015 DEADLINE CONTENTS for the August Issue 5.00 pm, Friday From the Editor ..................................................................2 Letters ................................................................................2 17 July 2015 News and Articles ...............................................................4 for publication on Police Box ........................................................................14 Saturday 1 August 2015 Community Councils ........................................................15 Club & Community Group News .....................................25 Contributions for inclusion in the Sport .................................................................................36 Newsletter Out & About. ....................................................................41 The Newsletter welcomes items from community organisations and individuals for publication. This Gardens Open. ..................................................................43 is free of charge (we only charge for business News from the Rurals .......................................................44 advertising – see below right). All items may be Congratulations & Thanks ................................................44 subject to editing and we reserve the right not -

Kinross-Shire Partnership

Kinross Newsletter Founded in 1977 by Mrs Nan Walker, MBE ISSUE No 341 May 2007 www.kinrossnewsletter.org DEADLINE for the June Issue CONTENTS From the Editor ............................................................2 5.00 pm, Monday Letters ..........................................................................2 21 May 2007 News and Articles .........................................................4 for publication on High School Citizenship Cup..........................................9 Saturday 2 June 2007 Kinross-shire Partnership.............................................10 Police Box..................................................................12 Community Councils...................................................13 Contributions for inclusion in the Club & Community Group News .................................19 Newsletter Sport...........................................................................25 The Newsletter welcomes items from clubs, SWRI News ...............................................................29 community organisations and individuals for Nature.........................................................................30 publication. This is free of charge (we only charge for commercial advertising). All Hedgehog Blog............................................................32 items may be subject to editing. Please also Gardens Open..............................................................33 see our Letters Policy on page 2. Congratulations and Thanks ........................................34 -

The Barns Dalqueich Kinross

THE BARNS DALQUEICH KINROSS THE BARNS DALQUEICH, KINROSS, KY13 0RG Edinburgh Airport 27 miles, Perth 18 miles, Milnathort 3 miles, Kinross 3 miles Contemporary family home with open plan accommodation High specification fixtures and fittings throughout Stunning gardens and grounds with the North Queich Burn passing through 3 Integral double garage, adjoining stables and separate car port Grazing extending to about 5 acres with stabling Sitting / Dining Room. Kitchen / Family Room 4 Bedrooms (4 En Suite), Bedroom 5 / Study Utility and Boot Rooms, WC OUTSTANDING CONTEMPORARY FAMILY EPC = B HOME WITH STABLING AND 9.29 ACRES OF GARDENS, WOODLAND, AND GRAZING About 9.29 acres in all SITUATION Dalqueich is a small country hamlet, close to Kinross, a well connected and attractive town which offers a wide range of local facilities including shops, professional services, primary and secondary schooling, restaurants, a supermarket and two golf courses. As well as local state schooling, there are a good number of private schools within easy reach including Dollar Academy, Glenalmond, Strathallan, Craigclowan, Kilgraston in Perth and Kinross, and St Leonards in St Andrews. Dalqueich is in a highly accessible location. The M90 gives quick access to both Perth and Edinburgh. There is a Park and Ride service at Kinross with regular express coach services to Edinburgh and Perth. There is a train station at Inverkeithing (17 miles) with services into both Haymarket and Edinburgh Waverley, as well as a further Park and Ride service. Edinburgh Airport, situated on the western periphery of Edinburgh, has an extensive range of both domestic and international flights. -

April2015.Pdf

Founding editor, Mrs Nan Walker, MBE Kinross Newsletter Founded in 1977 by Kinross Community Council ISSN 1757-4781 Published by Kinross Newsletter Limited, Company No. SC374361 Issue No 428 www.kinrossnewsletter.org www.facebook.com/kinrossnewsletter April 2015 DEADLINE CONTENTS for the May Issue 5.00 pm, Friday From the Editor ..................................................................2 17 April 2015 Letters ................................................................................2 News and Articles ...............................................................4 for publication on Police Box ........................................................................14 Saturday 2 May 2015 Community Councils ........................................................15 Contributions for inclusion in the Club & Community Group News .....................................22 Newsletter Sport .................................................................................36 The Newsletter welcomes items from community News from the Rurals .......................................................44 organisations and individuals for publication. This Out & About. ....................................................................45 is free of charge (we only charge for business Gardens Open. ..................................................................48 advertising – see below right). All items may be Congratulations & Thanks ................................................49 subject to editing and we reserve the right not to publish -

Landscape Character Assessment Fife Landscape Evolution and Influences

Landscape Character Assessment – NatureScot 2019 LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT FIFE LANDSCAPE EVOLUTION AND INFLUENCES Landscape Evolution and Influences - Fife 1 Landscape Character Assessment – NatureScot 2019 CONTENTS 1. Introduction/Overview page 3 2. Physical Influences page 6 3. Human Influences page 13 4. Cultural Influences and Landscape Perception page 26 Title Page Photographs, clockwise from top left Isle of May National Nature Reserve. ©Lorne Gill/NatureScot Pittenweem and the East Neuk of Fife © P& A Macdonald/NatureScot Benarty Hill, Loch Leven ©Lorne Gill/NatureScot Anstruther and Cellardyke. ©Lorne Gill/NatureScot This document provides information on how the landscape of the local authority area has evolved. It complements the Landscape Character Type descriptions of the 2019 dataset. The original character assessment reports, part of a series of 30, mostly for a local authority area, included a “Background Chapter” on the formation of the landscape. These documents have been revised because feedback said they are useful, despite the fact that other sources of information are now readily available on the internet, unlike in the 1990’s when the first versions were produced. The content of the chapters varied considerably between the reports, and it has been restructured into a more standard format: Introduction, Physical Influences and Human Influences for all areas; and Cultural Influences sections for the majority. Some content variation still remains as the documents have been revised rather than rewritten, The information has been updated with input from the relevant Local Authorities. The historic and cultural aspects have been reviewed and updated by Historic Environment Scotland. Gaps in information have been filled where possible. -

Loch Leven Heritage Project

Kinross Newsletter Founded in 1977 by Mrs Nan Walker, MBE Issue No 357 October 2008 www.kinrossnewsletter.org ISSN 1757-4781 DEADLINE CONTENTS for the November Issue 2.00 pm, Monday From the Editor ............................................................2 20 October 2008 Letters ..........................................................................2 for publication on News and Articles .........................................................4 Police Box....................................................................8 Saturday 1 November 2008 Book Competition Winners............................................8 Community Councils.....................................................9 Contributions for inclusion in the Club & Community Group News .................................16 Newsletter Sport ..........................................................................22 The Newsletter welcomes items from clubs, News from the Rurals..................................................28 community organisations and individuals for Out & About...............................................................29 publication. This is free of charge (we only Gardens Open..............................................................31 charge for commercial advertising - see Congratulations and Thanks.........................................32 below right). All items may be subject to Church Information, Obituaries....................................33 editing. Please also see our Letters Policy on Playgroups & Nurseries...............................................35 -

The Place Names of Fife and Kinross

1 n tllif G i* THE PLACE NAMES OF FIFE AND KINROSS THE PLACE NAMES OF FIFE AND KINROSS BY W. J. N. LIDDALL M.A. EDIN., B.A. LOND. , ADVOCATE EDINBURGH WILLIAM GREEN & SONS 1896 TO M. J. G. MACKAY, M.A., LL.D., Advocate, SHERIFF OF FIFE AND KINROSS, AN ACCOMPLISHED WORKER IN THE FIELD OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH. INTRODUCTION The following work has two objects in view. The first is to enable the general reader to acquire a knowledge of the significance of the names of places around him—names he is daily using. A greater interest is popularly taken in this subject than is apt to be supposed, and excellent proof of this is afforded by the existence of the strange corruptions which place names are wont to assume by reason of the effort on the part of people to give some meaning to words otherwise unintelligible to them. The other object of the book is to place the results of the writer's research at the disposal of students of the same subject, or of those sciences, such as history, to which it may be auxiliary. The indisputable conclusion to which an analysis of Fife—and Kinross for this purpose may be considered a Fife— part of place names conducts is, that the nomen- clature of the county may be described as purely of Goidelic origin, that is to say, as belonging to the Irish branch of the Celtic dialects, and as perfectly free from Brythonic admixture. There are a few names of Teutonic origin, but these are, so to speak, accidental to the topography of Fife. -

Perth and Kinross Council Environment, Enterprise and Infrastructure Committee 3 6 September 2017

Securing the future • Improving services • Enhancing quality of life • Making the best use of public resources Council Building 2 High Street Perth PH1 5PH Thursday, 09 November 2017 A Meeting of the Environment, Enterprise and Infrastructure Committee will be held in the Council Chamber, 2 High Street, Perth, PH1 5PH on Wednesday, 08 November 2017 at 10:00 . If you have any queries please contact Committee Services on (01738) 475000 or email [email protected] . BERNADETTE MALONE Chief Executive Those attending the meeting are requested to ensure that all electronic equipment is in silent mode. Members: Councillor Colin Stewart (Convener) Councillor Michael Barnacle (Vice-Convener) Councillor Callum Purves (Vice-Convener) Councillor Alasdair Bailey Councillor Stewart Donaldson Councillor Dave Doogan Councillor Angus Forbes Councillor Anne Jarvis Councillor Grant Laing Councillor Murray Lyle Councillor Andrew Parrott Councillor Crawford Reid Councillor Willie Robertson Councillor Richard Watters Councillor Mike Williamson Page 1 of 294 Page 2 of 294 Environment, Enterprise and Infrastructure Committee Wednesday, 08 November 2017 AGENDA MEMBERS ARE REMINDED OF THEIR OBLIGATION TO DECLARE ANY FINANCIAL OR NON-FINANCIAL INTEREST WHICH THEY MAY HAVE IN ANY ITEM ON THIS AGENDA IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE COUNCILLORS’ CODE OF CONDUCT. 1 WELCOME AND APOLOGIE S 2 DECLARATIONS OF INTE REST 3 MINUTE OF MEETING OF THE ENVIRONMENT, ENT ERPRISE 5 - 10 AND INFRASTRUCTURE COMMITTEE OF 6 SEPTEMBER 2017 FOR APPROVAL AND SIGNATURE 4 PERTH CITY DEVELOPME NT