River Leven Catchment Initiative Synthesis of Current Knowledge to Help Identify Environmental Management Priorities to Improve the Water Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

March Newsletter

Founding editor, Kinross Newsletter Mrs Nan Walker, MBE Founded in 1977 by Kinross Community Council ISSN 1757-4781 Published by Kinross Newsletter Limited, Company No. SC374361 Issue No 493 All profits given away to local good causes by The Kinross Community Council Newsletter, Charitable Company No. SC040913 www.kinrossnewsletter.org www.facebook.com/kinrossnewsletter March 2021 DEADLINE CONTENTS for the April Issue From the Editor ........................................................................... 2 Thanks & Congratulations .......................................................... 3 5pm, Letters ......................................................................................... 4 Friday 12 March 2021 News ........................................................................................... 7 for publication on Church News ............................................................................. 25 Politicians .................................................................................. 26 Saturday 27 March 2021 Police Box .................................................................................. 32 Features .................................................................................... 35 Contributions For Inclusion Health and Wellbeing ................................................................ 43 In The Newsletter Emergency Contact Numbers .................................................... 46 Community Councils ................................................................. 49 The -

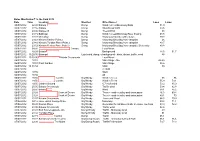

Noise Monitoring T in the Park 2012 Date Time Location Weather Other

Noise Monitoring T in the Park 2012 Date Time Location Weather Other Noise? Laeq Lmax 05/07/2012 22:45 Balado Damp Wind in trees/Motorway/Birds 51.9 05/07/2012 22:55 Balado Damp Birds/Road traffic 53.6 05/07/2012 23:06 Dalqueich Damp Trees/Wind 38 05/07/2012 23:15 Ballingall Damp Wind in trees/Motorway/River flowing 43.8 05/07/2012 23:23 Milnathort Damp Motorway/Attendees/No music 39.3 05/07/2012 23:43 Kinross Katrine Point 2 Damp Motorway/Shouting from campsite 46 05/07/2012 23:49 Kinross Toridon Place Point 2 Damp Motorway/Shouting from campsite 43.7 05/07/2012 23:52 Kinross Renton Place Point 3 Damp Motorway/Shouting from campsite/Generator 40.8 06/07/2012 09:50 , Carnbo Loud Music 06/07/2012 10:28 Balado Background 44.5 51.7 06/07/2012 10:29:36 Balangal Light wind, damp, o background - birds, distant traffic, wind 48 06/07/2012 10:35:00 Balado Crossroads Loud Music 06/07/2012 10:51 Main Stage - No 48-49 06/07/2012 10:51 Front Garden Main Stage 50.6 06/07/2012 10.53-54 NME 50 06/07/2012 KTWW 06/07/2012 10:55 Slam 06/07/2012 10:56 All 06/07/2012 19:50 Carnbo Dry/Windy Wind in Trees 55 86 06/07/2012 19:50 Carnbo Dry/Windy Wind in Trees 55.9 79.1 06/07/2012 19:50 Garden Ground Dry/Windy 6.7 ms/h wind 53.2 85.9 06/07/2012 20:50 Balado Crossroads Dry/Windy Traffic wind 59.4 82.8 06/07/2012 20:50 Balado Dry/Windy Wind 58.1 85.2 06/07/2012 23:28 Crook of Devon Dry/Windy Trees + road v rustley and snow patrol 46.3 69.4 06/07/2012 23:28 Crook of Devon Dry/Windy Trees + road v rustley and snow patrol 49.1 70 06/07/2012 23:57 Balado Crossroads -

Kinross-Shire Centre Kinross Scottish Charity SC004968 KY13 8AJ

Founding editor, Mrs Nan Walker, MBE Kinross Newsletter Founded in 1977 by Kinross Community Council ISSN 1757-4781 Published by Kinross Newsletter Limited, Company No. SC374361 Issue No 464 All profits given away to local good causes by The Kinross Community Council Newsletter, Charitable Company No. SC040913 www.kinrossnewsletter.org www.facebook.com/kinrossnewsletter July 2018 DEADLINE CONTENTS for the August Issue From the Editor ........................................................................... 2 5pm, Scottish Women’s Institutes. ....................................................... 2 Friday 13 July 2018 News and Articles ........................................................................ 3 Police Box .................................................................................. 17 for publication on Community Councils ................................................................. 18 Saturday 28 July 2018 Club & Community Group News ............................................... 27 Sport .......................................................................................... 43 Out & About. ............................................................................. 52 Contributions for inclusion in the Congratulations. ........................................................................ 54 Newsletter Church Information ................................................................... 55 The Newsletter welcomes items from community Playgroups and Toddlers........................................................... -

RSPB Loch Leven on Saturday 8 August and Agricultural Awards Scheme Organised by Scottish Local Retailer Magazine

Founding editor, Mrs Nan Walker, MBE Kinross Newsletter Founded in 1977 by Kinross Community Council ISSN 1757-4781 Published by Kinross Newsletter Limited, Company No. SC374361 Issue No 431 www.kinrossnewsletter.org www.facebook.com/kinrossnewsletter July 2015 DEADLINE CONTENTS for the August Issue 5.00 pm, Friday From the Editor ..................................................................2 Letters ................................................................................2 17 July 2015 News and Articles ...............................................................4 for publication on Police Box ........................................................................14 Saturday 1 August 2015 Community Councils ........................................................15 Club & Community Group News .....................................25 Contributions for inclusion in the Sport .................................................................................36 Newsletter Out & About. ....................................................................41 The Newsletter welcomes items from community organisations and individuals for publication. This Gardens Open. ..................................................................43 is free of charge (we only charge for business News from the Rurals .......................................................44 advertising – see below right). All items may be Congratulations & Thanks ................................................44 subject to editing and we reserve the right not -

Kinross-Shire

Kinross Newsletter Founded in 1977 by Mrs Nan Walker, MBE Published by Kinross Newsletter Limited, Company No. SC374361 Issue No 388 August 2011 www.kinrossnewsletter.org ISSN 1757-4781 DEADLINE CONTENTS for the September Issue From the Editor ............................................................ 2 2.00 pm, Monday Letters ......................................................................... 2 22 August 2011 News and Articles ........................................................ 5 for publication on Police Box...................................................................15 Community Councils....................................................16 Saturday 3 September 2011 Club & Community Group News .................................21 Sport ..........................................................................30 Contributions for inclusion in the Out & About................................................................37 Newsletter Gardens Open. .............................................................39 The Newsletter welcomes items from clubs, Congratulations and Thanks..........................................40 community organisations and individuals for Kinross High School Awards ........................................41 publication. This is free of charge (we only Church Information......................................................43 charge for commercial advertising - see Playgroups & Nurseries................................................45 below right). All items may be subject to Notices........................................................................46 -

Kinross-Shire

Kinross Newsletter Founded in 1977 by Kinross Community Council. Founding Editor: Mrs Nan Walker, MBE Published by Kinross Newsletter Limited, Company No. SC374361 Issue No 407 May 2013 www.kinrossnewsletter.org ISSN 1757-4781 DEADLINE CONTENTS for the June Issue 5.00 pm, Friday From the Editor ............................................................ 2 17 May 2013 Letters ......................................................................... 2 for publication on News and Articles ........................................................ 3 Police Box...................................................................13 Saturday 1 June 2013 Community Councils....................................................14 Club & Community Group News .................................23 Contributions for inclusion in the Sport ..........................................................................37 Newsletter News from the Rurals ..................................................43 The Newsletter welcomes items from community Out & About................................................................44 organisations and individuals for publication. Gardens Open. .............................................................46 This is free of charge (we only charge for Congratulations & Thanks. ...........................................47 business advertising – see below right). All items Church Information & Obituaries..................................48 may be subject to editing and we reserve the right not to publish an item. Please also -

Kinross-Shire Partnership

Kinross Newsletter Founded in 1977 by Mrs Nan Walker, MBE ISSUE No 341 May 2007 www.kinrossnewsletter.org DEADLINE for the June Issue CONTENTS From the Editor ............................................................2 5.00 pm, Monday Letters ..........................................................................2 21 May 2007 News and Articles .........................................................4 for publication on High School Citizenship Cup..........................................9 Saturday 2 June 2007 Kinross-shire Partnership.............................................10 Police Box..................................................................12 Community Councils...................................................13 Contributions for inclusion in the Club & Community Group News .................................19 Newsletter Sport...........................................................................25 The Newsletter welcomes items from clubs, SWRI News ...............................................................29 community organisations and individuals for Nature.........................................................................30 publication. This is free of charge (we only charge for commercial advertising). All Hedgehog Blog............................................................32 items may be subject to editing. Please also Gardens Open..............................................................33 see our Letters Policy on page 2. Congratulations and Thanks ........................................34 -

April2015.Pdf

Founding editor, Mrs Nan Walker, MBE Kinross Newsletter Founded in 1977 by Kinross Community Council ISSN 1757-4781 Published by Kinross Newsletter Limited, Company No. SC374361 Issue No 428 www.kinrossnewsletter.org www.facebook.com/kinrossnewsletter April 2015 DEADLINE CONTENTS for the May Issue 5.00 pm, Friday From the Editor ..................................................................2 17 April 2015 Letters ................................................................................2 News and Articles ...............................................................4 for publication on Police Box ........................................................................14 Saturday 2 May 2015 Community Councils ........................................................15 Contributions for inclusion in the Club & Community Group News .....................................22 Newsletter Sport .................................................................................36 The Newsletter welcomes items from community News from the Rurals .......................................................44 organisations and individuals for publication. This Out & About. ....................................................................45 is free of charge (we only charge for business Gardens Open. ..................................................................48 advertising – see below right). All items may be Congratulations & Thanks ................................................49 subject to editing and we reserve the right not to publish -

Loch Leven Heritage Project

Kinross Newsletter Founded in 1977 by Mrs Nan Walker, MBE Issue No 357 October 2008 www.kinrossnewsletter.org ISSN 1757-4781 DEADLINE CONTENTS for the November Issue 2.00 pm, Monday From the Editor ............................................................2 20 October 2008 Letters ..........................................................................2 for publication on News and Articles .........................................................4 Police Box....................................................................8 Saturday 1 November 2008 Book Competition Winners............................................8 Community Councils.....................................................9 Contributions for inclusion in the Club & Community Group News .................................16 Newsletter Sport ..........................................................................22 The Newsletter welcomes items from clubs, News from the Rurals..................................................28 community organisations and individuals for Out & About...............................................................29 publication. This is free of charge (we only Gardens Open..............................................................31 charge for commercial advertising - see Congratulations and Thanks.........................................32 below right). All items may be subject to Church Information, Obituaries....................................33 editing. Please also see our Letters Policy on Playgroups & Nurseries...............................................35 -

Portmoak Community Council

Portmoak Community Council Draft Minutes of Meeting held on 14th June 2016 at Portmoak School 1. Attendance: CCllrs: B Calderwood (Deputy Chair and Treasurer); R Cairncross (Secretary); T Smith; D Morris; and C Vlasto; and WCllrs: M Barnacle; and J Giacopazzi; and 8 members of the public. Apologies: CCllrs: M Strang Steel (Chairman); A Robertson; and S Forde; and WCllrs D Cuthbert and W Robertson; and Police Scotland. 2. Approval of previous Minutes: The draft Minute of the meeting held in May 2016 was approved. 3. Matters Arising from Previous Minutes: 5.0 PKC Public Transport Consultation: Stagecoach Route 201 which links Kinross to Glenrothes via the five Portmoak settlements was subsidised and was part of a current review on Kinross-shire public transport by PKC. At the open consultation forum hosted by PKC, the CC and several residents had reflected views from Portmoak on the value of route 201. WCllrs were asked to clarify if the burden of subsidy fell only on PKC or did Fife Council make a contribution. 6.0 Local Boundary Commission: The recommendation of the Commission to Scottish Ministers to retain the boundaries of the existing Ward 8 (Kinross-shire) and its representation by four 4 ward councillors was warmly welcomed. If the anticipated support for this decision from PKC was sent to the Scottish Government, the CC would also write in support. 8.1 Boulders restricting passage of essential agricultural machinery on the Dryside Road at Muirs of Kinnesswood. The land on both sides of the carriageway was owned by a local resident. PKC did not feel it had a locus in resolving this longstanding matter. -

The Place Names of Fife and Kinross

1 n tllif G i* THE PLACE NAMES OF FIFE AND KINROSS THE PLACE NAMES OF FIFE AND KINROSS BY W. J. N. LIDDALL M.A. EDIN., B.A. LOND. , ADVOCATE EDINBURGH WILLIAM GREEN & SONS 1896 TO M. J. G. MACKAY, M.A., LL.D., Advocate, SHERIFF OF FIFE AND KINROSS, AN ACCOMPLISHED WORKER IN THE FIELD OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH. INTRODUCTION The following work has two objects in view. The first is to enable the general reader to acquire a knowledge of the significance of the names of places around him—names he is daily using. A greater interest is popularly taken in this subject than is apt to be supposed, and excellent proof of this is afforded by the existence of the strange corruptions which place names are wont to assume by reason of the effort on the part of people to give some meaning to words otherwise unintelligible to them. The other object of the book is to place the results of the writer's research at the disposal of students of the same subject, or of those sciences, such as history, to which it may be auxiliary. The indisputable conclusion to which an analysis of Fife—and Kinross for this purpose may be considered a Fife— part of place names conducts is, that the nomen- clature of the county may be described as purely of Goidelic origin, that is to say, as belonging to the Irish branch of the Celtic dialects, and as perfectly free from Brythonic admixture. There are a few names of Teutonic origin, but these are, so to speak, accidental to the topography of Fife. -

Response to Perth and Kinross Ldp Further Information Request 03 – Housing Land Requirement/Supply

RESPONSE TO PERTH AND KINROSS LDP FURTHER INFORMATION REQUEST 03 – HOUSING LAND REQUIREMENT/SUPPLY JANUARY 2019 Homes for Scotland (HFS) is the voice of the home building industry in Scotland, representing some 200 companies and organisations which together deliver the majority of the country’s new homes. We are committed to improving the quality of living in Scotland by providing this and future generations of Scots with warm, energy-efficient, sustainable homes in places people want to live. HFS makes submissions on national and local government policy issues affecting the industry. Its views are endorsed by committees and advisory groups utilising the skills and expertise of key representatives drawn from our member companies. Homes for Scotland Page 1 2019 01 30 – HfS Response to P&K FIR 03 RESPONSE TO PERTH AND KINROSS LDP FURTHER INFORMATION REQUEST 03 – HOUSING LAND REQUIREMENT/SUPPLY Introduction 1. Homes for Scotland (HFS) welcomes the opportunity to comment on Perth and Kinross’s Further Information Request (FIR) response. These submissions have been reviewed and agreed by Homes for Scotland’s East Central Area Committee. Evidence Base 2. Homes for Scotland is pleased that the 2018 Housing Land Audit (HLA) could be agreed without dispute as set out in the Council’s response. The now published Audit provides both an up to date position which includes agreed programming for all proposed LDP allocations and a well presented, rich source of other relevant information. 3. The housing land supply set out in the Council’s response is now derived from a number of sources, according to the footnotes, including the 2016 HLA, the 2017 HLA, additional allocations referred to in the Housing Background Paper (November 2017) and programming for these sites as set out in the 2018 HLA.