Language Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The English Language: Did You Know?

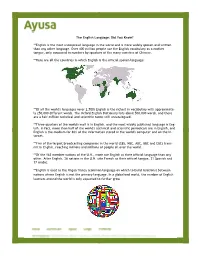

The English Language: Did You Know? **English is the most widespread language in the world and is more widely spoken and written than any other language. Over 400 million people use the English vocabulary as a mother tongue, only surpassed in numbers by speakers of the many varieties of Chinese. **Here are all the countries in which English is the official spoken language: **Of all the world's languages (over 2,700) English is the richest in vocabulary with approximate- ly 250,000 different words. The Oxford English Dictionary lists about 500,000 words, and there are a half-million technical and scientific terms still uncatalogued. **Three-quarters of the world's mail is in English, and the most widely published language is Eng- lish. In fact, more than half of the world's technical and scientific periodicals are in English, and English is the medium for 80% of the information stored in the world's computer and on the In- ternet. **Five of the largest broadcasting companies in the world (CBS, NBC, ABC, BBC and CBC) trans- mit in English, reaching millions and millions of people all over the world. **Of the 163 member nations of the U.N., more use English as their official language than any other. After English, 26 nations in the U.N. cite French as their official tongue, 21 Spanish and 17 Arabic. **English is used as the lingua franca (common language on which to build relations) between nations where English is not the primary language. In a globalized world, the number of English learners around the world is only expected to further grow. -

Early Modern English

Mrs. Halverson: English 9A Intro to Shakespeare’s Language: Early Modern English Romeo and Juliet was written around 1595, when William Shakespeare was about 31 years old. In Shakespeare's day, England was just barely catching up to the Renaissance that had swept over Europe beginning in the 1400s. But England's theatrical performances soon put the rest of Europe to shame. Everyone went to plays, and often more than once a week. There you were not only entertained but also exposed to an explosion of new phrases and words entering the English language for overseas and from the creative minds of Shakespeare and his contemporaries. The language Shakespeare uses in his plays is known as Early Modern English, and is approximately contemporaneous with the writing of the King James Bible. Believe it or not, much of Shakespeare's vocabulary is still in use today. For instance, Howard Richler in Take My Words noted the following phrases originated with Shakespeare: without rhyme or reason flesh and blood in a pickle with bated breath vanished into thin air budge an inch more sinned against than sinning fair play playing fast and loose brevity is the soul of wit slept a wink foregone conclusion breathing your last dead as a door-nail point your finger the devil incarnate send me packing laughing-stock bid me good riddance sorry sight heart of gold come full circle Nonetheless, Shakespeare does use words or forms of words that have gone out of use. Here are some guidelines: 1) Shakespeare uses some personal pronouns that have become archaic. -

Influences on the Development of Early Modern English

Influences on the Development of Early Modern English Kyli Larson Wright This article covers the basic social, historical, and linguistic influences that have transformed the English language. Research first describes components of Early Modern English, then discusses how certain factors have altered the lexicon, phonology, and other components. Though there are many factors that have shaped English to what it is today, this article only discusses major factors in simple and straightforward terms. 72 Introduction The history of the English language is long and complicated. Our language has shifted, expanded, and has eventually transformed into the lingua franca of the modern world. During the Early Modern English period, from 1500 to 1700, countless factors influenced the development of English, transforming it into the language we recognize today. While the history of this language is complex, the purpose of this article is to determine and map out the major historical, social, and linguistic influences. Also, this article helps to explain the reasons for their influence through some examples and evidence of writings from the Early Modern period. Historical Factors One preliminary historical event that majorly influenced the development of the language was the establishment of the print- ing press. Created in 1476 by William Caxton at Westminster, London, the printing press revolutionized the current language form by creating a means for language maintenance, which helped English gravitate toward a general standard. Manuscripts could be reproduced quicker than ever before, and would be identical copies. Because of the printing press spelling variation would eventually decrease (it was fixed by 1650), especially in re- ligious and literary texts. -

Some English Words Illustrating the Great Vowel Shift. Ca. 1400 Ca. 1500 Ca. 1600 Present 'Bite' Bi:Tə Bəit Bəit

Some English words illustrating the Great Vowel Shift. ca. 1400 ca. 1500 ca. 1600 present ‘bite’ bi:tә bәit bәit baIt ‘beet’ be:t bi:t bi:t bi:t ‘beat’ bɛ:tә be:t be:t ~ bi:t bi:t ‘abate’ aba:tә aba:t > abɛ:t әbe:t әbeIt ‘boat’ bɔ:t bo:t bo:t boUt ‘boot’ bo:t bu:t bu:t bu:t ‘about’ abu:tә abәut әbәut әbaUt Note that, while Chaucer’s pronunciation of the long vowels was quite different from ours, Shakespeare’s pronunciation was similar enough to ours that with a little practice we would probably understand his plays even in the original pronuncia- tion—at least no worse than we do in our own pronunciation! This was mostly an unconditioned change; almost all the words that appear to have es- caped it either no longer had long vowels at the time the change occurred or else entered the language later. However, there was one restriction: /u:/ was not diphthongized when followed immedi- ately by a labial consonant. The original pronunciation of the vowel survives without change in coop, cooper, droop, loop, stoop, troop, and tomb; in room it survives in the speech of some, while others have shortened the vowel to /U/; the vowel has been shortened and unrounded in sup, dove (the bird), shove, crumb, plum, scum, and thumb. This multiple split of long u-vowels is the most signifi- cant IRregularity in the phonological development of English; see the handout on Modern English sound changes for further discussion. -

Transatlantic Variation in English Adverb Placement

Language Variation and Change, 25 (2013), 179–200. © Cambridge University Press, 2013 0954-3945/13 $16.00 doi:10.1017/S0954394513000082 Transatlantic variation in English adverb placement C ATHLEEN W ATERS University of Toronto ABSTRACT This study examines the placement of an adverb with respect to a modal or perfect auxiliary in English (e.g., It might potentially escape / It potentially might escape). The data are drawn from two large, socially stratified corpora of vernacular English (Toronto, Canada, and York, England) and thus allow a cross-dialect perspective on linguistic and social correlates. Using quantitative sociolinguistic methods, I demonstrate similarity in the varieties, with the postauxiliary position generally strongly favored. Of particular importance is the structure of the auxiliary phrase; when a modal is followed by the perfect auxiliary (e.g., It might have escaped), the rates of preauxiliary adverb placement are considerably higher. As the variation is chiefly correlated with linguistic, rather than social factors, I apply recent proposals from Generative syntax to further understand the grammar of the phenomenon. However, the evidence suggests that the variability seen here is a result of postsyntactic, rather than syntactic, processes. Quantitative sociolinguistic study of adverbs has been limited, and much of the comparative work that has been undertaken on English has focused solely on morphological variation of the suffix -ly (Aijmer, 2009; Algeo, 2006; Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad, & Finegan, 1999; Opdahl, 2000). This work addresses the lacuna by examining a facet of adverb placement in two varieties of English using data from large, socially stratified corpora of vernacular English (described herein). -

A Corpus·Based Investigation of Xhosa English In

A CORPUS·BASED INVESTIGATION OF XHOSA ENGLISH IN THE CLASSROOM SETTING A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS of RHODES UNIVERSITY by CANDICE LEE PLATT January 2004 Supervisor: Professor V.A de K1erk ABSTRACT This study is an investigation of Xhosa English as used by teachers in the Grahamstown area of the Eastern Cape. The aims of the study were firstly, to compile a 20 000 word mini-corpus of the spoken English of Xhosa mother tongue teachers in Grahamstown, and to use this data to describe the characteristics of Xhosa English used in the classroom context; and secondly, to assess the usefulness of a corpus-based approach to a study of this nature. The English of five Xhosa mother-tongue teachers was investigated. These teachers were recorded while teaching in English and the data was then transcribed for analysis. The data was analysed using Wordsmith Tools to investigate patterns in the teachers' language. Grammatical, lexical and discourse patterns were explored based on the findings of other researchers' investigations of Black South African English and Xhosa English. In general, many of the patterns reported in the literature were found in the data, but to a lesser extent than reported in literature which gave quantitative information. Some features not described elsewhere were also found . The corpus-based approach was found to be useful within the limits of pattern matching. 1I TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vi CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION 1.1 CORPORA 1 1.2 BLACK SOUTH -

Syntactic Changes in English Between the Seventeenth Century and The

I Syntactic Changes in English between the Seventeenth Century and the Twentieth Century as Represented in Two Literary Works: William Shakespeare's Play The Merchant of Venice and George Bernard Shaw's Play Arms and the Man التغيرات النحوية في اللغة اﻹنجليزية بين القرن السابع عشر و القرن العشرين ممثلة في عملين أدبيين : مسرحية تاجر البندقيه لوليام شكسبيرو مسرحية الرجل والسﻻح لجورج برنارد شو By Eman Mahmud Ayesh El-Abweni Supervised by Prof. Zakaria Ahmad Abuhamdia A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master’s Degree in English Language and Literature Department of English Language and Literature Faculty of Arts and Sciences Middle East University January, 2018 II III IV Acknowledgments First and above all, the whole thanks and glory are for the Almighty Allah with His Mercy, who gave me the strength and fortitude to finish my thesis. I would like to express my trustworthy gratitude and appreciation for my supervisor Professor Zakaria Ahmad Abuhamdia for his unlimited guidance and supervision. I have been extremely proud to have a supervisor who appreciated my work and responded to my questions either face- to- face, via the phone calls or, SMS. Without his support my thesis, may not have been completed successfully. Also, I would like to thank the committee members for their comments and guidance. My deepest and great gratitude is due to my parents Mahmoud El-Abweni and Intisar El-Amayreh and my husband Amjad El-Amayreh who have supported and encouraged me to reach this stage. In addition, my appreciation is extended to my brothers Ayesh, Yousef and my sisters Saja and Noor for their support and care during this period, in addition to my beloved children Mohammad and Aded El-Rahman who have been a delight. -

The for Ma Tion of the Self. Nietz Sche and Com Plex

The Forma tion of the Self. Nietz sche and Complex ity Paul Cilliers,1 Tanya de Villiers and Vasti Roodt De part ment of Phi los o phy, Uni ver sity of Stellenbosch, Pri vate Bag X1, Matieland, 7602, South Af rica Ab stract: The purpose of this arti cle is to exam ine the rela ti on ship be tween the form a- tion of the self and the worldly ho rizon within which this self achieves its meaning. Our in quiry takes place from two per spec tives: the first de rived from the Nietzschean analy sis of how one becom es what one is; the other from current devel op m ents in com plexit y theory. This two-angled approach opens up differ ent, yet relat ed dim ensions of a non-essentialist un dersta nd - ing of the self that is nonethe les s nei ther arbi tra ry nor de ter minis ti c. Indeed, at the meet ing point of these two per spec tives on the self lies a concep ti on of a dynam ic, worldly self, whose iden tity is bound up with its ap pearance in a world shared with oth ers. Af ter exam ining this argu ment from the respec tive view points offered by Nietzsche and com plexit y theory, the arti cle con- cludes with a con sid er ation of some of the po lit i cal and eth i cal impli ca tions of repre sent ing our situatedness within a shared hum an dom ain as a con di- tion for self-formation. -

The Early Middle English Reflexes of Germanic *Ik ‘I’: Unpacking the Changes

Edinburgh Research Explorer The early Middle English reflexes of Germanic *ik ‘I’: unpacking the changes Citation for published version: Lass, R & Laing, M 2013, 'The early Middle English reflexes of Germanic *ik ‘I’: unpacking the changes', Folia Linguistica Historica, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 93-114. https://doi.org/10.1515/flih.2013.004 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1515/flih.2013.004 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Folia Linguistica Historica Publisher Rights Statement: © Lass, R., & Laing, M. (2013). The early Middle English reflexes of Germanic *ik ‘I’: unpacking the changes. Folia Linguistica Historica, 34(1), 93-114. 10.1515/flih.2013.004 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 The early Middle English reflexes of Germanic *ik ‘I’: Unpacking the changes1 Roger Lass & Margaret Laing University of Edinburgh The phonological shape of the PDE first-person nominative singular pronoun ‘I’ is assumed to have a simple history. -

Are You Eligible for the Senior Citizen Homeowner

Please read but do not submit with your application Homeowner Tax Benefits Initial Application Instructions for Tax Year 2018/19 Please note: If the property has a life estate, only the individual retaining the life estate can apply. If the property is held in a trust, only the qualifying beneficiary/trustee can apply. Are you eligible for the Senior Citizen Homeowner Exemption (SCHE)? • Will all owners be 65 years of age or older by December 31, 2018? n Yes n No OR • If you own your property with either a spouse or sibling, will at least one of you be 65 years of age or older by December 31, 2018? • Will you have owned this property for at least 12 consecutive months prior n Yes n No to the date of filing this application? • Is the property the primary residence for ALL senior owners and their spouses? n Yes n No (All owners must reside on the property unless they are legally separated, divorced, abandoned or residing in a health care facility.*) *If an owner is residing in a health care facility, please submit documentation including total cost of care at the facility. • Is the Total Combined Income (TCI) for all owners and spouses $37,399 or less, n Yes n No regardless of where they live? (The income of a spouse may be excluded if he or she is absent from the residence due to divorce, legal separation or abandonment.) If you have answered NO to any of these questions, you MAY NOT be eligible for the Senior Citizen Homeowner Exemption. -

Personal Pronouns, Pronoun-Antecedent Agreement, and Vague Or Unclear Pronoun References

Personal Pronouns, Pronoun-Antecedent Agreement, and Vague or Unclear Pronoun References PERSONAL PRONOUNS Personal pronouns are pronouns that are used to refer to specific individuals or things. Personal pronouns can be singular or plural, and can refer to someone in the first, second, or third person. First person is used when the speaker or narrator is identifying himself or herself. Second person is used when the speaker or narrator is directly addressing another person who is present. Third person is used when the speaker or narrator is referring to a person who is not present or to anything other than a person, e.g., a boat, a university, a theory. First-, second-, and third-person personal pronouns can all be singular or plural. Also, all of them can be nominative (the subject of a verb), objective (the object of a verb or preposition), or possessive. Personal pronouns tend to change form as they change number and function. Singular Plural 1st person I, me, my, mine We, us, our, ours 2nd person you, you, your, yours you, you, your, yours she, her, her, hers 3rd person he, him, his, his they, them, their, theirs it, it, its Most academic writing uses third-person personal pronouns exclusively and avoids first- and second-person personal pronouns. MORE . PRONOUN-ANTECEDENT AGREEMENT A personal pronoun takes the place of a noun. An antecedent is the word, phrase, or clause to which a pronoun refers. In all of the following examples, the antecedent is in bold and the pronoun is italicized: The teacher forgot her book. -

Department of English and American Studies English Language And

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Jana Krejčířová Australian English Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: PhDr. Kateřina Tomková, Ph. D. 2016 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor PhDr. Kateřina Tomková, Ph.D. for her patience and valuable advice. I would also like to thank my partner Martin Burian and my family for their support and understanding. Table of Contents Abbreviations ........................................................................................................... 6 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 7 1. AUSTRALIA AND ITS HISTORY ................................................................. 10 1.1. Australia before the arrival of the British .................................................... 11 1.1.1. Aboriginal people .............................................................................. 11 1.1.2. First explorers .................................................................................... 14 1.2. Arrival of the British .................................................................................... 14 1.2.1. Convicts ............................................................................................. 15 1.3. Australia in the