Living with Fear Were Made Possible by Grants from the John D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phytoplankton Dynamics in the Congo River

Freshwater Biology (2016) doi:10.1111/fwb.12851 Phytoplankton dynamics in the Congo River † † † JEAN-PIERRE DESCY*, ,FRANCßOIS DARCHAMBEAU , THIBAULT LAMBERT , ‡ § † MAYA P. STOYNEVA-GAERTNER , STEVEN BOUILLON AND ALBERTO V. BORGES *Research Unit in Organismal Biology (URBE), University of Namur, Namur, Belgium † Unite d’Oceanographie Chimique, UniversitedeLiege, Liege, Belgium ‡ Department of Botany, University of Sofia St. Kl. Ohridski, Sofia, Bulgaria § Department of Earth & Environmental Sciences, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium SUMMARY 1. We report a dataset of phytoplankton in the Congo River, acquired along a 1700-km stretch in the mainstem during high water (HW, December 2013) and falling water (FW, June 2014). Samples for phytoplankton analysis were collected in the main river, in tributaries and one lake, and various relevant environmental variables were measured. Phytoplankton biomass and composition were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography analysis of chlorophyll a (Chl a) and marker pigments and by microscopy. Primary production measurements were made using the 13C incubation technique. In addition, data are also reported from a 19-month regular sampling (bi-monthly) at a fixed station in the mainstem of the upper Congo (at the city of Kisangani). 2. Chl a concentrations differed between the two periods studied: in the mainstem, they varied À À between 0.07 and 1.77 lgL 1 in HW conditions and between 1.13 and 7.68 lgL 1 in FW conditions. The relative contribution to phytoplankton biomass from tributaries (mostly black waters) and from a few permanent lakes was low, and the main confluences resulted in phytoplankton dilution. Based on marker pigment concentration, green algae (both chlorophytes and streptophytes) dominated in the mainstem in HW, whereas diatoms dominated in FW; cryptophytes and cyanobacteria were more abundant but still relatively low in the FW period, both in the tributaries and in the main channel. -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Report of the Interim Chairperson of the Commission of the African Union on the Situation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Drc)

AFRICAN UNION UNION AFRICAINE UNIÃO AFRICANA P. O. Box 3243, Addis Ababa, ETHIOPIA Tel.: (251-1) 513822 Fax: (251-1) 519321 Email: [email protected] EIGHTY SIXTH ORDINARY SESSION OF THE CENTRAL ORGAN OF THE MECHANISM FOR CONFLICT PREVENTION, MANAGEMENT AND RESOLUTION 29 October 2002 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Central Organ/MEC/AMB/2 (LXXXVI) REPORT OF THE INTERIM CHAIRPERSON OF THE COMMISSION OF THE AFRICAN UNION ON THE SITUATION IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO (DRC) Central Organ/MEC/AMB/2 (LXXXVI) Page 1 REPORT OF THE INTERIM CHAIRPERSON OF THE COMMISSION OF THE AFRICAN UNION ON THE SITUATION IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO (DRC) I. INTRODUCTION 1. At the 76th Ordinary Session of the OAU Council of Ministers held in Durban, South Africa, from 4 to 6 July 2002, I reported on the development of the Peace Process in the DRC and on the efforts made by the OAU, the UN and the International Community to implement the Lusaka Ceasefire Agreement. In Decision CM/Dec. 663 (LXXVI) Council had, among others, urged the Parties to the Peace Process to fulfill their obligations issuing from the Lusaka Agreement, expressed its concern about the delay in the process of the withdrawal of foreign troops, encouraged the signatories to the Lusaka Agreement to continue their contacts in order to establish the conditions conducive to its implementation, requested the United Nations to strengthen the capacity and expand the mandate of MONUC to enable it carry out successfully the tasks assigned to it in Phase III of its deployment and appealed to the International Community to continue to support the Peace Process in the DRC. -

Of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO

Assessing the of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO REPORT 3/2019 Publisher: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs Copyright: © Norwegian Institute of International Affairs 2019 ISBN: 978-82-7002-346-2 Any views expressed in this publication are those of the author. Tey should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. Te text may not be re-published in part or in full without the permission of NUPI and the authors. Visiting address: C.J. Hambros plass 2d Address: P.O. Box 8159 Dep. NO-0033 Oslo, Norway Internet: effectivepeaceops.net | www.nupi.no E-mail: [email protected] Fax: [+ 47] 22 99 40 50 Tel: [+ 47] 22 99 40 00 Assessing the Efectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC (MONUC-MONUSCO) Lead Author Dr Alexandra Novosseloff, International Peace Institute (IPI), New York and Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), Oslo Co-authors Dr Adriana Erthal Abdenur, Igarapé Institute, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Prof. Tomas Mandrup, Stellenbosch University, South Africa, and Royal Danish Defence College, Copenhagen Aaron Pangburn, Social Science Research Council (SSRC), New York Data Contributors Ryan Rappa and Paul von Chamier, Center on International Cooperation (CIC), New York University, New York EPON Series Editor Dr Cedric de Coning, NUPI External Reference Group Dr Tatiana Carayannis, SSRC, New York Lisa Sharland, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Canberra Dr Charles Hunt, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) University, Australia Adam Day, Centre for Policy Research, UN University, New York Cover photo: UN Photo/Sylvain Liechti UN Photo/ Abel Kavanagh Contents Acknowledgements 5 Acronyms 7 Executive Summary 13 Te effectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC across eight critical dimensions 14 Strategic and Operational Impact of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Constraints and Challenges of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Current Dilemmas 19 Introduction 21 Section 1. -

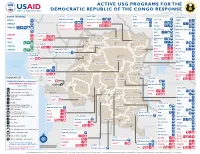

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS for the DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20 BAS-UELE HAUT-UELE ITURI S O U T H S U D A N COUNTRYWIDE NORTH KIVU OCHA IMA World Health Samaritan’s Purse AIRD Internews CARE C.A.R. Samaritan’s Purse Samaritan’s Purse IMA World Health IOM UNHAS CAMEROON DCA ACTED WFP INSO Medair FHI 360 UNICEF Samaritan’s Purse Mercy Corps IMA World Health NRC NORD-UBANGI IMC UNICEF Gbadolite Oxfam ACTED INSO NORD-UBANGI Samaritan’s WFP WFP Gemena BAS-UELE Internews HAUT-UELE Purse ICRC Buta SCF IOM SUD-UBANGI SUD-UBANGI UNHAS MONGALA Isiro Tearfund IRC WFP Lisala ACF Medair UNHCR MONGALA ITURI U Bunia Mercy Corps Mercy Corps IMA World Health G A EQUATEUR Samaritan’s NRC EQUATEUR Kisangani N Purse WFP D WFPaa Oxfam Boende A REPUBLIC OF Mbandaka TSHOPO Samaritan’s ATLANTIC NORTH GABON THE CONGO TSHUAPA Purse TSHOPO KIVU Lake OCEAN Tearfund IMA World Health Goma Victoria Inongo WHH Samaritan’s Purse RWANDA Mercy Corps BURUNDI Samaritan’s Purse MAI-NDOMBE Kindu Bukavu Samaritan’s Purse PROGRAM KEY KINSHASA SOUTH MANIEMA SANKURU MANIEMA KIVU WFP USAID/BHA Non-Food Assistance* WFP ACTED USAID/BHA Food Assistance** SA ! A IMA World Health TA N Z A N I A Kinshasa SH State/PRM KIN KASAÏ Lusambo KWILU Oxfam Kenge TANGANYIKA Agriculture and Food Security KONGO CENTRAL Kananga ACTED CRS Cash Transfers For Food Matadi LOMAMI Kalemie KASAÏ- Kabinda WFP Concern Economic Recovery and Market Tshikapa ORIENTAL Systems KWANGO Mbuji T IMA World Health KWANGO Mayi TANGANYIKA a KASAÏ- n Food Vouchers g WFP a n IMC CENTRAL y i k -

History, Archaeology and Memory of the Swahili-Arab in the Maniema

Antiquity 2020 Vol. 94 (375): e18, 1–7 https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2020.86 Project Gallery History, archaeology and memory of the Swahili-Arab in the Maniema, Democratic Republic of Congo Noemie Arazi1,*, Suzanne Bigohe2, Olivier Mulumbwa Luna3, Clément Mambu4, Igor Matonda2, Georges Senga5 & Alexandre Livingstone Smith6 1 Groundworks and Université Libre de Bruxelles, Brussels, Belgium 2 Université de Kinshasa, Kinshasa, DRC 3 Université de Lubumbashi, Lubumbashi, DRC 4 Institut des Musées Nationaux de Congo, Kinshasa, DRC 5 Picha Association, Lubumbashi, DRC 6 Royal Museum of Central Africa, Tervuren, Belgium * Author for correspondence: ✉ [email protected] A research project focused on the cultural heritage of the Swahili-Arab in the Democratic Republic of Congo has confirmed the location of their former settlement in Kasongo, one of the westernmost trading entrepôts in a network of settlements connecting Central Africa with Zanzibar. This project represents the first time arch- aeological investigations, combined with oral history and archival data, have been used to understand the Swa- hili-Arab legacy in the DRC. Keywords: DRC, Kasongo, nineteenth century, Swahili-Arab, oral history, colonialism Introduction During the nineteenth century, merchants from the coastal Swahili city-states developed a vast commercial network across Eastern Central Africa. These merchants, generally referred to as Swahili-Arab, were mainly trading in slaves and ivory destined for the Sultanate of Zan- zibar as well as the Indian Ocean trade ports (Vernet 2009). The network consisted of caravan tracks connecting Central Africa with the East African coast, and included a series of strong- holds, settlements and markets. As a result of this network, the populations of Eastern Cen- tral Africa adopted the customs of the coast such as the Swahili language, coastal dress and the practice of Islam, as well as new agricultural crops and farming techniques. -

Download File

UNICEF DRC | COVID-19 Situation Report COVID-19 Situation Report #9 29 May-10 June 2020 /Desjardins COVID-19 overview Highlights (as of 10 June 2020) 25702 • 4.4 million children have access to distance learning UNI3 confirmed thanks to partnerships with 268 radio stations and 20 TV 4,480 cases channels © UNICEF/ UNICEF’s response deaths • More than 19 million people reached with key messages 96 on how to prevent COVID-19 people 565 recovered • 29,870 calls managed by the COVID-19 Hotline • 4,338 people (including 811 children) affected by COVID-19 cases under 388 investigation and 837 frontline workers provided with psychosocial support • More than 200,000 community masks distributed 2.3% Fatality Rate 392 new samples tested UNICEF’s COVID-19 Response Kinshasa recorded 88.8% (3,980) of all confirmed cases. Other affected provinces including # of cases are: # of people reached on COVID-19 through North Kivu (35) South Kivu (89) messaging on prevention and access to 48% Ituri (2) Kongo Central (221) Haut RCCE* services Katanga (38) Kwilu (2) Kwango (1) # of people reached with critical WASH Haut Lomami (1) Tshopo (1) supplies (including hygiene items) and services 78% IPC** Equateur (1) # of children who are victims of violence, including GBV, abuse, neglect or living outside 88% DRC COVID-19 Response PSS*** of a family setting that are identified and… Funding Status # of children and women receiving essential healthcare services in UNICEF supported 34% Health facilities Funds # of caregivers of children (0-23 months) available* DRC COVID-19 reached with messages on breadstfeeding in 15% 30% Funding the context of COVID-19 requirements* : Nutrition $ 58,036,209 # of children supported with distance/home- 29% based learning Funding Education Gap 70% 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% *Funds available include 9 million USD * Risk Communication and Community Engagement UNICEF regular ressources allocated by ** Infection Prevention and Control the office for first response needs. -

Democratic Republic of Congo

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 14, No. 6 (G) – August 2002 I counted thirty bodies and bags between the dam and the small rapids, and twelve beyond the rapids. Most corpses were in underwear, and many were beheaded. On the bridges there were still many traces of blood despite attempts to cover them with sand, and on the small maize field to the left of the landing the odors were unbearable. Human Rights Watch interview, Kisangani, June 2002. A Congolese man from Kisangani covers his mouth as he nears the Tshopo bridge, the scene of summary executions by RCD-Goma troops following an attempted mutiny. (c) 2002 AFP WAR CRIMES IN KISANGANI: The Response of Rwandan-backed Rebels to the May 2002 Mutiny 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] August 2002 Vol. 14, No 6 (A) DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO WAR CRIMES IN KISANGANI: The Response of Rwandan-backed Rebels to the May 2002 Mutiny I. SUMMARY...........................................................................................................................................................2 II. RECOMMENDATIONS......................................................................................................................................3 -

Democratic Republic of Congo

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 15, No. 11 (A) - July 2003 I hid in the mountains and went back down to Songolo at about 3:00 p.m. I saw many people killed and even saw traces of blood where people had been dragged. I counted 82 bodies most of whom had been killed by bullets. We did a survey and found that 787 people were missing – we presumed they were all dead though we don’t know. Some of the bodies were in the road, others in the forest. Three people were even killed by mines. Those who attacked knew the town and posted themselves on the footpaths to kill people as they were fleeing. -- Testimony to Human Rights Watch ITURI: “COVERED IN BLOOD” Ethnically Targeted Violence In Northeastern DR Congo 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] “You cannot escape from the horror” This story of fifteen-year-old Elise is one of many in Ituri. She fled one attack after another and witnessed appalling atrocities. Walking for more than 300 miles in her search for safety, Elise survived to tell her tale; many others have not. -

The Congo War and the Prospects of State Formation Rwanda and Uganda Compared

[675] Paper The Congo war and the prospects of state formation Rwanda and Uganda compared Stein Sundstøl Eriksen No. 675 – 2005 Norwegian Institute Norsk of International Utenrikspolitisk Affairs Institutt Utgiver: NUPI Copyright: © Norsk Utenrikspolitisk Institutt 2005 ISSN: 0800 - 0018 Alle synspunkter står for forfatternes regning. De må ikke tolkes som uttrykk for oppfatninger som kan tillegges Norsk Utenrikspolitisk Institutt. Artiklene kan ikke reproduseres - helt eller delvis - ved trykking, fotokopiering eller på annen måte uten tillatelse fra forfatterne. Any views expressed in this publication are those of the author. They should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. The text may not be printed in part or in full without the permission of the author. Besøksadresse: C.J. Hambrosplass 2d Addresse: Postboks 8159 Dep. 0033 Oslo Internett: www.nupi.no E-post: [email protected] Fax: [+ 47] 22 36 21 82 Tel: [+ 47] 22 99 40 00 The Congo war and the prospects of state formation Rwanda and Uganda compared Stein Sundstøl Eriksen [Summary] This paper analyses the effect of the Congo war on state power in Rwanda and Uganda. Drawing on theories of European state formation, it asks whether the Congo war has led to a strengthening of the state in the two countries. It is argued that this has not been the case. Neither the Rwandan nor the Ugandan state has been strengthened as a result of the war. I argue that this must be explained by changes in the state system, which have altered the links between war and state formation. -

Democratic Republic of the Congo – Ebola Outbreaks SEPTEMBER 30, 2020

Fact Sheet #10 Fiscal Year (FY) 2020 Democratic Republic of the Congo – Ebola Outbreaks SEPTEMBER 30, 2020 SITUATION AT A GLANCE 128 53 13 3,470 2,287 Total Confirmed and Total EVD-Related Total EVD-Affected Total Confirmed and Total EVD-Related Probable EVD Cases in Deaths in Équateur Health Zones in Probable EVD Cases in Deaths in Eastern DRC Équateur Équateur Eastern DRC at End of at End of Outbreak Outbreak MoH – September 30, 2020 MoH – September 30, 2020 MoH – September 30, 2020 MoH – June 25, 2020 MoH – June 25, 2020 Health actors remain concerned about surveillance gaps in northwestern DRC’s Équateur Province. In recent weeks, several contacts of EVD patients have travelled undetected to neighboring RoC and the DRC’s Mai- Ndombe Province, heightening the risk of regional EVD spread. Logistics coordination in Equateur has significantly improved in recent weeks, with response actors establishing a Logistics Cluster in September. The 90-day enhanced surveillance period in eastern DRC ended on September 25. TOTAL USAID HUMANITARIAN FUNDING USAID/BHA1,2 $152,614,242 For the DRC Ebola Outbreaks Response in FY 2020 USAID/GH in $2,500,000 Neighboring Countries3 For complete funding breakdown with partners, see funding chart on page 6 Total $155,114,2424 1USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (USAID/BHA) 2 Total USAID/BHA funding includes non-food humanitarian assistance from the former Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance. 3 USAID’s Bureau for Global Health (USAID/GH) 4 Some of the USAID funding intended for Ebola virus disease (EVD)-related programs in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is now supporting EVD response activities in Équateur. -

The Kampene Gold Pilot, Maniema, DR Congo – Fact Sheet

The Kampene Gold Pilot, Maniema, DR Congo – Fact Sheet Background Artisanal and small-scale (ASM) gold mining signifi cantly contributes to the livelihood of more than 200,000 miners and their families in the Eastern Provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). ASM activities are mostly informal and supply chains are not traceable. As a result, most ASM gold is smuggled out of the country. The Kampene Gold Pilot is an on-going initiative contributing to fi nding solutions for legal ASM gold supply chains in the DRC. It forms part of a German-Congolese technical cooperation project: Since 2009, the Fe- deral Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources (BGR) has been supporting the Congolese Ministry of Mines, its technical services and mining cooperatives in improving working conditions, environmental and social standards in the ASM sector, including gold. The pilot initiative is focusing on ASM production sites around Kampene town, Maniema province. This province has signifi cantly lower confl ict risks compared to other DRC provinces. The area of Kampene is home to >10,000 ASM gold miners, organized in 9 cooperatives and operating 32 gold mine sites. The pilot initiative aims to incentivize legal and traceable gold supply chains including use of novel tracking technology. Electronic Gold Traceability • Traceability is facilitated through GPS-backed electronic registration of individual gold supply chain partici- pants and gold transactions, with automatic transmission to an online database. • The initiative integrates traceability along existing national gold supply chains from Kampene to Kindu and Bukavu, rather than creating an artificial “closed pipe”. • Tracking and tracing of ASM gold flexibly involves miners, traders, and state authorities who monitor tran- sactions.