Guidelines for the Effective Use of Uniformed Transit Police and Security Personnel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Las Vegas Monorail, an Innovative Solution for Public Transportation Problems Within the Resort Corridor

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 4-1999 The Las Vegas Monorail, an innovative solution for public transportation problems within the resort corridor Cam C. Walker University of Nevada Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Public Administration Commons Repository Citation Walker, Cam C., "The Las Vegas Monorail, an innovative solution for public transportation problems within the resort corridor" (1999). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 198. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/1439111 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Monorail 1 THE LAS VEGAS MONORAIL, AN INNOVATIVE SOLUTION The Las Vegas Monorail: An Innovative Solution for Public Transportation Problems within the Resort Corridor By Cam C. Walker Bachelor of Science Brigham Young -

Southern California Rapid Transit District (SCRTD)

Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority Law ---------------------------------------------------------------------- With corresponding provisions of the Southern California Rapid Transit District Law and Los Angeles County Transportation Commission Law Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority California Public Utilities Code Page 2 of 110 Introduction The Southern California Rapid Transit District, also known as the SCRTD or the “District” (1964-1993) was created by the State as the successor to the Los Angeles Metropolitan Transit Authority or “LAMTA” (1958-1964). LAMTA was the first publicly governed transit operator in Los Angeles and also responsible for the planning of a new mass transit system to replace the aging remnants of the transit systems built by Pacific Electric (1899-1953) and Los Angeles Railway (1895-1945). Unfortunately, the LAMTA had no ability to raise tax revenues or powers of eminent domain, and its board was appointed by the Governor, making the task building local support for mass transit improvements difficult at best. Dissatisfaction with the underpowered LAMTA led to a complete re-write of its legislative authority. While referred to in state legislation as a merger, the District law completely overwrote the LAMTA Act of 1957. The Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, also known as LACTC or the “Commission” (1977-1993) was created by the State in 1976 as a separate countywide transportation planning agency, along with transportation commissions in San Bernardino, Riverside, and Orange counties. At the time the District was initially created, there were no transit or transportation grant programs available from the State or Federal governments. Once funding sources became available from the Urban Mass Transit Administration, now the Federal Transit Administration, the California Transportation Commission, and others, the creation of county transportation commissions ensured coordination of multimodal transportation planning and funding programs. -

Metro Rail Moves Forward; Concept to Become Reality

Metro Rail Moves Forward; Concept to Become Reality COUNCIL GRANTS EXTENSION additional funds for expenses involved ON EIR . METRO RAIL BENEFIT in relocating and rearranging Santa ASSESSMENT DISTRICTS . JUDGE Fe's track and facilities. QUESTIONS METRO RAIL REPORT Most news stories lately have been . RTD SCHEDULES PUBLIC HEAR- an funding. As Headway goes to INGS ON METRO RAIL . SALES- press, the District is awaiting word TAX FUNDS EARMARKED FOR MET- from Washington an whether Con- RO RAIL SUBWAY . NEW STUDY gress will commit construction funds SOUGHT ON IMPACT OF METRO to the project in the form of a "Letter of RAIL . METRO RAIL BUILDERS Intent," the last remaining step before TRIM REQUEST FOR FEDERAL letting of construction contracts. FUNDING ... METRO RAIL GETS "We finally have our act together FUNDS . COMMISSION ALLO- here in Los Angeles," RTD President CATES $406 MILLION TOWARD MET- Nick Patsaouras said following a mid- RO RAIL CONSTRUCTION . September approval by the Los Angeles City Council of a first-year These are just a few of the terms commitment of $7 million to Metro Rail each of us see and hear virtually every- as part of an overall $69 million city day an the District's Metro Rail subway share. "Previously when we tried to get project. federel funding, they have always told Don't feel alone if you are somewhat us to go back home and arrive at a overwhelmed by the terms and rhetor- local consensus and funding ic. Even some District staff members package." who work full time an Metro Rail have difficulty keeping up with all the de- Prop. -

Los Angeles Transportation Transit History – South LA

Los Angeles Transportation Transit History – South LA Matthew Barrett Metro Transportation Research Library, Archive & Public Records - metro.net/library Transportation Research Library & Archive • Originally the library of the Los • Transportation research library for Angeles Railway (1895-1945), employees, consultants, students, and intended to serve as both academics, other government public outreach and an agencies and the general public. employee resource. • Partner of the National • Repository of federally funded Transportation Library, member of transportation research starting Transportation Knowledge in 1971. Networks, and affiliate of the National Academies’ Transportation • Began computer cataloging into Research Board (TRB). OCLC’s World Catalog using Library of Congress Subject • Largest transit operator-owned Headings and honoring library, forth largest transportation interlibrary loan requests from library collection after U.C. outside institutions in 1978. Berkeley, Northwestern University and the U.S. DOT’s Volpe Center. • Archive of Los Angeles transit history from 1873-present. • Member of Getty/USC’s L.A. as Subject forum. Accessing the Library • Online: metro.net/library – Library Catalog librarycat.metro.net – Daily aggregated transportation news headlines: headlines.metroprimaryresources.info – Highlights of current and historical documents in our collection: metroprimaryresources.info – Photos: flickr.com/metrolibraryarchive – Film/Video: youtube/metrolibrarian – Social Media: facebook, twitter, tumblr, google+, -

Gao-13-20, Passenger Rail Security

United States Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Committees GAO December 2012 PASSENGER RAIL SECURITY Consistent Incident Reporting and Analysis Needed to Achieve Program Objectives GAO-13-20 December 2012 PASSENGER RAIL SECURITY Consistent Incident Reporting and Analysis Needed to Achieve Program Objectives Highlights of GAO-13-20, a report to congressional committees Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found Terrorist attacks on foreign passenger The Transportation Security Administration (TSA) has inconsistently overseen rail systems, which include rail transit and enforced its rail security incident reporting requirement because it does not and intercity rail, have underscored the have guidance and its oversight mechanisms are limited, leading to considerable importance of collecting and analyzing variation in the types and number of incidents reported. Though some variation is security incident information to identify expected in the number and type of incidents reported because of differences in potential vulnerabilities. Within the rail agency size, location, and ridership, local TSA inspection officials have federal government, TSA is the primary provided rail agencies with inconsistent interpretations of the reporting agency responsible for overseeing and requirement. For example, local TSA officials instructed one rail agency to report enhancing passenger rail security, and all incidents related to individuals struck by trains. However, local TSA officials has several programs to fulfill this responsible for another rail agency said these incidents would not need to be responsibility. In 2008, TSA issued a regulation requiring U.S. passenger rail reported as they are most often suicides with no nexus to terrorism. Providing agencies to report all potential threats guidance to local TSA inspection officials and rail agencies on the types of and significant security concerns to incidents that are to be reported could improve consistency across different TSA TSA, among other things. -

Connecticut Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Paratransit Application Form

CT_ADAApplication_Rev8_12-19 Connecticut Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Paratransit Application Form Instructions for Submission To request a copy of this application in an accessible format, please call (203) 365- 8522 Extension 2061. The purpose of this application is to determine eligibility for Connecticut complementary ADA Paratransit service. If you have a disability that prevent s you from using the public transit bus service in Connecticut, you may be eligible for ADA Paratransit service. ADA Paratransit is a shared ride, advanced reservation, origin-to-destination service for persons with disabilities who are unable to use the public bus service because of their disability. Service Criteria The Connecticut ADA Paratransit program is designed to meet the Americans with Disabilities Act service criteria established by the federal government. Service is provided only to individuals f ound eligible by a Connecticut regional ADA service provider and is operated under the following ADA guidelines: • Complementary service is only provided in areas where public buses operate. This does not include Express Commuter service, Intercity or Dial-A-Ride services. ADA Paratransit vehicles can only make pick-ups and drop-offs at places that are within three-quarters of a mile of a public bus route. • Service is provided only during the hours and days when public bus service in that area operates. • Rides must be reserved at least one day inadvance. • ADA Paratransit fares are typically double the cost of a full fare on a public bus route. • Service is not restricted by trip purpose but provided for all types of trips. ADA Definition of Disability Any person with a disability who is unable, as a result of a physical or mental impairment, and without the assistance of another individual (except the operator of a wheelchair lift), to board, ride, or disembark from any public bus. -

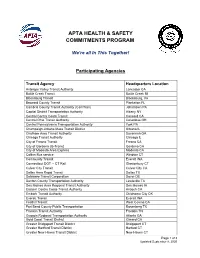

Apta Health & Safety Commitments Program

APTA HEALTH & SAFETY COMMITMENTS PROGRAM We’re all In This Together! Participating Agencies Transit Agency Headquarters Location Antelope Valley Transit Authority Lancaster CA Battle Creek Transit Battle Creek MI Blacksburg Transit Blacksburg, VA Broward County Transit Plantation FL Cambria County Transit Authority (CamTran) Johnstown PA Capital District Transportation Authority Albany NY Central Contra Costa Transit Concord CA Central Ohio Transit Authority Columbus OH Central Pennsylvania Transportation Authority York PA Champaign-Urbana Mass Transit District Urbana IL Chatham Area Transit Authority Savannah GA Chicago Transit Authority Chicago IL City of Fresno Transit Fresno CA City of Gardena (G-Trans) Gardena CA City of Modesto Area Express Modesto CA Collins Bus service Windsor CT Community Transit Everett WA Connecticut DOT -- CT Rail Glastonbury CT Culver City Transit Culver City CA Dallas Area Rapid Transit Dallas TX Delaware Transit Corporation Dover DE Denton County Transportation Authority Lewisville TX Des Moines Area Regional Transit Authority Des Moines IA Eastern Contra Costa Transit Authority Antioch CA Embark Transit Authority Oklahoma City OK Everett Transit Everett WA Foothill Transit West Covina CA Fort Bend County Public Transportation Rosenberg TX Franklin Transit Authority Franklin TN Georgia Regional Transportation Authority Atlanta GA Gold Coast Transit District Oxnard CA Greater Bridgeport Transit District Bridgeport CT Greater Hartford Transit District Harford CT Greater New Haven Transit District New Haven -

ADA Paratransit Application.Rev 08

____________________________________________________________ Accessible Services 1221 R Street Sacramento, CA 95811 PHONE: 916-557-4685 or 916-557-4686 (TDD) FAX: 916-455-3924 [email protected] www.sacrt.com/accessibleservices.stm Thank you for inquiring about eligibility for ADA Paratransit Service. Sacramento Regional Transit’s Paratransit Service is a “Safety Net” for people with physical, cognitive or visual disabilities that are functionally unable to independently use the RT fixed route service either all of the time, temporarily or only under certain circumstances. Enclosed are the ADA Paratransit Application and Eligibility Brochure that explains ADA Paratransit Service. Please read the Eligibility Brochure carefully before completing your application. The Steps in the Eligibility Process 1. Request the application packet. 2. Read the Eligibility Brochure that is enclosed. 3. Complete all questions on the Paratransit Application that follows this page. 4. Submit your application to your physician, or other professional, to complete the professional verification section. 5. Mail your signed and completed application and professional verification form to: Sacramento Regional Transit District, Accessible Services PO Box 2110 Sacramento, CA 95812-2110 6. You may be asked to attend an in-person interview. Your eligibility will be determined within 21 days from the date you complete your telephone and/or in- person interview and functional assessment. You will be notified by letter as to your eligibility status. 7. If you do not receive written notice of RT’s decision within 21 days, you may request paratransit services until a decision has been made by calling (916) 557-4685 or (916) 557-4686 (TDD). An incomplete application will be returned and will delay processing. -

Metro Transit Police Department

Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority Metro Transit Police Department Chief Michael A. Taborn August 2012 Metro Transit Police Department Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) is a critical national asset. WMATA transports more than 40% of Federal Government employees to and from work during peak ridership hours MTPD Overview • 492 Sworn Officers, 164 Special Police Officers, 53 Civilians • Jurisdiction and arrest powers throughout the 1,500 square mile transit zone • Six MTPD Bureaus: o Executive Office of the Chief o Administrative Services Bureau o Office of Emergency Management o Patrol Operations Bureau o Special Operations Bureau o Homeland Security, Investigations and Intelligence Bureau Highlights 2011 – January - December • 16% reduction in Part I Crimes • 1,922 arrests • 7,020 criminal/civil citations for fare evasion and public conduct violations • 27% reduction in bus operator assaults (Reduced 90 to 66 assaults) • The probability of being a victim of a Part I crime in the Metrorail system is 5.61 per million riders X X X x MTPD Identified Crime Trends • Robberies and Larcenies • Assess crime trends through MetroStat to manage the deployment of officers • Mobilize Anti-Terrorism Teams(ATT) to blend patrol strategies with crime prevention goals • Increase the use of casual clothes officers to combat robberies and larcenies • Educate customers through a strong public awareness campaign • Youth disorder • Partner with local law enforcement agencies and strategize common crime prevention goals • High visible uniform presence in stations and parking lots MTPD Part I Crime Report 5 Year Comparison – Annual Part I Crime 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Aggravated Assault 106 92 94 136 108 Burglary 5 2 0 5 1 Homicide *1 0 *1 *1 *1 Larceny 739 864 811 925 791 Motor Vehicle Theft 166 181 152 129 83 Attempt Motor Vehicle Theft 117 101 79 65 43 Rape/Sexual Offenses 1 0 1 3 1 Robbery 445 581 894 1,007 871 Total 1,580 1,821 2,032 2,270 1,898 * Homicides reported and investigated by other police agencies. -

Norwalk Transit District Paratransit Services – Riders Guide

Norwalk Transit District Paratransit Services – Riders Guide Introduction Paratransit transportation services consist of a variety of door to door service for the elderly and/or person with disabilities. All paratransit services are a shared ride service. It is not emergency medical transportation nor is it a personal taxi service. To ensure the greatest level of operating and cost efficiency you should expect to be traveling with other riders who are going in the same direction as yourself. Each service has its own rules of operation including service area and hours of operation. Please review each section below, for the program that you are eligible to travel under for specific program requirements. Service Areas Dispatch-A-Ride / Norwalk ADA – is available for travel within a ¾ mile radius of a Norwalk Transit bus route within Norwalk, during the same hours that the route operates. Service outside this ¾ mile area in Norwalk is not provided. This service is available to anyone with a disability and/or impairment that prevents them from using a city bus. Easy Access / Stamford ADA - is available for travel within the city of Stamford and within ¾ mile radius of an operating CT Transit bus route within Greenwich, Darien, Norwalk and limited areas of New York, during the same hours that the route operates. Service outside this ¾ mile area in New York, Greenwich and Darien is not provided. This service is available to anyone with a disability and/or impairment that prevents them from using a city bus. Westport Elderly & Disabled / Town of Westport – is available for travel within the Town of Westport to anyone 65 years of age and older, or 64 years of age and younger that has a disability and/or impairment. -

Bus Transit Subsidies in Connecticut

84 TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH RECORD 1202 Abridgment Bus Transit Subsidies in Connecticut HERBERT S. LEVINSON This paper traces the development of state transit operating 120-day strike in November 1972 in the three areas led to subsidies in Connecticut and analyzes various operating sub resumption of service on March 26, 1973, with a two-year sidy options. From these analysis, an efficiency incentive for state guarantee of operating deficits. The state required that mula was recommended to the Connecticut Public Transpor transit districts be formed within two years. Threatened again tation Commission in 1985. Under this formula, the state's with service discontinuance, the state purchased the assets of share of operating costs increased as the farebox recovery ratio the Connecticut Company on May 26, 1976, using Federal increased. Because this approach would increase state aid to Section 3 funds to cover 80 percent of the capital cost it some independent transit districts and reduce it to others, it established. Connecticut Transit was established to provide was not acceptable to the state legislature. A revised "constant bus service in the three cities. state share" formula, in which the state pays the operating The decision to establish Connecticut Transit statewide deficit up to 67 percent of the total operating costs subsequently was implemented by the state Department of Transportation reflected both the need for the state to act quickly, and the and legislature. apparent inability or unwillingness of the major cities to act (including some perceptions of extensive urban-to-rural sub This paper traces the development of state transit operating sidies in other sectors of the economy). -

Perspectives on Transit Security in the 1990S: Strategies for Success TT654/U6117

NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. NOTICE The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers' names appear hereir solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302 and to the Office of Management and Budget, .Paperwork Reduction Project ( 0704-0188) . Washington. DC 26503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED June 1996 Final Report January 1995 - April 1996 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Perspectives on Transit Security in the 1990s: Strategies for Success TT654/U6117 6. AUTHOR(S) M. Annabelle Boyd, M. Patricia Maier, Patricia J. Kenney 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8.PERFORMING ORGANIZATION Boyd, Maier & Associates REPORT NUMBER Route 2, Box 242 DOT-VNTSC-FTA-96-2 Barboursville, VA 22923 9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. SPONSORING/MONITORING U.S. Department of Transportation AGENCY REPORT NUMBER Federal Transit Administration Office of Program Management, Office of Safety and Security FTA-MA-90-7006-96-1 Washington, DC 20590 11.