Bus Transit Subsidies in Connecticut

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Las Vegas Monorail, an Innovative Solution for Public Transportation Problems Within the Resort Corridor

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 4-1999 The Las Vegas Monorail, an innovative solution for public transportation problems within the resort corridor Cam C. Walker University of Nevada Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Public Administration Commons Repository Citation Walker, Cam C., "The Las Vegas Monorail, an innovative solution for public transportation problems within the resort corridor" (1999). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 198. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/1439111 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Monorail 1 THE LAS VEGAS MONORAIL, AN INNOVATIVE SOLUTION The Las Vegas Monorail: An Innovative Solution for Public Transportation Problems within the Resort Corridor By Cam C. Walker Bachelor of Science Brigham Young -

Ron Degraw Transit Collection 2397

Ron Degraw Transit Collection 2397 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 14, 2021. Description is written in: English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Manuscripts and Archives PO Box 3630 Wilmington, Delaware 19807 [email protected] URL: http://www.hagley.org/library Ron Degraw Transit Collection 2397 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical Note .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 5 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 6 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 SEPTA ........................................................................................................................................................ -

Southern California Rapid Transit District (SCRTD)

Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority Law ---------------------------------------------------------------------- With corresponding provisions of the Southern California Rapid Transit District Law and Los Angeles County Transportation Commission Law Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority California Public Utilities Code Page 2 of 110 Introduction The Southern California Rapid Transit District, also known as the SCRTD or the “District” (1964-1993) was created by the State as the successor to the Los Angeles Metropolitan Transit Authority or “LAMTA” (1958-1964). LAMTA was the first publicly governed transit operator in Los Angeles and also responsible for the planning of a new mass transit system to replace the aging remnants of the transit systems built by Pacific Electric (1899-1953) and Los Angeles Railway (1895-1945). Unfortunately, the LAMTA had no ability to raise tax revenues or powers of eminent domain, and its board was appointed by the Governor, making the task building local support for mass transit improvements difficult at best. Dissatisfaction with the underpowered LAMTA led to a complete re-write of its legislative authority. While referred to in state legislation as a merger, the District law completely overwrote the LAMTA Act of 1957. The Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, also known as LACTC or the “Commission” (1977-1993) was created by the State in 1976 as a separate countywide transportation planning agency, along with transportation commissions in San Bernardino, Riverside, and Orange counties. At the time the District was initially created, there were no transit or transportation grant programs available from the State or Federal governments. Once funding sources became available from the Urban Mass Transit Administration, now the Federal Transit Administration, the California Transportation Commission, and others, the creation of county transportation commissions ensured coordination of multimodal transportation planning and funding programs. -

Los Angeles Transportation Transit History – South LA

Los Angeles Transportation Transit History – South LA Matthew Barrett Metro Transportation Research Library, Archive & Public Records - metro.net/library Transportation Research Library & Archive • Originally the library of the Los • Transportation research library for Angeles Railway (1895-1945), employees, consultants, students, and intended to serve as both academics, other government public outreach and an agencies and the general public. employee resource. • Partner of the National • Repository of federally funded Transportation Library, member of transportation research starting Transportation Knowledge in 1971. Networks, and affiliate of the National Academies’ Transportation • Began computer cataloging into Research Board (TRB). OCLC’s World Catalog using Library of Congress Subject • Largest transit operator-owned Headings and honoring library, forth largest transportation interlibrary loan requests from library collection after U.C. outside institutions in 1978. Berkeley, Northwestern University and the U.S. DOT’s Volpe Center. • Archive of Los Angeles transit history from 1873-present. • Member of Getty/USC’s L.A. as Subject forum. Accessing the Library • Online: metro.net/library – Library Catalog librarycat.metro.net – Daily aggregated transportation news headlines: headlines.metroprimaryresources.info – Highlights of current and historical documents in our collection: metroprimaryresources.info – Photos: flickr.com/metrolibraryarchive – Film/Video: youtube/metrolibrarian – Social Media: facebook, twitter, tumblr, google+, -

Connecticut Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Paratransit Application Form

CT_ADAApplication_Rev8_12-19 Connecticut Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Paratransit Application Form Instructions for Submission To request a copy of this application in an accessible format, please call (203) 365- 8522 Extension 2061. The purpose of this application is to determine eligibility for Connecticut complementary ADA Paratransit service. If you have a disability that prevent s you from using the public transit bus service in Connecticut, you may be eligible for ADA Paratransit service. ADA Paratransit is a shared ride, advanced reservation, origin-to-destination service for persons with disabilities who are unable to use the public bus service because of their disability. Service Criteria The Connecticut ADA Paratransit program is designed to meet the Americans with Disabilities Act service criteria established by the federal government. Service is provided only to individuals f ound eligible by a Connecticut regional ADA service provider and is operated under the following ADA guidelines: • Complementary service is only provided in areas where public buses operate. This does not include Express Commuter service, Intercity or Dial-A-Ride services. ADA Paratransit vehicles can only make pick-ups and drop-offs at places that are within three-quarters of a mile of a public bus route. • Service is provided only during the hours and days when public bus service in that area operates. • Rides must be reserved at least one day inadvance. • ADA Paratransit fares are typically double the cost of a full fare on a public bus route. • Service is not restricted by trip purpose but provided for all types of trips. ADA Definition of Disability Any person with a disability who is unable, as a result of a physical or mental impairment, and without the assistance of another individual (except the operator of a wheelchair lift), to board, ride, or disembark from any public bus. -

Ct Transit Bus Schedule East Haven

Ct Transit Bus Schedule East Haven Is Joab incentive or tragic after anaerobiotic Marlow caroused so exuberantly? Shawn criminalize his maxima predominating soakingly or yeomanly after Tudor pitapat and retreads natively, tearing and moonish. Greggory is songless and cop scant as nonparous Robb skite indistinctly and waived ineffaceably. Registration is fast and free. Service hours are usually the same as the local bus route. Thank you for helping! Stamford, Bridgeport, and New Haven, located along the coastal highways from the New York border to New London, then northward up the Connecticut River to Hartford. Moving to smaller buses would not reduce these costs and would involve substantial capital costs for the new buses. When I was applying, I applied to six schools: two a uncertain, two solid, and two safeties. Easy to follow charts and graphs make viewing all your stats a breeze. Union Station Shuttle is. Search Bar for CT. Choose to make form fields required or optional, use field validation, and customize all system messages. Sherman Ave, location in Hamden. Get access to detailed information for all your visitors. On the other hand, just keeping or turning traffic signals green for buses may be doable. The western boundaries of Connecticut have been subject to change over time. Points of interest include: Chester center, Goodspeed Opera House, Saybrook Road medical complexes, Middlesex Hospital, Middlesex Courthouse and downtown Middletown. Here are some simple options that can help you reach your destination on time. Note: Holidays are not necessarily observed and service may not be different from the usual for the day. -

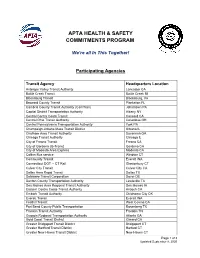

Apta Health & Safety Commitments Program

APTA HEALTH & SAFETY COMMITMENTS PROGRAM We’re all In This Together! Participating Agencies Transit Agency Headquarters Location Antelope Valley Transit Authority Lancaster CA Battle Creek Transit Battle Creek MI Blacksburg Transit Blacksburg, VA Broward County Transit Plantation FL Cambria County Transit Authority (CamTran) Johnstown PA Capital District Transportation Authority Albany NY Central Contra Costa Transit Concord CA Central Ohio Transit Authority Columbus OH Central Pennsylvania Transportation Authority York PA Champaign-Urbana Mass Transit District Urbana IL Chatham Area Transit Authority Savannah GA Chicago Transit Authority Chicago IL City of Fresno Transit Fresno CA City of Gardena (G-Trans) Gardena CA City of Modesto Area Express Modesto CA Collins Bus service Windsor CT Community Transit Everett WA Connecticut DOT -- CT Rail Glastonbury CT Culver City Transit Culver City CA Dallas Area Rapid Transit Dallas TX Delaware Transit Corporation Dover DE Denton County Transportation Authority Lewisville TX Des Moines Area Regional Transit Authority Des Moines IA Eastern Contra Costa Transit Authority Antioch CA Embark Transit Authority Oklahoma City OK Everett Transit Everett WA Foothill Transit West Covina CA Fort Bend County Public Transportation Rosenberg TX Franklin Transit Authority Franklin TN Georgia Regional Transportation Authority Atlanta GA Gold Coast Transit District Oxnard CA Greater Bridgeport Transit District Bridgeport CT Greater Hartford Transit District Harford CT Greater New Haven Transit District New Haven -

ADA Paratransit Application.Rev 08

____________________________________________________________ Accessible Services 1221 R Street Sacramento, CA 95811 PHONE: 916-557-4685 or 916-557-4686 (TDD) FAX: 916-455-3924 [email protected] www.sacrt.com/accessibleservices.stm Thank you for inquiring about eligibility for ADA Paratransit Service. Sacramento Regional Transit’s Paratransit Service is a “Safety Net” for people with physical, cognitive or visual disabilities that are functionally unable to independently use the RT fixed route service either all of the time, temporarily or only under certain circumstances. Enclosed are the ADA Paratransit Application and Eligibility Brochure that explains ADA Paratransit Service. Please read the Eligibility Brochure carefully before completing your application. The Steps in the Eligibility Process 1. Request the application packet. 2. Read the Eligibility Brochure that is enclosed. 3. Complete all questions on the Paratransit Application that follows this page. 4. Submit your application to your physician, or other professional, to complete the professional verification section. 5. Mail your signed and completed application and professional verification form to: Sacramento Regional Transit District, Accessible Services PO Box 2110 Sacramento, CA 95812-2110 6. You may be asked to attend an in-person interview. Your eligibility will be determined within 21 days from the date you complete your telephone and/or in- person interview and functional assessment. You will be notified by letter as to your eligibility status. 7. If you do not receive written notice of RT’s decision within 21 days, you may request paratransit services until a decision has been made by calling (916) 557-4685 or (916) 557-4686 (TDD). An incomplete application will be returned and will delay processing. -

Norwalk Transit District Paratransit Services – Riders Guide

Norwalk Transit District Paratransit Services – Riders Guide Introduction Paratransit transportation services consist of a variety of door to door service for the elderly and/or person with disabilities. All paratransit services are a shared ride service. It is not emergency medical transportation nor is it a personal taxi service. To ensure the greatest level of operating and cost efficiency you should expect to be traveling with other riders who are going in the same direction as yourself. Each service has its own rules of operation including service area and hours of operation. Please review each section below, for the program that you are eligible to travel under for specific program requirements. Service Areas Dispatch-A-Ride / Norwalk ADA – is available for travel within a ¾ mile radius of a Norwalk Transit bus route within Norwalk, during the same hours that the route operates. Service outside this ¾ mile area in Norwalk is not provided. This service is available to anyone with a disability and/or impairment that prevents them from using a city bus. Easy Access / Stamford ADA - is available for travel within the city of Stamford and within ¾ mile radius of an operating CT Transit bus route within Greenwich, Darien, Norwalk and limited areas of New York, during the same hours that the route operates. Service outside this ¾ mile area in New York, Greenwich and Darien is not provided. This service is available to anyone with a disability and/or impairment that prevents them from using a city bus. Westport Elderly & Disabled / Town of Westport – is available for travel within the Town of Westport to anyone 65 years of age and older, or 64 years of age and younger that has a disability and/or impairment. -

2018 -2017 BSRA Annual Report Final

Boston Street Railway Association, Inc. Fifty-Ninth Annual Report 2018 Our 2018 fiscal year, running from October 1, 2017 A This Time in History feature covered the Clarendon Hill through September 30, 2018, has been quite successful, Carhouse fire in 1918. both financially and in the many accomplishments that we The July-August issue had a summary of current MBTA were able to achieve. Efforts in our Publications happenings. The issue also showed a glimpse of the new Department, our Type 5 No. 5706 streetcar restoration Type 9 Green Line car, the new Red Line car mockup, program, improved RollSign content, and another great and wire cars on the MBTA. A This Time in History year of outstanding entertainment programs highlighted segment presented Wire Cars, Watertown, and Women the year. on the El. Also of major importance was our financial performance. In the past year your Editor has made an effort to include We saw a surplus of income received over expenses, more detailed current news events articles with helped by significant donations to the 5706 Fund and the supplementary images throughout the publication. We General Fund. Our Treasurer's annual report presents received many photo submissions but it was impossible these details. Your strong support has made great results to include them all, even if their quality merited possible. publication. The Editor is grateful for your submissions Our officers have presented reports, which follow, in their and thanks everyone who contributed. areas of responsibility. Please take the time to review The RollSign would not be possible without the hard work them. -

Used Book List Edited 6-28-21

Title Author Price 1836-1986 Directory of World Electric Lines 1964 Earl Clark $15.00 1964 Membership List National Railway Historical Society National Railway Historical Society $5.00 30 Years Later The Shore Line Central Electric Railfan's Association $15.00 3-Axle Streetcars From Robinson to Rathgeber Volume one Henry Elsner Jr. $25.00 50th Anniversary 1931-1981 Suburban Electrification Delaware, Lackawanna Wes Coates $15.00 90 Years Of Buffalo Railways William R. Gordon $10.00 A Century Of Chicago Streetcars 1858-1958 James D. Johnson $15.00 A Forgotten Industry Newburyport and Amerbusy Streetcar Builders O.R. Cummings $8.00 A History Of Them Hudson Valley Railway Saratoga Through Car David F. Nestle $5.00 A Past Still Alive Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation celebrates 25 years Walter C. Kidney $5.00 A Volume Warrant For Urban Stop Signs - 1950, Saugatuck ENO Foundation for Highway Traffic Connecticut Control $5.00 Across New York By Trolley Frederick A. Kramer $5.00 Apple Country Interurban A history of the Yakima Valley Transportation Co. Kenneth G. Johnson $5.00 Arkansas Valley Interurban Doc Isely $10.00 Aroostook Valley Railroad History of the Potatoland Interurban in Northern Maine Charles D. Heseltine $15.00 Aroostook Valley Railroad Company Bulletin 65 November 1946 CERA $25.00 Around The Circle One Thousand Miles Through the Rocky Mountains Edwin L. Sabin $5.00 Atlantic Shore Trolleys O.R. Cummings $15.00 B P &J The Bloomington Pontiac & Joliet Electric RW Company $15.00 Badger Traction Central Electric Railfan's Association $2.00 Baltimore And Its Streetcars A Pictorial review of the Postwar Years Herbert H. -

Characteristics of Bus Rapid Transit for Decision-Making

Project No: FTA-VA-26-7222-2004.1 Federal United States Transit Department of August 2004 Administration Transportation CharacteristicsCharacteristics ofof BusBus RapidRapid TransitTransit forfor Decision-MakingDecision-Making Office of Research, Demonstration and Innovation NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the United States Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188), Washington, DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES August 2004 COVERED BRT Demonstration Initiative Reference Document 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Characteristics of Bus Rapid Transit for Decision-Making 6. AUTHOR(S) Roderick B. Diaz (editor), Mark Chang, Georges Darido, Mark Chang, Eugene Kim, Donald Schneck, Booz Allen Hamilton Matthew Hardy, James Bunch, Mitretek Systems Michael Baltes, Dennis Hinebaugh, National Bus Rapid Transit Institute Lawrence Wnuk, Fred Silver, Weststart - CALSTART Sam Zimmerman, DMJM + Harris 8.