Project Filter Sponsorships

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BOISE's 0-87004-356-0 I ""~~·...; I Tion in Operating Expenses for Some Units

Bronco Athletic Association MasterCard®, you con- tribute to Bronco Athletics each time you make a purchase with your card . • One percent of each sale and 50% of the annual fee is donated to help fund scholarships for BSU student athletes. Since its inception, this program has generated over $60,000. • Don't wait! Apply for your Bronco Athletic Association MasterCard today: Applications are available thr.ough the BAA, 1910 University Dr., Boise, ID 83725, (208) 385-3556. Jf'EST()NE ~' BANK Member FDIC 0 p E N I N G D 0 0 R s V.ion is the ability to see a door when others only see a wall. Risk is grasping the handle and venturing through. Together, vision and risk define entrepreneurial spirit. From one man's vision in the 1920's to a world agribusiness leader for the 1990's, the J.R Simplot Company continues to move forward by crossing thresholds to quality, technology, product innovation, and global trade. And Simplot is meeting the challenges of growth while ensuring a clean and healthy environment. The opponunities to serve a changing world are infinite. And true to its entrepreneurial tradition, the J.R Simplot Company is opening these doors to the future, today. Bringing Earth's Resources to Life a a a BOISE STATE UNIVERSITY VOL. XIX, NO. 1 FALL 1 993 FEATURES RIVER RIDE 20 Down the Boise River with historian Susan Stacy. GREENBELT BOUND 26 Book tells story of Boise River history. EAGU ESSENTIALS 27 Researchers seek limits to acceptable change on the river. ROILING ON THE RIVER 28 BSU scientists study Boise River water quality. -

Memorial Service Book

MEMORIAL SERVICE IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF IDAHO March 2, 2021 Boise, Idaho ___________________________________________ JUDGES RESIDENCE CITY DECEASED Hon. Vern Herzog, Jr. Pocatello January 1, 2020 Hon. Edward Lewis Scott Malad February 11, 2020 Hon. Daniel Burnham Meehl Twin Falls February 24, 2020 Hon. Mildred McClure Dubois June 19, 2020 Hon. Thomas Rhea Cushman Gooding September 2, 2020 ATTORNEYS RESIDENCE CITY DECEASED David Minert Meridian August 17, 2019 Larry Dean Scott Boise March 3, 2020 William Ray Hollifield Eagle March 13, 2020 Phillip Mark Barber Boise March 26, 2020 Joseph S. (Joe) Munson Boise April 2, 2020 Peter Kent Church Burley April 6, 2020 Joseph F. Brown Meridian April 7, 2020 Jay McKenzie Preston April 26, 2020 Marc Weinpel Idaho Falls May 7, 2020 Michael Glenn Morfitt Boise May 28, 2020 Carol Lynn Brassey Boise June1, 2020 David Hamilton Twin Falls June 6, 2020 Richard Raymond Clarkson Meridian July 16, 2020 Edward Joseph Anson Pinehurst August 11, 2020 John Doerr Twin Falls August 22, 2020 Anthony De Giulio Pingree August 24, 2020 Daniel L. Spickler Lewiston September 12, 2020 Larry Kuznetz Spokane, WA September 22, 2020 Dwain Hilliard Stufflebeam Blackfoot September 28, 2020 Richard E. Hall Boise October 6, 2020 Narrvel Elwin Hall Malad October 9, 2020 Roger Darwin Ling Rupert November 8, 2020 Arthur Anderson Jr. Brighton, CO December 17, 2020 Melvin Dean Buffington Meridian December 21, 2020 JUDGES RESOLUTIONS IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF IDAHO A Resolution in Memory of HONORABLE VERN E. HERZOG, JR., DECEASED 1933-2020 RETIRED JUDGE-SHOSHONE-BANNOCK TRIBES MOTION IN MEMORIAL TO THE HONORABLE JUSTICES OF THE SUPREME COURT OF THE ST ATE OF IDAHO The undersigned a member of the Memorial Service Committee appointed by this Court, respectfully submits the following resolution: WHEREAS, with this Special Memorial Resolution, We gratefully acknowledge Vern E. -

2017-Visitor-Guide.Pdf

Play Fair Guest Services Inside info to get your Fair on. The Fairgrounds Expo Idaho is nicknamed “the fairgrounds” because— Admit Fun since 1967—it’s marked the A free ride from the Register your kids at the Tickets: spot for the Western Idaho parking lot: RMT Found Kids Booth inside the Fair. One of the biggest Equipment Tram. Guest Services area near draws around Southwest the Main Gate. Wristband ID Idaho, this is the social Information Booths – tracks kids quickly. Ages 5 & Under ................... FREE event of the summer that Outside Main Gate; brings in about 250,000 Ages 6-11 .................................... $6 i Fountain. *Wheelchairs Guest Services – Inside people every year. (Not to and strollers not available GS Main Gate, check in here Ages 12-61 .................................. $9 mention a pretty fair number for rent. for assistance, lost and of farm animals.) Beyond our Ages 62+ .....................................$7 found, sheriff’s officers. 120 year Fair legacy, there’s Medical – West end of Opening Day ... FREE Admission more here than meets the Small Animal Building – eye. Throughout the rest for serious emergencies Babies Rest Stop – Noon-2pm Noon to 9 PM – Stop in of the year, over 750,000 dial 911. Take advantage to change a diaper or people stop by for trade of the FREE sidewalk CPR nurse; air conditioned. shows, company gatherings, training. Closing Day ........Armed Service events, livestock round-ups, and everything else under Members FREE – Only ADA Access Locations – the Idaho sun. More at Service Animals animals with proper service Available throughout Family Day Promo .................$29 ExpoIdaho.com. grounds. -

Caribou - Targhee National Forest 1405 Hollipark Drive Idaho Falls, Idaho 83401 Caribou - Targhee National Forest Forest Plan Monitoring and Evaluation Report

Targhee Monitoring Report: 1997-2004 May 2006 USDA Forest Service Intermountain Region Caribou - Targhee National Forest 1405 Hollipark Drive Idaho Falls, Idaho 83401 Caribou - Targhee National Forest Forest Plan Monitoring and Evaluation Report Section 2--Accomplishment of Goals and Objectives i Targhee Monitoring Report: 1997-2004 May 2006 Accomplishment of Objectives—Summary Table Table 1: Summary of the percent of each objective that the Targhee has accomplished. Details of how each objective has been met follow in the section “Accomplishment of Goals and Objectives”. % Accomplished as of January 2005 Resource Area Objective 25 50 75 100 PFC By 2000, complete a PFC assessment within a selected subsection. 100% By 2007, develop at least one fire management plan for a priority area within each of the seven 100% subsections. Fire By 2005, initiate a program to burn a minimum 2,000 acres annually for habitat improvement, fuels 100% management, and forest health, consistent with approved fire management plans. 0% Lands Remove utility facilities located in avoidance or exclusion areas as it becomes practical to do so. This will be amended to be a guideline By 2007, complete watershed improvement needs backlog in the Lemhi/Medicine Lodge, Big Hole 25% Mountains, and Caribou Range Mountains Subsections. By 2007, verify watershed improvement needs identified in the Teton Basin Study. 50% Fish, Water, and By 2007, inventory watershed improvement needs on the Centennial Mountains, Madison-Pitchstone 50% Riparian Plateaus, and Teton Range Subsections. By 1999, coordinate with ID & WY to reassess the health of native cutthroat trout populations within the Lemhi/Medicine Lodge, Centennial Mountains, Island Park, Madison-Pitchstone Plateaus, and Teton 100% Range Subsections. -

CURRICULUM VITAE University of Idaho

CURRICULUM VITAE University of Idaho NAME: Erickson, Luke V. DATE: October 31, 2019 RANK OR TITLE: Associate Professor Extension Specialist – Personal Finance DEPARTMENT: School of Family and Consumer Sciences OFFICE LOCATION: University of Idaho OFFICE PHONE: (208) 538-9936 Caldwell Research & Extension Center EMAIL: [email protected] 1904 E. Chicago St., Suite AB Caldwell, ID 83605 DATE OF FIRST EMPLOYMENT AT U of I: October 2, 2006 DATE OF TENURE: March 31, 2011 DATE OF PRESENT RANK OR TITLE: October 1, 2017 EDUCATION BEYOND HIGH SCHOOL: Degrees: Ph.D. 2018, Instructional Design, Idaho State University, Pocatello, Idaho. M.S. 2006, Consumer Science, Utah State University, Logan, Utah. B.S. 2004, Economics, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah. A.A. 1998, Generals, Business emphasis, Ricks College, Rexburg, Idaho. Certificates and Licenses: Accredited Financial Counselor (AFC) – Issued through the Association for Financial Counseling Planning and Education, Columbus, OH. 2009-present. 4-H Shooting sports training certification, rifles and handguns. St. Anthony, ID. 2009. Wyoming and Idaho certification. National Institutes of Health (NIH) Protecting Human Research Participants, Certificate of Completion (#196540), 2009. EXPERIENCE: Teaching, Extension and Research Appointments: Associate Professor, Personal Finance Specialist, University of Idaho, Boise Center, Boise, Idaho 2017- present. Associate Professor, Personal Finance, University of Idaho Extension, Madison County Extension Office, Rexburg, Idaho, 2011-2017. Assistant Professor, Personal Finance, University of Idaho Extension, Madison County Extension Office, Rexburg, Idaho, 2006 – 2011. Teaching Assistant of Consumer Science, Utah State University, Logan, Utah, 2004-2006. Research Assistant of Consumer Science, Utah State University, Logan, Utah, 2004-2006. Academic Administrative Appointments: Madison County Office Chair, 2011-2017. -

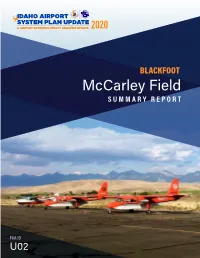

Mccarley Field SUMMARY REPORT

2020 BLACKFOOT McCarley Field SUMMARY REPORT FAA ID U02 U02 Understanding the Airport AERIAL Blackfoot is a city in southeastern Idaho located along Interstate 15 halfway between Idaho FIREFIGHTING Falls and Pocatello with an estimated population of just under 12,000 people. Blackfoot sits in the Upper Snake River Valley and is colloquially known as the “Potato Capital of the World”, producing more potatoes than anywhere else in the country. The surrounding area is home to Yellowstone National Park, Sun Valley, Jackson Hole, Craters of the Moon, ski areas and Blackfoot hosts the Eastern Idaho State Fair each year. McCarley Field (U02) MEDICAL is a general aviation airport that is owned and operated by the City of Blackfoot. The OPERATIONS field is located one mile north of the central business district of Blackfoot. The airport has an instrument approach, making it a viable alternate to Pocatello and Twin Falls, even in poor weather conditions. The field is primarily used by recreation fliers and is known as the “Gateway to the Backcountry”. U02 has aircraft arrive from every state west of the Mississippi River as visitors travel into central Idaho’s AERIAL AGRICULTURAL wilderness areas. Since the 2010 study was completed, McCarley Field has SPRAYING conducted expansion and maintenance projects to increase the capability and lifespan of the field. There are multiple businesses based at U02 that provide many services, including aircraft maintenance and repair, fueling, and flight training. Finally, the Idaho wing of the Civil Air Patrol is headquartered in GATEWAY TO THE Blackfoot and has a hangar on the field. -

Emmett High School and TVMSC Projects Earn Top Honors at Third Annual Western Idaho Science & Engineering Fair

CONTACT: Angela Hemingway, 208.332.1726, [email protected] Crispin Gravatt, 208.488.0946, [email protected] Tony Harrison, 208.332.1726, [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Emmett High School and TVMSC projects earn top honors at third annual Western Idaho Science & Engineering Fair BOISE, Idaho (March 20, 2019) — Judges at the 2019 Western Idaho Science & Engineering Fair declared projects from Emmett High School and Treasure Valley Mathematics and Science Center the Best of Fair award winners and one from Nampa High School as the Fair Runner Up. They were among 84 projects presented by 108 students from seven Treasure Valley schools at the third annual event, which the Idaho STEM Action Center staged March 15 at Boise State University. Best of Fair winners Emmett High School student Lukas Keller’s “Testing ‘Meat-Free’ Chicken Nuggets for Gamma Globulin” earned one of two Best of Fair awards, as well as the Best in Category award in Physical Sciences and a Category Gold award. “Bacteriophage Isolation and Identification of Antibacterial Properties” submitted by Melina Mohammadi from Treasure Valley Mathematics and Science Center in Boise garnered the other Best of Fair award. In addition, she earned a Best in Category in Animal, Biomedical, and Microbiological Sciences and a Category Gold award, as well as several special awards, including the First Place Idaho Academy of Science & Engineering Award, an Office of Naval Research Award, the Society for In Vitro Biology Award, and the U.S. Metric Association Award. On top of serious bragging rights, the two students and their mentors earned all-expense-paid trips to Phoenix to compete in the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair May 12-17. -

Eastern Idaho Guide

Eastern Idaho Rodeo & Fair Guide yellowstoneteton.org Fr m ee to roa Immerse yourself in the western experience Local Fairs | Must-See Rodeos | Western Heritage • Idaho’s oldest rodeo is the War Bonnet Round Up held each year in Idaho Falls. • Rodeo has a fanbase of more than 40 million people according to Sports Business Daily. • The word “rodeo” comes from the Spanish word rodear, which means “to encircle.” The origins of rodeo come from the gathering of cowboys after a cattle-drive to show their stuff on a bronco or bull. • Each year, 650 Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association- sanctioned events are held in North America. • There are nearly 2,000 county and state fairs held throughout the United States. Some state fairs draw more than one million visitors annually. • Outlaw Catering Company’s mouth- watering, jumbo Rebel Burger is a staple at the Eastern Idaho State Fair. So much so, it’s been named the state’s best fair food by Taste of Home Magazine. Their Bullseye Donut Burger is also as good as it sounds. RANCH HAND PHOTOGRAPHY RANCH HAND PHOTOGRAPHY 2 Eastern Idaho ARTS &CULTURE GUIDE Welcome! Welcome to the West. The home of cowboys and cowgirls, ranchers, ropers, farmers, and the like. Here, residents know how to work hard and play hard, and they welcome visitors looking to experi- ence that lifestyle with open arms and a friendly hello. Eastern Idaho is filled with families who have deep roots in the land and is blanketed by fields of crops that spread for miles and herds of cattle roaming the hillside. -

CURRICULUM VITAE for EXTENSION EDUCATOR FACULTY University of Idaho

CURRICULUM VITAE FOR EXTENSION EDUCATOR FACULTY University of Idaho NAME: Morrisroe-Aman, Bridget DATE: August 22, 2018 RANK OR TITLE: Assistant Extension Professor Extension Educator DEPARTMENT: University of Idaho Extension, Southern District College of Agricultural and Life Sciences OFFICE LOCATION: UI Extension, Ada County OFFICE PHONE: (208) 287-5900 5880 Glenwood St. FAX: (208) 287-5909 Boise, ID 83714 EMAIL: [email protected] WEB: uidaho.edu/extension/county/ada DATE OF FIRST EMPLOYMENT AT UI: May 26, 2001 DATE OF TENURE: Untenured DATE OF PRESENT RANK OR TITLE: December 1, 2016 EDUCATION BEYOND HIGH SCHOOL: Degrees: M.A. 2011, Social Work, Boise State University, Boise, Idaho. B.A. 1998, Social Work, Boise State University, Boise, Idaho. Additional Coursework for Credit: Global Nutrition, University of Idaho, Spring 2009 Certificates and Licenses: Idaho School Social Work Endorsement, 2013 - Present Idaho Social Work Master Level License, 2012 – Present Master Food Safety Advisor Certification, 2010 – Present National Diabetes Prevention Program, 2017- Present Certified Workplace Wellness Program Coordinator, 2017 – Present Certified 4-H Yoga for Youth Instructor, 2018 -Present EXPERIENCE: Teaching, Extension and Research Appointments: Assistant Extension Professor, University of Idaho, Ada County Extension Office, Boise ID, December 2016-Present Eat Smart Idaho Program Coordinator, University of Idaho. Responsibilities – Coordinate the Eat Smart Idaho program in the greater Treasure Valley area. Recruit, hire, and train nutrition advisors. Work annual grant proposals, collect and report data, and complete reports. Manage budgets, process weekly paperwork and maintain inventory. Jan. 2005 – Nov. 2016 Children, Youth, and Families at Risk (CYFAR) Program Coordinator, University of Idaho. Responsibilities – Develop and coordinate multi-county programs, after school and out of school programs and camps. -

4H-Ffa-Book-Full.Pdf

J R 2 0E x 1 h 5 ib it o r s H a n d b o o k Greetings! We look forward to your participation in the 118th annual Western Idaho fair. We invite you to join in the fun and exhibit your talents at the fair…it’s easy! Whether you grow carrots, quilt, bake or paint, we have a category to showcase your goods. The fair has a wide variety of activities centered on education and entertainment for your whole family to enjoy! Fairgoers can learn about urban gardening, animals from small to large, or activities like painting, quilting, and ceramics. There are opportunities to support our 4-H and FFA participants with the Jr. Livestock Sale, take in a Horse show, and even participate in a Skillet Toss! Some of our entertainment options include: Hans Bruijn • DISH Grandstand Concerts including Jerrod Niemann, Theory of a Premium Office Coordinator Deadman, Gary Allan, and Pat Benatar and Neil Giraldo Premium Office Phone: 208-287-5663 • Grounds acts including Sea Lion Encounters, Kachunga Alligator Show, Premium Office Fax: 208-287-5665 BMX Pro Trick Riders, Circus Imagination, and Meet the Animals • Stage shows including hypnotist Michael Mezmer, sword swallower Dan Meyer, and Divas through the Decades • Ag education opportunitiesoppo at the Farmers Market, Urban Garden, and Simplot Ag Pavilion Additionally, Boise Riverside RV Park offers Boise Greenbelt access, horseshoe pits, pancake breakfasts, new showers and laundry, and so much more. For reservations and other information, check out IdahoFair.com. Your Extension Team: (L to R) Educators Brian Luckey, Dana Kolstad, Nikola Dalton; FFA Advisor Jack Blattner; 4-H We look forward to your participation in Western Idaho Fair. -

January Term, A.D., 2017 Caldwell, Idaho January 9, 2017

FIRST DAY OF THE JANUARY TERM, A.D., 2017 CALDWELL, IDAHO JANUARY 9, 2017 PRESENT: Commissioner Tom Dale, Chairman Commissioner Pam White Commissioner Steve Rule Deputy Clerk Monica Reeves / Jenen Ross APPROVED PURCHASE ORDER The Board approved the following purchase order(s): Columbia Electric Supply in the amount of $2,133.00 for the Facilities Department SIGNED RESOLUTION FOR ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGE LICENSE The Board approved an Alcoholic Beverage License for: I.C.A.N. Foods, Inc., dba The Griddle (See Resolution No. 17-004) SWEARING-IN CEREMONY FOR NEWLY ELECTED OFFICIALS A swearing-in ceremony was held this morning in the public meeting room of the Canyon County Administration Building. The ceremony began at 9:00 a.m. with the following people in attendance: Commissioners Steve Rule, Pam White and Tom Dale, Clerk Chris Yamamoto, Chief Deputy Clerk Drew Maffei, Prosecutor Bryan Taylor, Chief Civil Deputy P.A. Sam Laugheed, Sheriff Kieran Donahue, Assessor Gene Kuehn, Chief Deputy Assessor Joe Cox, Treasurer Tracie Lloyd, Chief Deputy Treasurer Nancy Seal, department administrators, and employees, judicial and city representatives, as well as Deputy Clerk Monica Reeves. The Clerk of the Board administered the oath of office to the following officials: Commissioner Pam White, Commissioner Tom Dale, Sheriff Kieran Donahue and Prosecutor Bryan Taylor. The oaths of office are on file with this day’s minute entry. The ceremony concluded at approximately 9:20 a.m. CONSIDER APPOINTING CHAIRMAN AND VICE-CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD OF CANYON COUNTY COMMISSIONERS The Board met today at 10:18 a.m. to consider appointing a chairman and vice-chairman of the Board of Canyon County Commissioners. -

Yellowstone & Grand Teton National Park

_0 (J) ~o r---.. a:::: o u.. ~...-J D- O Z« ~ ~ (J) yellowstoneteton.org (800) 634·3246 FREE GUIDE & MAP: Best places to visit, explore, camp, eat, shop, stay, and play while in Eastern Idaho 4 South Fork Lodge, is an angler's paradise, offering expert guided tours on some of the best fly-fishing waters in the country. All inclusive packages offer everything you need to spend your days fishing on the South Fork of the Snake and your evenings enjoying the comforts of our luxurious waterside lodge. NATURALRETREATS.COM • (888) 451 · 0156 22 Miles from West Brand New 25 Room Hotel! - WELCOME 5 DAY 1 IDAHO FALLS 16 GETTING HERE 6 DAY 2 CRUISIN' ALONG 8 RIGBY & REXBURG 22 YELLOWSTONE TETON DAY 3 TERRITORY MAP 8 ST. ANTHONY, ISLAND PARK, & ASHTON 26 YELLOWSTONE-GRAND DAY 4 TETON LOOP MAP 10 YELLOWSTONE & GRAND TETON 32 CALENDAR 14 DAY 5 JACKSON HOLE 34 DAY 6 ~ TETON VALLEY 36 DAY 7 IDAHO SWAN VALLEY, HEISE, & RIRIE 42 visitidaho.org GENERAL INFO 46 16-VI-Ol : SOM MEMBERSHIP DIRECTORY 50 LODGING GUIDES 52 4 ADVENTURE! We're glad you're here! You're in good company! People have been coming to Eastern Idaho for centuries-first Native Americans, who chose the verdant va\!eys as places to spend summers, then fur trappers, who harvested the richness of the wildlife here, not stopping to seule. Early pioneers turned sagebrush mead ows into productive fann fields; eventually, game tracks became roadways and homesteads were established. Small communities began to thrive and build histories of their own.