Ecotourism: Potential for Conservation and Sustainable Use of Tropical Forests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preliminary Phytochemical and Antimycobacterial Investigation of Some Selected Medicinal Plants of Endau Rompin, Johor, Malaysia

Journal of Science and Technology, Vol. 10 No. 2 (2018) p. 30-37 Preliminary Phytochemical and Antimycobacterial Investigation of Some Selected Medicinal Plants of Endau Rompin, Johor, Malaysia Shuaibu Babaji Sanusi*, Mohd Fadzelly Abu Bakar, Maryati Mohamed and Siti Fatimah Sabran Faculty of Applied Sciences and Technology, Universiti Tun Hussein Onn Malaysia (UTHM), Pagoh Educational Hub, 84600 Pagoh, Johor, Malaysia. Received 30 September 2017; accepted 27 February 2018; available online 1 August 2018 DOI: https://10.30880/jst.2018.10.02.005 Abstract: Tuberculosis (TB), the primary cause of morbidity and mortality globally is a great public health challenge especially in developing countries of Africa and Asia. Existing TB treatment involves multiple therapies and requires long duration leading to poor patient compliance. The local people of Kampung Peta, Endau Rompin claimed that local preparations of some plants are used in a TB symptoms treatment. Hence, there is need to validate the claim scientifically. Thus, the present study was designed to investigate the in vitro anti-mycobacterial properties and to screen the phytochemicals present in the extracts qualitatively. The medicinal plants were extracted using decoction and successive maceration. The disc diffusion assay was used to evaluate the anti-mycobacterial activity, and the extracts were subjected to qualitative phytochemical screening using standard chemical tests. The findings revealed that at 100 mg/ml concentration, the methanol extract of Nepenthes ampularia displayed largest inhibition zone (DIZ=18.67 ± 0.58), followed by ethyl acetate extract of N. ampularia (17.67 ± 1.15) and ethyl acetate extract of Musa gracilis (17.00 ± 1.00). The phytochemical investigation of these extracts showed the existence of tannins, flavonoids, alkaloids, terpenoids, saponins, and steroids. -

Btsisi', Blandas, and Malays

BARBARA S. NOWAK Massey University SINGAN KN÷N MUNTIL Btsisi’, Blandas, and Malays Ethnicity and Identity in the Malay Peninsula Based on Btsisi’ Folklore and Ethnohistory Abstract This article examines Btsisi’ myths, stories, and ethnohistory in order to gain an under- standing of Btsisi’ perceptions of their place in Malaysia. Three major themes run through the Btsisi’ myths and stories presented in this paper. The first theme is that Austronesian-speaking peoples have historically harassed Btsisi’, stealing their land, enslaving their children, and killing their people. The second theme is that Btsisi’ are different from their Malay neighbors, who are Muslim; and, following from the above two themes is the third theme that Btsisi’ reject the Malay’s Islamic ideal of fulfilment in pilgrimage, and hence reject their assimilation into Malay culture and identity. In addition to these three themes there are two critical issues the myths and stories point out; that Btsisi’ and other Orang Asli were original inhabitants of the Peninsula, and Btsisi’ and Blandas share a common origin and history. Keywords: Btsisi’—ethnic identity—origin myths—slaving—Orang Asli—Peninsular Malaysia Asian Folklore Studies, Volume 63, 2004: 303–323 MA’ BTSISI’, a South Aslian speaking people, reside along the man- grove coasts of the Kelang and Kuala Langat Districts of Selangor, HWest Malaysia.1* Numbering approximately two thousand (RASHID 1995, 9), Btsisi’ are unique among Aslian peoples for their coastal location and for their geographic separation from other Austroasiatic Mon- Khmer speakers. Btsisi’, like other Aslian peoples have encountered histori- cally aggressive and sometimes deadly hostility from Austronesian-speaking peoples. -

CBD Sixth National Report

SIXTH NATIONAL REPORT OF MALAYSIA to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) December 2019 i Contents List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................... iv List of Tables ................................................................................................................................................ vi List of Acronyms ........................................................................................................................................... vi Foreword ..................................................................................................................................................... vii Preamble ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................. 3 CHAPTER 1: UPDATED COUNTRY BIODIVERSITY PROFILE AND COUNTRY CONTEXT ................................... 1 1.1 Malaysia as a Megadiverse Country .................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Major pressures and factors to biodiversity loss ................................................................................. 3 1.3 Implementation of the National Policy on Biological Diversity 2016-2025 ........................................ -

Buku Daftar Senarai Nama Jurunikah Kawasan-Kawasan Jurunikah Daerah Johor Bahru Untuk Tempoh 3 Tahun (1 Januari 2016 – 31 Disember 2018)

BUKU DAFTAR SENARAI NAMA JURUNIKAH KAWASAN-KAWASAN JURUNIKAH DAERAH JOHOR BAHRU UNTUK TEMPOH 3 TAHUN (1 JANUARI 2016 – 31 DISEMBER 2018) NAMA JURUNIKAH BI NO KAD PENGENALAN MUKIM KAWASAN L NO TELEFON 1 UST. HAJI MUSA BIN MUDA (710601-01-5539) 019-7545224 BANDAR -Pejabat Kadi Daerah Johor Bahru (ZON 1) 2 UST. FAKHRURAZI BIN YUSOF (791019-01-5805) 013-7270419 3 DATO’ HAJI MAHAT BIN BANDAR -Kg. Tarom -Tmn. Bkt. Saujana MD SAID (ZON 2) -Kg. Bahru -Tmn. Imigresen (360322-01-5539) -Kg. Nong Chik -Tmn. Bakti 07-2240567 -Kg. Mahmodiah -Pangsapuri Sri Murni 019-7254548 -Kg. Mohd Amin -Jln. Petri -Kg. Ngee Heng -Jln. Abd Rahman Andak -Tmn. Nong Chik -Jln. Serama -Tmn. Kolam Air -Menara Tabung Haji -Kolam Air -Dewan Jubli Intan -Jln. Straits View -Jln. Air Molek 4 UST. MOHD SHUKRI BIN BANDAR -Kg. Kurnia -Tmn. Melodies BACHOK (ZON 3) -Kg. Wadi Hana -Tmn. Kebun Teh (780825-01-5275) -Tmn. Perbadanan Islam -Tmn. Century 012-7601408 -Tmn. Suria 5 UST. AYUB BIN YUSOF BANDAR -Kg. Melayu Majidee -Flat Stulang (771228-01-6697) (ZON 4) -Kg. Stulang Baru 017-7286801 1 NAMA JURUNIKAH BI NO KAD PENGENALAN MUKIM KAWASAN L NO TELEFON 6 UST. MOHAMAD BANDAR - Kg. Dato’ Onn Jaafar -Kondo Datin Halimah IZUDDIN BIN HASSAN (ZON 5) - Kg. Aman -Flat Serantau Baru (760601-14-5339) - Kg. Sri Paya -Rumah Pangsa Larkin 013-3352230 - Kg. Kastam -Tmn. Larkin Perdana - Kg. Larkin Jaya -Tmn. Dato’ Onn - Kg. Ungku Mohsin 7 UST. HAJI ABU BAKAR BANDAR -Bandar Baru Uda -Polis Marin BIN WATAK (ZON 6) -Tmn. Skudai Kanan -Kg. -

A Global Overview of Protected Areas on the World Heritage List of Particular Importance for Biodiversity

A GLOBAL OVERVIEW OF PROTECTED AREAS ON THE WORLD HERITAGE LIST OF PARTICULAR IMPORTANCE FOR BIODIVERSITY A contribution to the Global Theme Study of World Heritage Natural Sites Text and Tables compiled by Gemma Smith and Janina Jakubowska Maps compiled by Ian May UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre Cambridge, UK November 2000 Disclaimer: The contents of this report and associated maps do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP-WCMC or contributory organisations. The designations employed and the presentations do not imply the expressions of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP-WCMC or contributory organisations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or its authority, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION 1.0 OVERVIEW......................................................................................................................................................1 2.0 ISSUES TO CONSIDER....................................................................................................................................1 3.0 WHAT IS BIODIVERSITY?..............................................................................................................................2 4.0 ASSESSMENT METHODOLOGY......................................................................................................................3 5.0 CURRENT WORLD HERITAGE SITES............................................................................................................4 -

Limits of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) in Malaysia: Dam Politics, Rent-Seeking, and Conflict

sustainability Article Limits of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) in Malaysia: Dam Politics, Rent-Seeking, and Conflict Peter Ho 1, Bin Md Saman Nor-Hisham 2,* and Heng Zhao 1 1 Zijingang Campus, School of Public Affairs, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310058, China; [email protected] (P.H.); [email protected] (H.Z.) 2 Department of Town and Regional Planning, Universiti Teknologi Mara, Cawangan Perak 32610, Malaysia * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 6 November 2020; Accepted: 7 December 2020; Published: 14 December 2020 Abstract: Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is often portrayed as a policy measure that can mitigate the environmental influence of corporate and government projects through objective, systematic, and value-free assessment. Simultaneously, however, research has also shown that the larger political context in which the EIA is embedded is crucial in determining its influence on decision-making. Moreover, particularly in the case of mega-projects, vested economic interests, rent-seeking, and politics may provide them with a momentum in which the EIA risks becoming a mere formality. To substantiate this point, the article examines the EIA of what is reportedly Asia’s largest dam outside China: the Bakun Hydro-electric Project (BHP) in Malaysia. The study is based on mixed methods, particularly, qualitative research (semi-structured interviews, participatory observation, and archival study) coupled to a survey conducted in 10 resource-poor, indigenous communities in the resettlement area. It is found that close to 90% of the respondents are dissatisfied with their participation in the EIA, while another 80% stated that the authorities had conducted the EIA without complying to the procedures. -

5- Informe ASEAN- Centre-1.Pdf

ASEAN at the Centre An ASEAN for All Spotlight on • ASEAN Youth Camp • ASEAN Day 2005 • The ASEAN Charter • Visit ASEAN Pass • ASEAN Heritage Parks Global Partnerships ASEAN Youth Camp hen dancer Anucha Sumaman, 24, set foot in Brunei Darussalam for the 2006 ASEAN Youth Camp (AYC) in January 2006, his total of ASEAN countries visited rose to an impressive seven. But he was an W exception. Many of his fellow camp-mates had only averaged two. For some, like writer Ha Ngoc Anh, 23, and sculptor Su Su Hlaing, 19, the AYC marked their first visit to another ASEAN country. Since 2000, the AYC has given young persons a chance to build friendships and have first hand experiences in another ASEAN country. A project of the ASEAN Committee on Culture and Information, the AYC aims to build a stronger regional identity among ASEAN’s youth, focusing on the arts to raise awareness of Southeast Asia’s history and heritage. So for twelve days in January, fifty young persons came together to learn, discuss and dabble in artistic collaborations. The theme of the 2006 AYC, “ADHESION: Water and the Arts”, was chosen to reflect the role of the sea and waterways in shaping the civilisations and cultures in ASEAN. Learning and bonding continued over visits to places like Kampung Air. Post-camp, most participants wanted ASEAN to provide more opportunities for young people to interact and get to know more about ASEAN and one another. As visual artist Willy Himawan, 23, put it, “there are many talented young people who could not join the camp but have great ideas Youthful Observations on ASEAN to help ASEAN fulfill its aims.” “ASEAN countries cooperate well.” Sharlene Teo, 18, writer With 60 percent of ASEAN’s population under the age of thirty, young people will play a critical role in ASEAN’s community-building efforts. -

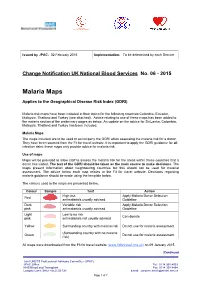

Change Notification No 06 2015

Northern Ireland BLOOD TRANSFUSION SERVICE Issued by JPAC: 02 February 2015 Implementation: To be determined by each Service Change Notification UK National Blood Services No. 06 - 2015 Malaria Maps Applies to the Geographical Disease Risk Index (GDRI) Malaria risk maps have been included in their topics for the following countries Colombia, Ecuador, Malaysia, Thailand and Turkey (see attached). Advice relating to use of these maps has been added to the malaria section of the preliminary pages as below. An update on the advice for Sri Lanka, Colombia, Malaysia, Thailand,and Turkey has been included. Malaria Maps The maps included are to be used to accompany the GDRI when assessing the malaria risk for a donor. They have been sourced from the Fit for travel website. It is important to apply the GDRI guidance for all infection risks; these maps only provide advice for malaria risk. Use of maps Maps will be provided to allow staff to assess the malaria risk for the areas within these countries that a donor has visited. The text of the GDRI should be taken as the main source to make decisions. The maps present information about neighbouring countries but this should not be used for malarial assessment. The advice below each map relates to the Fit for travel website. Decisions regarding malaria guidance should be made using the template below. The colours used in the maps are presented below. Colour Sample Text Action High risk Apply Malaria Donor Selection Red antimalarials usually advised Guideline Dark Variable risk Apply Malaria Donor -

The Proposed Endau‑Rompin National Park: the Mass Media and the Evolution of a Controversy

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. The proposed Endau‑Rompin national park: the mass media and the evolution of a controversy Leong, Yueh Kwong. 1989 Leong, Y. K. (1989). The proposed Endau‑Rompin national park: the mass media and the evolution of a controversy. In AMIC‑NCDC‑BHU Seminar on Media and the Environment : Varanasi, Feb 26‑Mar 1, 1989. Singapore: Asian Mass Communication Research and Information Centre. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/86416 Downloaded on 26 Sep 2021 06:58:55 SGT ATTENTION: The Singapore Copyright Act applies to the use of this document. Nanyang Technological University Library The Proposed Endau-Rompin National Park: The Mass Media And The Evolution Of A Controversy By Leong Yueh Kwong Paper No.8 ATTENTION: The Singapore Copyright Act applies to the use of this document. Nanyang Technological University Library THE PROPOSED ENDAU-ROMPIN NATIONAL PARK THE MASS MEDIA AND THE EVOLUTION OF A CONTROVERSY Introduction The proposed Endau-Rompin National Park and the controversy surrounding it is now regarded as a landmark in the conservation efforts in Malaysia. The controversy began in 1977 when a state government gave out logging licenses for part of a proposed national park. There was intense public opposition to the logging. The opposition to the logging took on the form of a national campaign with almost daily coverage in the mass media for over 6 months until logging was stopped. There was a lull in'public attention and interest in the proposed national park between 1978 to the middle of 1985. -

Senarai Bilangan Pemilih Mengikut Dm Sebelum Persempadanan 2016 Johor

SURUHANJAYA PILIHAN RAYA MALAYSIA SENARAI BILANGAN PEMILIH MENGIKUT DAERAH MENGUNDI SEBELUM PERSEMPADANAN 2016 NEGERI : JOHOR SENARAI BILANGAN PEMILIH MENGIKUT DAERAH MENGUNDI SEBELUM PERSEMPADANAN 2016 NEGERI : JOHOR BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA PERSEKUTUAN : SEGAMAT BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NEGERI : BULOH KASAP KOD BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NEGERI : 140/01 SENARAI DAERAH MENGUNDI DAERAH MENGUNDI BILANGAN PEMILIH 140/01/01 MENSUDOT LAMA 398 140/01/02 BALAI BADANG 598 140/01/03 PALONG TIMOR 3,793 140/01/04 SEPANG LOI 722 140/01/05 MENSUDOT PINDAH 478 140/01/06 AWAT 425 140/01/07 PEKAN GEMAS BAHRU 2,391 140/01/08 GOMALI 392 140/01/09 TAMBANG 317 140/01/10 PAYA LANG 892 140/01/11 LADANG SUNGAI MUAR 452 140/01/12 KUALA PAYA 807 140/01/13 BANDAR BULOH KASAP UTARA 844 140/01/14 BANDAR BULOH KASAP SELATAN 1,879 140/01/15 BULOH KASAP 3,453 140/01/16 GELANG CHINCHIN 671 140/01/17 SEPINANG 560 JUMLAH PEMILIH 19,072 SENARAI BILANGAN PEMILIH MENGIKUT DAERAH MENGUNDI SEBELUM PERSEMPADANAN 2016 NEGERI : JOHOR BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA PERSEKUTUAN : SEGAMAT BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NEGERI : JEMENTAH KOD BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NEGERI : 140/02 SENARAI DAERAH MENGUNDI DAERAH MENGUNDI BILANGAN PEMILIH 140/02/01 GEMAS BARU 248 140/02/02 FORTROSE 143 140/02/03 SUNGAI SENARUT 584 140/02/04 BANDAR BATU ANAM 2,743 140/02/05 BATU ANAM 1,437 140/02/06 BANDAN 421 140/02/07 WELCH 388 140/02/08 PAYA JAKAS 472 140/02/09 BANDAR JEMENTAH BARAT 3,486 140/02/10 BANDAR JEMENTAH TIMOR 2,719 140/02/11 BANDAR JEMENTAH TENGAH 414 140/02/12 BANDAR JEMENTAH SELATAN 865 140/02/13 JEMENTAH 365 140/02/14 -

Conservation Effort of Amphibia at Taman Negara Johor Endau Rompin

Journal of Science and Technology, Vol. 9 No. 4 (2017) p. 122-125 Conservation Effort of Amphibia at Taman Negara Johor Endau Rompin Muhammad Taufik Awang1, Maryati Mohamed1*, Norhayati Ahmad2 and Lili Tokiman3 1Centre of Research for Sustainable Uses of Natural Resources, Department of Technology and Natural Resources, Faculty of Applied Sciences and Technology, Universiti Tun Hussein Onn Malaysia, Kampus Pagoh, KM 1, Jalan Panchor 84000 Muar Johor, Malaysia 2School of Environment & Natural Resource Sciences, Faculty of Science & Technology, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 UKM Bangi, Selangor, Malaysia. 3Johor National Parks Corporation, Aras 1, Bangunan Dato' Mohamad Salleh Perang, Kota Iskandar, 79576 Iskandar Putri, Johor, Malaysia. Received 30 September 2017; accepted 30 November 2017; available online 28 December 2017 Abstract: Taman Negara Johor Endau Rompin (TNJER) is the largest piece of protected area in the southern part of Peninsula Malaysia. The Endau part of the park, covering the size of 48,905 ha, is in the state of Johor. This study sampled a specific area of TNJER along three streams (Sungai Daah, Sungai Kawal and Sungai Semawak). Anurans were sampled along each stream using Visual Encounter Survey (VES). Twenty species were collected from this small plot of 2 ha. Using species cumulative curve, the 20 species apparently reached the asymptote Further analyses, involving nine estimators showed that chances of finding new species ranges from 20 (MMeans) to 27 (Jack 2). Based on the species cumulative curve, MMeans estimator was found to be more realistic. From a separate study to produce a checklist of anurans for TNJER based on several expeditions, carried out from several parts of TNJER and collections made from 1985 to 2015, 52 species were recorded. -

Assessing Cumulative Watershed Effects by Zig-Zag Pebble Count Method

ASSESSING CUMULATIVE WATERSHED EFFECTS BY ZIG-ZAG PEBBLE COUNT METHOD TIMOTHY NEX BETIN UNIVERSITI TEKNOLOGI MALAYSIA i ASSESSING CUMULATIVE WATERSHED EFFECTS BY ZIG-ZAG PEBBLE COUNT METHOD TIMOTHY NEX BETIN A project report submitted as a partial fulfilment of the requirement for award of the degree of Masters in Engineering (Civil-Environmental Management) Faculty of Civil Engineering Universiti Teknologi Malaysia JULY, 2006 v ABSTRACT Cumulative effects are the combined effects of multiple activities for example such as agricultural activities, logging activities, unpaved roads, grazing and recreation, while the watershed effects are those which involve processes of water transport. Almost all impacts are influenced by multiple activities, so almost all impacts must be evaluated as cumulative impacts rather than as individual impacts. This paper attempts to present and discuss the cumulative effects occur within the Endau watershed, current issues on water resource planning and management and the approaches/strategies required to confront present and emerging critical problems. In this study, the deposition of fine sediment (particle size < 8 mm) are main concern because this can adversely affect macro-invertebrates and fish by filling pools and interstitial spaces, decreasing inter-gravel dissolved oxygen concentrations, and inhibiting fish fry emergence. The bed material particle-size distribution is believed to be one of the first channel characteristics to change in response to management activities. This study was carry out on Jasin River as reference stream while Mengkibol River and Sembrong River and as study stream. The method for assessing these CWEs is by using Zig-Zag pebble count method. As result, the sediment loading is in the order of Sembrong River > Mengkibol River > Jasin River.