NATIONAL PARKS I0 September, 1987 Mr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Confirmed Breeding Record of Plume-Toed Swiftlet Collocalia Affinis in Singapore

BirdingASIA 31 (2019)(2019): 85–87 85 BREEDING RECORD First confirmed breeding record of Plume-toed Swiftlet Collocalia affinis in Singapore ALFRED CHIA, DING LI YONG, KIM CHUAH LIM, MOVIN NYANASENGERAN, YONG CHEE KEITA SIN, KIM KEANG LIM & SENG BENG YEO Historically the tiny Collocalia swiftlets resident In the meantime, the results of a detailed in both the lowlands and higher altitudes of analysis of the taxonomy of Collocalia swiftlets in Peninsular Malaysia were designated Glossy the Indo-Pacific region (Rheindt et al. 2017) led to Swiftlet C. esculenta cyanoptila (Wells 1999). the proposal of radical changes to the established However, the species was rare on Singapore taxonomy; this was a big challenge due to the mainland, with fewer than 10 records per year, all morphological uniformity of these taxa. Rheindt apparently in the period November to February, et al. (2017) studied the evolutionary history of the which is the non-breeding season in Malaysia complex, combining new biometric measurements (Wells 1999). In recent times the frequency of and plumage assessment of museum specimens records in Singapore has increased, including a with novel as well as previously published group of up to seven birds at Bukit Batok Nature molecular data, with a total of 809 individuals Park in January 2005, as well as regular records representative of 32 taxa being assessed. The thereafter in and at the periphery of the Central authors propose changing the classification of Nature Reserves, and its status was revised to white-bellied swiftlets, for which just two species ‘uncommon’ (Yong et al. 2017, Lim 2018). -

ATIU SWIFTLET KOPEKA (Aerodramus Sawtelli): SPECIES STATUS REPORT 2020

ATIU SWIFTLET KOPEKA (Aerodramus sawtelli): SPECIES STATUS REPORT 2020 Atiu Swiftlet James J. S. Johnson Author: Te Ipukarea Society Te Ipukarea Society, PO Box 649, Rarotonga Cook Islands Funded with the support of: The Ridge to Reef Project through the National Environment Service, funded by Global Environment Facility (GEF) and facilitated by United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Species status report – Kopeka, Atiu Swiftlet (Aerodramus sawtelli) Summary The Atiu swiftlet (Aerodramus sawtelli), known locally as the kopeka, is endemic to the island of Atiu within the Cook Islands and is listed under the IUCN Red List as ‘Vulnerable’ (BirdLife International, 2016; IUCN 2020). Under the Ridge to Reef project (R2R), the Atiu Swiftlet was listed as a key terrestrial species for conservation activities (UNDP Project document, undated). Projects relevant to the kopeka that were initially planned to be implemented under R2R included: support for the kopeka conservation effort; support collaborative work amongst key stakeholders such as National Environment Service (NES), National Heritage Trust (NHT), the Atiu Island Council and Traditional Leaders to create and implement a Species Conservation Plan for this species; and to measure the population at the end of the project to gauge the overall results of the species conservation plan. The R2R baseline figures for the kopeka were recorded at 420 individuals in 2015. Species target goals upon completion of the R2R project were for ‘no net decline in population numbers’. During the four-year R2R programme 2015-19, later extended to 2021, no updated population surveys were conducted. In 2016 -2017, estimated population numbers were around 600 adults (M. -

Pacific Sheath-Tailed Bat American Samoa Emballonura Semicaudata Semicaudata Species Report April 2020

Pacific Sheath-tailed Bat American Samoa Emballonura semicaudata semicaudata Species Report April 2020 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office Honolulu, HI Cover Photo Credits Shawn Thomas, Bat Conservation International. Suggested Citation USFWS. 2020. Species Status Assessment for the Pacific Sheath Tailed Bat (Emballonura semicaudata semicaudata). April 2020 (Version 1.1). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office, Honolulu, HI. 57 pp. Primary Authors Version 1.1 of this document was prepared by Mari Reeves, Fred Amidon, and James Kwon of the Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office, Honolulu, Hawaii. Preparation and review was conducted by Gregory Koob, Megan Laut, and Stephen E. Miller of the Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office. Acknowledgements We thank the following individuals for their contribution to this work: Marcos Gorresen, Adam Miles, Jorge Palmeirim, Dave Waldien, Dick Watling, and Gary Wiles. ii Executive Summary This Species Report uses the best available scientific and commercial information to assess the status of the semicaudata subspecies of the Pacific sheath-tailed bat, Emballonura semicaudata semicaudata. This subspecies is found in southern Polynesia, eastern Melanesia, and Micronesia. Three additional subspecies of E. semicaudata (E.s. rotensis, E.s. palauensis, and E.s. sulcata) are not discussed here unless they are used to support assumptions about E.s. semicaudata, or to fill in data gaps in this analysis. The Pacific sheath-tailed bat is an Old-World bat in the family Emballonuridae, and is found in parts of Polynesia, eastern Melanesia, and Micronesia. It is the only insectivorous bat recorded from much of this area. -

Glossy Swiftlet (Christmas Island)

RECOVERY OUTLINE Glossy Swiftlet (Christmas Island) 1 Family Apodidae 2 Scientific name Collocalia esculenta natalis Lister, 1889 3 Common name Glossy Swiftlet (Christmas Island) 4 Conservation status Critically Endangered: A2ce, B1+2bce 5 Reasons for listing nestlings but may alter the whole ecology of the island A decline in the abundance of this subspecies of more by killing the dominant life-form, the Red Crab than 80% over the next three generations (30 years) is Gecaroidea natalis, and by farming scale insects, which predicted (Critically Endangered: A2) based on a damage the trees (O’Dowd et al., 1999). The ants decline in habitat quality (c) and the current rate of appear to consume all invertebrates (A. Andersen) spread of introduced ants (e). The already tiny area of including, presumably, the flying prey of the swiftlets. occupancy restricted to one location (B1) which may They may also invade nesting sites in caves. be reduced in area (2b), quality (c) and number of mature individuals in occupation (e) Estimate Reliability Extent of occurrence 137 km2 high trend stable high Area of occupancy 3 km2 low trend decreasing low No. of breeding birds 5,000 low trend decreasing low No. of sub-populations 1 high Generation time 4 years low 6 Infraspecific taxa 11 Information required There are about fifteen other subspecies in south-east Asia and the south-west Pacific. 11.1 Refine techniques for controlling Yellow Crazy Ants. 7 Past range and abundance Confined to Christmas I., Indian Ocean (Stokes, 12 Recovery objectives 1988). 12.1 Maintain existing population. 8 Present range and abundance 12.2 Control Yellow Crazy Ant. -

A Global Overview of Protected Areas on the World Heritage List of Particular Importance for Biodiversity

A GLOBAL OVERVIEW OF PROTECTED AREAS ON THE WORLD HERITAGE LIST OF PARTICULAR IMPORTANCE FOR BIODIVERSITY A contribution to the Global Theme Study of World Heritage Natural Sites Text and Tables compiled by Gemma Smith and Janina Jakubowska Maps compiled by Ian May UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre Cambridge, UK November 2000 Disclaimer: The contents of this report and associated maps do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP-WCMC or contributory organisations. The designations employed and the presentations do not imply the expressions of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP-WCMC or contributory organisations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or its authority, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION 1.0 OVERVIEW......................................................................................................................................................1 2.0 ISSUES TO CONSIDER....................................................................................................................................1 3.0 WHAT IS BIODIVERSITY?..............................................................................................................................2 4.0 ASSESSMENT METHODOLOGY......................................................................................................................3 5.0 CURRENT WORLD HERITAGE SITES............................................................................................................4 -

Bako National Park S60 Gunung Mulu NP

TOTAL COMBINE AREA (ha) NO NAME OF TPA (As of Nov 2020) GAZETTE No. GAZETTEMENT DATE LAND MARINE Total 1 Bako National Park S60 1 May, 1957 2,727.00 0.00 2,727.00 Gunung Mulu NP (All) Gunong Mulu National Park 2853 1 August, 1974 2 85,671.00 0.00 85,671.00 Gunong Mulu National Park (Ext.I) 2621 9 February, 2012 Gunong Mulu National Park (Ext. II) 3161 4 May, 2011 3 Niah National Park 50 23 November, 1974 3,139.00 0.00 3,139.00 4 Lambir Hills National Park 1899 15 May, 1975 6,949.00 0.00 6,949.00 Similajau NP (All) Similajau National Park 1337 25 November, 1976 8,996.00 5 22,120.00 Similajau National Park (1st Ext.) 2248 5 April, 2000 Similajau National Park (Ext.II) 130 23 May, 2000 13,124.00 6 Gunung Gading National Park 3289 1 August, 1983 4,196.00 0.00 4,196.00 7 Kubah National Park 2220 17 November, 1988 2,230.00 0.00 2,230.00 8 Batang Ai National Park 1288 28 February, 1991 24,040.00 0.00 24,040.00 9 Loagan Bunut National Park 2790 25 June, 1990 10,736.00 0.00 10,736.00 10 Tanjung Datu National Park 1102 16 March, 1994 752.00 627.00 1,379.00 11 Talang Satang National Park 3565 27 September, 1999 0.00 19,414.00 19,414.00 Maludam NP 12 Maludam National Park 1997 30 March, 2000 53,568.00 0.00 53,568.00 Maludam National Park (Ext 1) 2337 13 March, 2013 13 Bukit Tiban National Park 1998 17 February, 2000 8,000.00 0.00 8,000.00 14 Rajang Mangroves National Park 2833 29 May, 2000 9,373.00 0.00 9,373.00 Gunung Buda National Park (All) Gunung Buda National Park 189 14 September, 2000 15 11,307.00 0.00 11,307.00 Gunung Buda National Park (1st Ext) 3163 17 March, 2011 16 Kuching Wetland National Park 3512 24 July, 2002 6,610.00 0.00 6,610.00 Pulong Tau NP (All) 17 Pulong Tau National Park 919 10 January, 2005 69,817.00 0.00 69,817.00 Pulong Tau National Park(ext I) 2472 6 January, 2013 18 Usun Apau National Park 3153 5 May, 2005 49,355.00 0.00 49,355.00 19 Miri-Sibuti Coral Reefs National Park 1144 16 March, 2007 0.00 186,930.00 186,930.00 Santubong National Park (All) 20 Santubong National Park 2303 28 May, 2007 1,641.00 2,165.00 3,806.00 Santubong NP (Ext. -

5- Informe ASEAN- Centre-1.Pdf

ASEAN at the Centre An ASEAN for All Spotlight on • ASEAN Youth Camp • ASEAN Day 2005 • The ASEAN Charter • Visit ASEAN Pass • ASEAN Heritage Parks Global Partnerships ASEAN Youth Camp hen dancer Anucha Sumaman, 24, set foot in Brunei Darussalam for the 2006 ASEAN Youth Camp (AYC) in January 2006, his total of ASEAN countries visited rose to an impressive seven. But he was an W exception. Many of his fellow camp-mates had only averaged two. For some, like writer Ha Ngoc Anh, 23, and sculptor Su Su Hlaing, 19, the AYC marked their first visit to another ASEAN country. Since 2000, the AYC has given young persons a chance to build friendships and have first hand experiences in another ASEAN country. A project of the ASEAN Committee on Culture and Information, the AYC aims to build a stronger regional identity among ASEAN’s youth, focusing on the arts to raise awareness of Southeast Asia’s history and heritage. So for twelve days in January, fifty young persons came together to learn, discuss and dabble in artistic collaborations. The theme of the 2006 AYC, “ADHESION: Water and the Arts”, was chosen to reflect the role of the sea and waterways in shaping the civilisations and cultures in ASEAN. Learning and bonding continued over visits to places like Kampung Air. Post-camp, most participants wanted ASEAN to provide more opportunities for young people to interact and get to know more about ASEAN and one another. As visual artist Willy Himawan, 23, put it, “there are many talented young people who could not join the camp but have great ideas Youthful Observations on ASEAN to help ASEAN fulfill its aims.” “ASEAN countries cooperate well.” Sharlene Teo, 18, writer With 60 percent of ASEAN’s population under the age of thirty, young people will play a critical role in ASEAN’s community-building efforts. -

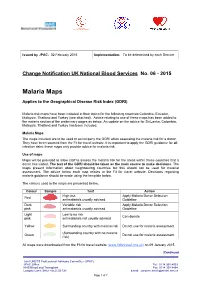

Change Notification No 06 2015

Northern Ireland BLOOD TRANSFUSION SERVICE Issued by JPAC: 02 February 2015 Implementation: To be determined by each Service Change Notification UK National Blood Services No. 06 - 2015 Malaria Maps Applies to the Geographical Disease Risk Index (GDRI) Malaria risk maps have been included in their topics for the following countries Colombia, Ecuador, Malaysia, Thailand and Turkey (see attached). Advice relating to use of these maps has been added to the malaria section of the preliminary pages as below. An update on the advice for Sri Lanka, Colombia, Malaysia, Thailand,and Turkey has been included. Malaria Maps The maps included are to be used to accompany the GDRI when assessing the malaria risk for a donor. They have been sourced from the Fit for travel website. It is important to apply the GDRI guidance for all infection risks; these maps only provide advice for malaria risk. Use of maps Maps will be provided to allow staff to assess the malaria risk for the areas within these countries that a donor has visited. The text of the GDRI should be taken as the main source to make decisions. The maps present information about neighbouring countries but this should not be used for malarial assessment. The advice below each map relates to the Fit for travel website. Decisions regarding malaria guidance should be made using the template below. The colours used in the maps are presented below. Colour Sample Text Action High risk Apply Malaria Donor Selection Red antimalarials usually advised Guideline Dark Variable risk Apply Malaria Donor -

Echolocation in Oilbirds and Swiftlets

REVIEW ARTICLE published: 28 May 2013 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00123 Echolocation in Oilbirds and swiftlets Signe Brinkløv 1*, M. Brock Fenton 1 and John M. Ratcliffe 2 1 Department of Biology, Western University, London, ON, Canada 2 Institute of Biology, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark Edited by: The discovery of ultrasonic bat echolocation prompted a wide search for other animal Mariana L. Melcón, Fundación biosonar systems, which yielded, among few others, two avian groups. One, the South Cethus, Argentina American Oilbird (Steatornis caripensis: Caprimulgiformes), is nocturnal and eats fruit. The Reviewed by: other is a selection of diurnal, insect-eating swiftlets (species in the genera Aerodramus Noritaka Ichinohe, National Institute of Neuroscience, Japan and Collocalia:Apodidae)fromacrosstheIndo-Pacific.Birdecholocationisrestrictedto Lore Thaler, Durham University, UK lower frequencies audible to humans, implying a system of poorer resolution than the *Correspondence: ultrasonic (>20 kHz) biosonar of most bats and toothed whales. As such, bird echolocation Signe Brinkløv, Department of has been labeled crude or rudimentary. Yet, echolocation is found in at least 16 extant Biology, Western University, bird species and has evolved several times in avian lineages. Birds use their syringes to 1151 Richmond Street, London, ON N6A 3K7, Canada. produce broadband click-type biosonar signals that allow them to nest in dark caves and e-mail: [email protected] tunnels, probably with less predation pressure. There are ongoing discrepancies about several details of bird echolocation, from signal design to the question about whether echolocation is used during foraging. It remains to be seen if bird echolocation is as sophisticated as that of tongue-clicking rousette bats. -

The Asean Heritage Parks Are Educational and Inspiratio

Factsheet : Asean Heritage Parks Overview of Asean Heritage Parks (AHPs) The Asean Heritage Parks are educational and inspirational sites of high conservation importance , preserving a complete spectrum of representative ecosystems of the Asean region. These parks embody the aspirations of the people of the ten Asean nations to conserve their natural treasures. It was established to generate greater awareness, pride, appreciation, enjoyment and conservation of the Asean region’s rich natural heritage through a regional network of representative protected areas. A designation as an AHP is both an honour and a responsibility. The country accepts the responsibility to ensure the best possible level of protection is afforded to the site. The Asean Declaration on Heritage Parks In December 2003 at Yangon, all the Ministers of Environment of Asean member states accepted the principles of Asean Heritage Parks (AHPs) and jointly agreed to participate within the AHPs program to establish, develop and protect the designated parks. The 2003 declaration constitutes a reiteration of an earlier agreement in 1884, initiated by a smaller Asean. This declaration underscores the common cooperation between member states for the development and implementation of regional conservation and management action plans. Criteria for Nomination/ Award: Criteria Description Ecological An intact ecological process and capability to regenerate with completeness minimal human intervention. Representativeness The variety of ecosystems or species typical of a particular region. Naturalness In natural condition such as a second-growth forest or a rescued coral reef formation, with natural processes still going on. High conservation Has global significance for the conservation of important or importance valuable species, ecosystems or genetic resources; evokes respect for nature when people see it, as well as feeling of loss when its natural condition is lost. -

Sarawak—A Neglected Birding Destination in Malaysia RONALD ORENSTEIN, ANTHONY WONG, NAZERI ABGHANI, DAVID BAKEWELL, JAMES EATON, YEO SIEW TECK & YONG DING LI

30 BirdingASIA 13 (2010): 30–41 LITTLE-KNOWN AREA Sarawak—a neglected birding destination in Malaysia RONALD ORENSTEIN, ANTHONY WONG, NAZERI ABGHANI, DAVID BAKEWELL, JAMES EATON, YEO SIEW TECK & YONG DING LI Introduction It is our hope that this article will be a catalyst One of the ironies of birding in Asia is that despite for change. Alhough much of Sarawak has been the fact that Malaysia is one of the most popular logged and developed, the state still contains destinations for birdwatchers visiting the region, extensive tracts of rainforest habitat; it is still one very few visit the largest state in the country. of the least developed states in Malaysia once away Peninsular Malaysia, and the state of Sabah in east from the four main coastal cities. Given its extensive Malaysia, are well-known and are visited several coastline, Sarawak contains excellent wintering times a year by international bird tour operators grounds for waders and other waterbirds. BirdLife as well as by many independent birdwatchers. But International has designated 22 Important Bird Areas Malaysia’s largest state, Sarawak, which sits (IBAs) in Sarawak, the highest number for any state between the two and occupies one fifth of eastern in Malaysia and more than in all the states of west Borneo, is unfortunately often overlooked by Malaysia combined (18), whilst Sabah has 15 IBAs birdwatchers. The lack of attention given to (Yeap et al. 2007). Sarawak is not only a loss for birders, but also to the state, as the revenue that overseas birdwatchers Why do birders neglect Sarawak? bring in can be a powerful stimulus for protecting That Sarawak is neglected is clear from an examination forests, wetlands and other important bird habitats. -

Title Bako National Park

Title Bako National Park - A natural laboratory for teaching and learning about the environment Author(s) Yee, Sze Onn & Chin, Long Fay Source Teaching and Learning, 9(2),82-101 Published by Institute of Education (Singapore) This document may be used for private study or research purpose only. This document or any part of it may not be duplicated and/or distributed without permission of the copyright owner. The Singapore Copyright Act applies to the use of this document. Bako National Park - A Natural Laboratory For Teaching And Learning About The Environment YEE SZE ONN AND CHIN LONG FAY Introduction National parks are an important form of landuse. They aim at conserving, protecting and preserving the flora, fauna, landscape and scientifically interesting features as well as providing a laboratory for teaching and learning. Bako National Park occupies 2742 hectares of a rugged sandstone peninsula in the south western region of Sarawak. The park is dominated by a sandstone plateau which averages about 100 metres above sea level. Denundation by water over long periods of time has sculptured this plateau into a distinctive landscape which offers excellent opportunities for field studies in geography and science. Plate 1. A partial view of Bako National Park, Sarawak. Bako National Park 83 Location and Accessibility Bako National Park is easily accessible. It is only one and a half hours by air from Singapore. The park is approximately 37 km from Kuching. The newly built Kuching-Bako road provides fast and easy access by land to Kg. Bako from where the park is reached after a 25-minute boat trip.