South African Civil Defence Organisation and Administration with Particular Reference to the Cape Peninsula

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AG1977-A5-63-1-001-Jpeg.Pdf

/\ S. G J 24 September 1991 updated 19 November 1991 17 December 1991 13 January 1992 " 28 January 1992 Some figures obtained from conscripts on people not reporting for camps and national service: Transvaal Light Horse (artillery) 600 called up 150 came Sandton Commando (Aug 91) 320 called up 32 came (90 had applied for and got deferment) Randburg Commando, July 91 300 called up 20 came Wemmer Pan Commando (60 day camp, 220 called up 28 came Aug-Oct 91) National service, July, Nasrec Only 50% reported National service, July, Medical Only 37% reported National service, July, Personnel Only 17% reported National service, July, Potchefstroom 600 called up, 200 came Luatla military exercise, October 91 7000 called up, 3000 came Univ of Pta unit, Camp, Natal Dec ’91 750 called up, 73reported Rand Light Infantry, Camp, Ellis Ras 1200 “ " 200 December ’91 and Jan ’92 RLI, Parade, October ’91 About 50% reported National service, July 91, countrywide 27000 called up, 20000 reported (=74%) Voortrekkerhoogte, National service 800 called up over 3 January 1992 days, 51 reported on 6/1 Univ of OFS commando, camp Dec 91/Jan 230 called up, 40 came Doornkop camp, September 91 230 called up, 30 came Parade at Meyerton command, ? 300 called up, 30 came Braamfontein medical unit 120 called up,20 came Reg Pres Kruger Randfontein 970 called up, 250 came 24 September 1991 updated 19 November 1991 17 December 1991 13 January 1992 Some figures obtained from conscripts on people not reporting for camps and national service: Transvaal Light Horse (artillery) -

Wooltru Healthcare Fund Optical Network List Gauteng

WOOLTRU HEALTHCARE FUND OPTICAL NETWORK LIST GAUTENG PRACTICE TELEPHONE AREA PRACTICE NAME PHYSICAL ADDRESS CITY OR TOWN NUMBER NUMBER ACTONVILLE 456640 JHETAM N - ACTONVILLE 1539 MAYET DRIVE ACTONVILLE 084 6729235 AKASIA 7033583 MAKGOTLOE SHOP C4 ROSSLYN PLAZA, DE WAAL STREET, ROSSLYN AKASIA 012 5413228 AKASIA 7025653 MNISI SHOP 5, ROSSLYN WEG, ROSSLYN AKASIA 012 5410424 AKASIA 668796 MALOPE SHOP 30B STATION SQUARE, WINTERNEST PHARMACY DAAN DE WET, CLARINA AKASIA 012 7722730 AKASIA 478490 BODENSTEIN SHOP 4 NORTHDALE SHOPPING, CENTRE GRAFENHIEM STREET, NINAPARK AKASIA 012 5421606 AKASIA 456144 BODENSTEIN SHOP 4 NORTHDALE SHOPPING, CENTRE GRAFENHIEM STREET, NINAPARK AKASIA 012 5421606 AKASIA 320234 VON ABO & LABUSCHAGNE SHOP 10 KARENPARK CROSSING, CNR HEINRICH & MADELIEF AVENUE, KARENPARK AKASIA 012 5492305 AKASIA 225096 BALOYI P O J - MABOPANE SHOP 13 NINA SQUARE, GRAFENHEIM STREET, NINAPARK AKASIA 087 8082779 ALBERTON 7031777 GLUCKMAN SHOP 31 NEWMARKET MALL CNR, SWARTKOPPIES & HEIDELBERG ROAD, ALBERTON ALBERTON 011 9072102 ALBERTON 7023995 LYDIA PIETERSE OPTOMETRIST 228 2ND AVENUE, VERWOERDPARK ALBERTON 011 9026687 ALBERTON 7024800 JUDELSON ALBERTON MALL, 23 VOORTREKKER ROAD, ALBERTON ALBERTON 011 9078780 ALBERTON 7017936 ROOS 2 DANIE THERON STREET, ALBERANTE ALBERTON 011 8690056 ALBERTON 7019297 VERSTER $ VOSTER OPTOM INC SHOP 5A JACQUELINE MALL, 1 VENTER STREET, RANDHART ALBERTON 011 8646832 ALBERTON 7012195 VARTY 61 CLINTON ROAD, NEW REDRUTH ALBERTON 011 9079019 ALBERTON 7008384 GLUCKMAN 26 VOORTREKKER STREET ALBERTON 011 9078745 -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

Cultural Heritage Regeneration of District Six: a Creative Tourism Approach

CULTURAL HERITAGE REGENERATION OF DISTRICT SIX: A CREATIVE TOURISM APPROACH by SIRHAN JESSA Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Technology: Tourism and Hospitality Management in the Faculty of Business and Management Sciences at the Cape Peninsula University of Technology Supervisor: Professor J N Steyn Co-supervisor: Professor J P Spencer Cape Town March 2015 CPUT copyright information The dissertation/thesis may not be published either in part (in scholarly, scientific or technical journals), or as a whole (as a monograph), unless permission has been obtained from the University. DECLARATION I, the undersigned, hereby declare that this dissertation is my own work, that all sources used and quoted have been cited and acknowledged by means of complete references and that this dissertation was not previously submitted to any other university or university of technology for degree purposes. _________________________ _________________________ Sirhan Jessa Date: 1 March 2015 i CONFIRMATION OF PROOFREADING 8 Briar Close Silverglade Fish Hoek 7975 [email protected] 24.04.2014 To whom it may concern: I have proofread and edited the thesis: Cultural heritage regeneration in District Six: A creative tourism approach by Sirhan Jessa, a dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Technologiae (Travel and Events Management) in the Faculty of Business at the Cape Peninsula University of Technology. Suggested corrections and/or alterations have been affected. Rolfe Proske ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS All praise be to God. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisors Professors J.N. Steyn and J.P. Spencer for their guidance, support and encouragement during the course of this research project. -

Download the Paper (Pdf)

These are dresses that are stitched with dreams: Struggle, Freedom and the Women of the Clothing and Textile Industry of the Western Cape Siona O’Connell Abstract The ordinary archive of the racially oppressed in South Africa offers a critical lens through which to interrogate notions of resistance, subjectivities and freedom. This paper considers these questions by examining the phenomenon that is the annual Spring Queen pageant which, for more than 46 years, has proffered a potential real-life ‘Cinderella’ experience to the poorly-paid, industrious women of the Western Cape’s clothing and textile trade. Initiated by their union, the Southern African Clothing and Textile Workers’ Union (SACTWU) in the late 1970s as a response to worker agitation, the social significance of the pageant runs incontrovertibly deeper than a one-night spectacle. Despite a dearth of subject-specific formal research, this paper draws on available literature analysing the impact of apartheid on culture and society in South Africa, along with extensive relevant media coverage of the Spring Queen pageant, and personal interviews with those involved and impacted. It goes beyond describing the experiences of working class ‘coloured’ women who contributed to the anti-apartheid struggle through their union activities. It also highlights how an enduring annual gala event has afforded the ‘invisible’ clothing production line workers who underpin a multi-billion rand South African export industry an opportunity to envision a yet-to-be realised freedom, while reflecting the power and resilience of the ordinary to transform in extraordinary times. Keywords: Spring Queen, clothing and textile industry, Cape Town, pageant, Southern African Clothing and Textile Workers’ Union (SACTWU), apart- heid, freedom, labour Alternation Special Edition 26 (2019) 98 – 121 98 Print ISSN 1023-1757; Electronic ISSN: 2519-5476; DOI https://doi.org/10.29086/2519-5476/2019/sp26a4 Struggle, Freedom and the Women of the Clothing and Textile Industry Working in a factory is not a very glamorous job. -

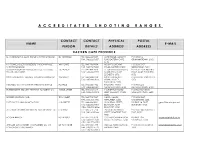

Accreditated Shooting Ranges

A C C R E D I T A T E D S H O O T I N G R A N G E S CONTACT CONTACT PHYSICAL POSTAL NAME E-MAIL PERSON DETAILS ADDRESS ADDRESS EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE D J SURRIDGE T/A ALOE RIDGE SHOOTING RANGE DJ SURRIDGE TEL: 046 622 9687 ALOE RIDGE MANLEY'S P O BOX 12, FAX: 046 622 9687 FLAT, EASTERN CAPE, GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 6140 K V PEINKE (SOLE PROPRIETOR) T/A BONNYVALE WK PEINKE TEL: 043 736 9334 MOUNT COKE KWT P O BOX 5157, SHOOTING RANGE FAX: 043 736 9688 ROAD, EASTERN CAPE GREENFIELDS, 5201 TOMMY BOSCH AND ASSOCIATES CC T/A LOCK, T C BOSCH TEL: 041 484 7818 51 GRAHAMSTAD ROAD, P O BOX 2564, NOORD STOCK AND BARREL FAX: 041 484 7719 NORTH END, PORT EINDE, PORT ELIZABETH, ELIZABETH, 6056 6056 SWALLOW KRANTZ FIREARM TRAINING CENTRE CC WH SCOTT TEL: 045 848 0104 SWALLOW KRANTZ P O BOX 80, TARKASTAD, FAX: 045 848 0103 SPRING VALLEY, 5370 TARKASTAD, 5370 MECHLEC CC T/A OUTSPAN SHOOTING RANGE PL BAILIE TEL: 046 636 1442 BALCRAIG FARM, P O BOX 223, FAX: 046 636 1442 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 BUTTERWORTH SECURITY TRAINING ACADEMY CC WB DE JAGER TEL: 043 642 1614 146 BUFFALO ROAD, P O BOX 867, KING FAX: 043 642 3313 KING WILLIAM'S TOWN, WILLIAM'S TOWN, 5600 5600 BORDER HUNTING CLUB TE SCHMIDT TEL: 043 703 7847 NAVEL VALLEY, P O BOX 3047, FAX: 043 703 7905 NEWLANDS, 5206 CAMBRIDGE, 5206 EAST CAPE PLAINS GAME SAFARIS J G GREEFF TEL: 046 684 0801 20 DURBAN STREET, PO BOX 16, FORT [email protected] FAX: 046 684 0801 BEAUFORT, FORT BEAUFORT, 5720 CELL: 082 925 4526 BEAUFORT, 5720 ALL ARMS FIREARM ASSESSMENT AND TRAINING CC F MARAIS TEL: 082 571 5714 -

Vietnam War Turning Back the Clock 93 Year Old Arctic Convoy Veteran Visits Russian Ship

Military Despatches Vol 33 March 2020 Myths and misconceptions Things we still get wrong about the Vietnam War Turning back the clock 93 year old Arctic Convoy veteran visits Russian ship Battle of Ia Drang First battle between the Americans and NVA For the military enthusiast CONTENTS March 2020 Click on any video below to view How much do you know about movie theme songs? Take our quiz and find out. Hipe’s Wouter de The old South African Page 14 Goede interviews former Defence Force used 28’s gang boss David a mixture of English, South Vietnamese Williams. Afrikaans, slang and techno-speak that few Special Forces outside the military could hope to under- stand. Some of the terms Features 32 were humorous, some Weapons and equipment were clever, while others 6 We look at some of the uniforms were downright crude. Ten myths about Vietnam and equipment used by the US Marine Corps in Vietnam dur- Although it ended almost 45 ing the 1960s years ago, there are still many Part of Hipe’s “On the myths and misconceptions 34 couch” series, this is an about the Vietnam War. We A matter of survival 26 interview with one of look at ten myths and miscon- This month we look at fish and author Herman Charles ceptions. ‘Mad Mike’ dies aged 100 fishing for survival. Bosman’s most famous 20 Michael “Mad Mike” Hoare, characters, Oom Schalk widely considered one of the 30 Turning back the clock Ranks Lourens. Hipe spent time in world’s best known mercenary, A taxi driver was shot When the Russian missile cruis- has died aged 100. -

Kaplan Auctions 115 Dunottar Street, Sydenham, 2192, Johannesburg Po Box 28913, Sandringham, 2131, R.S.A

KAPLAN AUCTIONS 115 DUNOTTAR STREET, SYDENHAM, 2192, JOHANNESBURG PO BOX 28913, SANDRINGHAM, 2131, R.S.A. TEL: +27 11 640 6325 / 485 2195 FAX: +27 11 640 3427 E-MAIL ADDRESS: [email protected] and [email protected] Please insist on a reply. WEBSITE ADDRESS: www.aleckaplan.co.za AUCTION B95 SALE OF MEDALS, BADGES , MILITARIA TH 19 JUNE 2019 TO BE HELD 6pm AT OUR PREMISES PLEASE NOTE: ALL THE ITEMS MAY BE VIEWED ON OUR WEBSITE: www.aleckaplan.co.za 115 DUNOTTAR STREET, SYDENHAM, 2192 JOHANNESBURG THE LOTS WILL BE ON VIEW AT OUR PREMISES –ONLY BY APPOINTMENT. BIDDING PROCEDURE NO BIDS WILL BE ACCEPTED AFTER 12 NOON ON DAY OF AUCTION NO BIDS WILL BE PLACED WITHOUT COPY OF IDENTITY DOCUMENT 1. The Auctioneer’s decision is final. 2. Please ensure that you quote the correct lot number when bidding by post. Mistakes will not be corrected after the sale. 3. This is a live auction and bids may be submitted in writing by, letter, e-mail or by telephone for those who cannot attend in person. 4. All items will be sold to the highest bidder. 5. Reserves have been fixed by the seller but should a reserve, in the opinion of a possible buyer be too high, I will be pleased to submit a reasonable offer to the seller, should the lot otherwise be unsold. 6. Lots have been carefully graded. Should anyone not be satisfied with the grading, such an item may be returned to us within 7 days of receipt thereof. -

AG1977-A11-5-1-001-Jpeg.Pdf

END CONSCRIPTION COMMITTEE P. 0. B O X 208 WOODSTOCK 7915 SOUTH AFRICA 26 February 1985 Dear Friend The End Conscription Committee (E.C.C.) is a broad front of organisations which have come together to oppose compulsory conscription into the South African Defence Force. The campaign is being waged nationally and aims to raise awareness of the militarisation of our society and to unite and mobilise as broad a sector of the population as possible. A brief history of the campaign is enclosed. Young people are most directly affected by conscription. They are often antagonistic to the S. A. D. F. and its role in defending Apartheid. They are therefore potentially open to the message of E.C.C. E.C.C. has decided to prioritise the International Youth Year campaign in 1985. In particular it is aiming to give a strong anti-conscription content to the npeacen theme. E.C.C. is taking up the I.Y.Y. campaign in two ways: firstly, through the organisation of the youth constituency against conscription and secondly, by participating in other I.Y.Y. structures. Presently E.C.C. is represented on the I.Y.Y. committees of both the United Democratic Front and the South African Council of Churches. The Western Cape E. C. C.'s plans for Youth Year are enclosed. We would greatly appreciate any assistance you might give us, in particular any resources. Anything received from you will be circulated to our branches in Johannesburg and Durban. We are also currently trying to raise finances through overseas agencies. -

National Liquor Authority Register

NATIONAL LIQUOR AUTHORITY REGISTER - 30 JUNE 2013 Registration Registered Person Trading Name Activities Registered Person's Principal Place Of Business Province Date of Transfer & (or) Date of Number Permitted Registration Relocations Cancellation RG 0006 The South African Breweries Limited Sab -(Gauteng) M & D 3 Fransen Str, Chamber GP 2005/02/24 N/A N/A RG 0007 Greytown Liquor Distributors Greytown Liquor Distributors D Lot 813, Greytown, Durban KZN 2005/02/25 N/A N/A RG 0008 Expo Liquor Limited Expo Liquor Limited (Groblersdal) D 16 Linbri Avenue, Groblersdal, 0470 MPU N/A 28/01/2011 RG 0009 Expo Liquor Limited Expo Liquor Limited (Ga D Stand 14, South Street, Ga-Rankuwa, 0208 NW N/A 27/09/2011 Rankuwa) RG 0010 The South African Breweries Limited Sab (Port Elizabeth) M & D 47 Kohler Str, Perseverence, Port Elizabeth EC 2005/02/24 N/A N/A RG 0011 Lutzville Vineyards Ko-Op Ltd Lutzville Vineyards Ko-Op Ltd M & D Erf 312 Kuils River, Pinotage Str, WC 2008/02/20 N/A N/A Saxenburg Park, Kuils River RG 0012 Louis Trichardt Beer Wholesalers (Pty) Louis Trichardt Beer Wholesalers D Erf 05-04260, Byles Street, Industrial Area, LMP 2005/06/05 N/A N/A Ltd Louis Trichardt, Western Cape RG 0013 The South African Breweries Limited Sab ( Newlands) M & D 3 Main Road, Newlands WC 2005/02/24 N/A N/A RG 0014 Expo Liquor Limited Expo Liquor Limited (Rustenburg) D Erf 1833, Cnr Ridder & Bosch Str, NW 2007/10/19 02/03/2011 Rustenburg RG 0015 Madadeni Beer Wholesalers (Pty) Ltd Madadeni Beer Wholesalers (Pty) D Lot 4751 Section 7, Madadeni, Newcastle, KZN -

Cape Town Rd R L N W Or T

Legend yS Radisson SAS 4 C.P.U.T. u# D S (Granger Bay Campus) H R u Non-Perennial River r Freeway / National Road R C P A r E !z E l e T Mouille Point o B . Granger Bay ast y A t Perennial River h B P l Village E Yacht Club e Through Route &v e A d ie x u# s Granger r a Ü C R P M R a H nt n d H . r l . R y hN a e d y d u# Ba G Bay L i % Railway with Station r R ra r P E P The Table Minor Road a D n te st a Table Bay Harbour l g a a 7 La Splendina . e s N R r B w Bay E y t ay MetropolitanO a ak a P Water 24 R110 Route Markers K han W y re u i n1 à î d ie J Step Rd B r: u# e R w Q r ie Kings Victoria J Park / Sports Ground y t W 8} e a L GREEN POINT Wharf 6 tt B a. Fort Wynyard Warehouse y y Victoria Built-up Area H St BMW a E K J Green Point STADIUM r 2 Retail Area Uà ge Theatre Pavillion r: 5 u lb Rd an y Q Basin o K Common Gr @ The |5 J w Industrial Area Pavillion!C Waterfront ua e Service Station B Greenpoint tt çc i F Green Point ~; Q y V & A WATERFRONT Three Anchor Bay ll F r: d P ri o /z 1 R /z Hospital / Clinic with Casualty e t r CHC Red Shed ÑG t z t MARINA m u# Hotel e H d S Cape W Somerset Quay 4 r r y Craft A s R o n 1x D i 8} n y th z Hospital / Clinic le n Medical a Hospital Warehouse u 0 r r ty m Green Point Club . -

Defence Dangerous Object

work within the system could be defined as a national key point, Mr Myburgh said.4 In May the Control of Access to Public Premises and Vehicles Act of 1985 was gazetted by the state president.' It granted the owners of public premises or vehicles wide powers for the safeguarding of those premises and vehicles. A person authorised by the owner of any public premises or public vehicle may, for SECURITY instance, require of a person who wants to enter such premises or vehicle that he/she subject himself/herself, or anything in his/her possession to an examination by an electronic or other apparatus in order to determine the presence of any Defence dangerous object. In terms of the act. powers of search and the authority to demand identification are given. The only qualification was that physical searches In November the minister of defence, Mr Magnus Malan, was handed the report of women be done by women. of the committee of inquiry set up in May 1984 under the chairmanship of the chicf On 13 December the state president, Mr P W Botha, amended the general of the army, Lieutenant General Jannie Geidenhuys, to investigate the South regulations promulgated under the Defence Act of 1957 by the addition of a new African Defence Force (SADF) and related aspects affecting the Armaments chapter to increase the powers of the South African Defence Force (SADF) in Corporation of South Africa (ARMSCOR) in the context of the economic situations of internal unrest. Regulation 1 provided that the SADF might be used situation and the future needs of the country (the Geidenhuys committee).