Timbuktu Food Security Program – TFSI/MYAP)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rapport Annuel 2016 Etat D'execution Des Activites

MINISTERE DE L’ENVIRONNEMENT DE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI L’ASSAINISSEMENT ET DU ****************** DEVELOPPEMENT DURABLE ************* Un Peuple –Un But – Une Foi AGENCE DE L’ENVIRONNEMENT ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT DURABLE (AEDD) ************* PROGRAMME D’APPUI A L’ADAPTATION AUX CHANGEMENTS CLIMATIQUES DANS LES COMMUNES LES PLUS VULNERABLES DES REGIONS DE MOPTI ET DE TOMBOUCTOU (PACV-MT) RAPPORT ANNUEL 2016 PACV-MT ETAT D’EXECUTION DES ACTIVITES Octobre 2016 ACRONYMES AEDD : Agence de l’Environnement et du Développement Durable AFB : Fonds d’Adaptation CCOCSAD : Comité Communale d’Orientation, de Coordination et de Suivi des Actions de Développement CLOCSAD : Comité Local d’Orientation, de Coordination et de Suivi des Actions de Développement CROCSAGD : Comité Régionale d’Orientation, de Coordination et de Suivi des Actions de Gouvernance et de Développement CEPA : Champs Ecoles Paysans Agroforestiers CEP : Champs Ecoles Paysans CNUCC : Convention Cadre des Nations Unies sur le Changement Climatique DAO : Dossier d’Appel d’Offres DCM : Direction de la Coopération Multilatérale DGMP : Direction Générale des Marchés Publics MINUSMA : Mission Multidimensionnelle Intégrée des Nations Unies pour la Stabilisation au Mali OMVF : Office pour le Mise en Valeur du système Faguibine PAM : Programme Alimentaire Mondial PDESC : Plan de développement Economique, Social et Culturel PTBA : Plan de Travail et de Budget Annuel PACV-MT : Programme d‘Appui à l‘Adaptation aux Changements Climatiques dans les Communes les plus Vulnérables des Régions de Mopti et de Tombouctou PK : Protocole de Kyoto PNUD : Programme des Nations Unies pour le Développement TDR : Termes de références UGP : Unité de Gestion du Programme RAPPORT ANNUEL 2016 DU PACV-MT Page 2 sur 47 TABLE DES MATIERES ACRONYMES ............................................................................................................... -

Peacebuilding Fund

Highlights #13 | February 2016 First Annual Conference on the Regional Monthly Bulletin Development Agencies Peacebuilding Fund: PBSO mission to Mali Trust Fund: new equipment for the Ministry Role of the S&R Section of Security and Civil Protection Mopti: socio-economic integration of In support to the Deputy Special Representative Through this monthly bulletin, we provide regular handicapped persons (QIP) of the Secretary-General (DSRSG), Resident updates on stabilization & recovery developments Gao: 4 streets with solar public lightning; 3 Coordinator (RC) and Humanitarian Coordinator (HC) and activities in the north of Mali. The intended new literacy classrooms (QIPs) in her responsibilities to lead the United Nations’ audience is the section’s main partners including Timbuktu: Municipal Stadium documentary (QIP) contribution to Mali’s reconstruction efforts, the MINUSMA military and civilian components, UNCT More QIPs launched in northern regions Stabilization & Recovery section (S&R) promotes and international partners. synergies between MINUSMA, the UN Country Team and other international partners. For more information: Main Figures Gabriel Gelin, Information Specialist (S&R QIPs 2015-2016: 46 projects with 10 completed section) - [email protected] and 36 under implementation over a total budget of 4 million USD (155 projects since 2013) Donor Coordination and Partnerships Peacebuilding Fund (PBF): 5 projects started in 2015 over 18 months for a total budget of On 1st of February, S&R met with officials On 4th of February, was held a political 10,932,168 USD 1. of the Ministry of Decentralization 2. meeting of the CRZPC (Commission Trust Fund (TF): 8 projects completed/nearing and State Reform to establish partnership Réhabilitation des Zones Post-Conflitt) at the finalization and 12 projects under implementation relations. -

Bulletin Sap N°377

PRESIDENCE DE LA REPUBLIQUE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI ------------***------------ ------------***------------ COMMISSARIAT A LA SECURITE ALIMENTAIRE Un Peuple-Un But-Une Foi ------------***------------ SYSTEME D’ALERTE PRECOCE (S.A.P) BP. 2660, Bamako-Mali Tel :(223) 20 80 10 28 ; Adresse email : [email protected] /[email protected] Adresse Site Web : www.sapmali.com BULLETIN SAP N°377 Mars 2019 Présentation du Système d’Alerte Précoce (S.A.P) du MALI PRESENTATION DU SAP Le SAP est un système de collecte permanente d’informations sur la situation alimentaire. Sa mission consiste essentiellement à fournir à l’ensemble du système de sécurité alimentaire du pays les informations nécessaires à une affectation optimale du stock national de sécurité dans le cadre d'opérations d'aides alimentaires ciblées ou à une utilisation efficiente des fonds de sécurité alimentaire dans des actions d’atténuation d’insécurité alimentaire. Son objectif est de déterminer suffisamment à l'avance les populations les plus vulnérables risquant de connaître des difficultés alimentaires et/ou nutritionnelles, de dire les raisons du risque, de dire à partir de quand, pour combien de temps, avec quelle intensité et quelles sont les actions d’atténuation possibles. Les informations sont recueillies auprès des services administratifs, techniques, de la société civile et des élus locaux depuis les communes vers les chefs-lieux de cercles, les chefs-lieux de Régions et enfin Bamako. Au niveau de chaque chef-lieu de Région, l'équipe régionale SAP chargée du recueil des informations est appuyée par la Direction Régionale de la Planification, de la Statistique, de l’Informatique, de l’Aménagement du Territoire et de la Population. -

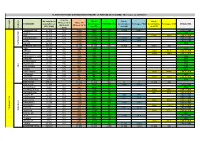

R E GION S C E R C L E COMMUNES No. Total De La Population En 2015

PLANIFICATION DES DISTRIBUTIONS PENDANT LA PERIODE DE SOUDURE - Mise à jour au 26/05/2015 - % du CH No. total de la Nb de Nb de Nb de Phases 3 à 5 Cibles CH COMMUNES population en bénéficiaires TONNAGE CSA bénéficiaires Tonnages PAM bénéficiaires Tonnages CICR MODALITES (Avril-Aout (Phases 3 à 5) 2015 (SAP) du CSA du PAM du CICR CERCLE REGIONS 2015) TOMBOUCTOU 67 032 12% 8 044 8 044 217 10 055 699,8 CSA + PAM ALAFIA 15 844 12% 1 901 1 901 51 CSA BER 23 273 12% 2 793 2 793 76 6 982 387,5 CSA + CICR BOUREM-INALY 14 239 12% 1 709 1 709 46 2 438 169,7 CSA + PAM LAFIA 9 514 12% 1 142 1 142 31 1 427 99,3 CSA + PAM SALAM 26 335 12% 3 160 3 160 85 CSA TOMBOUCTOU TOMBOUCTOU TOTAL 156 237 18 748 18 749 506 13 920 969 6 982 388 DIRE 24 954 10% 2 495 2 495 67 CSA ARHAM 3 459 10% 346 346 9 1 660 92,1 CSA + CICR BINGA 6 276 10% 628 628 17 2 699 149,8 CSA + CICR BOUREM SIDI AMAR 10 497 10% 1 050 1 050 28 CSA DANGHA 15 835 10% 1 584 1 584 43 CSA GARBAKOIRA 6 934 10% 693 693 19 CSA HAIBONGO 17 494 10% 1 749 1 749 47 CSA DIRE KIRCHAMBA 5 055 10% 506 506 14 CSA KONDI 3 744 10% 374 374 10 CSA SAREYAMOU 20 794 10% 2 079 2 079 56 9 149 507,8 CSA + CICR TIENKOUR 8 009 10% 801 801 22 CSA TINDIRMA 7 948 10% 795 795 21 2 782 154,4 CSA + CICR TINGUEREGUIF 3 560 10% 356 356 10 CSA DIRE TOTAL 134 559 13 456 13 456 363 0 0 16 290 904 GOUNDAM 15 444 15% 2 317 9 002 243 3 907 271,9 CSA + PAM ALZOUNOUB 5 493 15% 824 3 202 87 CSA BINTAGOUNGOU 10 200 15% 1 530 5 946 161 4 080 226,4 CSA + CICR ADARMALANE 1 172 15% 176 683 18 469 26,0 CSA + CICR DOUEKIRE 22 203 15% 3 330 -

Annuaire Statistique 2015 Du Secteur Développement Rural

MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI ----------------- Un Peuple - Un But – Une Foi SECRETARIAT GENERAL ----------------- ----------------- CELLULE DE PLANIFICATION ET DE STATISTIQUE / SECTEUR DEVELOPPEMENT RURAL Annuaire Statistique 2015 du Secteur Développement Rural Juin 2016 1 LISTE DES TABLEAUX Tableau 1 : Répartition de la population par région selon le genre en 2015 ............................................................ 10 Tableau 2 : Population agricole par région selon le genre en 2015 ........................................................................ 10 Tableau 3 : Répartition de la Population agricole selon la situation de résidence par région en 2015 .............. 10 Tableau 4 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par sexe en 2015 ................................. 11 Tableau 5 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par Région en 2015 ...................................... 11 Tableau 6 : Population agricole par tranche d'âge et selon la situation de résidence en 2015 ............. 12 Tableau 7 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 ..................................................... 15 Tableau 8 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 (suite) ................................... 16 Tableau 9 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par mois 2015 ........................................................................................ 17 Tableau 10 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par station en 2015 et sa comparaison à -

Infected Areas As Oa 17 April 1986 — Zones Infectées Au 17 Avril 1986

WX/i bpidem HiX No, lo - lô Aprü J^fiC - 123 - Reieveepule ni fieod Nw lt> - IS avnl iys6 Infected Areas as oa 17 April 1986 — Zones infectées au 17 avril 1986 For criteria used in compiling this Usu see No 2, page 10 - Les critères appliques pour la compilation de celle liste sont publies dans le Nü 2, page 10. X Newly reported areas - Nouvelles zones signalées. PLAGUE - PESTE lluancabamba Province RUANDA Aceh Tenggara Regency Aceh Timur Regency Africa — Afrique C de la Froment Disinct Gtsenyi Region Hiuncabamba Disinct Aceh Utara (P) Regency MADAGASCAR SENEGAL - SÉNÉGAL Banda Aceh Municipality Piura Province Cap-lert Region Antananarivo Province Las Lomas Disinct Pidie Regency Antsirabe U S Pré/ Dakar Jaw a Barat Province Manandona District Asia - Asie Fleuve Region Cirebon Regency Vtnaninkarena District v ie t n a m Dagana Depanement Purwakarta Regency Soavinandrtana S Préf Gia-Lai-Cong Turn Province Stne-Saioum Region Serang Regency Ambaioasana Centre Lim Dông Province Fauck Depanement Sumedang Regency Fianaranisoa Province Phu Kiunh Province Kaoluck Département Jawa Tengah Province imbatujinandrahana S. Préf Thies Region Banjamegara Regency Arobatomifasoniira Disinct Thies Depanement Banyumas Regency Soawna District SIERRA LEONE Brebes Regency Ambohimahasoa S Préf CHOLERA - CHOLERA North West Area Cilacap Regency Manandroy District Africa - .Afrique Kambm Distnct Demak Regency Ambosilra S, Pré) BENIN - BÉNIN Pon Loko Distnct Jeparu Regency Ambaiomamu Disinct Tonkohli District PekaJongan Regency Ambohimahazo Disinct Allantique Prounce -

0 16 32 48 64 8 Km

LOCALISATIONREGIONS REALISATIONS DE TOMBOUCTOU RELAC I & ET II / TOMBOUCTOUTAOUDENIT LOCALISATION REALISATION PROJETS RELAC I ET II Projet MLI/803 Relance de l’Economie locale et Appui aux Collectivités dans le Nord du Mali Avec la participation financière de l’UE ¯ REPUBLIQUE DU MALI SALAM C.TOMBOUCTOU BER TICHIFT DOUAYA INASTEL ELB ESBAT LYNCHA BER AIN RAHMA TINAKAWAT TAWAL C.BOUREM AGOUNI C.GOUNDAM ZARHO JIDID LIKRAKAR GABERI ATILA NIBKIT JAMAA TINTÉLOUT RHAROUS ERINTEDJEFT BER WAIKOUNGOU NANA BOUREM INALY DANGOUMA ALAFIA ALGABASTANE KEL ESSOUK TOBORAK NIKBKIT KAIDAM KEL ESSOUK ABOUA BENGUEL RHAROUS TOMBOUCTOU RHAROUS CAP ARAOUNE BOUGOUNI TINDIAMBANE TEHERDJE MINKIRI MILALA CT TOUEDNI IKOUMADEN DOUDARE BÉRÉGOUNGOU EMENEFAD HAMZAKOMA MORA TEDEYNI KEL INACHARIADJANDJINA KOIRA KABARA TERDIT NIBKITE KAIDAM ADIASSOU ARNASSEYEBELLESAO ZEINA DOUEKIRE NIBKIT KORIOME BOUREM INALY BORI KEL IKIKANE TIMBOUSE KELTIROU HOUNDOUBOMO TAGLIF INKARAN KAGA TOYA HEWA TILIMEDESS I INDALA ILOA KOULOUTAN II KELTAMOULEIT BT KEL ANTASSAR DJEGUELILA TASSAKANE IDJITANE ISSAFEYE DONGHOI TAKOUMBAOUT EDJAME ADINA KOIRA AGLAL DOUEKIRE KESSOU BIBI LAFIA NIAMBOURGOU HAMZAKONA ZINZIN 3 BOYA BABAGA AMTAGARE KATOUWA WANA KEL HARODJENE 2 FOUYA GOUNDAM DOUKOURIA KESSOU KOREY INTEDEINI EBAGAOU KEYNAEBAGAOU BERRI BORA CAMP PEUL GOYA SUD GARI KEL HAOUSSA IDJILAD KEL ERKIL ARHAM KOROMIA HARAM DIENO KEL ADRAR ARHAM KIRCHAMBA DOUKOURIA BAGADADJI GOUREIGA MORIKOIRA TANGASSANE DEBE DIAWATOU FOUTARD FADJIBAYENDE KIRCHAMBA DIAWATOU DOUTA KOUNDAR INATABANE CHÉRIF YONE KEL DJILBAROU -

608 Journal Officiel De La Republique Du Mali

608 JOURNAL OFFICIEL DE LA REPUBLIQUE DU MALI DECRET N°06-164/P-RM DU 7 AVRIL 2006 FIXANT ARTICLE 2 : Le Programme d'Investissement et de L'ORGANISATION ET LES MODALITES DE Développement Rural des Régions du Nord Mali est FONCTIONNEMENT DU PROGRAMME rattaché au Commissariat à la Sécurité Alimentaire . D'INVESTISSEMENT ET DE DEVELOPPEMENT RURAL DES REGIONS DU NORD MALI ARTICLE 3 : La zone d'intervention du Programme d'Investissement et de Développement Rural des Régions LE PRESIDENT DE LA REPUBLIQUE, du Nord Mali couvre quatorze (14) communes des Régions de Tombouctou et Gao : Vu la Constitution ; - Haribomo, Hamzakona, Séréré et Rharouss dans le cercle Vu la Loi N° 94-009 du 22 mars 1994 portant principes de Gourma Rharouss ; fondamentaux de la création, de l'organisation, de la gestion et du contrôle des services publics modifiée par la Loi N° - Bamba, Téméra, Bourem, Taboye dans le cercle de 02-048 du 22 juillet 2002 ; Bourem ; Vu l'Ordonnance N°05-027/P-RM du 27 septembre 2005 - Ber dans le cercle de Tombouctou. autorisant la ratification de l'accord de financement du Programme d'Investissement et de Développement Rural - Soumpi, Souboundou et Banikane Narhawa dans le cercle des Régions du Nord Mali, signé le 24 mai 2005 entre le de Niafunké ; Gouvernement du Mali et le Fonds International de Développement Agricole ; - Tonka dans le cercle de Goundam ; - Tindirma dans le cercle de Diré. Vu l'Ordonnance N°06-012/P-RM du 28 mars 2006 portant création du Programme d'Investissement et de En outre, le Programme d'Investissement et de Développement Rural des Régions du Nord Mali ; Développement Rural des Régions du Nord Mali apporte des appuis spécifiques à des communes pastorales Vu le Décret N° 204/PG-RM du 21 août 1985 déterminant périphériques de la zone d'intervention. -

Andrew Dillon (2007): Mesurer L'impact Du Programme Mali-Nord Étude Sur La Pauvreté Et La Sécurité Alimentaire Au Nord M

Andrew Dillon (2007): Mesurer l’impact du Programme Mali-Nord Étude sur la Pauvreté et la Sécurité Alimentaire au Nord Mali Résumé de l’étude 1. Le présent rapport propose une évaluation de l’impact des interventions du Programme Mali-Nord sur la réduction de la pauvreté et sur la production agricole. Il s’appuie sur les résultats d’une enquête sur les revenus des ménages, l’Étude sur la Pauvreté et la Sécurité Alimentaire au Nord Mali 2006. Entre février et octobre 2006, cette enquête a concerné des hommes et femmes de ménages établis dans 151 villages du Nord du Mali, situés dans sept cercles (Niafunké, Goundam, Diré, Tombouctou, Rharous, Bourem et Kidal). L’échantillon complet compte également les communes suivantes : la ville de Kidal dans le cercle de Kidal ; Bourem, Bamba et Temera dans le cercle de Bourem ; Séréré, Rharous, Hamzakona et Banikane dans le cercle de Gourma Rharous ; Lafia, Bourem-Inaly, Ber, la ville de Tombouctou et Alafia dans le cercle de Tombouctou ; Tonka, Hangabera, M’Bouna, Essakane, Douékiré, Bintagoungou et la ville de Goundam dans le cercle de Goundam ; Arham, Binga, Bourem Sidi Amar, Dangha, la ville de Diré, Garbakoïra, Haïbongo, Kondi, Sareyamou et Tienkour dans le cercle de Diré ; enfin Soboundou, Léré, Banikane Narhawa, Dianké, Fittouga, Koumaïra, N’Gorkou et Soumpi dans le cercle de Niafunké. Parmi les 2.658 ménages de l’échantillon, les 245 foyers de la commune de Soboundou dans le cercle de Niafunké, déjà sondés lors d’une enquête menée en 1997-98, ont été à nouveau sondés deux fois en février/mars puis en août/septembre 2006. -

Régions De SEGOU Et MOPTI République Du Mali P! !

Régions de SEGOU et MOPTI République du Mali P! ! Tin Aicha Minkiri Essakane TOMBOUCTOUC! Madiakoye o Carte de la ville de Ségou M'Bouna Bintagoungou Bourem-Inaly Adarmalane Toya ! Aglal Razelma Kel Tachaharte Hangabera Douekiré ! Hel Check Hamed Garbakoira Gargando Dangha Kanèye Kel Mahla P! Doukouria Tinguéréguif Gari Goundam Arham Kondi Kirchamba o Bourem Sidi Amar ! Lerneb ! Tienkour Chichane Ouest ! ! DiréP Berabiché Haib ! ! Peulguelgobe Daka Ali Tonka Tindirma Saréyamou Adiora Daka Salakoira Sonima Banikane ! ! Daka Fifo Tondidarou Ouro ! ! Foulanes NiafounkoéP! Tingoura ! Soumpi Bambara-Maoude Kel Hassia Saraferé Gossi ! Koumaïra ! Kanioumé Dianké ! Leré Ikawalatenes Kormou © OpenStreetMap (and) contributors, CC-BY-SA N'Gorkou N'Gouma Inadiatafane Sah ! ! Iforgas Mohamed MAURITANIE Diabata Ambiri-Habe ! Akotaf Oska Gathi-Loumo ! ! Agawelene ! ! ! ! Nourani Oullad Mellouk Guirel Boua Moussoulé ! Mame-Yadass ! Korientzé Samanko ! Fraction Lalladji P! Guidio-Saré Youwarou ! Diona ! N'Daki Tanal Gueneibé Nampala Hombori ! ! Sendegué Zoumané Banguita Kikara o ! ! Diaweli Dogo Kérengo ! P! ! Sabary Boré Nokara ! Deberé Dallah Boulel Boni Kérena Dialloubé Pétaka ! ! Rekerkaye DouentzaP! o Boumboum ! Borko Semmi Konna Togueré-Coumbé ! Dogani-Beré Dagabory ! Dianwely-Maoundé ! ! Boudjiguiré Tongo-Tongo ! Djoundjileré ! Akor ! Dioura Diamabacourou Dionki Boundou-Herou Mabrouck Kebé ! Kargue Dogofryba K12 Sokora Deh Sokolo Damada Berdosso Sampara Kendé ! Diabaly Kendié Mondoro-Habe Kobou Sougui Manaco Deguéré Guiré ! ! Kadial ! Diondori -

9781464804335.Pdf

Land Delivery Systems in West African Cities Land Delivery Systems in West African Cities The Example of Bamako, Mali Alain Durand-Lasserve, Maÿlis Durand-Lasserve, and Harris Selod A copublication of the Agence Française de Développement and the World Bank © 2015 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / Th e World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved 1 2 3 4 18 17 16 15 Th is work is a product of the staff of Th e World Bank with external contributions. Th e fi ndings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily refl ect the views of Th e World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent, or the Agence Française de Développement. Th e World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. Th e boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of Th e World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of Th e World Bank, all of which are specifi cally reserved. Rights and Permissions Th is work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo. Under the Creative Commons Attribution license, you are free to copy, distribute, transmit, and adapt this work, including for commercial purposes, under the following conditions: Attribution—Please cite the work as follows: Durand-Lasserve, Alain, Maÿlis Durand-Lasserve, and Harris Selod. -

Geo-Epidemiology of Malaria at the Health Area Level, Dire Health District, Mali, 2013–2017

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Geo-Epidemiology of Malaria at the Health Area Level, Dire Health District, Mali, 2013–2017 Mady Cissoko 1,2,3,* , Issaka Sagara 1,2, Moussa H. Sankaré 3, Sokhna Dieng 2, Abdoulaye Guindo 1,4, Zoumana Doumbia 3, Balam Allasseini 3, Diahara Traore 5, Seydou Fomba 5, Marc Karim Bendiane 2, Jordi Landier 2, Nadine Dessay 6 and Jean Gaudart 1,7 1 Malaria Research and Training Center—Ogobara K. Doumbo (MRTC-OKD), FMOS-FAPH, Mali-NIAID-ICER, Université des Sciences, des Techniques et des Technologies de Bamako, Bamako 1805, Mali; [email protected] (I.S.); [email protected] (A.G.); [email protected] (J.G.) 2 Aix Marseille Université (AMU), Institut national de la santé et de la recherche médicale (INSERM), Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD), 13005 Marseille, France; [email protected] (S.D.); [email protected] (M.K.B.); [email protected] (J.L.) 3 Direction Régionale de la Santé de Tombouctou, Tombouctou 59, Mali; [email protected] (M.H.S.); [email protected] (Z.D.); [email protected] (B.A.) 4 Mère et Enfant face aux Infections Tropicales (MERIT), IRD, Université Paris 5, 75006 Paris, France 5 Programme National de la Lutte contre le Paludisme (PNLP Mali), Bamako 233, Mali; [email protected] (D.T.); [email protected] (S.F.) 6 ESPACE-DEV, UMR228 IRD/UM/UR/UG/UA, Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD), 34093 Montpellier, France; [email protected] 7 Aix Marseille Université, APHM, INSERM, IRD, SESSTIM, Hop