Chapter 1 the United States Legal System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legal Research 1 Ll.M

LEGAL RESEARCH 1 LL.M. Legal Research PRELIMINARIES Legal Authority • Legal Authority can be… • Primary—The Law Itself • Secondary—Commentary about the law Four Main Sources of Primary Authority . Constitutions Establishes structure of the government and fundamental rights of citizens . Statutes Establishes broad legislative mandates . Court Opinions (also called Cases) Interprets and/or applies constitution, statutes, and regulations Establishes legal precedent . Administrative Regulations Fulfills the legislative mandate with specific rules and enforcement procedures Primary Sources of American Law United States Constitution State Constitutions Executive Legislative Judicial Executive Legislative Judicial Regulations Statutes Court Opinions Regulations Statutes Court Opinions (Cases) (Cases) Federal Government State Government Civil Law Common Law Cases • Illustrate or • Interpret exemplify code. statutes • Not binding on • Create binding third parties precedent Statutes (codes) • Very specific • Broader and and detailed more vague French Intellectual Property Code Cases interpret statutes: Parody, like other comment and criticism, may claim fair use. Under the first of the four § 107 factors, “the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature ...,” the enquiry focuses on whether the new work merely supersedes the objects of the original creation, or whether and to what extent it is “transformative,” altering the original with new expression, meaning, or message. The more transformative the new work, the less will be the significance of other factors, like commercialism, that may weigh against a finding of fair use. The heart of any parodist's claim to quote from existing material is the use of some elements of a prior author's composition to create a new one that, at least in part, comments on that author's work. -

Mandatory V. Persuasive Cases

TEACHABLE MOMENTS FOR STUDENTS… 8383 PERSPECTIVES regulations, administrative agency decisions, MANDATORY V. executive orders, and treaties. Secondary authority, PERSUASIVE CASES basically, is everything else: articles, Restatements, treatises, commentary, etc. The most useful While decision BY BARBARA BINTLIFF authority addresses your legal issue and is close to “ your factual situation. While decision makers are makers are Barbara Bintliff is Director of the Law Library and usually willing to accept guidance from a wide Associate Professor of Law at the University of Colorado range of sources, only a primary authority can be usually willing in Boulder. She is also a member of the Perspectives mandatory in application. Editorial Board. Just because an authority is primary, however, to accept Teachable Moments for Students ... is does not automatically make its application in a designed to provide information that can be used for given situation mandatory. Some primary author- guidance from quick and accessible answers to the basic questions ity is only persuasive. The proper characterization that are frequently asked of librarians and those of a primary authority as mandatory or persuasive a wide range involved in teaching legal research and writing. is crucial to any proceeding; it can make the differ- These questions present a “teachable moment,” a ence between success and failure for a client’s of sources, brief window of opportunity when-—because he or cause. This is true of all primary authority, but this she has a specific need to know right now—the column will address case authority only. only a primary student or lawyer asking the question may actually Determining when a court’s decision is manda- remember the answer you provide. -

Corpus Juris Secundum Secondary Authority

Corpus Juris Secundum see Secondary Authority below Beware Corpus Juris Secundum is Roman Civil Law and it is a Secondary Authority. Maxims are the Primary Authority, the Chiefest Authority. (It would be nice to find a copy of Corpus Juris by the American Law Book Company; the first edition.) From Wikipedia: Corpus Juris Secundum (C.J.S.) is an encyclopedia of U.S. law (see Secondary Authority below). Its full title is Corpus Juris Secundum: Complete Restatement Of The Entire American Law As Developed By All Reported Cases (1936- ) It contains an alphabetical arrangement of legal topics as developed by U.S. defacto federal and defacto state cases. (Corporation Law) CJS is an authoritative American legal encyclopedia that provides a clear statement of each area of law including areas of the law that are evolving and provides footnoted citations to case law and other primary sources of law. Named after the 6th century Corpus Juris Civilis of Emperor Justinian I of the Byzantine Empire, the first codification of Roman law and civil law. (The name Corpus Juris literally means "body of the law"; Secundum denotes the second edition of the encyclopedia, which was originally issued as Corpus Juris by the American Law Book Company.) (Now published by the British Company, West) CJS is published by West, a Thomson Reuters business. It is updated with annual supplements to reflect modern developments in the law. Entire volumes are revised and reissued periodically as the supplements become large enough. It is also on Westlaw.[1] Before Thomson's acquisition of West, the CJS competed against the American Jurisprudence legal encyclopedia Secondary Authority Afforded less weight than the actual texts of primary authority. -

![[Appendix E – 1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3935/appendix-e-1-3233935.webp)

[Appendix E – 1]

[APPENDIX E – 1] UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON SCHOOL OF LAW LAW LIBRARY COLLECTION DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY A. IN GENERAL A usable academic law collection should be broad enough to cover most legal subjects, but does not need to cover each subject in equal depth. Also, it is undesirable to have one or two subjects covered exhaustively while having little or nothing on numerous other important subjects. To avoid these imbalances, collection levels have been established to set subject priorities based on the needs of the law libraries users. B. DEFINITIONS (1) AUTHORITY Legal materials are divided into two categories: (a) PRIMARY LEGAL AUTHORITY Primary legal authority is defined as a publication containing statements of rules and law made by persons or institutions who have been legally empowered to declare what the law is. Examples of primary legal authority include constitutions, statutes, judicial decisions, administrative regulations and decisions, and executive proclamations. (b) SECONDARY LEGAL AUTHORITY Secondary legal authority is defined as publications containing statements of opinion as to what the law may be made by persons or groups not legally empowered to declare what the law is. Examples of secondary authority include Restatements, Model codes, treatises, periodicals, casebooks, legislative history materials, and loose-leaf services. (2) COLLECTION LEVELS Collection levels for the purposes of completeness of acquisitions are as follows: (a) INTENSIVE LEVEL A collecting level that will support advanced research with the highest degree of effectiveness and a minimum reliance on inter-library loan or photocopying from other libraries. This level allows for the indefinite expansion of designated portions of the library's general collection and resource materials to the point that the collection may approach or achieve exhaustiveness in the sense that every available title in the designated categories is added to the collection. -

Sources of American Law an Introduction to Legal Research

Sources of American Law An Introduction to Legal Research Third Edition Beau Steenken Instructional Services Librarian University of Kentucky College of Law Tina M. Brooks Electronic Services Librarian University of Kentucky College of Law CALI eLangdell Press 2017 Chapter 1 The United States Legal System The simplest form of remedy for the uncertainty of the regime of primary rules is the introduction of what we shall call a ‘rule of recognition’… Wherever such a rule of recognition is accepted, both private persons and officials are provided with authoritative criteria for identifying primary rules of obligation. – H.L.A. Hart, The Concept of Law We the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America. – Preamble to the United States Constitution 1.1 Learning Objectives for Chapter 1 In working through this chapter, students should strive to be able to: • Describe key features of the U.S. legal system including: o Federalism, o Separation of Powers, o Sources of Law, and o Weight & Hierarchy of Authority. • Assess how the structure of the legal system frames research. 1.2 Introduction to Researching the Law The practice of law necessarily involves a significant amount of research. In fact, the average lawyer spends much of her work time researching. This makes sense when one considers that American law as a field is too vast, too varied, and too detailed for any one lawyer to keep all of it solely by memory. -

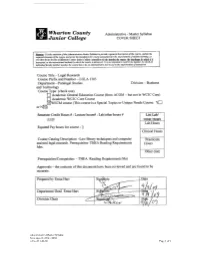

LGLA 1303 Legal Research

Administrative - Master Syllabus COVER SHEET Purpose : It is the intention of this Administrative-Master Syllabus to provide a general description of the course, outline the required elements of the course and to lay the foundation for course assessment for the improvement of student learning, as specified by the faculty of Wharton County Junior College, regardless of who teaches the course, the timeframe by which it is instructed, or the instructional method by which the course is delivered. It is not intended to restrict the manner by which an individual faculty member teaches the course but to be an administrative tool to aid in the improvement of instruction. Course Title – Legal Research Course Prefix and Number – LGLA 1303 Department – Paralegal Studies Division –Technology & Business Course Type: (check one) Academic General Education Course (from ACGM – but not in WCJC Core) Academic WCJC Core Course WECM course (This course is a Special Topics or Unique Needs Course: Y or N ) Semester Credit Hours # : Lecture hours# : Lab/other hours # 3:3:0 List Lab/ Other Hours Equated Pay hours for course - 3 Lab Hours Clinical Hours Course Catalog Description –Presents standard and/or computer assisted legal research techniques in a law library emphasizing the paralegal's role. Practicum Hours Other (list) Prerequisites/Corequisites-THEA Reading Requirements Met Prepared by Erma Hart Date 10/6/11 Reviewed by department head Erma Hart Date 10/6/11 Accuracy verified by Division Chair David Kucera Date10/15/11 Approved by Dean of Vocational Instruction or Vice President of Instruction Lac Date 11-9-12 Administrative-Master Syllabus form approved June/2006 revised 11-02-06 Page 1 of 3 Administrative - Master Syllabus I. -

Primary Authority Or Secondary Authority?

88 BRUTAL CHOICES IN CURRICULAR DESIGN… PERSPECTIVES WHAT SHOULD BE TAUGHT FIRST: PRIMARY AUTHORITY OR SECONDARY AUTHORITY? Brutal Choices in Curricular Design ... is a regular feature of Perspectives, designed to explore the difficult curricular decisions that teachers of legal research and writing courses are often forced to make in light of the realities of limited budgets, time, personnel, and other resources. Readers are invited to comment on the opinions expressed in this column and to suggest other “brutal choices” that should be considered in future issues. Please submit material to Helene Shapo, Northwestern University School of Law, 357 East Chicago Avenue, Chicago, IL 60611, phone: (312) 503-8454, fax: (312) 503-2035. Editor’s Note: In this installment of Brutal Choices, Penny A. Hazelton and Donald J. Dunn, two experienced legal research teachers who are also well known for their writings on the subject, take up the difficult curricular decision of what to introduce first to 1L students: primary or secondary authority. students first about court reports misleads them WHY DON’T WE TEACH about the role of judicial decisions in the rule of SECONDARY MATERIALS law and confuses them as they later learn how to solve a legal research problem. FIRST? For many years I have been using a modified version of Professor Marjorie Rombauer’s BY PENNY A. HAZELTON1 research strategy from her book, Legal Problem 6 Penny A. Hazelton is Professor of Law and Law Solving. She suggests five steps in the research Librarian of the Marian Gould Gallagher Law Library process—preliminary analysis; search for statutes; at the University of Washington School of Law, Seattle, search for mandatory case authority; search for Washington. -

State and Federal Tax Clinics

USD Tax Clinics Dan Kimmons Reference Librarian USD Legal Research Center 619.260.6846 [email protected] Overview • Learn about the sources of tax law; • Learn and apply research methodology when approaching tax problems; • Critically analyze tax law sources; • Tax research databases Primary & Secondary Authority Primary Authority Secondary Authority • Resources from a primary • Provide an explanation of branch of government primary authorities (legislative, executive • Law reviews / journal judicial) articles • Constitutions • Treatises • Statutes • Textbooks • Regulations • Looseleaf services • Judicial Decisions • Legislative history (even • IRS Documents if published by the gov’t) Hierarchy of Authority • Primary authority (usually) carries more weight than secondary authority • Sometimes a primary authority carries more weight than other types of primary authority • How do you define authority? • Precedential/Mandatory • Persuasive • Substantial Precedential & Persuasive Authority • Precedential Authority • Authority that must be followed by a court or agency • Persuasive Authority • Authority that is given little, if any, deference by a court or agency • Substantial Authority • Unique to tax situations – taxpayer penalties can be waived if substantial authority exists to support a position • Treasury regulations lists items considered “substantial authority” IRC §6662: “substantial authority” for the taxpayer means = IRC, temporary and final Regulations, court cases, administrative pronouncements, tax treaties, and congressional -

Research Guide

Sources of Law University of Idaho College of Law SOURCES OF LAW There are four sources of law at the state and federal levels: Constitutions Statutes Court Opinions Administrative Regulations Constitutions A constitution establishes a system of government and defines the boundaries of authority granted to the government. The United States Constitution is the preeminent source of law in the American legal system. All other statutes, court opinions and regulations must comply with its requirements. Each state also has its own constitution. A state constitution may grant greater rights than those secured by the federal constitution but cannot provide lesser rights than the federal constitution. Copies of the U.S. Constitution and the Idaho Constitution are found at the beginning of the Idaho Code. Statutes Statutes are statements of law enacted by federal and state legislatures. Statutes passed during a legislative session are organized by subject and published in a code. Federal statutes are published in the United States Code. Idaho statutes are published in the Idaho Code. Court Opinions Courts interpret statutes promulgated by the legislative and rules created by the executive branch of government. Statute and rules deemed unconstitutional by the court are invalidated. As a source of law, court opinions are known as the common law. Although the courts can create common law, legislatures have the power to change or abolish them, if the legislation is constitutional. There are many publications, called reports or reporters, that publish cases. See attached charts for reports and reporters that publish federal and Idaho cases. Administrative Regulations Administrative agencies are created by legislative action and operate under the control of the executive branch. -

Core Legal Research Competencies: a Compendium of Skills and Values As Defined in the Aba's Maccrate Report

CORE LEGAL RESEARCH COMPETENCIES: A COMPENDIUM OF SKILLS AND VALUES AS DEFINED IN THE ABA'S MACCRATE REPORT A REPORT BY THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF LAW LIBRARIES' RESEARCH INSTRUCTION CAUCUS PREPARED BY THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON RESEARCH CERTIFICATION EDITED BY ELLEN M. CALLINAN July 1997 INTRODUCTION This report is the work product of a dedicated group of law librarians from all over the United States, who devoted many hours of research and writing to this mission. The librarians were led by four regional coordinators who deserve special recognition for their efforts to persuade, encourage and even cajole so many very busy people into contributing sections to this document. Those four outstanding individuals are: James Hambleton James W. Hart Patricia Pelz Hart Patricia G. Strougal The Research Instruction Caucus was disbanded in 1995, but its spirit lives on the Research Instruction and Patron Services Special Interest Section of the AALL. To all those who contributed their thoughts, words and deeds to this project, take pride in the completion of this major undertaking. To all those who find some use for this document, your implementation of these ideas will give life to our work. Ellen M. Callinan Washington, DC July 1997 PART A - CASELAW.......................................................................................................1W 1. Characteristics......................................................................................................1 (A) Organization of the Federal and State Courts ...................................................1 -

Know Your Terms by Downloading Our Glossary

ThomsonSection Title: Reuters Subsection LawEikon / AccessSchool visual Survival identity Occabor Guide sent eum quidici similibus, ex estiae. Optatiatur aut lam, Glossarysit, natur? Quis of cuptium terms nam fugiam iur sitiis et occusamus mi, sumque perum quis excerumque doluptam, sam nosam atiur reprat. Acitatis ad quatest, officae cessequi toruntis ipsa dolum id magnia cus eaque comnimollora quisti sitaspe rchicia vellab imusdamus acepratis con re vel int doluptate non eos nimus. Gent pel elese resseditis niatis cusdae volorro volupid molores voluptat qui desequunt. Do you speak lawyer? Get the 411 on terms you’ll need to know throughout law school 1 Thomson Reuters Law School Survival Guide Glossary of terms Are you fluent in ‘lawyer’ language? You will be by the end of your third year of law school. As you’re exposed to new tasks throughout your education, understanding the right terms will save time and can help you interpret the law. Get the 411. Lawyer Lingo. 2 Thomson Reuters Law School Survival Guide Glossary of terms Term Definition A Act An alternative name for statutory law. When introduced into the first house of the legislature, a piece of proposed legislation is known as a bill. When passed to the next house, it may then be referred to as an act. After enactment, the terms law and act may be used interchangeably. Adjudication The formal pronouncing or recording of a judgment or decree by a court. Administrative A governmental authority, other than a legislature or court, Agency which issues rules and regulations or adjudicates disputes arising under its statutes and regulations. -

LGLA 1303 Legal Research

Administrative-Master Syllabus form approved June/2006 revised 11-02-06 Page 1 of 1 Administrative-Master Syllabus form approved June/2006 revised 11-02-06 Page 2 of 2 I. Topical Outline – Each offering of this course must include the following topics (be sure to include information regarding lab, practicum, clinical or other non lecture instruction): Week 1 Topics: The legal system and sources of law. State and federal law. Role of paralegals in legal research. Overview of legal resources-primary and secondary authorities. The court system. The legal process. Finding tools. Week 2 Topics: Primary Authority and where to find it. Cases-state and federal. Hierarchy of the court system. Reporters, advance sheets and slip opinions. Citations and how to read a cite. Intro to finding tools for case law-digests, the West key number system and citators. Weeks 3-4 Topics: Continued discussion of digests. Cite checking in hardcopy and on-line materials. Cases, reported and slip opinions, and how to cite them. Discussion of uniform citation form, parallel cites and subsequent history. Research strategy and analysis. Week 5 Topics: Intro to case briefing. Intro to secondary authority. How to find case law by using finding tools and secondary authority. Discuss secondary authorities: dictionaries, thesauri, and encyclopedias, A.L.R.s, treatises, and hornbooks. Week 6 Topics: Continued discussion of secondary sources. Secondary authority that is used to find case law and secondary authority that is used to explain the law. Legal periodicals and the appropriate indices. Restatements. Week 7 Topics: Validating and Cite Checking. Week 8 Topics: Constitutions, statutes, and legislative material.