Plague in the Graeco-Roman World 430 BC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1614154442698 05 Preparedn

Brief Communication Preparedness of Siddha system of medicine in practitioner perspective during a pandemic outbreak with special reference to COVID-19 S. Rajalakshmi1*, K. Samraj2, P. Sathiyarajeswaran3, K. Kanagavalli4 1*, 2Research Associate, Siddha Clinical Research Unit (SCRU), Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh, India, 3Director, Siddha Central Research Institute (SCRI), Chennai, Tamilnadu, India, 4Director General, Central Council for Research in Siddha (CCRS), Chennai, Tamilnadu, India ABSTRACT COVID-19 (Corona Virus Disease-2019) is an infectious respiratory disease caused by the most recently discovered coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2 (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Corona virus-2). This new viral disease was unknown before the outbreak began in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. As of November 16th 2020, it affects about 54.3 million populations, death troll increased to 1.32 million cases in worldwide. Whereas in India 8.85 cases are infected with COVID-19, of which 1, 30, 112 cases were died. Till now there has been no specific anti-virus drug or vaccines are available for the treatment of this disease, the supportive care and non-specific treatment to the symptoms of the patient are the only options in Biomedicine, the entire world turns its attention towards alternative medicine or Traditional medicine. Siddha medicine is one of the primordial systems of medicine practiced in the southern part of India, it dealt a lot about pandemic, and its management. This review provides an insight into Pandemic in Siddha system and its management in both ancient history and modern history, National and state level Government policies related to current pandemic, World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines on usage of unproven drug during infectious disease outbreak, Preparedness of Siddha system during a pandemic outbreak Challenges and Recommendations. -

People, Plagues, and Prices in the Roman World: the Evidence from Egypt

People, Plagues, and Prices in the Roman World: The Evidence from Egypt KYLE HARPER The papyri of Roman Egypt provide some of the most important quantifiable data from a first-millennium economy. This paper builds a new dataset of wheat prices, land prices, rents, and wages over the entire period of Roman control in Egypt. Movements in both nominal and real prices over these centuries suggest periods of intensive and extensive economic growth as well as contraction. Across a timeframe that covers several severe mortality shocks, demographic changes appear to be an important, but by no means the only, force behind changes in factor prices. his article creates and analyzes a time series of wheat and factor Tprices for Egypt from AD 1 to the Muslim conquest, ~AD 641. From the time the territory was annexed by Octavian in 30 BCE until it was permanently taken around AD 641, Egypt was an important part of the Roman Empire. Famously, it supplied grain for the populations of Rome and later Constantinople, but more broadly it was integrated into the culture, society, and economy of the Roman Mediterranean. While every province of the sprawling Roman Empire was distinctive, recent work stresses that Egypt was not peculiar (Bagnall 1993; Rathbone 2007). Neither its Pharaonic legacy, nor the geography of the Nile valley, make it unrepresentative of the Roman world. In one crucial sense, however, Roman Egypt is truly unique: the rich- ness of its surviving documentation. Because of the valley’s arid climate, tens of thousands of papyri, covering the entire spectrum of public and private documents, survive from the Roman period (Bagnall 2009). -

Bibliographic Review on the Historical Memory of Previous

REVISIONES Bibliographic review on the historical memory of previous pandemics in nursing reviews on COVID-19: a secularly documented reality Revisión bibliográfica sobre la memoria histórica de pandemias anteriores en revisiones de enfermería sobre COVID-19: una realidad secularmente documentada Joaquín León Molina1 M. Fuensanta Hellín Gil1 Eva Abad Corpa2 1 Nurse Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca de Murcia; Advanced Nursing Care Group of the Murcian Institute of Biosanitary Research Arrixaca. Murcia. Spain. 2 Associate nurse, Hospital General Universitario Reina Sofía de Murcia; Contracted Professor PhD linked University of Murcia. Advanced Nursing Care Group of the Murcian Institute of Biosanitary Research Arrixaca. Murcia. Spain. https://doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.456511 Received: 17/11/2020 Accepted: 10/01/2021 ABSTRACT: Introduction: Reviews for COVID-19 should reflect historical antecedents from previous pandemics. Objective: We plan to map the content of recent reviews in the nursing area on COVID-19 to see if it refers to health crises due to epidemics and infectious diseases. Methodology: Descriptive narrative review. The Science Web, PubMed and Lilacs were consulted to identify the reviews; The content of the documents was consulted to detect the presence of descriptors and terms related to pandemics prior to the 21st century of humanity, taking into account the inclusion criteria and objectives of the study. Results: Relevant reviews were found only in 11 documents of the 192 identified. Conclusions: There may be reluctance to use documentation published more than a century ago; However, it would be advisable not to lose the historical memory of pandemic crises that humanity has suffered for millennia Key words: Pandemics; Epidemics; History; Ancient History. -

Microbiology E-Journal

From the Principal’s Desk I would like to congratulate the entire team of Department of Microbiology for their wonderful though very strenuous attempt to publish a journal exclusively for the students. Presently the e-version of the journal is going to be released on auspicious day of 5th September, i.e. the Teacher's Day. I hope, later on the print version will be published. In my perception it is a tribute to the entire faculty members by the students because these write ups simply say that how much they assimilate from their teachers in this subject. We all know and still experiencing a very stressful as well as fearful daily life due to the pandemic. We came to know many information regarding this covid-19 virus from many microbiologists not only from India but also from other countries like Canada, USA and many more. The Department of Microbiology, Vijaygarh Jyotish Ray College produced many students who are pursuing their research in India as well as abroad. In response to the call from their teachers they shared their knowledge with us in many webinars organized by the department. In my perception all the students of this department are budding scientist of future. No one knows it may so happen that we come to know that one of our students succeed to be associated with the invention of any life-saving drug or vaccine. Once again, I want thank all students and faculties for initiating this attempt and hope that this will continue to publish. Dr. Rajyasri Neogy, Principal, Vijaygarh Jyotish Ray College Contents Paper Title Page No. -

A Treatise Offered in a Time of Pestilence by St. Cyprian of Carthage

A Treatise Offered in a Time of Pestilence by St. Cyprian of Carthage The Plague of Cyprian was a pandemic that afflicted the Roman Empire from about AD 249 to 262. The plague is thought to have caused widespread manpower shortages for food production and the Roman army, severely weakening the empire during the Crisis of the Third Century. Its modern name commemorates St. Cyprian, Bishop of Carthage, an early Christian writer who witnessed and described the plague. The agent of the plague is highly speculative due to sparse sourcing, but suspects include smallpox, pandemic influenza and viral hemorrhagic fever (filoviruses) like the Ebola virus. In 250 to 262, at the height of the outbreak, 5,000 people a day were said to be dying in Rome. Cyprian's biographer, Pontius of Carthage, wrote of the plague at Carthage: Afterwards there broke out a dreadful plague, and excessive destruction of a hateful disease invaded every house in succession of the trembling populace, carrying off day by day with abrupt attack numberless people, every one from his own house. All were shuddering, fleeing, shunning the contagion, impiously exposing their own friends, as if with the exclusion of the person who was sure to die of the plague, one could exclude death itself also. There lay about the meanwhile, over the whole city, no longer bodies, but the carcasses of many, and, by the contemplation of a lot which in their turn would be theirs, demanded the pity of the passers-by for themselves. No one regarded anything besides his cruel gains. -

Europe: 400 to 301 B.C. 9/13/11 3:16 PM

Europe: 400 to 301 B.C. 9/13/11 3:16 PM Connexions You are here: Home » Content » Europe: 400 to 301 B.C. Europe: 400 to 301 B.C. Module by: Jack E. Maxfield. Europe Back to Europe: 500 to 401 B.C. (http://cnx.org/content/m17852/latest/) SOUTHERN EUROPE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN ISLANDS In the last third of this century, all these islands were conquered by the men of Alexander the Great, but his control was short-lived. By 323 B.C. Rhodes was independent again and Cyprus belonged to Egypt until Demetrius Poliocertes, aspirant to the throne of Macedon, took Cyprus again. Then in 307 he besieged Rhodes, using 30,000 men to build siege towers and engines, but all of this failed. (Ref. 38 (http://cnx.org/content/m17805/latest/#threeeight) , 222 (http://cnx.org/content/m17805/latest/#twotwotwo) ) GREECE Throughout the peninsula there was endless conflict between the slaves and the ruined proletarian masses who demanded that the state support them. Up until about 378 B.C. the police force of Athens consisted of about 300 state-owned Scythian slaves. At the beginning of the century Sparta, having won the Peloponnesian War with the help of subsidies from Persia, dominated southern Greece; then, by forming an "Arcadian League", Thebes took over control from about 370 to 360 B.C.; then Athens, with growing special- ization of professional soldiers and generals, professional orators and financial experts be- came supreme for awhile. But in the last part of the century the unity which the Greeks could not find among themselves was forced on them by Philip of Macedon. -

Download This PDF File

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF BUSINESS & MANAGEMENT ISSN 2321–8916 www.theijbm.com THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF BUSINESS & MANAGEMENT Effect of Coronavirus Pandemic (Covid 19) on Nigerian Economy: A study of Tummy-Tummy Noodles Producing Firm in Kaduna, Nigeria Nduji Romanus Lecturer, Department of Business Administration, Veritas University, Abuja, Nigeria Oyenuga Michael Lecturer, Department of Marketing, Veritas University, Abuja, Nigeria Idewele Israel Lecturer, Department of Banking and Finance, Veritas University, Abuja, Nigeria Oriaku Christian Lecturer, Department of Business Administration, Veritas University, Abuja, Nigeria Abstract In Africa, the rate at which the incidence of co-vid 19 pandemic is escalating is alarming. Despite efforts made to reduce it through quarantines, lockdown, social/physical distancing and other measures by the Government, yet it is still on the rise especially in Nigeria. The research design adopted for this study is the descriptive design; while structured questionnaire was administered to raise data meant for empirical analysis. Findings from the study showed that Co-vid 19 has a positive and significant effect on Nigerian economy . In addition, Lockdown measure has a significant influence on economic activities of the firms in Nigeria. However, social / physical distancing was discovered to have an insignificant effect on the growth of the firms in Nigeria. Based on these findings, the study recommends that building situational awareness will require sustained investment in infectious disease surveillance, crisis management, and risk communications systems. Investments in these capacities are likely to surge after pandemic or epidemic events and then abate as other priorities emerge. If further recommends that Governments should avoid sweeping and overly broad restrictions on movement and personal liberty, and only move towards mandatory restrictions when scientifically warranted and necessary and when mechanisms for support of those affected can be ensured. -

Download This Issue

COVID ECONOMICS VETTED AND REAL-TIME PAPERS ECONOMIC EPIDEMIOLOGY: ISSUE 48 A REVIEW 10 SEPTEMBER 2020 David McAdams INDIVIDUALISM Bo Bian, Jingjing Li, Ting Xu FORECASTING THE SHOCK and Natasha Z. Foutz Felipe Meza ENTREPRENEUR DEBT AVERSION IS WHO TRUSTED? Mikael Paaso, Vesa Pursiainen Nirosha Elsem Varghese, Iryna and Sami Torstila Sabat, Sebastian Neuman‑Böhme, SUPPLY CHAIN DISRUPTION Jonas Schreyögg, Tom Stargardt, Matthias Meier and Eugenio Pinto Aleksandra Torbica, Job van Exel, PANDEMICS, POVERTY, AND Pedro Pita Barros and Werner Brouwer SOCIAL COHESION ECONOMISTS: FROM VILLAINS Remi Jedwab, Amjad M. Khan, Richard TO HEROES? Damania, Jason Russ and Esha D. Zaver Diane Coyle Covid Economics Vetted and Real-Time Papers Covid Economics, Vetted and Real-Time Papers, from CEPR, brings together formal investigations on the economic issues emanating from the Covid outbreak, based on explicit theory and/or empirical evidence, to improve the knowledge base. Founder: Beatrice Weder di Mauro, President of CEPR Editor: Charles Wyplosz, Graduate Institute Geneva and CEPR Contact: Submissions should be made at https://portal.cepr.org/call-papers- covid-economics. Other queries should be sent to [email protected]. Copyright for the papers appearing in this issue of Covid Economics: Vetted and Real-Time Papers is held by the individual authors. The Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) The Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) is a network of over 1,500 research economists based mostly in European universities. The Centre’s goal is twofold: to promote world-class research, and to get the policy-relevant results into the hands of key decision-makers. CEPR’s guiding principle is ‘Research excellence with policy relevance’. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

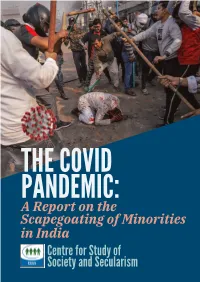

THE COVID PANDEMIC: a Report on the Scapegoating of Minorities in India Centre for Study of Society and Secularism I

THE COVID PANDEMIC: A Report on the Scapegoating of Minorities in India Centre for Study of Society and Secularism i The Covid Pandemic: A Report on the Scapegoating of Minorities in India Centre for Study of Society and Secularism Mumbai ii Published and circulated as a digital copy in April 2021 © Centre for Study of Society and Secularism All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including, printing, photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher and without prominently acknowledging the publisher. Centre for Study of Society and Secularism, 603, New Silver Star, Prabhat Colony Road, Santacruz (East), Mumbai, India Tel: +91 9987853173 Email: [email protected] Website: www.csss-isla.com Cover Photo Credits: Danish Siddiqui/Reuters iii Preface Covid -19 pandemic shook the entire world, particularly from the last week of March 2020. The pandemic nearly brought the world to a standstill. Those of us who lived during the pandemic witnessed unknown times. The fear of getting infected of a very contagious disease that could even cause death was writ large on people’s faces. People were confined to their homes. They stepped out only when absolutely necessary, e.g. to buy provisions or to access medical services; or if they were serving in essential services like hospitals, security and police, etc. Economic activities were down to minimum. Means of public transportation were halted, all educational institutions, industries and work establishments were closed. -

Fast-Tracking Vaccines for Epidemic Diseases: an Update from CEPI

Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations Fast-tracking vaccines for epidemic diseases: an update from CEPI Richard Hatchett, MD CEO, CEPI First traces of a mysterious disease Plague of Cyprian Started in Ethiopia before 250 CE and spread through Egypt, reaching Alexandria by 249 and Rome in 251, causing a pandemic lasting 20 years. At its peak, 5000 a day died in Rome. Its geographic scope was vast; it is attested everywhere we have sources. St. Cyprian, the Bishop of Carthage, left the most detailed account we have, saying he believed the kingdom of God to be at hand. Plague in the 21st Century cnn.com cnn.com • 2348 suspected cases (82 HCW), 202 deaths (November 22) • 55% of cases in Antananarivo and Toamasina • 16 of 22 regions reporting cases • Schools and universities closed, mass gatherings banned; travel advisories • South Africa, Mauritius, Seychelles, Tanzania, La Reunion, Mozambique, Kenya, Ethiopia and Comoros placed on high alert 44 Lassa outbreak in Nigeria • From 1st Jan to 4th March 2018 − Total reported suspected cases 1121 − 353 confirmed cases − 8 probable cases − 86 deaths (78 lab confirmed, 8 probable) − 16 Health care workers − CFR: 23.8% − Cases reported in 18 states LEGEND 0 1- 10 Cases − Ondo, Edo and Ebonyi most affected 11-40 Cases >60 1>suspected cases • Response being led by Nigeria CDC 1 dot = 1 Confirmed/Probable • WHO requested to coordinate proposition for research response • CEPI willing to support where it can, focussing on laying groundwork for future vaccine development including harmonisation -

ABSTRACT Constantinos Hasapis, Overcoming the Spartan

ABSTRACT Constantinos Hasapis, Overcoming the Spartan Phalanx: The Evolution of Greek Battlefield Tactics, 394 BC- 371 BC. (Dr. Anthony Papalas, Thesis Director), Spring 2012 The objective of this thesis is to examine the changes in Greek battlefield tactics in the early fourth century as a response to overthrowing what was widely considered by most of Greece tyranny on the part of Sparta. Sparta's hegemony was based on military might, namely her mastery of phalanx warfare. Therefore the key to dismantling Lacedaemonia's overlordship was to defeat her armies on the battlefield. This thesis will argue that new battle tactics were tried and although there were varying degrees of success, the final victory at Leuctra over the Spartans was due mainly to the use of another phalanx. However, the Theban phalanx was not a merely a copy of Sparta's. New formations, tactics, and battlefield concepts were applied and used successfully when wedded together. Sparta's prospects of maintaining her position of dominance were increasingly bleak. Sparta's phalanx had became more versatile and mobile after the end of the Peloponnesian War but her increasing economic and demographic problems, compounded by outside commitments resulting in imperial overstretch, strained her resources. The additional burden of internal security requirements caused by the need to hold down a massive helot population led to a static position in the face of a dynamic enemy with no such constraints Overcoming The Spartan Phalanx: The Evolution of Greek Battlefield Tactics, 394 BC-371 BC A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History East Carolina University In Partial Fulfillment for the Degree Master of Arts in History Constantinos Hasapis Spring 2012 Copyright 2012 Constantinos Hasapis Overcoming the Spartan Phalanx: The Evolution of Greek Battlefield Tactics, 394 BC-371 BC by Constantinos Hasapis APPROVED BY DIRECTOR OF THESIS ________________________________ Dr.