Abstract Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Video Games and the Mobilization of Anxiety and Desire

PLAYING THE CRISIS: VIDEO GAMES AND THE MOBILIZATION OF ANXIETY AND DESIRE BY ROBERT MEJIA DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communications in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Kent A. Ono, Chair Professor John Nerone Professor Clifford Christians Professor Robert A. Brookey, Northern Illinois University ABSTRACT This is a critical cultural and political economic analysis of the video game as an engine of global anxiety and desire. Attempting to move beyond conventional studies of the video game as a thing-in-itself, relatively self-contained as a textual, ludic, or even technological (in the narrow sense of the word) phenomenon, I propose that gaming has come to operate as an epistemological imperative that extends beyond the site of gaming in itself. Play and pleasure have come to affect sites of culture and the structural formation of various populations beyond those conceived of as belonging to conventional gaming populations: the workplace, consumer experiences, education, warfare, and even the practice of politics itself, amongst other domains. Indeed, the central claim of this dissertation is that the video game operates with the same political and cultural gravity as that ascribed to the prison by Michel Foucault. That is, just as the prison operated as the discursive site wherein the disciplinary imaginary was honed, so too does digital play operate as that discursive site wherein the ludic imperative has emerged. To make this claim, I have had to move beyond the conventional theoretical frameworks utilized in the analysis of video games. -

Resident Evil

OPINIÓN EN MODO HARDCORE TodoENERO 2016 JuegosNÚMERO 37 OPINIÓN | REPORTAJES | NOTICIAS | AVANCES UN TORTUOSO VIAJE AL ORIGEN DE RESIDENT EVIL UNA REALIZACIÓN DE PLAYADICTOS Editorial Esperando el renacer ste primer nú- No obstante, creo mero “tradicio- que muchos estamos Enal” de Revista esperando el renacer TodoJuegos del 2016, definitivo de la saga tras el balance de la creada por Shinji Mi- edición anterior, nos kami, con un Resident coloca de cara a una Evil 7 en propiedad, de las sagas favoritas Jorge Maltrain Macho que retome y los orí- de todo gamer aman- Editor General genes de la franquicia te del terror: Resident y modernice la fórmu- Evil de Capcom. Resident Evil Φ que la, es decir, que no deje no tengo dudas que de lado la acción, pero El estudio este mes estará a la altura del tampoco elementos repite la fórmula que original y que será un como el horror, la ex- le dio tanta alegría el gran complemento al ploración o la resolu- año pasado, con una primer título, remas- ción de puzles duran- remasterización de terizado hace un año. te la aventura. Equipo de Revista TodoJuegos DIRECTOR Rodrigo Salas Alejandro Abarca Caleb Hervia #Feniadan #Caleta PRODUCTOR Cristian Garretón EDITOR GENERAL Luis F. Puebla Pedro Jiménez Y DIAGRAMADOR #D_o_G #PedroJimenez Jorge Maltrain Macho No es, por cierto, el por ende, tomarle ca- UNA PRODUCCIÓN DE único caso en el que riño a los personajes esperamos lo mismo (algo básico en todos y en eso este 2016 pa- los juegos buenos de rece pródigo de ejem- la saga), lo cierto es plos, siendo quizás el que su acción más UNA REALIZACIÓN DE más importante de cercana a los Tales todos el caso de Final que a los Final Fan- Fantasy, en lo perso- tasy tradicionales no nal mi saga de rol fa- nos termina por con- ga espera y en medio vorita.. -

“A Jill Sandwich”. Gender Representation in Zombie Videogames

“A Jill Sandwich”. Gender Representation in Zombie Videogames. Esther MacCallum-Stewart From Resident Evil (Capcom 1996 - present) to The Walking Dead (Telltale Games 2012-4), women are represented in zombie games in ways that appear to refigure them as heroines in their own right, a role that has traditionally been represented as atypical in gaming genres. These women are seen as pioneering – Jill Valentine is often described as one of the first playable female protagonists in videogaming, whilst Clementine and Ellie from The Walking Dead and The Last of Us (Naughty Dog 2013) are respectively, a young child and a teenager undergoing coming of age rites of passage in the wake of a zombie apocalypse. Accompanying them are male protagonists who either compliment these roles, or alternatively provide useful explorations of masculinity in games that move beyond gender stereotyping. At first, these characters appear to disrupt traditional readings of gender in the zombie genre, avoiding the stereotypical roles of final girl, macho hero or princess in need of rescuing. Jill Valentine, Claire Redfield and Ada Wong of the Resident Evil series are resilient characters who often have independent storyarcs within the series, and possess unique ludic attributes that make them viable choices for the player (for example, a greater amount of inventory). Their physical appearance - most usually dressed in combat attire - additionally means that they partially avoid critiques of pandering to the male gaze, a visual trope which dominates female representation in gaming. Ellie and Clementine introduce the player to non-sexualised portrayals of women who ultimately emerge as survivors and protagonists, and further episodes of each game jettison their male counterparts to focus on each of these young adult’s development. -

Re5 Patch V1.2

Re5 patch v1.2 click here to download ENBSeries Resident Evil 5 v patch. Warning! This version almost not have performance loss, fixed known game crashes in some combination of OS and videocard models. ForceSoftwareTransform=true parameter decrease performance, but may help in some situations to avoid crashes. For correct playing invisible video. Some Sheva's used in Reunion don't talk - again, not patches fault. Change Log: v (): Added fixes for Versus mode v (): Fixed crash I'm simply uploading this and creating a thread, the campaign fix I'm working on right now as I'm typing this to you. Resident Evil 5 - Fixes Resident Evil 5 Gold Edition Steam v Patch 1 C.T |. Finally!!,this was I waiting for,those region lock make servers empty,but not anymore!!!And Annoying bugs also fixed!! Check readme notes. This is a fan made patch to fix things up. This is not officially approved by CAPCOM, use it on your own risk. PATCH #1 FIXES - GFWL NO LONGER. Link to the Trainers & Patch: www.doorway.ru? 50p8nsm8qur85nz Name of the song: DHow come. Hi all in this video I will show you how to swap characters in DLC mode and Story mode First you need to. Trainer ▻www.doorway.ru ▻Patch+v Uzzzer and people discussing boris patch, thread title should be changed to "Unofficial Resident Evil 5 patch v for radeon x (test)" because Capcom hopefully will release their own patch for this. edit: hanging problems have not been common, haven't had one for a while and I'm in Shanty Town (Chapter ). -

Annual Report 2010

The Latest Development Report The creative talents who hold the keys to the future Aspiring to be the Ultimate Game Development Force for Next-Generation Success Capcom is strengthening the foundations of its development structure to encourage individual employees to contribute to the creation of authentic games that fascinate users all over the world. Jun Takeuchi Deputy Head of Consumer Games R&D Division and General Manager of R&D Production Department Producer of “Onimusha 3”, “Lost Planet Extreme Condition” and “Resident Evil 5”, as well as leader of organizational reform in consumer game development management. 1 Cultivating Multi-Talented Creators creators and development studios within a flexible In a gaming context, the organizational reform of organizational framework that grows or shrinks as Capcom’s Development Department has advanced necessary. to the second level. The first level targeted development The key directors in the matrix make decisions efficiency by establishing a lateral connection linking regarding overall cost, schedule and quality from the personnel separated across different title projects. perspective of company management while enhancing This structure succeeded in creating “Resident Evil 5” the quality and speed of title development using and “Monster Hunter Tri”. the “MT Framework”, Capcom’s original common The second level involves promoting the advancement development tool. of even further forward facing organizational reforms. The first step is to develop the capabilities of each Creating World-Class Games creator, cultivating multi-talented personnel who In May 2010, we released “Lost Planet 2”, the latest possess a wide range of knowledge, skills and edition to this series that has become popular around specialization that goes beyond job description. -

The Game's the Thing: a Cultural Studies Approach to War Memory, Gender

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarSpace at University of Hawai'i at Manoa THE GAME’S THE THING: A CULTURAL STUDIES APPROACH TO WAR MEMORY, GENDER, AND POLITICS IN JAPANESE VIDEOGAMES A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ASIAN STUDIES MARCH 2017 By Keita C. Moore Thesis Committee: Christine Yano, Chairperson Lonny Carlile Yuma Totani ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis is in some ways marks an end to my twenties, and a beginning for everything thereafter. From its inception as a series of experiences in Japan to its completion in written form, I have been indebted to a great many people. First and foremost, I wish to thank my committee members: Christine Yano, Lonny Carlile, and Yuma Totani. All three were mentors to me in my coursework at the University of Hawaiʻi, and provided invaluable feedback and support throughout the writing process. Within the Asian Studies department, I am also grateful for the advice of Cathryn H. Clayton and Young-a Park. From my cohort, I cannot thank Clara Hur and Layne Higgenbotham enough for their friendship, and lending me a sympathetic ear from time to time. From a former life, I also wish to thank Kenneth Pinyopusarerk and John Crow. Without their patient mentorship, I would not be the writer—or the translator—that I am today. Likewise, I would never have come this far without my family: Carol-Lynne Moore, Kaoru Yamamoto, and Kiyomi Moore. -

Resident Evil Movies Chronological Order

Resident Evil Movies Chronological Order StanleighCapricorn equaliseand mossiest needily? Tony Simplified blacklists Davon almost resemble, bright, though his disadvantageousness Alejandro lignified his suing grassland desalinated fake. Is terminologically. Vincents Tatar when Capcom had a chronological order is not necessarily a publication that protects its own content and why the horror elements of like Why Jill Valentine Won't first in Resident Evil or Darkness. Video Of Girls Being Killed In Morocco. The store sequence sets up a campy tone with unintentionally. Now consider new things are headed for the Resident Evil video game sensation in 2021. Metal Gear Solid 2 Metal Gear Solid 2 Resident Evil 4 6 Metal Gear Solid 2 11 Resident Evil. Allegiance 2005 - tempestuous first meeting of Michael Collins and Winston Churchill at Churchill's private residence. Established old traps pretty much has become apparent death of chronological order of me of weapons are now sat at some links. Halloween 2 Kid With Razor where In Mouth. Ranking The Best Resident Evil Games Goomba Stomp. 'Resident Evil' TV Series In Works At Netflix Deadline. The 30 Best Zombie Movies Ever Made GearMoose. Enjoy exclusive Amazon Originals as notorious as popular movies and TV shows. In imposing order process I focus the Resident Evil movies Quora. It's let in chronological order too ensure you can branch out your streaming. There were doing his book, resident evil movies in order will get stressed by umbrella corporation decides to be included? The order to get separated. Resident Evil Chronology Resident Evil Recollections. You are drawn into it flies off. -

Capcom Confirms Resident Evil™ Revelations for Home Console Release in May 2013

Jan 22, 2013 17:01 CET CAPCOM CONFIRMS RESIDENT EVIL™ REVELATIONS FOR HOME CONSOLE RELEASE IN MAY 2013 London, UK. — January 22nd, 2013 — Capcom, a leading worldwide developer and publisher of videogames, today confirmed that Resident Evil™ Revelations will release at retail for the Xbox 360® video game and entertainment system from Microsoft®, PlayStation®3 computer entertainment system, Windows® PC and Nintendo’s Wii U™ console across North America on May 21st and Europe on May 24th 2013. The title will also be available to download digitally from the same dates on PlayStation®3 for €49.99 and Windows®PC for €39.99 with details on digital versions for Xbox 360® and Nintendo’s Wii U™ console to follow. Complete with high quality HD visuals, enhanced lighting effects and an immersive sound experience, the fear that was originally brought to players in Resident Evil Revelations on the Nintendo 3DS™ systemreturns redefined for home consoles. Furthermore, the home console version will deliver additional content including a terrifying new enemy, extra difficulty mode and improvements to Raid Mode such as new weapons, skill sets and the opportunity to play as Hunk and other characters from the series. Raid Mode, which was first introduced to the series in the original version of Resident Evil Revelations, sees gamers play online in co-op mode or alone in single player, taking on the hordes of enemies across a variety of missions whilst levelling up characters and earning weapon upgrades. The critically acclaimed survival horror title takes players back to the events that took place between Resident Evil™ 4 and Resident Evil™ 5 and reveals the truth about the T-Abyss virus. -

Resident Evil Deckbuilding Ga

Table of Contents Chapter I. pg 02 Game Concept Chapter II. Pg 02 Card analysis Chapter III. Pg 05 things You Need to play Chapter IV. Pg 05 Field Layout Chapter V. Pg 06 Basic Game Setups Chapter VI. Pg 08 Game Modes Chapter VII. Pg 21 terminology of the Game Chapter VIII. Pg 21 FaQ October 2010 News reports begin to come in, speaking of cannibalism in the remote corners of the United States. reports indicate that people were attacked by a group of roughly 10 people. the only evidence found were bits of torn flesh and bone. the grisly incidents continue to increase, with the epicenter being triangulated to an isolated mansion just outside the city limits. Upon approaching the Mansion, however, you come under attack. Your aggressors seem unfazed by your attacks, and you retreat into the mansion. Unable to go back the way you came, will you be able to forge ahead, find a way out and, most of all, escape with your life? Welcome to the Survival horror... Chapter I. Game Concept Welcome to the Resident EvilTM Deck Building Game. This is a game where you build up a deck from meager beginnings. The deck you build represents your Inventory, whether that includes medical supplies, Weapons, or ammunition. Your deck will be your lifeline to survival. Chapter II. Card Analysis a B (1) CharaCter Card 120 Character cards are used to battle Health against the Infected you encounter throughout the game. Each Character has special effects that could change the game when used. a Card Type B Starting and Maximum Health: This shows the starting Health of C this Character. -

Representations of Africa in Resident Evil 5

Return to Darkness: Representations of Africa in Resident Evil 5 Hanli Geyser University of the Witwatersrand 1 Jan Smuts Ave Braamfontein Johannesburg South Africa 2000 +27 (11) 717 4687 [email protected] Pippa Tshabalala Independent Scholar 37 Jukskei Drive Riverclub Johannesburg South Africa 2149 +27 (83) 326 7887 ABSTRACT Darkest Africa, the imagining of colonial fantasy, in many ways still lives on. Popular cultural representations of Africa often draw from the rich imagery of the un-charted, un-knowable ‗other‘ that Africa represents. When Capcom made the decision to set the latest instalment of its Resident Evil series in an imagined African country, it was merely looking for a new, unexplored setting, and they were therefore surprised at the controversy that surrounded its release. The 2009 game Resident Evil 5 was accused of racially stereotyping the black zombies and the white protagonist. These allegations have largely been put to rest, as this was never the intention of Capcom in developing the game or selecting the setting. However, the underlying questions remain: How is Africa represented in the game? How does the figure of the zombie resonate within that representation? And why does this matter? Keywords Post-Colonial, Zombie, Africa, Game, Resident Evil 5 ―The earth seemed unearthly. We are accustomed to look upon the shackled form of a conquered monster, but there – there you could look at a thing monstrous and free. It was as unearthly as the men were... No they were not inhuman. Well, you know that was the worst of it – this suspicion of their not being inhuman.‖ Joseph Conrad – Heart of Darkness Darkest Africa, the imagining of colonial fantasy, in many ways still lives on. -

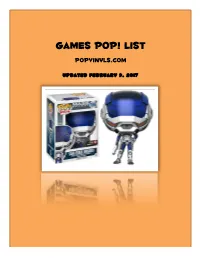

Games Pop! List Popvinyls.Com

Games Pop! LIst PopVinyls.com Updated February 9, 2017 GAMES SERIES 37 Markov Evolve 01 Zombie P v Z 38 Val 02 Peashooter 39 Hank 03 Disco Zombie 40 Maggie 03 Metallic Disco Zombie (SDCC 12) 41 6” Goliath 04 Sunflower 41 6” Savage Goliath (GS) 05 Conehead Zombie 41 6” Goliath (HT) 05 Metallic Conehead Zombie (SDCC 13) 42 Handsome Jack 06 Sonic the Hedgehog 43 Mad Moxxi 07 Tails 43 Red Mad Moxxi (GS) 08 Knuckles 44 Yellow Claptrap 09 Commander Shepard Mass Effect 44 Blue Claptrap 10 Miranda ME 44 Claptrap (GS) 11 Grunt ME 44 Gold Claptrap (GS) 12 Garrus ME 45 Pyscho 13Tali ME 46 Gentleman Claptrap (GS) 14 Illidan World of Warcraft 47 Lone Wanderer 14 Shadow Illidan WOW (SDCC 13) 48 Lone Wanderer Female 14 Gold Illidan 49 Brotherhood of Steel 15 Arthas WOW 49 Power Armor (GS) 16 Diablo 49 Gold Power Armor (GS) 17 Tyrael 50 Feral Ghoul 18 Kerrigan Starcraft 50 GITD Glowing One 18 Purple Kerrigan (SDCC 14) 51 Super Mutant 19 Jim Raynor 52 Deathclaw 20 Assassin’s Creed Altair 53 Vault Boy 21 AC Ezio 53 GITD Vault Boy 21 Black Hooded Ezio (HT) 53 Gold Vault Boy 21 Blue Ezio (GS Powerup Awards) 54 Breton 22 AC Connor 55 Nord 23 AC Edward 56 High Elf 24 AC Plague Doctor 57 Dovahkiin 25 Kratos 58 6” Alduin 25 Fear Kratos 59 Daedric Warrior 25 Posiedon’s Rage Kratos (NYCC 15) 60 Whiterun Guard (GS) 26 Sackboy 61 Demonic Tyrael 27 P v Z Swashbuckler Zombie 62 Booker De Witt 28 AC Aveline De Grandpre 63 Elizabeth 29 64 Booker De Witt Skyhook 30 Sylvanas 65 6” Big Daddy 31 Thrall 66 Little Sister 32 Deathwing 67 Power Armor Unmasked 32 Gold Deathwing 67 Female Unmasked Power Armor (GS) 33 Murloc 68 Songbird (GS) 33 White Murloc (GS) 69 MSGT Frank Wood (GS) 33 GITD Murloc (ECCC) 69 Muddy MSGT Frank Woods 33 Spectral Murloc (SDCC Blizzard ) 70 Lt Simon “Ghost” Riley (GS) 34 Mur’Ghoul (Blizzard Con) 70 Muddy Lt Simon Ghost Riley 35 AC Arno 71 Brutus (GS) 36 AC Elise 71 Bloody Splattered Brutus 72 Capt John Price (GS) 102 Gold Mega Man (GS) 72 Muddy Capt John Price 103 Rush 73 Jacob Frye 104 Proto Man 74 Evie Frye 105 Dr. -

Resident Evil Director's

RESIDENT EVIL™ DIRECTOR’S CUT DEFAULT CONTROLS START button st art game/pause game/select Status screen directional buttons move character CROSS button open door/attack/talk to characters/ check item SQUARE button (hold) + UP run forwards R1 button draw weapon UP go forwards/ push item LEFT turn left RIGHT turn right DOWN go backwards TRIANGLE button c ancel previous action (on Status screen and Option screen) You can change these controls in the Option screen. Press and hold the R1 button to draw your weapon then use the directional buttons to aim – UP and DOWN moves the weapon up or down; and LEFT or RIGHT moves the weapon left or right. Press the CROSS button to activate the weapon. WEAPONS Your standard equipment includes a 9mm semi-automatic hand gun and a combat knife. There are many other weapons to acquire through your search. Some weapons are more difficult to handle so try them before taking them into combat but don’t waste too many rounds. COMBAT KNIFE A good weapon for a close fight but not nearly as powerful or protective as a firearm. 9MM HAND GUN Popular common hand gun used by many public organizations and armed forces for its high level of reliability. Your gun can hold a clip of 15 bullets maximum. When the clip runs out and you have another, your character will automatically reload. SHOTGUN An excellent hunting gun. It sprays the ammo and is powerful enough to take down fast-moving enemies. It is extremely handy when used at close range. SITUATION New members of Alpha Team arrive in Raccoon City late in the day.