Word & Deed — 07.2 — May 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A JOURNAL of SALVATION ARMY THEOLOGY & MINISTRY Benedictus

Word deed & Vol. X IX No. 1 NOVEMBER 2O16 A JOURNAL OF SALVATION ARMY THEOLOGY & MINISTRY Holiness and Mission: A Salvationist Perspective The New Wonder Memoirs from The Salvation Army’s ‘Outpost War’ in Norway Benedictus: Paul’s Parting Words on Ministry Founders and Foundations: The Legacy of the Booths CREST BOOKS Salvation Army National Headquarters Alexandria, VA, USA WDNov16_Interior_Werk4.indd 1 11/1/16 3:56 PM Word & Deed Mission Statement: The purpose of the journal is to encourage and disseminate the thinking of Salvationists and other Christian colleagues on matters broadly related to the theology and ministry of The Salvation Army. The journal provides a means to understand topics central to the mission of The Salvation Army, integrating the Army’s theology and ministry in response to Christ’s command to love God and our neighbor. Salvation Army Mission Statement: The Salvation Army, an international movement, is an evangelical part of the universal Christian Church. Its message is based on the Bible. Its ministry is motivated by the love of God. Its mission is to preach the gospel of Jesus Christ and to meet human needs in His name without discrimination. Editorial Address: Manuscripts, requests for style sheets, and other correspondence should be addressed to: Lieutenant Colonel Allen Satterlee The Salvation Army, National Headquarters 615 Slaters Lane, Alexandria VA 22313 Phone: 703/684-5500 Fax: 703/684-5539 Email: [email protected] Web: www.sanationalpublications.org Editorial Policy: Contributions related to the mission of the journal will be encouraged, and at times there will be a general call for papers related to specific subjects. -

Download Booklet

Introductions General John Gowans lives on through his words. The Salvation Army on beyond the musicals. The 2015 edition of The Song Book of The world was deeply saddened when he was promoted to Glory in December Salvation Army includes 28 of them – and they continue to be sung 2012, but thank God for the legacy of song words that he left us. Through around the world. them he still speaks to inspire and challenge and encourage, and with this album we are invited to share in a further 23 jewels from this legacy. Commissioner Gisèle Gowans and I were grateful to The International Staff Songsters when the first volume of A Gowans Legacy was recorded It is no secret that I set most of John’s song lyrics to music – and that in 2016. It seems that our appreciation has been shared by many, for explains why all but four of the songs included on this album are with that album has become a best-seller, and we are pleased that it is now music by me. being followed by this second volume. John and I hardly knew each other when in 1966 we were asked to form For my own part, I have enjoyed creating songster arrangements a creative partnership. The National Youth Secretary, Brigadier Denis for a number of the songs on the album for which the original stage Hunter, had called a small group together to discuss the possibility of a arrangement did not lend itself for recording. Getting immersed in that musical for Youth Year 1968 and ideas had flowed. -

Divisional Newsletter - 1212 Decemberdecember 20122012

Divisional Newsletter - 1212 DecemberDecember 20122012 Dear friends, We take this opportunity to thank you for all the extra time and effort you and your people are giving to MAJORS NORM AND ISABEL BECKETT share the true meaning of Christmas. As you proclaim Training Principal and Education Officer, the Christmas message through music, carols and Sweden and Latvia Territory preaching, and share the joy of giving hampers, toys WOODPORT RETIREMENT VILLAGE, NSW and meals, we pray that you will take time to sit in Alison Scott, Captain Jo-Anne Chant, Major wonder at the indescribable love of Christ our Christine Mayes and team Saviour. BURWOOD CORPS, NSW Captain Rhombus Ning and Lieutenants We share with you the words of the following song Marcus and Ji-Sook Wunderlich used at Fairhaven Carols last Sunday night. CAMPBELLTOWN CORPS, NSW When Christ was born the angel voices thundered Majors Garry and Susanne Cox Glory to God and peace to men on earth NAMBUCCA RIVER CORPS, NSW And shepherds in the fields looked on and wondered Captains John and Nicole Viles The marvel of the Saviour’s lowly birth. OASIS YOUTH CENTRE WYONG, NSW When men of wisdom saw a star before them They knew the sign foretold the Saviours birth DECEMBER From lands afar they came in awe to wonder 14 End Queensland School term That God Himself should come to men on earth. 16 Divisional Candidates Farewell 21 End NSW School term 25 Christmas Day That God should come to men, born in a manger 26 Boxing Day I can but ponder such humility JANUARY That He now reigns in glory and in splendour 1 New Years Day I can but wonder of His love for me. -

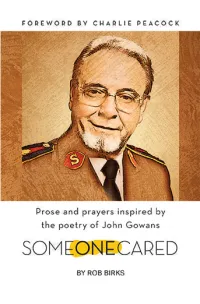

Someone Cared

SOMEONE CARED Prose and Prayers Inspired by the Poetry of John Gowans by Rob Birks SOMEONE CARED Rob Birks 2014 Frontier Press All rights reserved. Except for fair dealing permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this book may be reproduced by any means without written permission from the publisher. Birks, Rob SOMEONE CARED December 2014 Scripture references used in this text are from The Holy Bible, New Inter- national Version, New Living Translation, New American Standard, Ampli- fied Bible, The Living Bible. THE HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION®, NIV® Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.™ Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. The King James Version is public domain in the United States. Scripture taken from The Message. Copyright © 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, 2000, 2001, 2002. Used by permission of NavPress Publishing Group. Copyright © The Salvation Army USA Western Territory ISBN 978-0-9908776-1-5 Printed in the United States For Stacy Sharing poetry introduced our hearts to each other. I couldn’t be more grateful. I love you more than dreams and poetry. More than laughter, more than tears, more than mystery. I love you more than rhythm, more than song I love you more with every breath I draw. —T Bone Burnett iii There is nothing quite like walking through an art gallery with a docent, or the curator himself. This is the feeling I get as I read Ma- jor Robert Birks’ beautiful unveiling of the poetry of John Gowans. He is an informed, inspired guide whose joy regarding the poet’s work is contagious. -

Journal of Aggressive Christianity

JOURNAL OF AGGRESSIVE CHRISTIANITY Issue 81, October – November 2012 Copyright © 2012 Journal of Aggressive Christianity Journal of Aggressive Christianity, Issue 81, October – November 2012 2 In This Issue JOURNAL OF AGGRESSIVE CHRISTIANITY Issue 81, October - November 2012 Editorial Introduction page 3 Editor, Major Stephen Court 100 Most Influential Salvationists page 4 Colonel Richard Munn Holiness and Other Pertinent Matters page 7 Erin Wikle Baptism, Eucharist, and Ministry page 13 Captain Rob Reardon An Innovative Salvation Army page 21 Lieutenant Peter Brookshaw What Now? page 23 Colonel David Gruer Trapped page 29 Tina Laforce A Great Commission? page 38 Lieutenant Xander Coleman How Lost are the Lost? page 42 Major Howard Webber A Living Sacrifice page 44 CSM Tim Taylor What Might Have Been? page 49 Commissioner Wesley Harris William and Catherine Booth's Mobilisation of an Army of all Believers Through Partnered Ministry page 50 Jonathan Evans Journal of Aggressive Christianity, Issue 81, October – November 2012 3 Editorial Introduction by Editor, Major Stephen Court Welcome to JAC81. You might reasonably ask how we can match the weighty JAC80. This is our considered response. Colonel Richard Munn (ICO) updates the first JAC 100 – Most Influential Salvationists list from 2007. This is his personal take on the subject. Soldier Erin Wikle, pioneering a corps in USA Southern Territory, writes Holiness and Other Pertinent Matters. Erin did some very interesting research into holiness and discipleship in the USA Western Territory and shares her results. Captain Rob Reardon (USN) gives his thoughtful take on Baptism, Eucharist, and Ministry from The Salvation Army’s perspective. -

Février 2012 Nouveautés – New Arrivals February 2012

Février 2012 Nouveautés – New Arrivals February 2012 ISBN: 9782070113330 (rel.) ISBN: 2070113337 (rel.) Titre: Écrits gnostiques : la bibliothèque de Nag Hammadi / édition publiée sous la direction de Jean-Pierre Mahé et de Paul-Hubert Poirier ; index établis par Eric Crégheur. Éditeur: [Paris] : Gallimard, c2007. Desc. matérielle: lxxxvii, 1830 p. ; 18 cm. Titre de coll.: (Bibliothèque de la pléiade ; 538) Note générale: "Le présent volume donne la traduction intégrale des quarante-six écrits de Nag Hammadi ... On y a joint ceux du manuscrit copte de Berlin (Berolinensis gnosticus 8502, désigné par BG), ..."--P. xxxi. Note bibliogr.: Comprend des références bibliographiques (p.1685-1689) et des index. AC 20 B5E37M2 2007 ISBN: 9782070771745 (rel.) ISBN: 2070771741 (rel.) Titre: Philosophes confucianistes = Ru jia / textes traduits, présentés et annotés par Charles Le Blanc et Rémi Mathieu. Titre parallèle: Ru jia Éditeur: [Paris] : Gallimard, c2009. Desc. matérielle: lxvi, 1468 p. : cartes ; 18 cm. Titre de coll.: (Bibliothèque de la Pléiade ; 557) Note générale: Contient les "Quatre livres" (Si shu): Lun yu, Mengzi, Da xue et Zhong yong; contient aussi le Classique de la piété filiale (Xiao jing) et le Xun zi. Note bibliogr.: Comprend des références bibliographiques (p. [1335]-1350). Dépouil. complet: Les entretiens de Confucius (Lunyu) - Meng Zi -- La Grande Étude (Daxue) - La pratique équilibrée (Zhongyong) -- Le Classique de la piété filiale (Xiaojing) -- Xun Zi AC 20 B5P45L43 2009 ISBN: 9782130576785 (br.) ISBN: 2130576788 (br.) Auteur: Déroche, François, 1952- Titre: Le Coran / François Déroche. Éditeur: Paris : Presses universitaires de France, 2009. Desc. matérielle: 127 p. ; 18 cm. Titre de coll.: (Que sais-je ; 1245) Note bibliogr.: Comprend des références bibliographiques (p. -

Catherine Booth and World Missions

Word deed & Vol. X XI No. 1 NOVEMBER 2O18 A JOURNAL OF SALVATION ARMY THEOLOGY & MINISTRY Is This the Time? Art and the Army: An Art Historical Perspective Spreading Salvation Abroad: Catherine Booth and World Missions The Salvation Army and the Challenge of Higher Education in the New Millennium CREST BOOKS Salvation Army National Headquarters Alexandria, VA, USA Word & Deed Mission Statement: The purpose of the journal is to encourage and disseminate the thinking of Salvationists and other Christian colleagues on matters broadly related to the theology and ministry of The Salvation Army. The journal provides a means to understand topics central to the mission of The Salvation Army, integrating the Army’s theology and ministry in response to Christ’s command to love God and our neighbor. Salvation Army Mission Statement: The Salvation Army, an international movement, is an evangelical part of the universal Christian Church. Its message is based on the Bible. Its ministry is motivated by the love of God. Its mission Word is to preach the gospel of Jesus Christ and to meet human needs in His name without discrimination. Editorial Address: Manuscripts, requests for style sheets, and other correspondence should be addressed to: & deed A JOURNAL OF SALVATION ARMY Lieutenant Colonel Allen Satterlee THEOLOGY & MINISTRY The Salvation Army, National Headquarters, 615 Slaters Lane, Alexandria VA 22313 Phone: 703/684-5500 Fax: 703/684-5539, [email protected] www.sanationalpublications.org Volume XX • Number 2 MAY 2O18 Volume XXI • Number 1 NOVEMBER 2O18 Editorial Policy: Contributions related to the mission of the journal are encouraged. -

Caminos-De-Gloria.Pdf

“He sido desafiado y ricamente bendecido al leer Caminos de Gloria”. COMISIONADO CARL ELIASEN *** “Estamos endeudados con Enrique Lalut por la forma en que ha dado vida a la historia del Ejército de Salvación en Chile”. GENERAL JOHN LARSSON. (R) *** “La historia es un tema fascinante y cuando se trata de la Obra del Ejército de Salvación en Chile es doblemente fascinante. Enrique Lalut ha usado un estilo que sin duda será bien aceptado no solamente por el pueblo salvacionista, sino por muchos otros. El Ejército de Salvación, en Chile, sigue firme y estoy seguro que este libro hará una contribución fuerte a su misión y ministerio”. COMISIONADO ALEX HUGHES. *** “…contiene reflexiones y comentarios que se aplican dondequiera haya un grupo de hombres y mujeres con “S” en el cuello y un llamado en el corazón”. MAYORA IRIS DE LA ROSA, DOCTORA EN TEOLOGÍA. PUERTO RICO *** “Caminos de Gloria toma aquellos personajes salvacionistas que los años han plasmado en monumentos y los hace caminar, hablar y sentir como nosotros”. PASTOR JUAN J. R. WEHRLI, HISTORIADOR. SANTIAGO CHILE *** “He leído con mucho interés los ocho primeros capítulos de Caminos de Gloria, ellos ciertamente me abren el apetito para anticipar los capítulos restantes, aquellos que completarán la historia del ministerio del Ejército de Salvación en Chile”. COMISIONADO SIegFRED CLAUSEN. *** “Fácil de leer, difícil de olvidar. Su lectura produce lágrimas, sorpresas y carcajadas, pero termina enseñándonos historia”. MAYORA MARTA DEARIN. NUEVA YERSEY USA *** “Quien lea este libro captará el espíritu de sacrificio y devoción de nuestros pioneros. Sin duda, este es un trabajo inspirado por Dios”. -

Introductions

Introductions The proposal to record songs with words by General John Gowans originally came from Commissioner Arthur Thompson (Retired) (former Executive Officer of The International Staff Band). I was We are delighted by this CD featuring songs by John excited at the prospect and delighted to compile a list of tracks, Gowans. The songs bring back a wealth of memories with particular help from General John Larsson (Retired). for both of us. Gisèle was present at the creation of all of these lyrics, so was the first to see and be blessed by Although the intention of this recording is to provide a legacy what John had written. Hearing them again as recorded of songs, it is only a snapshot of the repertoire available and by The International Staff Songsters has been a moving reference is made of other ISS Gowans recordings later in this experience. booklet. I was the next to see most of the lyrics and can still recall The majority of the music included has been composed by the first impact of reading them. But by no means were General John Larsson; however, other composers have been all of John’s words destined to be Gowans and Larsson featured and my particular thanks go to Matt Woods and Neil songs; some of his best-loved words are sung to the Smith for sharing a new setting, by Mark Hayes, of You can’t traditional tune of Bethany, and composers Ivor Bosanko stop God from loving you, which was commissioned for the USA and Richard Phillips have also partnered with him. -

Order Form to Be Read in Weekly (1955) Gives Brief Studies in Their Insight, Honesty and £4.95 Theological and Practical Gatherings of Salvationists

GENERAL PUBLICATIONS Catalogue 2013-2014 Salvation Books is the book publishing imprint of International Headquarters and aims to publish around six titles per year. Here you can browse through the various titles and purchase them as printed copies CLASSIC SALVATIONIST TEXTS General Wickberg – What A Hope! No Heart More Tender General Wahlström – From Her Heart Called Up Gilbert Ellis Harry Read A Pilgrim’s Song Helen Clifton Autobiography of Erik In a series of short, Based on his experiences Autobiography of Jarl Chosen by her husband, Wickberg – the ninth manageable chapters, of bereavement following Wahlström – the twelfth General Shaw Clifton General of The Salvation Lieut-Colonel Gilbert Ellis the death of his wife, General of The Salvation (Rtd), this compilation Army. The book gives a explores different facets Commissioner Read has Army. Explores in detail represents writings from fascinating account of of hope. Using illustrations penned this collection how, as one of God’s almost every phase of his life, including his role from life in a down-to- of poems and reflections pilgrims, he was uniquely Commissioner Helen An Adventure Shared The Common People’s The Desert Road To Glory Essentials Of Christian Practical Religion as liaison officer during earth manner, the author that combine tenderness privileged to witness the Clifton’s influential service Catherine Baird Gospel Clarence Wiseman Experience Catherine Booth the years of the Second brings new insights via his and sensitivity with work of The Salvation Army as a Salvation Army Originally published in Gunpei Yamamuro Originally published in Frederick Coutts The chapters of this book World War. -

Free Download

If you want to be inspired and feel good about life and the Army, just sit down for a moment with John Bate and listen to him as he tells of the amazing adventures he has had in the Lord’s service. He makes the events come alive, his sense of fun and zest for life lift the spirit, and his sensitive insights warm the heart. I know, for I have often been there myself. And now all of that potential for enjoyment and uplift is right here in the pages of Destination Unknown for every reader to share. Marvelous! —JOHN LARSSON General (Ret.) This remarkable book is an example of history alive! Written by the indomitable Colonel John Bate, who wrote in the preface that he gratefully accepted what God had provided and was excited about it, those who know this author will acknowledge that he still lives by that spiritual rule of life. This is not a book about Salvation Army leaders with whom John and Val Bate were associated, but a book about the unfolding of the life and ministry of leaders in the Army whom the Bates knew well and served well, all in the spirit of the servant leadership of which our Lord was the supreme example. This is also a book about the many faces of our shared human experiences lived out for the sake of the kingdom of God. The author skilfully takes the reader through the range of human emotion from pathos to hilarity, depending on the situations in which God had place him and his wife as their own leadership abilities were recognized by the Army. -

The Salvation Army

SALVATIONIST Essential reading for everyone linked to The Salvation Army// www.salvationarmy.org.uk/salvationist 5 January 2013 // No. 1379 // Price 60p // Also available digitally Pages 14 and 15 CONTENTS 3. FROM THE EDITOR 4. NEW YEAR QUIZ Quiz questions and picture caption 12. & 13. competition results 1. 2. 3. 5. 11. NEWS 5. 6. 4. Nottingham William Booth Memorial Halls // Camborne // Winton // Jarrow // USA Eastern // 16. 17. 18. 19. 7. Sherburn Hill // William Booth 1. Heilsarmee enters the Eurovision Song Contest representing Switzerland, and secures their place in Malmö, Sweden 2. Bands from across the territory welcome Olympic athletes and spectators at Heathrow Airport 3. General Linda Bond receives £50,000 for development work in Africa from College // Papua New Guinea // the proceeds of ISB120 4. Torchbearer Major Val Mylechreest and Lieut-Colonel Ivor Telfer carry an Olympic torch through THQ 5. The territory launches Portraits – A Month In The Life Of The Salvation Army 6. Commissioners André and Silvia Cox meet silver medalist Nino Schurter of Switzerland at Hadleigh Farm 7. Youth at Northern Summer School enjoy Jubilee night 8. The Territorial Youth Choir enthusiastically participate at The Lighthouse, Poole 9. The Disciples of the Cross Session are publicly welcomed as they begin their training at William Booth College 10. The European Congress in Prague concludes with flag waving 11. World of Brass hosts a festival featuring RSA’s music to celebrate his 90th birthday 12. Commissioners André and Silvia Cox are welcomed as territorial leaders 13. Graduates gather in the assembly hall during SISTAD awards day to celebrate their achievements 14.