Use of Stellate Ganglion Block for Refractory Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: a Review of Published Cases Maryam Navaie1*, Morgan S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review of Sympathetic Blocks Anatomy, Sonoanatomy, Evidence, and Techniques

CHRONIC AND INTERVENTIONAL PAIN REVIEW ARTICLE Review of Sympathetic Blocks Anatomy, Sonoanatomy, Evidence, and Techniques Samir Baig, MD,* Jee Youn Moon, MD, PhD,† and Hariharan Shankar, MBBS*‡ Search Strategy Abstract: The autonomic nervous system is composed of the sympa- thetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. The sympathetic nervous sys- We performed a PubMed and MEDLINE search of all arti- tem is implicated in situations involving emergent action by the body and cles published in English from the years 1916 to 2015 using the “ ”“ ”“ additionally plays a role in mediating pain states and pathologies in the key words ultrasound, ultrasound guided, sympathetic block- ”“ ”“ body. Painful conditions thought to have a sympathetically mediated com- ade, sympathetically mediated pain, stellate ganglion block- ”“ ” “ ” ponent may respond to blockade of the corresponding sympathetic fibers. ade, celiac plexus blockade, , lumbar sympathetic blockade, “ ” “ ” The paravertebral sympathetic chain has been targeted for various painful hypogastric plexus blockade, and ganglion impar blockade. conditions. Although initially injected using landmark-based techniques, In order to capture the breadth of available evidence, because there fluoroscopy and more recently ultrasound imaging have allowed greater were only a few controlled trials, case reports were also included. visualization and facilitated injections of these structures. In addition to There were an insufficient number of reports to perform a system- treating painful conditions, sympathetic blockade has been used to improve atic review. Hence, we elected to perform a narrative review. perfusion, treat angina, and even suppress posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. This review explores the anatomy, sonoanatomy, and evidence DISCUSSION supporting these injections and focuses on ultrasound-guided/assisted tech- nique for the performance of these blocks. -

Stellate Ganglion Block

Stellate Ganglion Block Pain Management 682-885 -7246 1500 Cooper Street How we give the block Fort Worth, Texas 76104 Takes approximately 15 to 20 minutes Stellate Ganglion 1. We start an IV and give medicine to relax. 2. You lie on your back on the x-ray table. Group of nerves in neck, next to the spine. 3. We clean the skin on your neck to help • Part of larger system of nerves called decrease chance of infection. “autonomic nervous system”. 4. Doctor injects small area with numbing medicine. • These nerves help control the size of blood 5. Imaging guides your doctor during the vessels that flow to the arms, head, and neck. injection. • These nerves may also send pain signals from the head, neck, or arms. Please know: You should not have this procedure if you: Stellate Ganglion Block Used for treating and 1. Have allergies to any x-ray dye, seafood, Lasix, diagnosing a number of or any of the medicines we may inject. painful conditions in the 2. Are on a blood thinning medicine such as face, neck, and arms. Coumadin, heparin, or Lovenox. 3. Have an active infection. 4. Have a temperature over 101 degrees. 5. Have a low platelet count. Medical Illustration(s) © 2019 Nucleus Medical Media, Inc. How the block helps Risks Generally speaking, this procedure is safe. • Injection blocks messages sent by the nerves. However, like any procedure there are risks, side • If these nerves are sending the pain signals, effects, and the possibility of complications. the pain will be reduced after the injection. -

Stellate Ganglion) and Lumbar Sympathetic Nerve Blocks

CERVICAL (STELLATE GANGLION) AND LUMBAR SYMPATHETIC NERVE BLOCKS What are sympathetic nerves and why is a sympathetic nerve block helpful? The sympathetic nervous system is part of the autonomic nervous system which controls functions like blood flow to the extremities, sweating, heart rate, digestion, blood pressure, goose bumps and many other functions. In other words, the autonomic nervous system is responsible for controlling things you do not think about or have direct control over. Sometimes arm or leg pain is caused by a malfunction of the sympathetic nervous system secondary to an injury. A sympathetic nerve block involves injecting anesthetic (numbing) medication around the sympathetic nerves which are located in front of the spinal column. By doing this, the system is temporarily blocked in hopes of reducing or eliminating your pain. If the initial block is successful temporarily, then additional blocks can be repeated every 7-10 days in order to relieve your pain more permanently. What happens during the procedure? You will lie on an x-ray table, on your back for a cervical block and on your side for a lumbar block. The physician will use fluoroscopic (x-ray) guidance to visualize the area where the sympathetic nerves lie. The physician will scrub your skin with sterile soap and place a drape on your neck or back. The physician will numb a small area of skin with anesthetic medication. The physician will direct a very small needle using fluoroscopic guidance towards the sympathetic nerves. The physician will inject a small amount of contrast (dye) to insure proper needle position and then a small amount of anesthetic around the nerve. -

Morphology of Sympathetic Chain in Saguinus Niger

Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências (2013) 85(1): 365-370 (Annals of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences) Printed version ISSN 0001-3765 / Online version ISSN 1678-2690 www.scielo.br/aabc Morphology of sympathetic chain in Saguinus niger MARINA P.E. PINTO1, ÉRIKA BRANCO1, EMERSON T. FIORETTO2, LUIZA C. PEREIRA3 and ANA R. LIMA1 1Universidade Federal Rural da Amazônia (UFRA), Instituto de Saúde e Produção Animal – ISPA, Faculdade de Medicina Veterinária, Avenida Perimetral, 2501, Belém, PA, Brasil 2 Universidade Federal de Sergipe (UFS), Cidade Universitária Professor José Aloísio de Campos, Avenida Marechal Rondon, s/n, Jardim Rosa Elze, São Cristovão, Aracajú, SE, Brasil 3 Empresa Hydro LTDA, Mina de Bauxita – Paragominas, PA, Brasil Manuscript received on March 20, 2012; accepted for publication on October 2, 2012 ABSTRACT Saguinus niger popularly known as Sauim, is a Brazilian North primate. Sympathetic chain investigation would support traumatic and/or cancer diagnosis which are little described in wild animals. The aim of this study was to describe the morphology and distribution of sympathetic chain in order to supply knowledge for neurocomparative research. Three female young animals that came death by natural causes were investigated. Animals were fixed in formaldehyde 10% and dissected along the sympathetic chain in neck, thorax and abdomen. Cranial cervical ganglion was located at the level of carotid bifurcation, related to carotid internal artery. In neck basis the vagosympathetic trunk divides into the sympathetic trunk and the parasympathetic vagal nerve. Sympathetic trunk ran in dorsal position and originated the stellate ganglia, formed by the fusion of caudal cervical and first thoracic ganglia. -

Detection of the Stellate and Thoracic Sympathetic Chain Ganglia with High-Resolution 3D-CISS MR Imaging

ORIGINAL RESEARCH SPINE Detection of the Stellate and Thoracic Sympathetic Chain Ganglia with High-Resolution 3D-CISS MR Imaging X A. Chaudhry, X A. Kamali, X D.A. Herzka, X K.C. Wang, X J.A. Carrino, and X A.M. Blitz ABSTRACT BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: Despite the importance of the sympathetic nervous system in homeostasis and its putative role in various disease states, little is known regarding our ability to image the sympathetic chain and sympathetic chain ganglia, perhaps owing to their small size. In this retrospective study, we sought to evaluate the normal anatomy of the sympathetic chain ganglia and assess the detectability of the sympathetic chain and sympathetic chain ganglia on high-resolution 3D-CISS images. MATERIALS AND METHODS: This study included 29 patients who underwent 3D-CISS MR imaging of the thoracic spine for reasons unrelated to abnormalities of the sympathetic nervous system. Patients with a prior spinal operation or visible spinal pathology were excluded. The sympathetic chain ganglia were evaluated using noncontrast 3D-CISS MR imaging. Statistical analyses included t tests and measures of central tendency. The Cohen statistic was calculated to evaluate interrater reliability. RESULTS: The stellate ganglion and thoracic chain ganglia were identified in all subjects except at the T10–T11 and T11–T12 levels. The stellate ganglion was found inferomedial to the subclavian artery and anterior and inferior to the transverse process of C7 in all subjects. Thoracic sympathetic chain ganglia were identified ventral to the costovertebral junction in all subjects from T2 to T10. There was strong interobserver agreement for the detection of the sympathetic chain ganglia with Ͼ 0.80. -

256 Stellate Ganglion Block

Sign up to receive ATOTW weekly - email [email protected] STELLATE GANGLION BLOCK ANAESTHESIA TUTORIAL OF THE WEEK 256 26TH MARCH 2012 Dr Vishal Thanawala, Specialist registrar, Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust, Nottingham, United Kingdom. Dr Jatin Dedhia, Consultant in Anaesthesia and Pain medicine, United Lincolnshire Hospitals NHS Trust, Lincoln, United Kingdom. Correspondence to [email protected] QUESTIONS Before continuing, try to answer the following questions. The answers can be found at the end of the article, together with an explanation. 1) Regarding the anatomy of the stellate ganglion: a) It receives contribution from the first thoracic ganglion b) It is situated anterior to the transverse process of C7 c) It supplies sympathetic efferent fibres to the hand, neck, head and heart d) The ganglion lies superiorly and posterior to the dome of the pleura e) The vertebral artery lies lateral the ganglion 2) Stellate ganglion block is useful in the treatment of : a) Thrombo-angitis obliterans b) Refractory angina c) Phantom limb pain d) Migraine e) Scleroderma 3) Possible complications of stellate ganglion block are: a) Pneumothorax b) Oesophageal perforation c) Seizures d) Mydriasis e) Tachycardia INTRODUCTION The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) directly controls involuntary human homeostatic activities and has a major role in neuropathic, vascular, and visceral pain. Sympathetically maintained pain occurs in a variety of vascular pathologies such as occlusive arterial diseases, diabetes mellitus or venous ulceration and neuropathic conditions such as complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), postherpetic neuralgia and after peripheral nerve lesion. CRPS type I (formerly known as reflex sympathetic dystrophy) occurs following an initiating event such as trauma or injury but with little or no nerve injury while CRPS Type II (formerly causalgia) has nerve injury as its causative factor. -

Transcriptomic and Neurochemical Analysis of the Stellate Ganglia in Mice Highlights Sex Diferences Received: 17 January 2018 R

www.nature.com/scientificreports Corrected: Publisher Correction OPEN Transcriptomic and neurochemical analysis of the stellate ganglia in mice highlights sex diferences Received: 17 January 2018 R. G. Bayles1, A. Olivas1, Q. Denfeld 1, W. R. Woodward1, S. S. Fei2, L. Gao2 & B. A. Habecker 1 Accepted: 31 May 2018 The stellate ganglia are the predominant source of sympathetic innervation to the heart. Remodeling Published: 12 June 2018 of the nerves projecting to the heart has been observed in several cardiovascular diseases, however studies of adult stellate ganglia are limited. A profle of the baseline transcriptomic and neurochemical characteristics of the stellate ganglia in adult C57Bl6j mice, a common model for the study of cardiovascular diseases, may aid future investigations. We have generated a dataset of baseline measurements of mouse stellate ganglia using RNAseq, HPLC and mass spectrometry. Expression diferences between male and female mice were identifed. These diferences included physiologically important genes for growth factors, receptors and ion channels. While the neurochemical profles of male and female stellate ganglia were not diferent, minor diferences in neurotransmitter content were identifed in heart tissue. Te majority of sympathetic nerves projecting to the heart originate in the stellate ganglia, with innervation provided throughout the heart from both the lef and right ganglion1. Coronary artery diseases, and their conse- quences such as acute myocardial infarction, cause alterations in cardiac neuronal function, which can contribute to the development of heart failure and cardiac arrhythmias2. Developing new therapeutic strategies to target peripheral sympathetic transmission will require a better understanding of the neural remodeling that occurs in disease, which is based on our characterization and understanding of the baseline physiology. -

The Anatomy of Spinal Sympathetic Structures in the Cat

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1978 The Anatomy of Spinal Sympathetic Structures in the Cat Kyungsoon Chung Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Anatomy Commons Recommended Citation Chung, Kyungsoon, "The Anatomy of Spinal Sympathetic Structures in the Cat" (1978). Dissertations. 1725. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/1725 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1978 Kyungsoon Chung ; THE ANATOMY OF SPINAL SYMPATHETIC STRUCTURES IN THE CAT by Kyungsoon Chung A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillemnt of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 1978 Dedicated to my parents, Mom and Dad ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere appreciation to my adviser, Dr. Faith LaVelle, who gave unsparingly of her time and energy to assist in the fruition of this study. The guidance and comments of Dr. Robert Wurster throughout this study were specially appreciated. I would like to thank the faculty of the Depart- ment of Anatomy for giving me a chance for graduate study and for molding me as a scientist. This dissertation would not have been possible without the help and understanding of my husband and colleague, Jin Mo. -

Stellate Ganglion Blockade: an Intervention for the Management of Ventricular Arrhythmias

Current Hypertension Reports (2020) 22:100 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-020-01111-8 DEVICE-BASED APPROACHES FOR HYPERTENSION (M SCHLAICH, SECTION EDITOR) Stellate Ganglion Blockade: an Intervention for the Management of Ventricular Arrhythmias Arun Ganesh1 & Yawar J. Qadri2 & Richard L. Boortz-Marx1 & Sana M. Al-Khatib3 & David H. Harpole Jr4 & Jason N. Katz3 & Jason I. Koontz3,7 & Joseph P. Mathew1 & Neil D. Ray1 & Albert Y. Sun3 & Betty C. Tong4 & Luis Ulloa1,5 & Jonathan P. Piccini3,6,7 & Marat Fudim3,6 Accepted: 25 September 2020 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2020 Abstract Purpose of Review To highlight the indications, procedural considerations, and data supporting the use of stellate ganglion blockade (SGB) for management of refractory ventricular arrhythmias. Recent Findings In patients with refractory ventricular arrhythmias, unilateral or bilateral SGB can reduce arrhythmia burden and defibrillation events for 24–72 h, allowing time for use of other therapies like catheter ablation, surgical sympathectomy, or heart transplantation. The efficacy of SGB appears to be consistent despite the type (monomorphic vs polymorphic) or etiology (ischemic vs non-ischemic cardiomyopathy) of the ventricular arrhythmia. Ultrasound-guided SGB is safe with low risk for complications, even when performed on anticoagulation. Summary SGB is effective and safe and could be considered for patients with refractory ventricular arrhythmias. Keywords Stellate ganglion block . Ventricular arrhythmia . Ventricular tachycardia . Ventricular fibrillation Introduction over 450,000 deaths every year in the USA [2]. Electrical storm is a particularly challenging clinical entity in which Ventricular tachycardia (VT) and fibrillation (VF) are life- VT/VF events recur frequently (3 or more episodes of threatening arrhythmias with an increasing prevalence [1]. -

Sympathetic Chain – Cervical Part

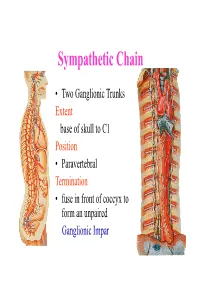

Sympathetic Chain • Two Ganglionic Trunks Extent base of skull to C1 Position • Paravertebral Termination • fuse in front of coccyx to form an unpaired Ganglionic Impar Sympathetic Chain •3 Ganglia in cervical part •11Ganglia in thoracic Part •4 lumbar Ganglia •4 Sacral ganglia Sympathetic Chain-cervical part • lie Behind Carotid Sheath and • in front of Longus colli & Longus Capitis muscles • Initially no. of Sympathetic ganglia correspond to no. of Spinal Nerves • Later • Superior formed by fusion of upper 4 cervical Ganglia • Middle by 5th and 6th •Inferiorby joining of 7th and 8th cervical ganglia Sympathetic Chain – Cervical Part • Cervical Part Ganglia Superior Cervical ganglia Middle Cervical Ganglia Inferior Cervical ganglia Sometimes Inferior cervical and first Thoracic fuse to form a Cervico-Thoracic or Stellate Ganglia Sympathetic Chain – Cervical Part • Do not receive white rami communicantes from cervical spinal segments • LAT. HORN CELLS OF T1-T5 PROVIDE PRE- GANGLIONIC FIBRES • Gives grey rami communicantes to all 8 cervical nerves Sympathetic Chain – Cervical Part • GANGLION • Contains-multipolar post ganglionic neurons & few interneurons (chromaffin or SIF cells*) • *modulate activities of post ganglionic neurons by dopamine • SYMPATHETIC TRUNK conveys pre & post ganglionic motor & sensory fibres between ganglia SUPERIOR CERVICAL GANGLION • Largest ,fusiform, 2.5cm length • Fuses upper four cervical ganglia • Situation- opposite C2 &C3 Vertebrae behind ICA& infont of l. capitis • Receives pre ganglionic fibres mostly from upper three thracic segments • BRANCHES (all convey post ganglionic fibres & some sensory fibres) SUPERIOR CERVICAL GANGLION • BRANCHES • Lateral-grey rami comm. to C1- C4 nerves &(C5-C8) • Medial-laryngo-pharyngeal - cardiac(no pain fibr.) Anterior-ramify around CCA,ECA & its branches Ascending-INTERNAL CAROTID NERVE -carotido-tympanic -deep petrosal -communicating(v,iii,iv,v,&vi) -nervus conarii (pineal gland) Term.communicating(ant. -

Thoracoscopic Sympathectomy: Techniques and Outcomes

Neurosurg Focus 4 (2):Article 4, 1998 Thoracoscopic sympathectomy: techniques and outcomes J. Patrick Johnson, M.D., Samuel S. Ahn, M.D., William C. Choi, M.D., Jeffery E. Masciopinto, M.D., Kee D. Kim, M.D., Aaron G. Filler, M.D., and Antonio A. F. DeSalles, M.D. Divisions of Neurosurgery and Vascular Surgery, Department of Surgery, School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California; and Department of Neurological Surgery, Montreal Neurological Institute, Montreal, Quebec, Canada Thoracic sympathectomy is an important option in the treatment of palmar hyperhidrosis and pain disorders. Earlier surgical procedures were highly invasive with known morbidity, acceptable outcome, and established recurrence rates that were the limitations to considering surgical treatment. Thoracoscopic sympathectomy is a minimally invasive procedure that allows detailed visualization of the sympathetic ganglia and minimal postoperative morbidity; however, outcome studies of this technique have been limited. The authors treated 39 patients with 60 thoracoscopic procedures, and the outcomes in this small series were equivalent to previously established open surgical techniques; however, operative moribidity rates, hospital stay, and time of return to normal activity were substantially reduced. Complications and recurrence of symptoms were also comparable to previous reports. Overall patient satisfaction and willingness to repeat the operative procedure ranged from 66 to 96% in all patients. Patients and physicians can consider minimally invasive thoracoscopic sympathectomy procedures as an option to treat sympathetically mediated disorders because of the procedure's reduced morbidity and at least equivalent outcome rates in comparison to other treatments. Key Words * thoracoscopic sympathectomy * sympathetic ganglia * endoscopy Thoracoscopic sympathectomy is performed using minimally invasive endoscopic techniques first described by Kux[17] in 1951 for the treatment of hyperhidrosis. -

Vertebral Arteries Bilaterally Passing Through Stellate (Cervicothoracic) Ganglion B

Folia Morphol. Vol. 79, No. 3, pp. 621–626 DOI: 10.5603/FM.a2019.0115 C A S E R E P O R T Copyright © 2020 Via Medica ISSN 0015–5659 journals.viamedica.pl Vertebral arteries bilaterally passing through stellate (cervicothoracic) ganglion B. Chaudhary1, P.R. Tripathy2, M.R. Gaikwad2 1All India Institute of Medical Science, Patna, India 2All India Institute of Medical Science, Bhubaneswar, India [Received: 27 August 2019; Accepted: 5 October 2019] Vertebral artery is a branch of the first part of subclavian artery. Vertebral artery arising from the aortic arch most commonly presents on the left side. The cervical part of sympathetic trunk is closely related to the vertebral artery in the cervical region. Though lots of variations regarding anomalous origin, course of vertebral artery is reported in the literature, here we present a rare anomaly in which ver- tebral artery after originating from aortic arch is passing through stellate ganglia and it enters into the transverse foramina of higher cervical vertebra (C5). Such variation should be kept in mind by anaesthetist during stellate ganglion block in order to relieve intractable pain in central nervous system lesion. Surgeons should keep this anomaly in mind during cervical spine surgery otherwise vertebral artery may get injured leading to haemorrhage. (Folia Morphol 2020; 79, 3: 621–626) Key words: aortic arch, haemodynamic, Horner syndrome, sympathetic ganglia, vertebral artery INTRODUCTION hemisphere [15]. It is divided into four segments. The In normal anatomy of aortic arch and its great first segment (V1) extends from its origin up to its vessels, vertebral artery (VA) arises from the first part entry into C6 transverse foramen, the second part (V2) of subclavian artery (SA).