The Victoria Cross Garden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The London Gazette, July 23, 1907. 5031

THE LONDON GAZETTE, JULY 23, 1907. 5031 ' War Office, Whitehall, The Loyal North Lancashire Regiment, Lieutenant 23rd July, 1907. George M. Reynell is seconded for service in CAVALRY OP THE LINE. the Army Service Corps. Dated 1st July, 5th {Princess Charlotte of Wales's) Dragoon 1907. Guards, Supernumerary Captain John Norwood, Princess Louise's {Argyll and Sutherland High- V.C., to be Captain in succession to Major landers), Major and Brevet Colonel John G. W. Q. Winwood, D.S.O., who holds a Staff Wolrige-Gordon retires on retired pay. Dated appointment. Dated 1st June, 1907. 24th July, 1907, 6th, Dragoon Guards (Cardbiniers), Lieutenant ARMY MEDICAL SERVICE. Kenneth T. Ridpath is seconded for service on the Staff. Dated 28th June, 1907. Royal Army Medical Corps, LieutenanfcColonel Edwin 0. Milward is placed on retired pay. ROYAL REGIMENT OF ARTILLERY. Dated 24th July, 1907. Royal Horse and Royal Field Artillery, Lieu- MEMORANDA. tenant-Colonel and Brevet Colonel Richard F. McCrea is placed on half-pay. Dated 21st Lieutenant-Colonel and Brevet Colonel Arthur July, 1907. C. Daniell, half-pay, retires on retired pay. Major Robert A. Vigne to be Lieutenant-Colonel, Dated 24th July, 1907. vice R. F. McCrea. Dated 21st July, 1907. Lieutenant-Colonel Frederick J. Tobin, D.S.O., Supernumerary Captain Henry M. Drake to be The Royal Irish Rifles, to be Brevet Colonel. Captain, vice H. E. Street, appointed Adjutant. Dated 21st July, 1907. Dated 3rd July, 1907. Lieutenant-Colonel Rowan H. L. Warner, Lieutenant Hugh R. S. Massy is seconded for half-pay, retires on retired pay. Dated 24th service under the Colonial Office. -

Chapter Iv Findings and Discussion

CHAPTER IV FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION The present chapter deals with the result of the research which is divided into two parts namely findings and discussion. In the first part, the researcher reveals the examined data from The Duchess and The Young Victoria movies. It shows the data of negative politeness strategies implemented in those movies and the factors affecting the use of negative politeness strategies employed by main characters in those British movies. In the discussion part, the researcher explores the detailed explanation related to the formulation problems which have been explained in Chapter I. A. Research Findings According to the process of collecting and analysing the data, there are 42 data of negative politeness strategies implemented by the main characters in The Duchess and The Young Victoria movies. The findings are presented in Table 4 and Table 5. 52 TABLE 4. FINDINGS ON NEGATIVE POLITENESS IN THE DUCHESS MOVIE Realizations of Negative Factors Politeness Strategies Circumstances Negative Politeness No Strategies tance H’s Frequency Payoff Be Direct Be Percentage (%) Don’t Coerce Don’t Presume Percentage (%) to H on not impinge Social Dis Relative Power Percentage (%) Percentage Redress other wants ofRedress Communicate S’s want CommunicateS’s want Rankof Imposition Be conventionally 1 2 10 % 1 0 1 0 0 1 7,69% 0 0 1 10 % indirect 2 Question, Hedge 8 40 % 0 5 3 0 0 8 61,54% 1 0 0 10 % 3 Be Pessimistic 1 5 % 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 % 0 1 0 10 % Minimize the 4 3 15 % 0 0 3 0 0 2 15,38% 0 0 1 10 % imposition 5 Give deference 1 5 % 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 % 0 0 1 10 % 6 Apologize 1 5 % 0 0 0 1 0 1 7,69% 0 1 0 10 % Impersonalize speaker 7 1 5 % 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 % 0 0 1 10 % and hearer State the FTA as 8 1 5 % 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 % 0 1 0 10 % general rule 9 Nominalize 1 5 % 0 0 0 1 0 1 7,69 % 1 0 0 10 % Go on record as 10 1 5 % 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 % 0 0 1 10 % incurring debt Total 20 100% 1 5 8 4 2 13 100 % 2 3 5 100% Table 4 presents the data related to negative politeness strategies, realizations and factors affecting the main character in The Duchess movie. -

The London Gazette, 25 March, 1930. 1895

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 25 MARCH, 1930. 1895 panion of Our Distinguished Service Order, on Sir Jeremiah Colman, Baronet, Alfred Heath- whom we have conferred the Decoration of the cote Copeman, Herbert Thomas Crosby, John Military Cross, Albert Charles Gladstone, Francis Greenwood, Esquires, Lancelot Wilkin- Alexander Shaw (commonly called the Honour- son Dent, Esquire, Officer of Our Most Excel- able Alexander Shaw), Esquires, Sir John lent Order of the British Empire, Edwin Gordon Nairne, Baronet, Charles Joeelyn Hanson Freshfield, Esquire, Sir James Hambro, Esquire, Sir Josiah Charles Stamp, Fortescue Flannery, Baronet, Charles John Knight Grand Cross of Our Most Excellent Ritchie, Esquire, Officer of Our Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, Sir Ernest Mus- Order of the British Empire; OUR right trusty grave Harvey, Knight Commander of Our and well-beloved Charles, Lord Ritchie of Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, Dundee; OUR trusty and well-beloved Sir Sir Basil Phillott Blackett, Knight Commander Alfred James Reynolds, Knight, Percy Her- of Our Most Honourable Order of the Bath, bert Pound, George William Henderson, Gwyn Knight Commander of Our Most Exalted Order Vaughan Morgan, Esquires, Frank Henry of the Star of India, Sir Andrew Rae Duncan, Cook, Esquire, Companion of Our Most Knight, Edward Robert Peacock, James Lionel Eminent Order of the Indian Empire, Ridpath, Esquires, Sir Homewood Crawford, Frederick Henry Keeling Durlacher, Esquire, Knight, Commander of Our Royal Victorian Colonel Sir Charles Elton Longmore, Knight Order; Sir William Jameson 'Soulsby, Knight Commander of Our Most Honourable Order of Commander of Our Royal Victorian Order, the Bath, Colonel Charles St. -

The Journal of the Orders and Medals Research Society

Ind ex to The Journal of the Orders and Medals Research Society Volume 47 2008 No. 1-4 Campaign Medals are dated as in Medals: The Researcher’s Guide, by William Spencer 2006, The National Archives, Kew. Journal entries are indexed as Volume (Part 1-4) page number(s): eg 47(1) 39 50th (Queen' s Own) Regiment, Punniar Star 1843 Beaumont, Sub -Lieutenant Spencer W M, RN 47(2) 84-91 47(3) 193-4 19I4 Star, origin and design ............................... 47(2) 126 Beavis, Fred, Polish Airmen of the Battle of Britain 1914- I5 Star, origin and design .............................. 47(2) 126 47(4) 263-7 2008 New Years Honours Lis t, numbers ............... 47(1) 43 Beighton, Professor Peter, Blackpool Special Constabulary 1914 -1918: Gold medals and Insignia Adria SS (Italian freighter 1918) .................. 47(3) 165-7 47 (1) 24-8 Africa General Service Medal 1902-56, to East Africa Bendry, Simon, Military Medal, Kinnem, Serjeant Rifles unnamed ........................................... 47(3) 190-1 William, RGA TF ..................................... 47(3) 189-90 African Police Medal for Meritorious Service I 915-38 Beswick, Nicholas, Long Service and Good Conduct 47(1) 12-18 Medals, criteria for ......................................... 47(4) 255 Albert Medal, Beech in g, Sick Berth Attendant George, Birmingham Police Total Abstinence Medal ........ 47(2) 122 HMS Ibis ........................................................... 47(1) 5 Blackpool Special Constabulary 1914- 1918, Gold Alguada Reef Lighthouse ............................... 47(4) 251-4 medals and Insignia ...................................... 47(1) 24-8 Allen, Anthony, African Police Medal for Meritorious Blonde, HMS (5th rate 38, 1805) ......................... 47(3) 1 88 Service 1915-38 ........................................... 47(1) 12-1 8 British Empire, Order of the, CBE, Cornioley, Mme Pearl, Arandora Star (cruise liner 1927) ..................... -

A Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2002 A Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays. Bonny Ball Copenhaver East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Copenhaver, Bonny Ball, "A Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays." (2002). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 632. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/632 This Dissertation - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays A dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Education in Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis by Bonny Ball Copenhaver May 2002 Dr. W. Hal Knight, Chair Dr. Jack Branscomb Dr. Nancy Dishner Dr. Russell West Keywords: Gender Roles, Feminism, Modernism, Postmodernism, American Theatre, Robbins, Glaspell, O'Neill, Miller, Williams, Hansbury, Kennedy, Wasserstein, Shange, Wilson, Mamet, Vogel ABSTRACT The Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays by Bonny Ball Copenhaver The purpose of this study was to describe how gender was portrayed and to determine how gender roles were depicted and defined in a selection of Modern and Postmodern American plays. -

History 1886

How many bones must you bury before you can call yourself an African? Updated December 2009 A South African Diary: Contested Identity, My Family - Our Story Part D: 1886 - 1909 Compiled by: Dr. Anthony Turton [email protected] Caution in the use and interpretation of these data This document consists of events data presented in chronological order. It is designed to give the reader an insight into the complex drivers at work over time, by showing how many events were occurring simultaneously. It is also designed to guide future research by serious scholars, who would verify all data independently as a matter of sound scholarship and never accept this as being valid in its own right. Read together, they indicate a trend, whereas read in isolation, they become sterile facts devoid of much meaning. Given that they are “facts”, their origin is generally not cited, as a fact belongs to nobody. On occasion where an interpretation is made, then the commentator’s name is cited as appropriate. Where similar information is shown for different dates, it is because some confusion exists on the exact detail of that event, so the reader must use caution when interpreting it, because a “fact” is something over which no alternate interpretation can be given. These events data are considered by the author to be relevant, based on his professional experience as a trained researcher. Own judgement must be used at all times . All users are urged to verify these data independently. The individual selection of data also represents the author’s bias, so the dataset must not be regarded as being complete. -

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France. -

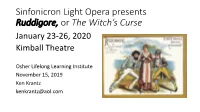

Krantz [email protected] Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia + Delta Omicron = Sinfonicron G&S Works, with Date and Length of Original London Run • Thespis 1871 (63)

Sinfonicron Light Opera presents Ruddigore, or The Witch’s Curse January 23-26, 2020 Kimball Theatre Osher Lifelong Learning Institute November 15, 2019 Ken Krantz [email protected] Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia + Delta Omicron = Sinfonicron G&S Works, with date and length of original London run • Thespis 1871 (63) • Trial by Jury 1875 (131) • The Sorcerer 1877 (178) • HMS Pinafore 1878 (571) • The Pirates of Penzance 1879 (363) • Patience 1881 (578) • Iolanthe 1882 (398) G&S Works, Continued • Princess Ida 1884 (246) • The Mikado 1885 (672) • Ruddigore 1887 (288) • The Yeomen of the Guard 1888 (423) • The Gondoliers 1889 (554) • Utopia, Limited 1893 (245) • The Grand Duke 1896 (123) Elements of Gilbert’s stagecraft • Topsy-Turvydom (a/k/a Gilbertian logic) • Firm directorial control • The typical issue: Who will marry the soprano? • The typical competition: tenor vs. patter baritone • The Lozenge Plot • Literal lozenge: Used in The Sorcerer and never again • Virtual Lozenge: Used almost constantly Ruddigore: A “problem” opera • The horror show plot • The original spelling of the title: “Ruddygore” • Whatever opera followed The Mikado was likely to suffer by comparison Ruddigore Time: Early 19th Century Place: Cornwall, England Act 1: The village of Rederring Act 2: The picture gallery of Ruddigore Castle, one week later Ruddigore Dramatis Personae Mortals: •Sir Ruthven Murgatroyd, Baronet, disguised as Robin Oakapple (Patter Baritone) •Richard Dauntless, his foster brother, a sailor (Tenor) •Sir Despard Murgatroyd, Sir Ruthven’s younger brother -

The House of Coburg and Queen Victoria: a Study of Duty and Affection

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 6-1-1971 The House of Coburg and Queen Victoria: A study of duty and affection Terrence Shellard University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Recommended Citation Shellard, Terrence, "The House of Coburg and Queen Victoria: A study of duty and affection" (1971). Student Work. 413. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/413 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HOUSE OF COBURG AND QUEEN VICTORIA A STORY OF DUTY AND AFFECTION A Thesis Presented to the Department of History and the Faculty of the Graduate College University of Nebraska at Omaha In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Terrance She Ha r d June Ip71 UMI Number: EP73051 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Diss««4afor. R_bJ .stung UMI EP73051 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest LLC. -

Major Alfred Rent Heneage, Highlander and Dragoon

Major Alfred Rent Heneage, May 23, 1888. Heneage appears to have been a strong Highlander and Dragoon horseman as he won the 5th Dragoon Guards Challenge Cup in 1893 riding his own horse, Sea King. Barney Mattingly Heneage served with the 5th Dragoon Guards while they were stationed in the United Kingdom but was assigned Alfred Ren4 Heneage was born on June 10, 1858 in Stags to the depot at Canterbury when the 5th Dragoon Guards End, Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire, England, the third were posted to India on September 6, 1893 and remained son of Edward Fieschi Heneage (1802-1880), Member with the depot until September 1897. After this, Heneage of Parliament for Grimsby, and his second wife, Renee traveled to India to rejoin the regiment, being promoted Elisabeth Levina Hoare (1825-1871). Educated at Major on January 22, 1898. At this time, the regiment Cheltenham College, Heneage was commissioned a Sub was commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel R. S. Baden- Lieutenant in the 74th Highlanders on September 11, Powell (Figure 2), who would go on to fame for leading 1876 and promoted Lieutenant on September 11, 1877. the defense of Mafeking (October 1899 to May 1900) The regiment was associated with the 71st Highland and for founding the Boy Scouts in 1908. Light Infantry on July 1, 1881 and re-designated the 2nd Battalion Highland Light Infantry (City of Glasgow Heneage served with the 5th Dragoon Guards during the Regiment). Boer War. The regiment was stationed in India and was among the first units ordered to South Africa. Heneage Upon the outbreak of hostilities in 1882, the 2nd arrived at Ladysmith on October 26, 1899 as commander Battalion, Highland Light Infantry was ordered to of B Squadron, just prior to the beginning of the siege. -

The West Coast Directory for 1883-84

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/westcoastdirecto18834dire i " m A PLATE GLAS INSURANCES AND EEPLACEMENTS PROMPT "ECTED at moderate rates CALEDONIAN PLAT 1SS IH'StJRAKOE CO (ESTABLISHED 1871 UNDE;*. OMPAN1ES' ACT, 1S62-1867.) Head fee—131 HOPE STR GLASGOW, and AGENTS, W. I IN.M'CULLQCH, Manager. FIRE & LIFE INS NOE COMPANY. I estab: 1714. Fira Funis, £720,093. Lif j Faai WW*. Total FuaIs,£l,80O,00!>. FIRE RISKS accept] r LOWEST RATES. LARGE BONUSES LIFE POLICIES. Scottish Office—W HOPE i T, GLASGOW, and Agents. W. M'GAVI-K ITLLOCH, Local Manager. AGENT LIFE AS 3 U RAN ASSOCIA r ION. Established 1839 I CAPITAL, ONE MILLION 120 PRINCES S~ ET EDINBURGH. TR BM. The Right Hon. The Earl of Gl- Lord Clerk-Register of Scotland. The Right Hun. Lord Moncreifi • Justice-Clerk of Scotland. Tne Honourable Lord Adam. Edward Kent Karslake, Esq., Q.C. The Honourable Mr Justice Field. William Smythe, Esq , of Methven. Sir Hardinge S' - Giffard. Q.C, M.P. Ma nage r— W I LL I ITH, LL.D., F.I.A. THE ASSOCIATION transacts all the .ascriptions of LIFE and ANNUITY Bnsi- ness, and also secures ENDOWMEi ayable during Life, as PROVISIONS FOR OLD AGE. NINE-TENTHS (90 percent.) of the PR are divided among the Assured every FIVE YEARS. Seven Divisions of Profits h; sady taken place, at each of which BONUS AUDITIONS, at Rates never lower than t iund Ten Shillings per Cent per Annum, were made to all Participating Policies ( I for the Whole Term of Life. -

Surgeon-General Sir William Taylor, K.C.B., Late Director-General, Army Medical Service, Which Took Place at Windsor on the 10Th April

Surgeon-General Sir WILLIAM TAYLOK, K.C.B., M.D.Glasg., Late Director-General Army Medical Service. We regret to announce the death of Surgeon-General Sir William Taylor, K.C.B., late Director-General, Army Medical Service, which took place at Windsor on the 10th April. Sir William Taylor was the third son of the late James Taylor of Etruria, Staffordshire, and of Moorfield, Ayrshire, where he was born in 1843. He received his early education at Carmichael, in the Upper Ward of Lanarkshire, whence he went to the University of Glasgow for the study of medicine, receiving its degrees of M.D. and C.M. in 1864. In the same year he obtained a commission as assistant surgeon in the Army Medical De- partment, and from 1865 to 1869 he served in Canada, where he took part in the operations against the Fenian raiders, and received the medal. In 1870, after his return to England, he Obituary. 293 was gazetted to the Royal Artillery, and three years later he went to India, where in 1877 he took part in the Jowaki Afridi expedition, for which he received the medal. He left India in 1880 for a brief period of service in England, but returned in 1882, and in 1885 was appointed surgeon to Sir Frederick Roberts, then Commander-in-Chief in India. He served through the Burma campaign of 1885-86 on the staff of the Commander- in-Chief, and was mentioned in dispatches. In 1888 he served with the Hazara Expedition, and in 1888-89 he again served in the Burmese campaign.