Young People & Brexit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ECON Thesaurus on Brexit

STUDY Requested by the ECON Committee ECON Thesaurus on Brexit Fourth edition Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies Authors: Stephanie Honnefelder, Doris Kolassa, Sophia Gernert, Roberto Silvestri Directorate General for Internal Policies of the Union July 2017 EN DIRECTORATE GENERAL FOR INTERNAL POLICIES POLICY DEPARTMENT A: ECONOMIC AND SCIENTIFIC POLICY ECON Thesaurus on Brexit Fourth edition Abstract This thesaurus is a collection of ECON related articles, papers and studies on the possible withdrawal of the UK from the EU. Recent literature from various sources is categorised, chronologically listed – while keeping the content of previous editions - and briefly summarised. To facilitate the use of this tool and to allow an easy access, certain documents may appear in more than one category. The thesaurus is non-exhaustive and may be updated. This document was provided by Policy Department A at the request of the ECON Committee. IP/A/ECON/2017-15 July 2017 PE 607.326 EN This document was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs. AUTHORS Stephanie HONNEFELDER Doris KOLASSA Sophia GERNERT, trainee Roberto SILVESTRI, trainee RESPONSIBLE ADMINISTRATOR Stephanie HONNEFELDER Policy Department A: Economic and Scientific Policy European Parliament B-1047 Brussels E-mail: [email protected] LINGUISTIC VERSIONS Original: EN ABOUT THE EDITOR Policy departments provide in-house and external expertise to support EP committees and other parliamentary bodies -

“We Wanted a Parliament but They Gave Us a Stone” the Coronation Stone of the Scots As a Memory Box in the Twentieth Century

“We wanted a parliament but they gave us a stone” The Coronation Stone of the Scots as a Memory Box in the Twentieth Century JÖRG ROGGE In this article a memory box is presented, in which and to which different meanings were contained and attached in the course of seven centuries.1 This memory box is the coronation stone of Scottish kings, nowadays on display in Edinburgh Castle, the external form of which has remained for the most part unchanged. The roughly 150 kg heavy, 67 cm long, 42 cm wide and 28 cm high sandstone block was used in the Middle Ages at the inauguration of Scottish kings.2 In the course of history, however, it was removed from its original functional context and transferred to other cultural and political contexts. In this connection, both diachronic and also synchronic transfers of the coronation stone and the concepts of political order in the island of Britain stored in it were carried out. At present it is still an important memory box filled with political concepts, and it was and is a starting point for research into the relationship between the Scots and the English over the past 700 years. It is remarkable that this stone was used by nationally emotional Scots and also by the Government in London as symbol in important debates in the twentieth century. Historical recollections are transported by the Scots and the English with the stone that one may certainly call a container of memory. Here I 1 My thanks go to John Deasy for translating the German text into English as well as to the editors for finishing the final formatting. -

Brexit: Initial Reflections

Brexit: initial reflections ANAND MENON AND JOHN-PAUL SALTER* At around four-thirty on the morning of 24 June 2016, the media began to announce that the British people had voted to leave the European Union. As the final results came in, it emerged that the pro-Brexit campaign had garnered 51.9 per cent of the votes cast and prevailed by a margin of 1,269,501 votes. For the first time in its history, a member state had voted to quit the EU. The outcome of the referendum reflected the confluence of several long- term and more contingent factors. In part, it represented the culmination of a longstanding tension in British politics between, on the one hand, London’s relative effectiveness in shaping European integration to match its own prefer- ences and, on the other, political diffidence when it came to trumpeting such success. This paradox, in turn, resulted from longstanding intraparty divisions over Britain’s relationship with the EU, which have hamstrung such attempts as there have been to make a positive case for British EU membership. The media found it more worthwhile to pour a stream of anti-EU invective into the resulting vacuum rather than critically engage with the issue, let alone highlight the benefits of membership. Consequently, public opinion remained lukewarm at best, treated to a diet of more or less combative and Eurosceptic political rhetoric, much of which disguised a far different reality. The result was also a consequence of the referendum campaign itself. The strategy pursued by Prime Minister David Cameron—of adopting a critical stance towards the EU, promising a referendum, and ultimately campaigning for continued membership—failed. -

Alastair Campbell

Alastair Campbell Adviser, People’s Vote campaign 2017 – 2019 Downing Street Director of Communications 2000 – 2003 Number 10 Press Secretary 1997– 2000 5 March 2021 This interview may contain some language that readers may find offensive. New Labour and the European Union UK in a Changing Europe (UKICE): Going back to New Labour, when did immigration first start to impinge in your mind as a potential problem when it came to public opinion? Alastair Campbell (AC): I think it has always been an issue. At the first election in 1997, we actually did do stuff on immigration. But I can remember Margaret McDonagh, who was a pretty big fish in the Labour Party then, raising it often. She is one of those people who does not just do politics in theory, in an office, but who lives policy. She is out on the ground every weekend, she is knocking on doors, she is talking to people. I remember her taking me aside once and saying, ‘Listen, this immigration thing is getting bigger and bigger. It is a real problem’. That would have been somewhere between election one (1997) and election two (2001), I would say. Politics and government are often about very difficult competing pressures. So, on the one hand, we were trying to show business that we were serious about business and that we could be trusted on the economy. One of the messages that business was giving us the whole time was that Page 1/31 there were labour shortages, skill shortages, and we were going to need more immigrants to come in and do the job. -

Page 1 Donald Tusk President of the European Council Europa Building

Donald Tusk President of the European Council Europa Building Rue de la Loi/Wetstraat 175 B-1048 Bruxelles/Brussel Belgium 24 November 2018 Subject: The Draft Agreement of 14 November 2018 on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union Dear Mr Tusk On Saturday 20 October, 700,000 people from all parts of the UK marched in London to demonstrate their opposition to Brexit and their wish to remain at the heart of Europe. The people who came spanned the generations, from babies riding on their mothers’ shoulders to old people who struggled bravely to walk the route of the march. We write as a grassroots network linking many of the pro-European campaign groups which have sprung up all over the United Kingdom and beyond, and whose supporters were on that march. Our movement is growing rapidly, as more and more people living in the UK come to realise what Brexit means for us as individuals, for our country and for Europe as a whole. Arguably, the UK now has the largest and most passionate pro-EU supporter base in the whole of Europe! We wish to make you aware of the strength of feeling on this matter amongst the people of the United Kingdom. Millions of us want to retain the rights and freedoms granted to us under the EU Treaties and to continue to play a role at the heart of Europe. Brexit in any form would take away rights which we all hold as individuals, but we do not accept that these rights can be taken away without our consent. -

Environmental Education – the Path to Sustainable Development Contents

Environmental Education – the path to Sustainable Development Contents Promoting a sense of responsibility through environmental education Page 05 The United Nations has designated the period 2005 to 2014 as the decade of “Education for Sustainable Development”. The objective is to integrate the concept of sustainable develop- ment in education processes around the world. Environmental education is an integral aspect of this concept. It is a process of action-orient- ed, political learning. The European Green Dot programme is making a significant con- tribution to making people promote sustain- able development. Green Dot – promoting environmental awareness and motivating people Page 12 The Green Dot and partner organisations have contributed in creating routine attitudes, values and actions, and establishing a Euro- pean platform for environmental awareness. They promote active citizenship through diverse local, regional and national education pro- grammes for the entire education chain. Many of the activities are realised in partnership programmes with manufacturing and retail enterprises, authorities and recycling companies. 02 03 Environmental education as a means of promoting European integration Page 22 No other political objective is more dependent on successful cooperation than sustainability. The Green Dot environmental education pro- gramme’s internationally networked projects are therefore focused towards European in- tegration. Young people in various countries learn to share responsibilities as well as prac- tise democracy by working on solutions to- gether as a group. Two prominent examples are the 1st European Youth Eco-Parliament and the Baltic Sea Project. Sustainability needs networked thinking and action Page 29 Global environmental issues, such as the greenhouse effect, the decimation of bio- logical diversity and the consumption of finite resources can only be solved on the basis of more intensive international cooper- ation. -

Global Free Trade

Library Note Leaving the European Union: Global Free Trade On 27 October 2016, the House of Lords will debate the following motion, tabled by Lord Leigh of Hurley (Conservative): That this House takes note of the opportunities presented by the United Kingdom’s departure from the European Union for this country to be an outward looking champion of global free trade, and the potential benefits this will bring both domestically and internationally. During her speech to the Conservative Party Conference on 5 October 2016, the Prime Minister, Theresa May, stated that part of the UK’s role upon the world stage after leaving the EU would be to act as an advocate for global free trade rights. The Secretary of State for International Trade, Liam Fox, has also suggested that the UK’s departure from the EU will provide an opportunity for the UK to become a world leader in free trade. The Government has said that it has begun preliminary explorative talks with some countries outside the EU on potential new trade deals once the UK has left the EU. The UK’s future trading relationship with the EU is to be the subject of negotiations for the UK’s departure. The Parliamentary Under Secretary of State at the Department for Exiting the European Union, Lord Bridges of Headley, has stated that the Government is looking to achieve “the freest possible” trading relationship with EU member states. The UK Government has also said that it wants to have greater control over its immigration policy outside the EU. The President of the European Council, Donald Tusk, has stated the EU would not compromise on rules for the free movement of people and allow the UK to retain its current level of access to the European single market. -

Food and Health in Europe: Europe: in Health and Food WHO Regional Publications

Food and health in Europe: Food and health WHO Regional Publications European Series, No. 96 a new basis for action Food and health in Europe: a new basis for action 96 The World Health Organization was established in 1948 as a specialized agency of the United Nations serving as the directing and coordinating authority for international health matters and public health. One of WHO’s constitutional functions is to provide objective and reliable information and advice in the field of human health, a responsibility that it fulfils in part through its publications programmes. Through its publications, the Organization seeks to support national health strategies and address the most pressing public health concerns. The WHO Regional Office for Europe is one of six regional offices throughout the world, each with its own programme geared to the particular health problems of the countries it serves. The European Region embraces some 870 million people living in an area stretching from Greenland in the north and the Mediterranean in the south to the Pacific shores of the Russian Federation. The European programme of WHO therefore concentrates both on the problems associated with industrial and post-industrial society and on those faced by the emerging democracies of central and eastern Europe and the former USSR. To ensure the widest possible availability of authoritative information and guidance on health matters, WHO secures broad international distribution of its publications and encourages their translation and adaptation. By helping to promote and protect health and prevent and control disease, WHO’s books contribute to achieving the Organization’s principal objective – the attainment by all people of the highest possible level of health. -

Elitist Britain? Foreword

Elitist Britain? Foreword This report from the Commission on Social Mobility and Child This risks narrowing the conduct of public life to a small few, Poverty Commission examines who is in charge of our who are very familiar with each other but far less familiar with country. It does so on the basis of new research which has the day-to-day challenges facing ordinary people in the analysed the background of 4,000 leaders in politics, country. That is not a recipe for a healthy democratic society. business, the media and other aspects of public life in the UK. To confront the challenges and seize the opportunities that This research highlights a dramatic over-representation of Britain faces, a broader range of experiences and talents need those educated at independent schools and Oxbridge across to be harnessed. Few people believe that the sum total of the institutions that have such a profound influence on what talent in Britain resides in just seven per cent of pupils in our happens in our country. It suggests that Britain is deeply country’s schools and less than two per cent of students in our elitist. universities. The risk, however, is that the more a few That matters for a number of reasons. In a democratic society, dominate our country’s leading institutions the less likely it is institutions – from the law to the media – derive their authority that the many believe they can make a valuable contribution. in part from how inclusive and grounded they are. Locking out A closed shop at the top can all too easily give rise to a “not a diversity of talents and experiences makes Britain’s leading for the likes of me” syndrome in the rest of society. -

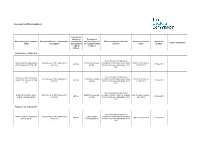

Information on Cases

Casework and Investigations Decision on offence or Decision on Name and type of regulated Potential offence or contravention contravention sanction (imposed Brief summary of reason for Outcome or current Status last Further information entity investigated (by regulated on regulated entity decision status updated entity or or officer) officer) Published on 21 May 2019 The Commission considered, in Liberal Democrats (Kensington Late delivery of 2017 statement of £200 (fixed monetary accordance with the enforcement policy, Paid on initial notice on Offence 21 May 2019 and Chelsea accounting unit) accounts penalty) that sanctions were appropriate in this 25 April 2019 case. The Commission considered, in Liberal Democrats (Camborne, Late delivery of 2017 statement of £200 (fixed monetary accordance with the enforcement policy, Paid on initial notice on Redruth and Hayle accounting Offence 21 May 2019 accounts penalty) that sanctions were appropriate in this 25 April 2019 unit) case. The Commission considered, in Scottish Democratic Alliance Late delivery of 2017 statement of £200 (fixed monetary accordance with the enforcement policy, Due for payment by 12 Offence 21 May 2019 (registered political party) accounts penalty) that sanctions were appropriate in this June 2019 case. Published on 16 April 2019 The Commission considered, in British Resistance (registered Late delivery of 2017 statement of £300 (variable accordance with the enforcement policy, Offence Paid on 23 April 2019 21 May 2019 political party) accounts monetary penalty) that sanctions were appropriate in this case. The Commission considered, in Due for payment by 3 The Entertainment Party Late delivery of 2017 statement of £200 (fixed monetary accordance with the enforcement policy, May 2019. -

Casualty Actuarial Society E-Forum, Spring 2009

Casualty Actuarial Society E-Forum, Spring 2009 Including the 2009 CAS Reinsurance Call Papers The 2009 CAS Reinsurance Call Papers Presented at the 2009 Reinsurance Seminar May 18-19, 2009 Hamilton, Bermuda The Spring 2009 Edition of the CAS E-Forum is a cooperative effort between the Committee for the CAS E-Forum and the Committee on Reinsurance Research. The CAS Committee on Reinsurance Research presents for discussion four papers prepared in response to their 2009 Call for Papers. This E-Forum includes papers that will be discussed by the authors at the 2009 Reinsurance Seminar May 18-19, 2009, in Hamilton, Bermuda. 2009 Committee on Reinsurance Research Gary Blumsohn, Chairperson Avraham Adler Guo Harrison Michael L. Laufer Nebojsa Bojer David L. Homer Yves Provencher Jeffrey L. Dollinger Ali Ishaq Manalur S. Sandilya Robert A. Giambo Amanda Kisala Michael C. Tranfaglia Leigh Joseph Halliwell Richard Scott Krivo Joel A. Vaag Robert L. Harnatkiewicz Alex Krutov Paul A. Vendetti Casualty Actuarial Society E-Forum, Spring 2009 ii 2009 Spring E-Forum Table of Contents 2009 Reinsurance Call Papers Unstable Loss Development Factors Gary Blumsohn, FCAS, Ph.D., and Michael Laufer, FCAS, MAAA................................................... 1-38 An Analysis of the Market Price of Cat Bonds Neil M. Bodoff, FCAS, MAAA, and Yunbo Gan, Ph.D....................................................................... 1-26 Common Pitfalls and Practical Considerations in Risk Transfer Analysis Derek Freihaut, FCAS, MAAA, and Paul Vendetti, FCAS, MAAA.................................................... 1-23 An Update to D’Arcy’s “A Strategy for Property-Liability Insurers in Inflationary Times” Richard Krivo, FCAS .................................................................................................................................. 1-16 Additional Papers Paid Incurred Modeling Leigh J. -

Medieval Theories of Natural Law: William of Ockham and the Significance of the Voluntarist Tradition Francis Oakley

Notre Dame Law School NDLScholarship Natural Law Forum 1-1-1961 Medieval Theories of Natural Law: William of Ockham and the Significance of the Voluntarist Tradition Francis Oakley Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/nd_naturallaw_forum Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Oakley, Francis, "Medieval Theories of Natural Law: William of Ockham and the Significance of the Voluntarist Tradition" (1961). Natural Law Forum. Paper 60. http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/nd_naturallaw_forum/60 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Natural Law Forum by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MEDIEVAL THEORIES OF NATURAL LAW: WILLIAM OF OCKHAM AND THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE VOLUNTARIST TRADITION Francis Oakley THE BELIEF in a natural law superior to mere positive enactment and the practice of appealing to it were common to the vast majority of medieval political thinkers'-whether civil lawyers or philosophers, canon lawyers or theologians; and, all too often, it has been assumed that when they invoked the natural law, they meant much the same thing by it. It takes, indeed, little more than a superficial glance to discover that the civil or canon lawyers often meant by natural law something rather different than did the philoso- phers or theologians, but it takes perhaps a closer look to detect that not even the theologians themselves were in full agreement in their theories of natural