Pdf Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Changes in Rye Bay

CHANGES IN RYE BAY A REPORT OF THE INTERREG II PROJECT TWO BAYS, ONE ENVIRONMENT a shared biodiversity with a common focus THIS PROJECT IS BEING PART-FINANCED BY THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY European Regional Development Fund Dr. Barry Yates Patrick Triplet 2 Watch Cottages SMACOPI Winchelsea DECEMBER 2000 1,place de l’Amiral Courbet East Sussex 80100 Abbeville TN36 4LU Picarde e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] Changes in Rye Bay Contents Introduction 2 Location 3 Geography 4 Changes in Sea Level 5 A Timeline of Rye Bay 270 million - 1 million years before present (BP ) 6 450,000-25,000 years BP 6 25,000 – 10,000 years BP 6 10,000 – 5,000 years BP 6 5,000 - 2,000 years BP 7 1st – 5th Century 8 6th – 10th Century 8 11th Century 8 12th Century 8 13th Century 9 14th Century 11 15th Century 12 16th Century 12 17th Century 13 18th Century 15 19th Century 16 20th Century 18 The Future Government Policy 25 Climate Change 26 The Element Of Chance 27 Rye Bay Bibliography 28 Rye Bay Maps 32 2 Introduction This is a report of the Two Bays, One Environment project which encompasses areas in England and France, adjacent to, but separated by the English Channel or La Manche. The Baie de Somme (50 o09'N 1 o27'E) in Picardy, France, lies 90 km to the south east of Rye Bay (50 o56'N 0 o45'E) in East Sussex, England. Previous reports of this project are …… A Preliminary Comparison of the Species of Rye Bay and the Baie de Somme. -

Strategic Flood Risk Assessment Level 1

STRATEGIC FLOOD RISK ASSESSMENT – LEVEL 1 August 2008 ROTHER DISTRICT COUNCIL Contents: Page No. 1. Introduction, including Geology, Climate Change, SUDS, Sequential 5 Test, Exception Test and Emergency Planning 23 2. Methodology, including Approach 3. Flood Risk Assessment (attached) 30 3.1 Tidal Flooding 32 3.2 Fluvial Flooding 36 3.3 Surface Water Drainage Flooding 44 3.4 Highway Flooding 45 3.5 Sewerage Flooding 46 3.6 Reservoirs 47 4. Recommendation for SFRA Level 2 and Interim draft Policy guidance 48 for development in different flood zones Appendices: 1. Map showing Rother District, with Flood Zone 2 (2007) 51 2. Plans showing areas of development that are affected by flood risk 52 areas 3 Map showing SMP – Policy Unit Areas 53 4. Map showing Problem Drainage Areas in Rother District () 54 5. Key Maps showing:- EA Flood Zone 2 (2007 55 EA Flood Zone 3 (2007) EA Flood Map Historic (2006)s EA Flood Defences Benefit Areas (2007) EA Flood Defences (2007) EA Banktop E Planning EA Main Rivers Map SW Sewer Inverts SW Sewer Lines SW Sewer Points 6. Sewerage Flooding Incidents (Southern Water) over past 10 years 56 (Schedule attached) 7. Local Plan Policies that will need to be reconsidered in light of the 57 SFRA 8. Schedule of the locations most prone to Highway Flooding in Rother 59 District 2 9. Emergency Planning Officers Plan 63 10. Plan showing locations most prone to Highway Flooding in Rother 76 District 11. Location of sewerage flooding incidents (Southern Water) over past 77 10 years (Map) 12. The Sequential Test 78 3 References: 1. -

East Sussex Fire Authority Our Corporate Plan 2019-2020 Alternative Formats and Translation Contents Introduction

We make our communities safer East Sussex Fire Authority Our Corporate Plan 2019-2020 Alternative formats and translation Contents Introduction...........................................................................................................................2 The Fire Authority...................................................................................................................4 The Members of the Fire Authority are:.................................................................................5 About East Sussex Fire and Rescue Service........................................................................6 Service Structure...................................................................................................................8 Setting the strategic direction.................................................................................................9 Our Strategies.....................................................................................................................10 Our priorities........................................................................................................................10 Delivering our purpose and commitments...........................................................................11 What we’ve achieved and our plans for this year................................................................12 Celebrating staff success.....................................................................................................26 Asking the public..................................................................................................................28 -

NRA Southern 9

NRA Southern 9 NRA National Rivers Authority Southern Region June 1994 E n v ir o n m e n t A g e n c y NATIONAL LIBRARY & INFORMATION SERVICE HEAD OFFICE Rio House, Waterside Drive, Aztec West, Almondsbury, Bristol BS32 4UD ENVIRONMENT AGENCY 099845 O National Rivers Authority 1994. First published June 1994. All reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or otherwise transmitted, i photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior p 'thority For further information, pi Public Relations Dep National Rivers Aut Guildbourne Ho h O; ilC0 Chatsworth Ro Worthing West Sussex CtO ii : , D _____ BN U 1LD Designed by GSBA and printed on Seque The NRA is committted to the principles o f stewardship and $«>.— ------------■« ; . Accession No f t f c C . P / . responsibilities as Guardians o f the Water Environment, the NRA will aim to establish and demt 3 environmental practice throughout all its functions. INTRODUCTION The NRA has specific responsibilities relating to Navigation together with those for Recreation, Conservation, Fisheries, Water Quality, Flood Defence and Water Resources. The aim of the N RA in respect of Navigation is to improve and maintain controlled waters and their facilities for use by the public where the NRA is the navigation authority. It is this aim which underpins the N R A ’s management of the Fiarbour of Rye. The Fiarbour of Rye Management Plan sets out the NRA’s future plans for the management of the Harbour, pursuing a policy of integrated management through balancing the needs of all the Harbour users. The Plan covers the period 1994/95 to 1997/98 and the area it covers is shown on the map. -

Poplin Marsh, Eastbourne Romano-British Ceramic Building Material (CBM) – Site Number 1992.1 (Unpublished)

CERAMIC BUILDING MATERIAL AND POTTERY REPORT ELFWICK FIELD SMALLHYTHE PLACE SMALLHYTHE ROAD TENTERDEN KENT TN30 7NG National Grid Reference Centred on: TQ 8927 3001 Report by Kevin and Lynn Cornwell Joint Field Officers Hastings Area Archaeological Research Group Registered Charity No. 294989 May 2020 1 Cover Photograph – A selection of Romano-British ceramic building material from Elfwick Field, Smallhythe Place, Smallhythe, Tenterden, Kent – photograph by Kevin Cornwell. Introduction Members of Hastings Area Archaeological Research Group conducted geophysical surveys at Smallhythe Place, Smallhythe Road, Tenterden, Kent between July 2019 – January 2020 (Cornwell & Cornwell 2020). During the field work artefacts were identified at two locations in Elfwick Field (site ‘A’ centred on NGR TQ 89274 30019 & site ‘B’ TQ 89250 29909). Nathalie Cohen, National Trust Archaeologist for London and the South East was alerted and the authors of this report were invited to comment on the archive. The Romano-British Ceramic Building Material (CBM) has been compared with previous analyses undertaken by Hastings Area Archaeological Research Group on archives from Castle Croft, Ninfield (Cornwell et al Summer 2007), Kitchenham Farm, Ashburnham (Cornwell et al Winter 2007; Cornwell & Cornwell Summer 2008), Chitcombe Farm, Brede (report forthcoming), Eight Acre Field, Crockers, Northiam (report forthcoming), Fagg Farm, Udimore (Cornwell & Cornwell 2016), Poplin Marsh, Eastbourne (Cornwell 2016) and Old House Farm, Ringmer (Cornwell 2018). The material has been divided into identifiable categories which include tegulae, imbrices, box-flue, flat tile/brick groups, here referred to as flat tiles. These have been sub-divided and the details commented on. A percentage of the material is abraded and cannot to be categorized as is common on many sites. -

Rock Channel, Rye, East Sussex on Behalf of Martello Developments

HERITAGE STATEMENT in connection with ROCK CHANNEL RYE EAST SUSSEX on behalf of Martello Developments Ref: DGC21910 Date of Issue: 8th March 2019 Web: www.dgc-onsultants.com Heritage and Significance Statement: Rock Channel, Rye, East Sussex On behalf of Martello Developments Table of Contents 1.0 Overview and Summary ...................................................................................3 2.0 Heritage Policy and Guidance Summary .......................................................3 3.0 Methodology ......................................................................................................9 4.0 Statement of Significance ............................................................................. 10 5.0 Historic Overview ........................................................................................... 11 6.0 Significance Assessment .............................................................................. 22 7.0 Proposals ........................................................................................................ 40 8.0 Impact .............................................................................................................. 42 9.0 Conclusion ...................................................................................................... 44 All Rights reserved. Copyright © DGC (Historic Buildings Consultants Limited While Copyright in this volume document report as a whole is vested in DGC (Historic Buildings) Consultants LTD, copyright to individual contributions regarding -

SFRA Level 1 Appendix

APPENDIX 6 Sewerage Flooding Incidents (Southern Water) over the past 10 years 56 APPENDIX 7 Local Plan Policies that will need to be reconsidered in the light of the SFRA 57 Appendix 7 Local Plan Policies that will need to be re-considered in the light of the SFRA DS1 (v) Infrastructure (vi) Undeveloped coastline (xi) Development safe from flooding (xiii) Avoiding unstable land GD1 (ix) Infrastructure (x) Drainage and Water Quality (xv) Flood Risk – minimise and manage GD2 Infrastructure EM5 Industry/storage (DB Earthmoving) – not in flood risk area EM7 New or extended tourist attractions/facilities EM8 Bodiam/Robertsbridge railway – not compromise flood plain EM9 Tourist accommodation – in accordance with other policies (development boundaries) EM10 Caravans/Chalets/Tents – not in high risk flood area EM11 Occupancy of Caravans/Chalets/Tents – Seasonal flood risk RY3 Rock Channel (subject of current SPD) RY4 Thomas Peacocke Lower School RY5 Land north of Udimore Road (small part) RY6 Rye Town Centre (Dry Island) RY7 Harbour Road Employment Area RY8 Adjacent Stonework Cottages, Rye Harbour DS3 Development Boundaries • The development boundaries of Norman’s Bay, Pett Level, Winchelsea Beach, Rye Harbour and Camber are wholly or almost wholly within a Flood Risk Area • The Citadel or historic core areas of both Rye and Winchelsea are “Dry Islands”, with surrounding development in a Flood Risk area (and access to the ‘Dry Island’) • Parts of Bexhill, Crowhurst, Etchingham, Bodiam, Robertsbridge, Three Oaks and Sedlescombe, that are within the development boundary are also within a Flood Risk Area. • Parts of Fairlight Cove that are within the development boundary are also susceptible to cliff erosion and landslip • Parts of Battle, Rye and Stonegate that are within the development boundary are also within a Groundwater Source Protection Zone 58 APPENDIX 8 Schedule of the locations most prone to Highway Flooding in Rother 59 Appendix 8 HIGHWAY FLOODING (i) Highway Flooding Hotspots in Rother District (ESCC) 1. -

Environment Agency Rip House, Waterside Drive Aztec West Almondsbury Bristol, BS32 4UD

En v ir o n m e n t Agency ANNEX TO 'ACHIEVING THE QUALITY ’ Programme of Environmental Obligations Agreed by the Secretary of State for the Environment, Transport and the Regions and for Wales for Individual Water Companies As financed by the Periodic Review of Water Company Price Limits 2000*2005 The Environment Agency Rip House, Waterside Drive Aztec West Almondsbury Bristol, BS32 4UD June 2000 ENVl RO N ME NT, AGEN CY 1 ]2 7 0 0 CONTENTS For each water and sewerage company' there are separate lists for continuous, intermittent discharges and water abstraction sites. 1. Anglian Water 2. Welsh Water 3. Northumbrian Water Group Pic 4. North West Water Pic 5. Severn Trent Pic 6. Southern Water Pic 7. South West Water Pic 8. Thames Water Pic 9. Wessex Water Pic 10. Yorkshire Water Pic 11. List of water abstraction sites for water supply only companies National Environment Programme Key E A R e g io n Water Company ID Effluent Type A A n g lia n . A Anglian Water SCE Sewage Crude Effluent M Midlands DC Dwr Cymru Welsh Water SSO Sewage Storm Overflows NE North East N Northumbrian Water STE Sewage Treated Effluent NW North W est NW North West Water CSO Combined Sewer Overflow S Southern ST Severn Trent Water EO Emergency Overflow SW South W est S Southern Water ST Storm Ta n k T Th a m e s sw South West Water . WA W ales T Thames Water Receiving Water Type wx Wessex Water C Coastal Y Yorkshire Water E Estuary G Groundwater D rive rs 1 Inland CM 3 CM 1 Urban Waste Water Treament Directive FF1 - 8 Freshwater Fisheries Directive Consent conditions/proposed requirements **!**!** GW Groundwater Directive Suspended solids/BOD/Ammonia SW 1 -12 Shellfish Water Directive NR Nutrient Removal S W A D 1 - 7 Surface Water Abstraction Directive P Phosphorus (mg/l) H A B 1 - 6 Habitats Directive N Nitrate (mg/i) B A T H 1 -1 3 Bathing Water Directive 2 y Secondary Treatment SSSI SSSI 3 y Tertiary Treatment QO(a) - QO(g) River and Estuarine Quality Objectives LOC Local priority schemes . -

Playden Walk 3 Miles/5 Kms

Walk Walk Walk Location Map Essential Information Distance: Playden Walk 3 miles/5 kms Walk grade: A generally easy walk, with few 2 stiles, but some hilly sections and a flight of steps. Maps: OS Explorer 125 OS Landranger 189 Start/Finish: Rye Railway Station TQ 919205 Public Transport: Buses: A regular bus service operates Monday to Saturday between Hastings and Northiam via Rye, with a stop in Playden. Trains: Rye Station is on the Hastings to Ashford line and has a regular service. Parking: Parking is available in Rye. Location Symbols Bus stop/Request stop Railway Station Walk Location Route 41 Paths to Prosperity Refreshments and We hope that you enjoy the walk in this East Sussex is a welcome haven for walkers leaflet, which is one of a series produced in the busy south-east of England, with over Local Services by East Sussex County Council. (see map for location) two thirds of the County covered by the Copies of the leaflets for other walks in High Weald and Sussex Downs Areas of the series are available from Tourist Outstanding Natural Beauty. Information Centres and libraries or 1 Wisteria Corner direct from East Sussex County Council, There is also a wealth of picturesque villages, Bed & Breakfast and Self Catering by contacting the Rights of Way Team:- country houses and parkland hidden within Accommodation - 01797 225011 its rolling landscape, waiting to be By phone on:- 2 Apothecary House 01273 482250 / 482354 / 482324 discovered. Bed & Breakfast Accommodation - 01797 229157 By post at:- Please come and enjoy the unique splendours Transport and Environment Department of our countryside, but please also support 3 Landgate Bistro County Hall the local businesses that help make the Restaurant - 01797 222829 St. -

10. Medieval Farming and Flooding in the Brede Valley

Romney Marsh: the Debatable Ground (ed. J. Eddison), OUCA Monograph 41, 1995 10. Medieval Farming and Flooding in the Brede Valley Mark Gardiner The eastern part of the High Weald is drained by a eastwards in a valley which increases in width below the number of rivers - the Rother, Tillingham, Brede and confluence with Forge Stream and is crossed by a bridge Pannel - which flow outwards to Walland Marsh. The to the south of the village of Brede. From there the river history of the development of the marsh and the river occupies a broad valley little or no higher than the adjoining valleys are closely associated, for the drainage of one has marshlands. At its eastern end it runs though the marshes had a profound influence on the other. An analysis of the between Winchelsea and Rye. As the river leaves the lithostratigraphy of these valleys has been undertaken valley it turns towards the south to run at the foot of New (Waller et al. 1988), but very little attention has been Winchelsea hill before following a northward course to given to the more recent history, and particularly to the join the Rother near Rye (Fig. 10.1). impact of human activity in these areas. With the exception Throughout the medieval period the lower part of the of the work by Eddison on the Rother valley, the Brede valley was liable to flooding, both from the water development of drainage in the valleys leading into the of the river itself and from sea water entering the estuary. marsh has been almost entirely neglected (Eddison 1985; The valley from Lidham Brook eastwards seems to have 1988; 1995). -

4 the Rights of Way Network in East Sussex

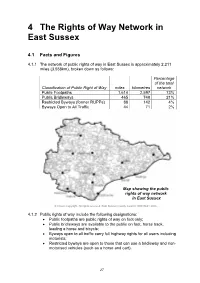

4 The Rights of Way Network in East Sussex 4.1 Facts and Figures 4.1.1 The network of public rights of way in East Sussex is approximately 2,211 miles (3,558km), broken down as follows: Percentage of the total Classification of Public Right of Way miles kilometres network Public Footpaths 1,614 2,597 73% Public Bridleways 465 748 21% Restricted Byways (former RUPPs) 88 142 4% Byways Open to All Traffic 44 71 2% Map showing the public rights of way network in East Sussex © Crown Copyright. All rights reserved. East Sussex County Council 100019601.2006 4.1.2 Public rights of way include the following designations: • Public footpaths are public rights of way on foot only; • Public bridleways are available to the public on foot, horse back, leading a horse and bicycle; • Byways open to all traffic carry full highway rights for all users including motorists; • Restricted byways are open to those that can use a bridleway and non- motorised vehicles (such as a horse and cart). 27 All public rights of way are legally open to mobility vehicles for disabled people. However, many public rights of way (especially many footpaths) are not physically available to mobility vehicles (see 5.6). 4.1.3 The introduction of geographic information systems (computerised or digitised mapping) and GPS (global positioning system) means that there is greater opportunity for public rights of way records to be updated more accurately. More detail on the use of computerised mapping can be found in 5.11. 4.1.4 The make up of the rights of way network differs greatly between the South Downs and the rest of the county. -

WIRG Data Site

WIRG Data Site http://www.wirgdata.org/printsite.cgi?page=printsite&siteid=-1 www.wirgdata.org Found 89 results Site Name: Badland Wood OS Reference: TQ 7739 2134 Parish: Ewhurst Former Parish: Hundred: District: Rother County: East Sussex River Basin: Rother Site Type: Bloomery Period: Roman Century: 01 Geology: Ashdown Beds Geology notes: Earliest Date: Latest Date: Dating evidence: Two sherds, pieces of the same pot, of East Sussex Ware. A likely date is in the 1st century AD. Site Description: The bloomery site was discovered when a path was bulldozed through woodland. Fragments of iron slag and furnace lining were noticed. The site is immediately to the S of a small stream. Scheduled HER Reference: MES3874 Monument Number: Bay Height (m.): Bay Length (m.): Classis Britannica No Samian pottery: No tiles: Cylindrical slag No Two-finery forge: No plugs: Excavation?: Yes Excavation Three trenches were excavated; the first into the newly-bulldozed path, where Details: remains were found of a bloomery furnace constructed in an elongated bowl-shaped pit. Two trenches were dug into the slag heap, which comprised tap slag, vitrified furnace lining and undiagnostic slag. Description of site Woodland vegetation: Slag Heap Area Slag heap grade 2 (m. sq) : (Hodgkinson 1999): Persons Involved HAARG (1979) in Discovery: Lab Analysis of No View Lab Analysis Residues: Details: References: Jones, G.. (1980) Badlands bloomery, Ewhurst. Recologea Papers. 7. 2. pp. 35-7 Hodgkinson, J. S.. (1999) Romano-British iron production in the Sussex and Kent Weald: a review of current data. Historical Metallurgy. 33, no. 2. pp. 68-72 (for this site see page(s) 70) Cleere, H.