Congeries in the Backcountry James Andrew Stewart University of South Carolina - Columbia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Whispers from the Past

Whispers from the Past Overview Native Americans have been inhabitants of South Carolina for more than 15,000 years. These people contributed in countless ways to the state we call home. The students will be introduced to different time periods in the history of Native Americans and then focus on the Cherokee Nation. Connection to the Curriculum Language Arts, Geography, United States History, and South Carolina History South Carolina Social Studies Standards 8-1.1 Summarize the culture, political systems, and daily life of the Native Americans of the Eastern Woodlands, including their methods of hunting and farming, their use of natural resources and geographic features, and their relationships with other nations. 8-1.2 Categorize events according to the ways they improved or worsened relations between Native Americans and European settlers, including alliances and land agreements between the English and the Catawba, Cherokee, and Yemassee; deerskin trading; the Yemassee War; and the Cherokee War. Social Studies Literacy Elements F. Ask geographic questions: Where is it located? Why is it there? What is significant about its location? How is its location related to that of other people, places, and environments? I. Use maps to observe and interpret geographic information and relationships P. Locate, gather, and process information from a variety of primary and secondary sources including maps S. Interpret and synthesize information obtained from a variety of sources—graphs, charts, tables, diagrams, texts, photographs, documents, and interviews Time One to two fifty-minute class periods Materials South Carolina: An Atlas Computer South Carolina Interactive Geography (SCIG) CD-ROM Handouts included with lesson plan South Carolina Highway Map Dry erase marker Objectives 1. -

Tuscarora Trails: Indian Migrations, War, and Constructions of Colonial Frontiers

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2007 Tuscarora trails: Indian migrations, war, and constructions of colonial frontiers Stephen D. Feeley College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Feeley, Stephen D., "Tuscarora trails: Indian migrations, war, and constructions of colonial frontiers" (2007). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623324. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-4nn0-c987 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tuscarora Trails: Indian Migrations, War, and Constructions of Colonial Frontiers Volume I Stephen Delbert Feeley Norcross, Georgia B.A., Davidson College, 1996 M.A., The College of William and Mary, 2000 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Lyon Gardiner Tyler Department of History The College of William and Mary May, 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. APPROVAL SHEET This dissertation is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Stephen Delbert F eele^ -^ Approved by the Committee, January 2007 MIL James Axtell, Chair Daniel K. Richter McNeil Center for Early American Studies 11 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

The Relations of the Cherokee Indians with the English in America Prior to 1763

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 12-1923 The Relations of the Cherokee Indians with the English in America Prior to 1763 David P. Buchanan University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Political History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Buchanan, David P., "The Relations of the Cherokee Indians with the English in America Prior to 1763. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 1923. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/98 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by David P. Buchanan entitled "The Relations of the Cherokee Indians with the English in America Prior to 1763." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in . , Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: ARRAY(0x7f7024cfef58) Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) THE RELATIONS OF THE CHEROKEE Il.J'DIAUS WITH THE ENGLISH IN AMERICA PRIOR TO 1763. -

© 2015 Robert Daiutolo, Jr. All RIGHTS RESERVED

© 2015 Robert Daiutolo, Jr. All RIGHTS RESERVED GEORGE CROGHAN: THE LIFE OF A CONQUEROR by ROBERT DAIUTOLO, JR. A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School—New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History Written under the direction of Jan Lewis and approved by _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION George Croghan: The Life of a Conqueror By ROBERT DAIUTOLO, JR. Dissertation Director: Jan Lewis This dissertation integrates my own specifying paradigm of “situational frontier” and his- torian David Day’s generalizing paradigm of “supplanting society” to contextualize one historical personage, George Croghan, who advanced the interests of four eighteenth-cen- tury supplanting societies—one nation (Great Britain) and three of its North American colonies (Pennsylvania, New York, and Virginia)—in terms of three fields of endeavor, trade, diplomacy, and proprietorship. Croghan was an Irish immigrant who, during his working life on the “situational frontiers” of North America, mastered the intricacies of intercultural trade and diplomacy. His mastery of both fields of endeavor enabled him not only to create advantageous conditions for the governments of the three colonies to claim proprietorship of swaths of Indian land, but also to create advantageous conditions for himself to do likewise. The loci of his and the three colonies’ claims were the “situa- tional frontiers” themselves, the distinct spaces where particular Indians, Europeans, and Euro-Americans converged in particular circumstances and coexisted, sometimes peace- fully and sometimes violently. His mastery of intercultural trade and diplomacy enabled him as well to create advantageous conditions for Great Britain to claim proprietorship in the Old Northwest (present-day Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin, Indiana, and Illinois) and for himself to do likewise. -

Hunting Shirts and Silk Stockings: Clothing Early Cincinnati

Fall 1987 Clothing Early Cincinnati Hunting Shirts and Silk Stockings: Clothing Early Cincinnati Carolyn R. Shine play function is the more important of the two. Shakespeare, that fount of familiar quotations and universal truths, gave Polonius these words of advice for Laertes: Among the prime movers that have shaped Costly thy habit as thy purse can buy, But not expressed infancy; history, clothing should be counted as one of the most potent, rich not gaudy; For the apparel oft proclaims the man.1 although its significance to the endless ebb and flow of armed conflict tends to be obscured by the frivolities of Laertes was about to depart for the French fashion. The wool trade, for example, had roughly the same capital where, then as now, clothing was a conspicuous economic and political significance for the Late Middle indicator of social standing. It was also of enormous econo- Ages that the oil trade has today; and, closer to home, it was mic significance, giving employment to farmers, shepherds, the fur trade that opened up North America and helped weavers, spinsters, embroiderers, lace makers, tailors, button crack China's centuries long isolation. And think of the Silk makers, hosiers, hatters, merchants, sailors, and a host of others. Road. Across the Atlantic and nearly two hundred If, in general, not quite so valuable per pound years later, apparel still proclaimed the man. Although post- as gold, clothing like gold serves as a billboard on which to Revolution America was nominally a classless society, the display the image of self the individual wants to present to social identifier principle still manifested itself in the quality the world. -

Georgia Genealogy Research Websites Note: Look for the Genweb and Genealogy Trails of the County in Which Your Ancestor Lived

Genealogy Research in Georgia Early Native Americans in Georgia Native inhabitants of the area that is now Georgia included: *The Apalachee Indians *The Cherokee Indians *The Hitchiti, Oconee and Miccosukee Indians *The Muskogee Creek Indians *The Timucua Indians *The Yamasee and Guale Indians In the late 1700’s and early 1800’s, most of these tribes were forced to cede their land to the U.S. government. The members of the tribes were “removed” to federal reservations in the western U.S. In the late 1830’s, remaining members of the Cherokee tribes were forced to move to Oklahoma in what has become known as the “Trail of Tears.” Read more information about Native Americans of Georgia: http://www.native-languages.org/georgia.htm http://www.ourgeorgiahistory.com/indians/ http://www.aboutnorthgeorgia.com/ang/American_Indians_of_Georgia Some native people remained in hiding in Georgia. Today, the State of Georgia recognizes the three organizations of descendants of these people: The Cherokee Indians of Georgia: PO Box 337 St. George, GA 31646 The Georgia Tribe of Eastern Cherokee: PO Box 1993, Dahlonega, Georgia 30533 or PO Box 1915, Cumming, GA 30028 http://www.georgiatribeofeasterncherokee.com/ The Lower Muscogee Creek Tribe: Rte 2, PO Box 370 Whigham, GA 31797 First People - Links to State Recognized Tribes, sorted by state - http://www.firstpeople.us/FP-Html-Links/state- recognized-tribes-in-usa-by-state.html European Settlement of Georgia Photo at left shows James Oglethorpe landing in what is now called Georgia 1732: King George II of England granted a charter to James Oglethorpe for the colony of Georgia to be a place of refuge. -

A Study of the Cherokee Indians' Clothing Practices and History for the Period 1654 to 1838

A STUDY OF THE CHEROKEE INDIANS' CLOTHING PRACTICES AND HISTORY FOR THE PERIOD 1654 TO 1838 By EDNA GERALDINE SAUNDERS /, ··,r / Bachelor of Science New Mexico State University Las Cruces, New Mexico 1963 Submitted to the faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma $tate University in partial fulfillment 9f the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE May, •. 1969 OKlM-l'OMA STATE llWWlititW\' l-1 Sf"iAr~Y t ·SEP ~~ tlil l. ,·.,~· ... _,;'·.-s=><'• . A STUDY OF THE CHEROKEE INDIANS' CLOTHING PRACTICES AND HISTORY FOR THE PERIOD 16.54 TO 1838 Thesis Approved: ad~~· Thesis · Adviser fJ. n . 1-w,kwr Dean of the Graduate College ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . The author wishes to th.ank Miss Dorothy Saville for her help and · especially her patience during the writing .of this thesis; Miss· S.ara Meador for her valuable suggestiops; Pr. Nick Stinnett for his willingness to help in time of need; and Dr. Donice Hawes for serv ing as a member of the advisory coI!llnittee; and Dr. Edna Meshke for. the original idea.. Appreciation is also expressed to Patrick Patterson of the Woola.roc· Museum; Mrs. Ma.:rtha Blaine and the library staff at the Ok::\.ahoma His..., torieal Society; and to t.he staff of the Five Civilized Tribes Museum in Muskogee. The writer also thanks her many friends and fellow students who were interested and encouraging in this undertaking. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page INTRODUCTION 1 Purpose of the Study . , , . 3 II. HISTORICAL SKETCH OF THE CHEROKEES 4 III. CLOTHING MATERIALS AND THEIR USAGE " 0 • • . -

Tsalagiyi Nvdagi Tribal Minutes of April 17Th, 2021

Tsalagiyi Nvdagi Meeting Minutes April 17th, 2021 Meeting held on Land of Spirits led by UGU Ron Black Eagle Trussell. Present were: UGU Ron Black Eagle Trussell Deputy Chief John Laughing Bear Stephenson Treaty District Chief Jennifer Spirit Wolf Forest Central District Chief Kassa Eagle Wolf Willingham Justice Council Arlie Path Maker Bice Sharon Evening Deer Bice Jack Thunder Hawk Sheridan Brenda Nature Woman Sheridan Laura Kamama Buchmann Elisha Grey Wolf Buchmann Lily Little Hawk Forest Present by Proxie: Northeastern District Chief Ramona Yellow Buffalo Calf Woman TePaske Southern District Chief John Big Sky Garcia At Large District Chief William Crazy Bear Hoff Absent: Northern District Chief Tom Adcox Pacific Northwest Chief Chet McVay Meeting started at 1:00 PM. All were smudged prior to the meeting. Treasurers Report: As of March 31st,2021 Total is $6076.02 A letter from Chief Hoff who is our representative to National Congress of American Indians (NCAI), had attended a virtual meeting by Zoom, on February 21, 2021, and was informed that our Tribe is now listed in the Southwestern Plains Region, having been moved from the Southeastern Region. This is to more accurately reflect our geographic location. The National Conference which was to be held in Alaska, in June, will now be a virtual conference. The new Secretary of the Interior will be a woman of native descent. At Large District Chief William Crazy Bear Hoff is purchasing and paying for the installation of a 12 foot by 20 foot carport to be installed on The Land of Spirits, once the ground is leveled and prepped for the work to be done. -

Cherokee from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia • Ten Things You May Not Know About Wikipedia •Jump To: Navigation, Search This Page Contains Special Characters

Cherokee From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia • Ten things you may not know about Wikipedia •Jump to: navigation, search This page contains special characters. Because of technical limitations, some web browsers may not display these glyphs properly. More info… ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯ Cherokee Flag of the Cherokee Nation Flag of the United Keetoowah Band. Flag of the Eastern Band Cherokee Total population 320,000+ Regions with significant populations Federally Enrolled members: Cherokee Nation (f): 270,000+ United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians, Oklahoma (f): 10,000 Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, North Carolina (f): 10,000+ (f) = federally recognized Language(s) English, Cherokee Religion(s) Christianity (Southern Baptist and Methodist), Traditional Ah-ni-yv-wi-ya, other small Christian groups. Related ethnic groups American Indians, Five Civilized Tribes, Tuscarora, other Iroquoians. For other uses, see Cherokee (disambiguation). The Cherokee ( ah-ni-yv-wi-ya {Unicode: ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯ} in the Cherokee language) are a native people from North America, who at the time of European contact in the sixteenth century, inhabited what is now the Eastern and Southeastern United States. Most were forcibly moved westward to the Ozark Plateau in the 1830s. They are one of the tribes referred to as the Five Civilized Tribes. According to the 2000 U.S. Census, they are the largest of the 563 federally recognized Native American tribes in the United States. [1] The Cherokee refer to themselves as Tsa-la-gi (pronounced "chaw-la-gee") or A-ni-yv-wi-ya (pronounced "ah knee yuh wee yaw", literal translation: "Principle People"). In 1654, the Powhatan were referring to this people as the Rickahockan. -

Early Historic Culture 165 Clothing the Indians Who Lived in Louisiana Wore Simple Clothing Made from Available Materials

Section33 Early HistoricHistoric Culture As you read, look for: • elements of Native American culture, and • vocabulary terms pirogue and calumet. Below: This painting by When the first Europeans came to Louisiana, the American Indians who were Francois Barnard, “Choctaw living here had a rich culture. Village near the Chefuncte,” provides an opportunity The Village for us to see history through Community life was organized around a tribe or a clan, which was headed the eyes of a person who by a chief or chiefs. Kinship was very important and, along with social class, actually lived it. directed much of a person’s life. 164 Chapter 5 Louisiana’s Early People: Natives and Newcomers Membership in clans was passed through the mother’s side of the family. The Above: The Choctaw played Caddo and the Tunica ranked the clans, with some more powerful than others, ball games as a form of and chiefs chosen only from specific clans. The Natchez had a caste (class) sys- recreation as well as to help tem with several levels. Moving into a higher group was possible through mar- them improve their skills riage, but a person could also lose rank by marriage. The Chitimacha followed a for hunting and war. George true caste system, in which people married only within their own class. Catlin caught the spirit of Children were raised in these groups, often under the care of all the adults. these games in his painting In some tribes, the mother’s brother handled discipline, and the father’s role “Choctaw Ball Game.” was more like a big brother. -

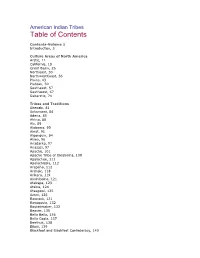

Table of Contents

American Indian Tribes Table of Contents Contents-Volume 1 Introduction, 3 Culture Areas of North America Arctic, 11 California, 19 Great Basin, 26 Northeast, 30 NorthwestCoast, 36 Plains, 43 Plateau, 50 Southeast, 57 Southwest, 67 Subarctic, 74 Tribes and Traditions Abenaki, 81 Achumawi, 84 Adena, 85 Ahtna, 88 Ais, 89 Alabama, 90 Aleut, 91 Algonquin, 94 Alsea, 96 Anadarko, 97 Anasazi, 97 Apache, 101 Apache Tribe of Oklahoma, 108 Apalachee, 111 Apalachicola, 112 Arapaho, 112 Archaic, 118 Arikara, 119 Assiniboine, 121 Atakapa, 123 Atsina, 124 Atsugewi, 125 Aztec, 126 Bannock, 131 Bayogoula, 132 Basketmaker, 132 Beaver, 135 Bella Bella, 136 Bella Coola, 137 Beothuk, 138 Biloxi, 139 Blackfoot and Blackfeet Confederacy, 140 Caddo tribal group, 146 Cahuilla, 153 Calusa, 155 CapeFear, 156 Carib, 156 Carrier, 158 Catawba, 159 Cayuga, 160 Cayuse, 161 Chasta Costa, 163 Chehalis, 164 Chemakum, 165 Cheraw, 165 Cherokee, 166 Cheyenne, 175 Chiaha, 180 Chichimec, 181 Chickasaw, 182 Chilcotin, 185 Chinook, 186 Chipewyan, 187 Chitimacha, 188 Choctaw, 190 Chumash, 193 Clallam, 194 Clatskanie, 195 Clovis, 195 CoastYuki, 196 Cocopa, 197 Coeurd'Alene, 198 Columbia, 200 Colville, 201 Comanche, 201 Comox, 206 Coos, 206 Copalis, 208 Costanoan, 208 Coushatta, 209 Cowichan, 210 Cowlitz, 211 Cree, 212 Creek, 216 Crow, 222 Cupeño, 230 Desert culture, 230 Diegueño, 231 Dogrib, 233 Dorset, 234 Duwamish, 235 Erie, 236 Esselen, 236 Fernandeño, 238 Flathead, 239 Folsom, 242 Fox, 243 Fremont, 251 Gabrielino, 252 Gitksan, 253 Gosiute, 254 Guale, 255 Haisla, 256 Han, 256 -

Theodore De Bry's Timucua Engravings

“Timucua Technology” - A Middle Grade Florida Curriculum Theodore de Bry’s Timucua Engravings – Fact or Fiction? Students discover how an inaccurate interpretation of historical documents can have far-reaching consequences. STUDENT LEARNING GOAL: Students will review and understand evidence that indicates that de Bry’s engravings of native peoples in the New World were intended as exciting travel tales and religious propaganda, not as reflections of reality. SUNSHINE STATE STANDARDS ASSESSED: Social Studies • SS.8.A.1.2 Analyze charts, graphs, maps, photographs and timelines; analyze political cartoons; determine cause and effect. • SS.8.A.1.7 View historic events through the eyes of those who were there as shown in their art, writings, music, and artifacts. • SS.8.A.2.1 Compare the relationships among the British, French, Spanish, and Dutch in their struggle for colonization of North America. Language Arts • LA.7.1.6.2 The student will listen to, read, and discuss familiar and conceptually challenging text. • LA.7.4.2.2 The student will record information (e.g., observations, notes, lists, charts, legends) related to a topic, including visual aids to organize and record information, as appropriate, and attribute sources of information. • LA.8.1.6.2 The student will listen to, read, and discuss familiar and conceptually challenging text. • LA.8.4.2.2 The student will record information (e.g., observations, notes, lists, charts, legends) related to a topic, including visual aids to organize and record information, as appropriate, and attribute sources of information. • LA.8.6.4.1 The student will use appropriate available technologies to enhance communication and achieve a purpose (e.g., video, digital technology).