If All Else Fails: the Challenges of Containing a Nuclear-Armed Iran

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Being Lesbian in Iran

Human Rights Report Being Lesbian in Iran Human Rights Report: Being Lesbian in Iran 1 About OutRight Every day around the world, LGBTIQ people’s human rights and dignity are abused in ways that shock the conscience. The stories of their struggles and their resilience are astounding, yet remain unknown—or willfully ignored—by those with the power to make change. OutRight Action International, founded in 1990 as the International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission, works alongside LGBTIQ people in the Global South, with offices in six countries, to help identify community-focused solutions to promote policy for lasting change. We vigilantly monitor and document human rights abuses to spur action when they occur. We train partners to expose abuses and advocate for themselves. Headquartered in New York City, OutRight is the only global LGBTIQ-specific organization with a permanent presence at the United Nations in New York that advocates for human rights progress for LGBTIQ people. [email protected] https://www.facebook.com/outrightintl http://twitter.com/outrightintl http://www.youtube.com/lgbthumanrights http://OutRightInternational.org/iran OutRight Action International 80 Maiden Lane, Suite 1505, New York, NY 10038 U.S.A. P: +1 (212) 430.6054 • F: +1 (212) 430.6060 This work may be reproduced and redistributed, in whole or in part, without alteration and without prior written permission, solely for nonprofit administrative or educational purposes provided all copies contain the following statement: © 2016 OutRight Action International. This work is reproduced and distributed with the permission of OutRight Action International. No other use is permitted without the express prior written permission of OutRight Action International. -

Iran's Gray Zone Strategy

Iran’s Gray Zone Strategy Cornerstone of its Asymmetric Way of War By Michael Eisenstadt* ince the creation of the Islamic Republic in 1979, Iran has distinguished itself (along with Russia and China) as one of the world’s foremost “gray zone” actors.1 For nearly four decades, however, the United States has struggled to respond effectively to this asymmetric “way of war.” Washington has often Streated Tehran with caution and granted it significant leeway in the conduct of its gray zone activities due to fears that U.S. pushback would lead to “all-out” war—fears that the Islamic Republic actively encourages. Yet, the very purpose of this modus operandi is to enable Iran to pursue its interests and advance its anti-status quo agenda while avoiding escalation that could lead to a wider conflict. Because of the potentially high costs of war—especially in a proliferated world—gray zone conflicts are likely to become increasingly common in the years to come. For this reason, it is more important than ever for the United States to understand the logic underpinning these types of activities, in all their manifestations. Gray Zone, Asymmetric, and Hybrid “Ways of War” in Iran’s Strategy Gray zone warfare, asymmetric warfare, and hybrid warfare are terms that are often used interchangeably, but they refer neither to discrete forms of warfare, nor should they be used interchangeably—as they often (incor- rectly) are. Rather, these terms refer to that aspect of strategy that concerns how states employ ways and means to achieve national security policy ends.2 Means refer to the diplomatic, informational, military, economic, and cyber instruments of national power; ways describe how these means are employed to achieve the ends of strategy. -

Prism Vol. 9, No. 2 Prism About Vol

2 021 PRISMVOL. 9, NO. 2 | 2021 PRISM VOL. 9, NO. 2 NO. 9, VOL. THE JOURNAL OF COMPLEX OPER ATIONS PRISM ABOUT VOL. 9, NO. 2, 2021 PRISM, the quarterly journal of complex operations published at National Defense University (NDU), aims to illuminate and provoke debate on whole-of-government EDITOR IN CHIEF efforts to conduct reconstruction, stabilization, counterinsurgency, and irregular Mr. Michael Miklaucic warfare operations. Since the inaugural issue of PRISM in 2010, our readership has expanded to include more than 10,000 officials, servicemen and women, and practi- tioners from across the diplomatic, defense, and development communities in more COPYEDITOR than 80 countries. Ms. Andrea L. Connell PRISM is published with support from NDU’s Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS). In 1984, Secretary of Defense Casper Weinberger established INSS EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS within NDU as a focal point for analysis of critical national security policy and Ms. Taylor Buck defense strategy issues. Today INSS conducts research in support of academic and Ms. Amanda Dawkins leadership programs at NDU; provides strategic support to the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, combatant commands, and armed services; Ms. Alexandra Fabre de la Grange and engages with the broader national and international security communities. Ms. Julia Humphrey COMMUNICATIONS INTERNET PUBLICATIONS PRISM welcomes unsolicited manuscripts from policymakers, practitioners, and EDITOR scholars, particularly those that present emerging thought, best practices, or train- Ms. Joanna E. Seich ing and education innovations. Publication threshold for articles and critiques varies but is largely determined by topical relevance, continuing education for national and DESIGN international security professionals, scholarly standards of argumentation, quality of Mr. -

Iran: Ethnic and Religious Minorities

Order Code RL34021 Iran: Ethnic and Religious Minorities Updated November 25, 2008 Hussein D. Hassan Information Research Specialist Knowledge Services Group Iran: Ethnic and Religious Minorities Summary Iran is home to approximately 70.5 million people who are ethnically, religiously, and linguistically diverse. The central authority is dominated by Persians who constitute 51% of Iran’s population. Iranians speak diverse Indo-Iranian, Semitic, Armenian, and Turkic languages. The state religion is Shia, Islam. After installation by Ayatollah Khomeini of an Islamic regime in February 1979, treatment of ethnic and religious minorities grew worse. By summer of 1979, initial violent conflicts erupted between the central authority and members of several tribal, regional, and ethnic minority groups. This initial conflict dashed the hope and expectation of these minorities who were hoping for greater cultural autonomy under the newly created Islamic State. The U.S. State Department’s 2008 Annual Report on International Religious Freedom, released September 19, 2008, cited Iran for widespread serious abuses, including unjust executions, politically motivated abductions by security forces, torture, arbitrary arrest and detention, and arrests of women’s rights activists. According to the State Department’s 2007 Country Report on Human Rights (released on March 11, 2008), Iran’s poor human rights record worsened, and it continued to commit numerous, serious abuses. The government placed severe restrictions on freedom of religion. The report also cited violence and legal and societal discrimination against women, ethnic and religious minorities. Incitement to anti-Semitism also remained a problem. Members of the country’s non-Muslim religious minorities, particularly Baha’is, reported imprisonment, harassment, and intimidation based on their religious beliefs. -

Iran and Israel's National Security in the Aftermath of 2003 Regime Change in Iraq

Durham E-Theses IRAN AND ISRAEL'S NATIONAL SECURITY IN THE AFTERMATH OF 2003 REGIME CHANGE IN IRAQ ALOTHAIMIN, IBRAHIM,ABDULRAHMAN,I How to cite: ALOTHAIMIN, IBRAHIM,ABDULRAHMAN,I (2012) IRAN AND ISRAEL'S NATIONAL SECURITY IN THE AFTERMATH OF 2003 REGIME CHANGE IN IRAQ , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4445/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 . IRAN AND ISRAEL’S NATIONAL SECURITY IN THE AFTERMATH OF 2003 REGIME CHANGE IN IRAQ BY: IBRAHIM A. ALOTHAIMIN A thesis submitted to Durham University in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy DURHAM UNIVERSITY GOVERNMENT AND INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS March 2012 1 2 Abstract Following the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, Iran has continued to pose a serious security threat to Israel. -

Reimagining US Strategy in the Middle East

REIMAGININGR I A I I G U.S.S STRATEGYT A E Y IIN THET E MMIDDLED L EEASTS Sustainable Partnerships, Strategic Investments Dalia Dassa Kaye, Linda Robinson, Jeffrey Martini, Nathan Vest, Ashley L. Rhoades C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RRA958-1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0662-0 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. 2021 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover composite design: Jessica Arana Image: wael alreweie / Getty Images Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface U.S. -

Iran's “Second” Islamic Revolution

IRAN’S “SECOND” ISLAMIC REVOLUTION: ITS CHALLENGE TO THE WEST Brig.-Gen. (ret.) Dr. Shimon Shapira and Daniel Diker Iranian President Mahmoud The ideological engine powering the Iranian re- via what is known in the West as “Gog and Magog” Ahmadinejad delivers gime’s race for regional supremacy is among the events is driven by his spiritual fealty to the fun- a speech on the 18th more misunderstood – and ignored – aspects of damentalist Ayatollah Mohammad Mesbah Yazdi anniversary of the death Iran’s political and military activity in the Middle and the messianic Hojjatiyeh organization. These of the late revolutionary East. Particularly since the election of Mahmoud religious convictions have propelled the regime founder Ayatollah Khomeini, Ahmadinejad to the presidency in 2005, Iran’s revo- toward an end-of-days scenario that Khomeini had under his portrait, at his 3 mausoleum just outside lutionary leadership has thrust the Islamic Republic sought to avoid. Tehran, Iran, June 3, 2007. into the throes of what has been called a “Second 1 Hard-line Ahmadinejad said Islamic Revolution.” In its basic form, this revolu- Iran’s Second Islamic Revolution is distinguishing the world would witness the tion seeks a return to the principles of former Ira- itself from the original Islamic Revolution in other destruction of Israel soon, nian leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s 1979 important ways: Iran is not only spreading its pow- the official Islamic Republic Islamic Revolution, which was based on: destroy- er in the region by reaching out to Shiite communi- News Agency reported. ing Israel – “the Little Satan” – as a symbol of the ties such as in Iraq and Lebanon, the regime is also United States, “the Great Satan;”2 exporting the actively cooperating with Sunni terror groups in an Islamic revolution domestically and against Arab effort to solicit support from the Sunni Arab street “apostate” governments in the region, and forc- over the heads of established Arab governments. -

The Annals of Unsolved Crime by Edward Jay Epstein Isbn: 9781612190488

THE ANNALS OF UNSOLVED CRIME BY EDWARD JAY EPSTEIN ISBN: 9781612190488 Available at mhpbooks.com and wherever books are sold. THE ANNALS OF UNSOLVED CRIME BY EDWARD JAY EPSTEIN MELVILLE HOUSE BROOKLYN • LONDON CONTENTS PREFACE 5 PART ONE “LONERS”: BUT WERE THEY ALONE? 1. The Assassination of President Lincoln 21 2. The Reichstag Fire 29 3. The Lindbergh Kidnapping 35 4. The Assassination of Olof Palme 43 5. The Anthrax Attack on America 47 6. The Pope’s Assassin 59 PART TWO SUICIDE, ACCIDENT, OR DISGUISED MURDER? 7. The Mayerling Incident 65 8. Who Killed God’s Banker? 69 9. The Death of Dag Hammarskjöld 97 10. The Strange Death of Marilyn Monroe 103 11. The Crash of Enrico Mattei 109 12. The Disappearance of Lin Biao 113 13. The Elimination of General Zia 117 14. The Submerged Spy 131 PART THREE COLD CASE FILE 15. Jack the Ripper 139 16. The Harry Oakes Murder 145 17. The Black Dahlia 151 18. The Pursuit of Dr. Sam Sheppard 155 19. The Killing of JonBenet Ramsey 161 20. The Zodiac 165 21. The Vanishing of Jimmy Hoffa 169 2 EDWARD JAY EPSTEIN PART FOUR CRIMES OF STATE 22. Death in Ukraine: The Case of the Headless Journalist 177 23. The Dubai Hit 189 24. The Beirut Assassination 195 25. Who Assassinated Anna Politkovskaya? 201 26. Blowing Up Bhutto 205 27. The Case of the Radioactive Corpse 209 28. The Godfather Contract 231 29. The Vanishings 237 PART FIVE SOLVED OR UNSOLVED? 30. The Oklahoma City Bombing 245 31. The O. J. -

Escalation Control and the Nuclear Option in South Asia

Escalation Control and the Nuclear Option in South Asia Michael Krepon, Rodney W. Jones, and Ziad Haider, editors Copyright © 2004 The Henry L. Stimson Center All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission in writing from the Henry L. Stimson Center. Cover design by Design Army. ISBN 0-9747255-8-7 The Henry L. Stimson Center 1111 19th Street NW Twelfth Floor Washington, DC 20036 phone 202.223.5956 fax 202.238.9604 www.stimson.org Table of Contents Preface ................................................................................................................. v Abbreviations..................................................................................................... vii Introduction......................................................................................................... ix 1. The Stability-Instability Paradox, Misperception, and Escalation Control in South Asia Michael Krepon ............................................................................................ 1 2. Nuclear Stability and Escalation Control in South Asia: Structural Factors Rodney W. Jones......................................................................................... 25 3. India’s Escalation-Resistant Nuclear Posture Rajesh M. Basrur ........................................................................................ 56 4. Nuclear Signaling, Missiles, and Escalation Control in South Asia Feroz Hassan Khan ................................................................................... -

Crude Oil for Natural Gas: Prospects for Iran-Saudi Reconciliation

Atlantic Council GLOBAL ENERGY CENTER ISSUE BRIEF BY JEAN-FRANCOIS SEZNEC Crude Oil for Natural Gas Prospects for Iran-Saudi Reconciliation OCTOBER 2015 The relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia are often presented as an intractable struggle between powers Global Energy Center - tions: Shia in Iran and Sunni in Saudi Arabia.1 The Saudis feelthat threatenedfind legitimacy by what in their they respective consider anIslamic encroaching tradi At a time of unprecedented volatility and opportunity, the Atlantic Council Global Energy 2 The Center works to promote global access to affordable, “Shia crescent” of Iranian influence, extending from reliable, and sustainable energy. al-Sham (Syria-Lebanon) to Iraq, Iran, and Yemen. Alongside government, industry, and civil society House of Saud, in particular, views this “crescent” as an- partners, the Center devises creative responses attempt to bring an end to its stewardship of Islam’s to helpenergy-related develop energy geopolitical strategies conflicts, and policies advances that stretchingholiest sites across and replace the states it with of the Shia Gulf supervision. Cooperation Simi sustainable energy solutions, and identifies trends larly, Iran fears the threat of encircling Sunni influence, ensure long-term prosperity and security. Council (GCC), through to Egypt, Jordan, Pakistan, and parts of Syria. Certainly, the death of many hundreds than they appear. Saudi Arabia’s use of a sectarian soldiersof Hajjis tofrom the Iran Syrian and front other a fewcountries days later in Mecca are creat on - narrative to describe the 2011 uprising in Bahrain ingSeptember great tensions 24, 2015, between as well the as twothe dispatch Gulf giants. of Iranian Further and Iran’s self-appointed role as the champion of Shia rights underline how sectarian rhetoric has primarily thebeen opposing utilized bystate. -

Aibs-Shortlist-2-2020.Pdf

The AIBs 2020 The Shortlist TV and VIDEO Arts and culture The Dancer Thieves Banyak Films for Witness, Al Jazeera English The Red Door Project: Evolve Blue Chalk Media for The Red Door Project Spirit of Tokyo CNN Beethoven’s Ninth: Symphony for the World Deutsche Welle Matera Traveller Iran International Miyako, The Last Dance NHK in association with NHK Enterprises Chinese Folk Opera Phoenix Satellite Television Human interest MENtal Health: Breaking the Silence 5 News, ITN Fly on the Wall: The Virus Al Jazeera English Online Word of Truth: Transgender Arabs Living in the Middle East Alhurra Television African Voices: Female Pilots CNN Surviving the Special Forces De Mensen PANO: Secret on Instagram één for VRT Off the Grid: Missing Babies TRT World The Skin we Wear Very! For CNA, Mediacorp Pte Ltd Supporters of the AIBs 2020 The AIBs 2020 The Shortlist Natural world Fault Lines - Amazon Burning: Death and Destruction in Brazil’s Rainforest Al Jazeera English Borneo is Burning CNN Chris Packham: Plant A Tree to Save the World ITN Productions Sinking Island Radio Free Asia Freed to be Wild RT VOA Films: Illegal Logging Inside Mexico Monarch Butterfly Sanctuary VOA (Voice of America) Australia's Ocean Odyssey: A Journey Down the Wild Pacific Media for Australian Broadcasting East Australian Current Corporation and ARTE France Science and technology The Big Picture: The World According to A.I. Al Jazeera English Refugee Gardens: Turning Old Mattresses into Fresh Food BBC News Inventing Tomorrow CNN WFH: New Reality CNN Coded World Peddling -

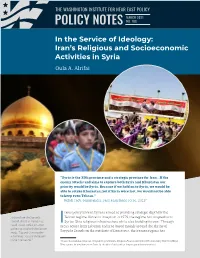

Policy Notes March 2021

THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY MARCH 2021 POLICY NOTES NO. 100 In the Service of Ideology: Iran’s Religious and Socioeconomic Activities in Syria Oula A. Alrifai “Syria is the 35th province and a strategic province for Iran...If the enemy attacks and aims to capture both Syria and Khuzestan our priority would be Syria. Because if we hold on to Syria, we would be able to retake Khuzestan; yet if Syria were lost, we would not be able to keep even Tehran.” — Mehdi Taeb, commander, Basij Resistance Force, 2013* Taeb, 2013 ran’s policy toward Syria is aimed at providing strategic depth for the Pictured are the Sayyeda Tehran regime. Since its inception in 1979, the regime has coopted local Zainab shrine in Damascus, Syrian Shia religious infrastructure while also building its own. Through youth scouts, and a pro-Iran I proxy actors from Lebanon and Iraq based mainly around the shrine of gathering, at which the banner Sayyeda Zainab on the outskirts of Damascus, the Iranian regime has reads, “Sayyed Commander Khamenei: You are the leader of the Arab world.” *Quoted in Ashfon Ostovar, Vanguard of the Imam: Religion, Politics, and Iran’s Revolutionary Guards (2016). Khuzestan, in southwestern Iran, is the site of a decades-long separatist movement. OULA A. ALRIFAI IRAN’S RELIGIOUS AND SOCIOECONOMIC ACTIVITIES IN SYRIA consolidated control over levers in various localities. against fellow Baathists in Damascus on November Beyond religious proselytization, these networks 13, 1970. At the time, Iran’s Shia clerics were in exile have provided education, healthcare, and social as Muhammad Reza Shah Pahlavi was still in control services, among other things.