Lake Woodruff National Wildlife Refuge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

40216Doc.Pdf

Florida Administrative Register Volume 40, Number 216, November 5, 2014 Section I Section II Notice of Development of Proposed Rules Proposed Rules and Negotiated Rulemaking COMMISSION ON ETHICS WATER MANAGEMENT DISTRICTS RULE NOS.: RULE TITLES: Southwest Florida Water Management District 34-12.200 Registration Requirements RULE NO.: RULE TITLE: 34-12.210 Effective Date of Registration 40D-8.624 Guidance and Minimum Levels for Lakes 34-12.330 Annual Renewals PURPOSE AND EFFECT: The purpose is to amend Rule 40D- 34-12.400 Compensation Reporting Requirements 34-12.405 Penalties for Late Filing 8.624, F.A.C., to delete the previously adopted guidance levels, 34-12.420 Notification of Compensation Reporting and adopt new minimum and guidance levels for Lakes Hanna, Deadlines Keene, and Kell located in Hillsborough County. PURPOSE AND EFFECT: The purpose of the proposed new SUBJECT AREA TO BE ADDRESSED: Establish guidance rules is to update information regarding lobbyist registration via and minimum levels for Lakes Hanna, Keene and Kell pursuant electronic means, lobbyist renewal of registrations via to Section 373.042, F.S. electronic means, to provide the name and location of the RULEMAKING AUTHORITY: 373.044, 373.113, 373.171 electronic database to be used for filing executive branch FS. quarterly compensation reports, to update information LAW IMPLEMENTED: 373.036, 373.042, 373.0421, 373.086, pertaining to penalties for late filing executive branch quarterly 373.709 FS. compensation reports, and to update and re-adopt the forms IF REQUESTED IN WRITING AND NOT DEEMED adopted by reference in Chapter 34-12, F.A.C., to address UNNECESSARY BY THE AGENCY HEAD, A RULE changes necessary to comport with the new electronic database. -

Bill Baggs Cape Florida State Park

Haw Creek Preserve State Park Approved Plan Unit Management Plan STATE OF FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION Division of Recreation and Parks December 16, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................1 PURPOSE AND SIGNIFICANCE OF THE PARK ....................................... 1 Park Significance ................................................................................1 PURPOSE AND SCOPE OF THE PLAN..................................................... 2 MANAGEMENT PROGRAM OVERVIEW ................................................... 7 Management Authority and Responsibility .............................................. 7 Park Management Goals ...................................................................... 8 Management Coordination ................................................................... 8 Public Participation ..............................................................................9 Other Designations .............................................................................9 RESOURCE MANAGEMENT COMPONENT INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 11 RESOURCE DESCRIPTION AND ASSESSMENT..................................... 12 Natural Resources ............................................................................. 12 Topography .................................................................................. 12 Geology ...................................................................................... -

Do Worm Lizards Occur in Nebraska? Louis A

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in Herpetology Papers in the Biological Sciences 1993 Do Worm Lizards Occur in Nebraska? Louis A. Somma Florida State Collection of Arthropods, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciherpetology Part of the Biodiversity Commons, and the Population Biology Commons Somma, Louis A., "Do Worm Lizards Occur in Nebraska?" (1993). Papers in Herpetology. 11. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciherpetology/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in Herpetology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. @ o /' number , ,... :S:' .' ,. '. 1'1'13 Do Mono Li ••rel,. Occur ill 1!I! ..br .... l< .. ? by Louis A. Somma Department of- Zoology University of Florida Gainesville, FL 32611 Amphisbaenids, or worm lizards, are a small enigmatic suborder of reptiles (containing 4 families; ca. 140 species) within the order Squamata, which include~ the more speciose lizards and snakes (Gans 1986). The name amphisbaenia is derived from the mythical Amphisbaena (Topsell 1608; Aldrovandi 1640), a two-headed beast (one head at each end), whose fantastical description may have been based, in part, upon actual observations of living worm lizards (Druce 1910). While most are limbless and worm-like in appearance, members of the family Bipedidae (containing the single genus Sipes) have two forelimbs located close to the head. This trait, and the lack of well-developed eyes, makes them look like two-legged worms. -

Checklist Reptile and Amphibian

To report sightings, contact: Natural Resources Coordinator 980-314-1119 www.parkandrec.com REPTILE AND AMPHIBIAN CHECKLIST Mecklenburg County, NC: 66 species Mole Salamanders ☐ Pickerel Frog ☐ Ground Skink (Scincella lateralis) ☐ Spotted Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) palustris) Whiptails (Ambystoma maculatum) ☐ Southern Leopard Frog ☐ Six-lined Racerunner ☐ Marbled Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) sphenocephala (Aspidoscelis sexlineata) (Ambystoma opacum) (sphenocephalus)) Nonvenomous Snakes Lungless Salamanders Snapping Turtles ☐ Eastern Worm Snake ☐ Dusky Salamander (Desmognathus fuscus) ☐ Common Snapping Turtle (Carphophis amoenus) ☐ Southern Two-lined Salamander (Chelydra serpentina) ☐ Scarlet Snake1 (Cemophora coccinea) (Eurycea cirrigera) Box and Water Turtles ☐ Black Racer (Coluber constrictor) ☐ Three-lined Salamander ☐ Northern Painted Turtle ☐ Ring-necked Snake (Eurycea guttolineata) (Chrysemys picta) (Diadophis punctatus) ☐ Spring Salamander ☐ Spotted Turtle2, 6 (Clemmys guttata) ☐ Corn Snake (Pantherophis guttatus) (Gyrinophilus porphyriticus) ☐ River Cooter (Pseudemys concinna) ☐ Rat Snake (Pantherophis alleghaniensis) ☐ Slimy Salamander (Plethodon glutinosus) ☐ Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina) ☐ Eastern Hognose Snake ☐ Mud Salamander (Pseudotriton montanus) ☐ Yellow-bellied Slider (Trachemys scripta) (Heterodon platirhinos) ☐ Red Salamander (Pseudotriton ruber) ☐ Red-eared Slider3 ☐ Mole Kingsnake Newts (Trachemys scripta elegans) (Lampropeltis calligaster) ☐ Red-spotted Newt Mud and Musk Turtles ☐ Eastern Kingsnake -

Federal Register Notice

2100 Federal Register / Vol. 69, No. 9 / Wednesday, January 14, 2004 / Proposed Rules Constitutionally Protected Property from further environmental SUMMARY: We, the Fish and Wildlife Rights. documentation. This rule allows States Service (Service), announce a to require proof of liability insurance as reexamination of regulatory Civil Justice Reform a precondition for vessel numbering and mechanisms in relation to the 1998 This proposed rule meets applicable therefore concerns documentation of finding for a petition to list the Florida standards in sections 3(a) and 3(b)(2) of vessels. An ‘‘Environmental Analysis black bear (Ursus americanus Executive Order 12988, Civil Justice Check List’’ is available in the docket floridanus), under the Endangered Reform, to minimize litigation, where indicated under the ‘‘Public Species Act (ESA) of 1973, as amended. eliminate ambiguity, and reduce Participation and Request for Pursuant to a court order, we have burden. Comments’’ section of this preamble. reexamined only one factor, the Protection of Children Comments on this section will be inadequacy of existing regulatory considered before we make the final mechanisms in effect at the time of our We have analyzed this proposed rule decision on whether this rule should be previous 1998 12-month finding. under Executive Order 13045, categorically excluded from further DATES: The finding announced in this Protection of Children from environmental review. document was made on December 24, Environmental Health Risks and Safety 2003. Risks. This rule is not an economically List of Subjects in 33 CFR Part 174 ADDRESSES: The complete file for this significant rule and would not create an Marine safety, Reporting and environmental risk to health or risk to finding is available for public recordkeeping requirements. -

Origin of Tropical American Burrowing Reptiles by Transatlantic Rafting

Biol. Lett. in conjunction with head movements to widen their doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0531 burrows (Gans 1978). Published online Amphisbaenians (approx. 165 species) provide an Phylogeny ideal subject for biogeographic analysis because they are limbless (small front limbs are present in three species) and fossorial, presumably limiting dispersal, Origin of tropical American yet they are widely distributed on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean (Kearney 2003). Three of the five burrowing reptiles by extant families have restricted geographical ranges and contain only a single genus: the Rhineuridae (genus transatlantic rafting Rhineura, one species, Florida); the Bipedidae (genus Nicolas Vidal1,2,*, Anna Azvolinsky2, Bipes, three species, Baja California and mainland Corinne Cruaud3 and S. Blair Hedges2 Mexico); and the Blanidae (genus Blanus, four species, Mediterranean region; Kearney & Stuart 2004). 1De´partement Syste´matique et Evolution, UMR 7138, Syste´matique, Evolution, Adaptation, Case Postale 26, Muse´um National d’Histoire Species in the Trogonophidae (four genera and six Naturelle, 57 rue Cuvier, 75231 Paris Cedex 05, France species) are sand specialists found in the Middle East, 2Department of Biology, 208 Mueller Laboratory, Pennsylvania State North Africa and the island of Socotra, while the University, University Park, PA 16802-5301, USA largest and most diverse family, the Amphisbaenidae 3Centre national de se´quenc¸age, Genoscope, 2 rue Gaston-Cre´mieux, CP5706, 91057 Evry Cedex, France (approx. 150 species), is found on both sides of the *Author and address for correspondence: De´partment Syste´matique et Atlantic, in sub-Saharan Africa, South America and Evolution, UMR 7138, Syste´matique, Evolution, Adoptation, Case the Caribbean (Kearney & Stuart 2004). -

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History Database

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History database Abdala, C. S., A. S. Quinteros, and R. E. Espinoza. 2008. Two new species of Liolaemus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) from the puna of northwestern Argentina. Herpetologica 64:458-471. Abdala, C. S., D. Baldo, R. A. Juárez, and R. E. Espinoza. 2016. The first parthenogenetic pleurodont Iguanian: a new all-female Liolaemus (Squamata: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. Copeia 104:487-497. Abdala, C. S., J. C. Acosta, M. R. Cabrera, H. J. Villaviciencio, and J. Marinero. 2009. A new Andean Liolaemus of the L. montanus series (Squamata: Iguania: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. South American Journal of Herpetology 4:91-102. Abdala, C. S., J. L. Acosta, J. C. Acosta, B. B. Alvarez, F. Arias, L. J. Avila, . S. M. Zalba. 2012. Categorización del estado de conservación de las lagartijas y anfisbenas de la República Argentina. Cuadernos de Herpetologia 26 (Suppl. 1):215-248. Abell, A. J. 1999. Male-female spacing patterns in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Amphibia-Reptilia 20:185-194. Abts, M. L. 1987. Environment and variation in life history traits of the Chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus. Ecological Monographs 57:215-232. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfibios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2007. Anfibio y reptiles del Uruguay, 3rd edn. Montevideo, Uruguay: Serie Fauna 1. Ackermann, T. 2006. Schreibers Glatkopfleguan Leiocephalus schreibersii. Munich, Germany: Natur und Tier. Ackley, J. W., P. J. Muelleman, R. E. Carter, R. W. Henderson, and R. Powell. 2009. A rapid assessment of herpetofaunal diversity in variously altered habitats on Dominica. -

Snakes of the Everglades Agricultural Area1 Michelle L

CIR1462 Snakes of the Everglades Agricultural Area1 Michelle L. Casler, Elise V. Pearlstine, Frank J. Mazzotti, and Kenneth L. Krysko2 Background snakes are often escapees or are released deliberately and illegally by owners who can no longer care for them. Snakes are members of the vertebrate order Squamata However, there has been no documentation of these snakes (suborder Serpentes) and are most closely related to lizards breeding in the EAA (Tennant 1997). (suborder Sauria). All snakes are legless and have elongated trunks. They can be found in a variety of habitats and are able to climb trees; swim through streams, lakes, or oceans; Benefits of Snakes and move across sand or through leaf litter in a forest. Snakes are an important part of the environment and play Often secretive, they rely on scent rather than vision for a role in keeping the balance of nature. They aid in the social and predatory behaviors. A snake’s skull is highly control of rodents and invertebrates. Also, some snakes modified and has a great degree of flexibility, called cranial prey on other snakes. The Florida kingsnake (Lampropeltis kinesis, that allows it to swallow prey much larger than its getula floridana), for example, prefers snakes as prey and head. will even eat venomous species. Snakes also provide a food source for other animals such as birds and alligators. Of the 45 snake species (70 subspecies) that occur through- out Florida, 23 may be found in the Everglades Agricultural Snake Conservation Area (EAA). Of the 23, only four are venomous. The venomous species that may occur in the EAA are the coral Loss of habitat is the most significant problem facing many snake (Micrurus fulvius fulvius), Florida cottonmouth wildlife species in Florida, snakes included. -

Evolution of the Iguanine Lizards (Sauria, Iguanidae) As Determined by Osteological and Myological Characters

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1970-08-01 Evolution of the iguanine lizards (Sauria, Iguanidae) as determined by osteological and myological characters David F. Avery Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Life Sciences Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Avery, David F., "Evolution of the iguanine lizards (Sauria, Iguanidae) as determined by osteological and myological characters" (1970). Theses and Dissertations. 7618. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/7618 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. EVOLUTIONOF THE IGUA.NINELI'ZiUIDS (SAUR:U1., IGUANIDAE) .s.S DETEH.MTNEDBY OSTEOLOGICJJJAND MYOLOGIC.ALCHARA.C'l'Efi..S A Dissertation Presented to the Department of Zoology Brigham Yeung Uni ver·si ty Jn Pa.rtial Fillf.LLlment of the Eequ:Lr-ements fer the Dz~gree Doctor of Philosophy by David F. Avery August 197U This dissertation, by David F. Avery, is accepted in its present form by the Department of Zoology of Brigham Young University as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 30 l'/_70 ()k ate Typed by Kathleen R. Steed A CKNOWLEDGEHENTS I wish to extend my deepest gratitude to the members of m:r advisory committee, Dr. Wilmer W. Tanner> Dr. Harold J. Bissell, I)r. Glen Moore, and Dr. Joseph R. Murphy, for the, advice and guidance they gave during the course cf this study. -

Florida Department of Environmental Protection - Conservation Land Assessment Proposed Surplus Sites August 20, 2013

Florida Department of Environmental Protection - Conservation Land Assessment Proposed Surplus Sites August 20, 2013 State-Owned Acres Conservation Area Site Reference ID (GIS) County Section-Township-Range Allen David Broussard Catfish Creek Preserve State Park DRP-4 3.4 Polk County Section 018, Township 29-S, Range 29-E DRP-5 2.0 Polk County Section 018, Township 29-S, Range 29-E Anastasia State Park DRP-0 2.7 St. Johns County Section 021, Township 07-S, Range 30-E Atlantic Ridge Preserve State Park DRP-1 12.6 Martin County Section 34, Township 38-S, Range 42-E Avalon State Park DRP-2 2.2 St. Lucie County Section 03, Township 34-S, Range 40-E DRP-3 6.6 St. Lucie County Section 03, Township 34-S, Range 40-E Big Bend Wildlife Management Area FWC-BB 1 3.4 Dixie County Section 24, Township 10-S, Range 09-E FWC-BB 2 5.3 Dixie County Section 23, Township 10-S, Range 09-E Blackwater Heritage State Trail DRP-59 4.8 Santa Rosa County Section 010, Township 01-N, Range 28-W Blue Spring State Park FLMA_16 22.4 Volusia County Section 08, Township 18-S, Range 30-E Box-R Wildlife Management Area FWC-BX 1 26.0 Franklin County Section 021, Township 08-S, Range 08-W Bruner Bay Tract CF-836-25 43.9 Washington County Section 028, Township 03-S, Range 15-W Cayo Costa State Park DRP-10 0.2 Lee County Section 29, Township 44-S, Range 21-E DRP-11 0.1 Lee County Section 32, Township 44-S, Range 21-E DRP-12 0.2 Lee County Section 05, Township 45-S, Range 21-E DRP-13 0.4 Lee County Section 05, Township 45-S, Range 21-E DRP-14 0.2 Lee County Section 05, Township -

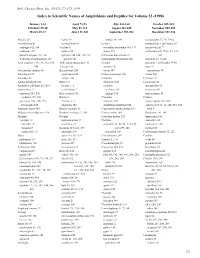

Index to Scientific Names of Amphibians and Reptiles for Volume 33 (1998)

Bull. Chicago Herp. Soc. 33(12):271-273, 1998 Index to Scientific Names of Amphibians and Reptiles for Volume 33 (1998) January 1-24 April 73-96 July 141-160 October 205-224 February 25-48 May 97-112 August 161-180 November 225-252 March 49-72 June 113-140 September 181-204 December 253-276 Abronia 20 slevini 19 fowleri 191-193 neotesselatus 75, 76, 79-82 Acanthodactylus steindachneri 19 Caiman neotesselatus × sexlineatus 82 bedriagai 182, 184 Apalone 91 crocodilus crocodilus 109, 177 septemvittatus 77 boskianus 185 mutica 148 yacare 177 sexlineatus 6-8, 75-81, 83, 144, dumerili exiguus 182, 185 spinifera 144-146, 239, 241 Callisaurus draconoides 52 146 erythrurus lineomaculatus 185 spinifera 40 Calloselasma rhodostoma 220 tesselatus 12, 75-84 Acris crepitans 143, 144, 152, 239, Arthrosaura synaptolepis 41 Cerastes tesselatus × sexlineatus 79-80 240 Atractus 250 cerastes 187 tigris 77 Acrochordus arafurae 68 Batrachoseps 220 vipera 187 marmoratus 78 Adelphicos 250 nigriventris 109 Cerberus rynchops 109 vanzoi 268 Afroedura 93 wrighti 109 Chalcides Coleonyx 20 Agama impalearis 183 Bipes 1-5 mionecton 185 Colostethus 92 Agalychnis callidryas 212-214 biporus 1, 2 ocellatus atopoglossus 92 Agkistrodon 32 canaliculatus 2 ocellatus 185 lacrimosus 92 contortrix 259, 260 Bitis caudalis 248 tiligugu 185 tamacuarensis 41 mokasen 189, 190 Blanus 2 Chameleo Coluber piscivorus 250, 258, 259 cinereus 2, 3 africanus 184 algirus algirus 182, 186 leucostoma 100 tingitanus 183 chameleon chameleon 184 constrictor 9-10, 12, 148, 239, 241 Aipysurus laevis -

Studies on Amphisbaenids

STUDIES ON AMPHISBAENIDS (AMPHISBAENJA, REPTILIA) 1. A TAXONOMIC REVISION OF THE TROGONOPHINAE, AND A FUNC- TIONAL INTERPRETATION OF THE AMPHISBAENID ADAPTIVE PATTERN CARL GANS BULLETIN OF THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY VOLUME 119 : ARTICLE 3 NEW YORK: 1960 STUDIES ON AMPHISBAENIDS (AMPHISBAENIA, REPTILIA) STUDIES ON AMPHISBAENIDS (AMPHISBAENIA, REPTILIA) 1. A TAXONOMIC REVISION OF THE TROGONOPHINAE, AND A FUNCTIONAL INTERPRETATION OF THE AMPHIS- BAENID ADAPTIVE PATTERN CARL GANS Research Associate, Department of Amphibians and Reptiles The American Museum of Natural History Department of Biology, The University of Buffalo Buffalo, New York Carnegie Museum, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania BULLETIN OF THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY VOLUME 119 : ARTICLE 3 NEW YORK 1960 BULLETIN OF THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY Volume 119, article 3, pages 129-204, text figures 1-32, plate 45, tables 1-3 Issued May 23, 1960 Price: $1.50 a copy CONTENTS INTRODUCTION. * * * 4 135 A TAXONOMIC REVISION OF THE TROGONOPHINAE * . * * * * * 136 Material. * . * * * - 136 Discussion of Characters. * . * * * * 139 Shape and Scutellation of Head. * . X 139 Diplometopon. * . * . - 139 Other Acrodont Forms. * * * * 141 Posterior Integument ............. * . * * . * . 141 Diplometopon. ****** * . o* * * * * 141 Other Acrodont Forms. * * * * 144 Color Pattern ................ * * * * * * . * . 146 Skull. *. s* * * * * 147 General Comparison ............ * * * * * . * @ 147 Trogonophis. * . * * * * 149 Pachycalamus. * . * . e 153 *****. *- * * * - Diplometopon.