The Scientific Role of Malcolm Clarke in the Azores

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Natural History of the Squid

1. Natural History of the Squid INTRODUCTION Cephalopods in general and squid in particular have been the subject of con- siderable curiosity everywhere that man has become acquainted with the sea. These fast-moving animals possess a number of features usually associated only with verte- brate forms and to practitioners of anthropomorphism they appear to have con- siderable cunning. Popular accounts of these animals are recurrent and only a few wil be mentioned to introduce the subject: Lane (1957) provided a comprehensive and readable coverage of cephalopods in a book slanted toward Octopus; Morton's (1958) introduction to mollusks sets the cephalopods among other members of the phylum; some invertebrate zoology tests, especially one by Russell-Hunter (1968), give good coverage of cephalopods; excellent photographic coverage can be found in articles by Voss and Sisson (1967 and 1971); and behavioral aspects of cephal- opods are summarized in a concise book by Wells (1962). Systematic position Cephalopods are relatively large, active, predaceous mollusks with a high level of nervous development. There are approximately 400 living species which are distributed throughout all marine environments. Fossils of shelled cephalopods are well known and abundant in the Paleozoic and Mesozoic; their direct descendants are almost entirely extinct today, having been replaced by shell-less cephalopods which did not leave a fossil record. Modern forms are subdivided into the Nautiloi- dea (including only the relict genus Nautilus) and the Coleoidea, encompassing the remaining dibranchiate species. The latter are composed of eight-armed forms (Octopoda) and ten-armed forms (Decapoda) which include the true squids (Teu- thoidea) and cuttlefishes (Sepioidea). -

The Role of Malcolm Clarke (1930–2013) in the Azores As a Scientist and Educationist J.N

Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 2017, 97(4), 821–828. # Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 2014 doi:10.1017/S0025315414000794 The role of Malcolm Clarke (1930–2013) in the Azores as a scientist and educationist j.n. gomes-pereira1,2, r. prieto1, v. neves1, j. xavier3, c. pham1, j. gonc‚alves1, f. porteiro1, r. santos1 and h. martins1 1University of the Azores, LARSyS Associated Laboratory, IMAR and Department of Oceanography and Fisheries, 2Portuguese Task Group for the Extension of the Continental Shelf (EMEPC), Rua Costa Pinto 165, 2770-047 Pac¸o de Arcos, Portugal, 3Institute of Marine Research (IMAR-CMA), Department of Zoology, University of Coimbra, 3004-517 Coimbra, Portugal and British Antarctic Survey, Natural Environment Research Council, High Cross, Madingley Road, CB3 0ET Cambridge, USA Malcolm Roy Clarke (1930–2013) was a British teuthologist who made an important contribution to marine science in the Azores archipelago (Portugal). Malcolm started doing research in the Azores from 1980s onward, settling for residency in 2000 after retirement (in 1987). He kept publishing on Azorean cephalopods collaborating in 20% of the peer reviewed works focus- ing on two main areas: dietary studies; and the ecology of cephalopods on seamounts. Since his first visit in 1981, he was involved in the description of the dietary ecology of several cetaceans, seabirds, and large pelagic and deep-water fish. Using his own data, Malcolm revised the association of cephalopods with seamounts, updating and enlarging the different cephalopod groups according to species behaviour and ecology. Malcolm taught several students working in the Azores on cephalopods and beak identification, lecturing the Third International Workshop in Faial (2007). -

AOU Classification Committee – North and Middle America

AOU Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2016-C No. Page Title 01 02 Change the English name of Alauda arvensis to Eurasian Skylark 02 06 Recognize Lilian’s Meadowlark Sturnella lilianae as a separate species from S. magna 03 20 Change the English name of Euplectes franciscanus to Northern Red Bishop 04 25 Transfer Sandhill Crane Grus canadensis to Antigone 05 29 Add Rufous-necked Wood-Rail Aramides axillaris to the U.S. list 06 31 Revise our higher-level linear sequence as follows: (a) Move Strigiformes to precede Trogoniformes; (b) Move Accipitriformes to precede Strigiformes; (c) Move Gaviiformes to precede Procellariiformes; (d) Move Eurypygiformes and Phaethontiformes to precede Gaviiformes; (e) Reverse the linear sequence of Podicipediformes and Phoenicopteriformes; (f) Move Pterocliformes and Columbiformes to follow Podicipediformes; (g) Move Cuculiformes, Caprimulgiformes, and Apodiformes to follow Columbiformes; and (h) Move Charadriiformes and Gruiformes to precede Eurypygiformes 07 45 Transfer Neocrex to Mustelirallus 08 48 (a) Split Ardenna from Puffinus, and (b) Revise the linear sequence of species of Ardenna 09 51 Separate Cathartiformes from Accipitriformes 10 58 Recognize Colibri cyanotus as a separate species from C. thalassinus 11 61 Change the English name “Brush-Finch” to “Brushfinch” 12 62 Change the English name of Ramphastos ambiguus 13 63 Split Plain Wren Cantorchilus modestus into three species 14 71 Recognize the genus Cercomacroides (Thamnophilidae) 15 74 Split Oceanodroma cheimomnestes and O. socorroensis from Leach’s Storm- Petrel O. leucorhoa 2016-C-1 N&MA Classification Committee p. 453 Change the English name of Alauda arvensis to Eurasian Skylark There are a dizzying number of larks (Alaudidae) worldwide and a first-time visitor to Africa or Mongolia might confront 10 or more species across several genera. -

Classic Versus Metabarcoding Approaches for the Diet Study of a Remote Island Endemic Gecko

Questioning the proverb `more haste, less speed': classic versus metabarcoding approaches for the diet study of a remote island endemic gecko Vanessa Gil1,*, Catarina J. Pinho2,3,*, Carlos A.S. Aguiar1, Carolina Jardim4, Rui Rebelo1 and Raquel Vasconcelos2 1 Centre for Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Changes, Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal 2 CIBIO, Centro de Investigacão¸ em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, InBIO Laboratório Associado, Universidade do Porto, Vairão, Portugal 3 Departamento de Biologia, Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal 4 Instituto das Florestas e Conservacão¸ da Natureza IP-RAM, Funchal, Madeira, Portugal * These authors contributed equally to this work. ABSTRACT Dietary studies can reveal valuable information on how species exploit their habitats and are of particular importance for insular endemics conservation as these species present higher risk of extinction. Reptiles are often neglected in island systems, principally the ones inhabiting remote areas, therefore little is known on their ecological networks. The Selvagens gecko Tarentola (boettgeri) bischoffi, endemic to the remote and integral reserve of Selvagens Archipelago, is classified as Vulnerable by the Portuguese Red Data Book. Little is known about this gecko's ecology and dietary habits, but it is assumed to be exclusively insectivorous. The diet of the continental Tarentola species was already studied using classical methods. Only two studies have used next-generation sequencing (NGS) techniques for this genus thus far, and very few NGS studies have been employed for reptiles in general. Considering the lack of information on its diet Submitted 10 April 2019 and the conservation interest of the Selvagens gecko, we used morphological and Accepted 22 October 2019 Published 2 January 2020 DNA metabarcoding approaches to characterize its diet. -

United States National Museum Bulletin 291

SYSTEMATICS AND ZOOGEOGRAPHY OF THE WORLDWIDE BATHYPELAGIC SQUID BATHYTEUTHIS (CEPHALOPODA: OEGOPSIDA) For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $1.50 (paper covers) UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM BULLETIN 291 Systematics and Zoogeography of the Worldwide Bathypelagic Squid Bathyteuthis (Cephalopoda: Oegopsida) CLYDE F. E. ROPER Division of Mollusks Smithsonian Institution SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION PRESS CITY OF WASHINGTON • 1969 Publications of the United States National Museum The scientific publications of the United States National Museum include two series, Proceedings of the United States Nationcd Museum and United States National Museum Bulletin. In these series are published original articles and monographs deal- ing with the collections and work of the Museum and setting forth newly acquired facts in the field of anthropology, biology, geology, history, and technology. Copies of each publication are distributed to libraries and scientific organizations and to specialists and others in- terested in the various subjects. The Prooeedings^f begun in 1878, are intended for the publication, in separate form, of shorter papers. These are gathered in volumes, oc- tavo in size, with the publication date of each paper recorded in the table of contents of the volume. In the Bulletin series, the first of which was issued in 1875, appear longer, separate publications consisting of monographs (occasionally in several parts) and volumes in w^iich are collected works on related subjects. Bulletins are either octavo or quarto in size, depending on the needs of the presentation. Since 1902, papers relating to the bo- tanical collections of the Museum have been published in the Bulletin series under the heading Contributions from the. -

Proposals 2018-C

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2018-C 1 March 2018 No. Page Title 01 02 Adopt (a) a revised linear sequence and (b) a subfamily classification for the Accipitridae 02 10 Split Yellow Warbler (Setophaga petechia) into two species 03 25 Revise the classification and linear sequence of the Tyrannoidea (with amendment) 04 39 Split Cory's Shearwater (Calonectris diomedea) into two species 05 42 Split Puffinus boydi from Audubon’s Shearwater P. lherminieri 06 48 (a) Split extralimital Gracula indica from Hill Myna G. religiosa and (b) move G. religiosa from the main list to Appendix 1 07 51 Split Melozone occipitalis from White-eared Ground-Sparrow M. leucotis 08 61 Split White-collared Seedeater (Sporophila torqueola) into two species (with amendment) 09 72 Lump Taiga Bean-Goose Anser fabalis and Tundra Bean-Goose A. serrirostris 10 78 Recognize Mexican Duck Anas diazi as a species 11 87 Transfer Loxigilla portoricensis and L. violacea to Melopyrrha 12 90 Split Gray Nightjar Caprimulgus indicus into three species, recognizing (a) C. jotaka and (b) C. phalaena 13 93 Split Barn Owl (Tyto alba) into three species 14 99 Split LeConte’s Thrasher (Toxostoma lecontei) into two species 15 105 Revise generic assignments of New World “grassland” sparrows 1 2018-C-1 N&MA Classification Committee pp. 87-105 Adopt (a) a revised linear sequence and (b) a subfamily classification for the Accipitridae Background: Our current linear sequence of the Accipitridae, which places all the kites at the beginning, followed by the harpy and sea eagles, accipiters and harriers, buteonines, and finally the booted eagles, follows the revised Peters classification of the group (Stresemann and Amadon 1979). -

Bulletin of the United States Fish Commission

A REVIEW OF THE CEPHALOPODS OF WESTERN NORTH AMERICA By S. Stillman Berry Stanford University, California Blank page retained for pagination A REVIEW OF THE CEPHALOPODS OF WESTERN NORTH AMERICA. By S. STILLMAN BERRY, Stanford University, California. J1. INTRODUCTION. "The region covered by the present report embraces the western shores of North America between Bering Strait on the north and the Coronado Islands on the south, together with the immediately adjacent waters of Bering Sea and the North Pacific Ocean. No attempt is made to present a monograph nor even a complete catalogue of the species now living within this area. The material now at hand is inadequate to properly repre sent the fauna of such a vast region, and the stations at which anything resembling extensive collecting has been done are far too few and scattered. Rather I have merely endeavored to bring out of chaos and present under one cover a resume of such work as has already been done, making the necessary corrections wherever possible, and adding accounts of such novelties as have been brought to my notice. Descriptions are given of all the species known to occur or reported from within our limits, and these have been made. as full and accurate as the facilities available to me would allow. I have hoped to do this in such a way that students, particularly in the Western States, will find it unnecessary to have continual access to the widely scattered and often unavailable literature on the subject. In a number of cases, however, the attitude adopted must be understood as little more than provisional in its nature, and more or less extensive revision is to be expected later, especially in the case of the large and difficult genus Polypus, which here attains a development scarcely to be sur passed anywhere. -

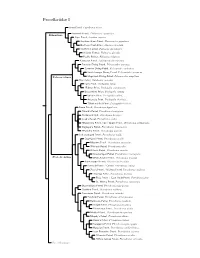

Procellariidae Species Tree

Procellariidae I Snow Petrel, Pagodroma nivea Antarctic Petrel, Thalassoica antarctica Fulmarinae Cape Petrel, Daption capense Southern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes giganteus Northern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes halli Southern Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialoides Atlantic Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialis Pacific Fulmar, Fulmarus rodgersii Kerguelen Petrel, Aphrodroma brevirostris Peruvian Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides garnotii Common Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides urinatrix South Georgia Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides georgicus Pelecanoidinae Magellanic Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides magellani Blue Petrel, Halobaena caerulea Fairy Prion, Pachyptila turtur ?Fulmar Prion, Pachyptila crassirostris Broad-billed Prion, Pachyptila vittata Salvin’s Prion, Pachyptila salvini Antarctic Prion, Pachyptila desolata ?Slender-billed Prion, Pachyptila belcheri Bonin Petrel, Pterodroma hypoleuca ?Gould’s Petrel, Pterodroma leucoptera ?Collared Petrel, Pterodroma brevipes Cook’s Petrel, Pterodroma cookii ?Masatierra Petrel / De Filippi’s Petrel, Pterodroma defilippiana Stejneger’s Petrel, Pterodroma longirostris ?Pycroft’s Petrel, Pterodroma pycrofti Soft-plumaged Petrel, Pterodroma mollis Gray-faced Petrel, Pterodroma gouldi Magenta Petrel, Pterodroma magentae ?Phoenix Petrel, Pterodroma alba Atlantic Petrel, Pterodroma incerta Great-winged Petrel, Pterodroma macroptera Pterodrominae White-headed Petrel, Pterodroma lessonii Black-capped Petrel, Pterodroma hasitata Bermuda Petrel / Cahow, Pterodroma cahow Zino’s Petrel / Madeira Petrel, Pterodroma madeira Desertas Petrel, Pterodroma -

Shearwatersrefs V1.10.Pdf

Introduction I have endeavoured to keep typos, errors, omissions etc in this list to a minimum, however when you find more I would be grateful if you could mail the details during 2018 & 2019 to: [email protected]. Please note that this and other Reference Lists I have compiled are not exhaustive and are best employed in conjunction with other sources. Grateful thanks to Ashley Fisher (www.scillypelagics.com) for the cover images. All images © the photographer. Joe Hobbs Index The general order of species follows the International Ornithologists' Union World Bird List (Gill, F. & Donsker, D. (eds.) 2017. IOC World Bird List. Available from: http://www.worldbirdnames.org/ [version 7.3 accessed August 2017]). Version Version 1.10 (January 2018). Cover Main image: Great Shearwater. At sea 3’ SW of the Bishop Rock, Isles of Scilly. 8th August 2009. Picture by Ashley Fisher. Vignette: Sooty Shearwater. At sea off the Isles of Scilly. 14th August 2009. Picture by Ashley Fisher. Species Page No. Audubon's Shearwater [Puffinus lherminieri] 34 Balearic Shearwater [Puffinus mauretanicus] 28 Bannerman's Shearwater [Puffinus bannermani] 37 Barolo Shearwater [Puffinus baroli] 38 Black-vented Shearwater [Puffinus opisthomelas] 30 Boyd's Shearwater [Puffinus boydi] 38 Bryan's Shearwater [Puffinus bryani] 29 Buller's Shearwater [Ardenna bulleri] 15 Cape Verde Shearwater [Calonectris edwardsii] 12 Christmas Island Shearwater [Puffinus nativitatis] 23 Cory's Shearwater [Calonectris borealis] 9 Flesh-footed Shearwater [Ardenna carneipes] 21 Fluttering -

A Checklist of Birds of Britain (9Th Edition)

Ibis (2018), 160, 190–240 doi: 10.1111/ibi.12536 The British List: A Checklist of Birds of Britain (9th edition) CHRISTOPHER J. MCINERNY,1,2 ANDREW J. MUSGROVE,1,3 ANDREW STODDART,1 ANDREW H. J. HARROP1 † STEVE P. DUDLEY1,* & THE BRITISH ORNITHOLOGISTS’ UNION RECORDS COMMITTEE (BOURC) 1British Ornithologists’ Union, PO Box 417, Peterborough PE7 3FX, UK 2School of Life Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK 3British Trust for Ornithology, The Nunnery, Thetford, IP24 2PU, UK Recommended citation: British Ornithologists’ Union (BOU). 2018. The British List: a Checklist of Birds of Britain (9th edition). Ibis 160: 190–240. and the Irish Rare Birds Committee are no longer INTRODUCTION published within BOURC reports. This, the 9th edition of the Checklist of the Birds The British List is under continuous revision by of Britain, referred to throughout as the British BOURC. New species and subspecies are either List, has been prepared as a statement of the status added or removed, following assessment; these are of those species and subspecies known to have updated on the BOU website (https://www.bou. occurred in Britain and its coastal waters (Fig. 1). org.uk/british-list/recent-announcements/) at the time It incorporates all the changes to the British List of the change, but only come into effect on the List up to and including the 48th Report of the British on publication in a BOURC report in Ibis. A list of Ornithologists’ Union Records Committee the species and subspecies removed from the British (BOURC) (BOU 2018), and detailed in BOURC List since the 8th edition is shown in Appendix 1. -

Grace Knowledge

acarology - study of mites ✸ aceology - therapeutics ✸ acology - study of medical remedies ✸ acoustics - science of sound ✸ adenology - study of glands ✸ aedoeology - science of generative organs ✸ aerobiology - study of airborne organisms ✸ aerodonetics - science or study of gliding ✸ aerodynamics - dynamics of gases; science of movement in a flow of air or gas ✸ aerolithology - study of aerolites; meteorites ✸ aerology - study of the atmosphere ✸ aeronautics - study of navigation through air or space ✸ aerophilately - collecting of air -mail stamps ✸ aerostatics - science of air pressure; art of ballooning ✸ agonistics - art and theory of prize -fighting ✸ agriology - the comparative study of primitive peoples ✸ agrobiology - study of plant nutrition; soil yields ✸ agrology - study of agricultural soils ✸ agronomics - study of productivity of land ✸ agrostology - science or study of grasses ✸ alethiology - study of truth ✸ algedonics - science of pleasure and pain ✸ algology - study of algae ✸ anaesthesiology - study of anaesthetics ✸ anaglyptics - art of carving in bas -relief ✸ anagraphy - art of constructing catalogues ✸ anatomy - study of the structure of the body ✸ andragogy - science of teaching adults ✸ anemology - study of winds ✸ angelology - study of angels ✸ angiology - study of blood flow and lymphatic system ✸ anthropobiology - study of human biology ✸ anthropology - study of human cultures ✸ aphnology - science of wealth ✸ apiology - study of bees ✸ arachnology - study of spiders ✸ archaeology - study of human material remains -

Minisode: All of My Secret Travel Trips + Some Updates Ologies Podcast April 30, 2019

Minisode: All of My Secret Travel Trips + Some Updates Ologies Podcast April 30, 2019 Oh heeey, it’s a dog in a Baby Bjorn, Alie Ward, back with a little, tiny, mini episode of Ologies. Okay, listen. Many of you on Patreon were like, “Dad, take a week off for the sake of all that is disheveled and smelly.” And if you are on Patreon.com/Ologies, you’ve seen like, I think, 11 posts this week titled, “Call for questions,” in which I ask you to submit questions for the guests. Because I’ve been in the Midwest seeing Kansas, Nebraska, Iowa. I saw both Dakotas, and one Minnesota, and a Wisconsin. I’ve been doing interviews with ologists who’ve been on my lists for like, literal years. I finally, finally made the trek out. So many interviews in a week that I’ve literally lost my voice. So, with so many miles, and a bunch of delayed flights, and an April snowstorm, I was just going to take a week off since I’m harvesting so many future episodes for all of our brain areas and I’ve had no time not being on the road or doing interviews. But then I thought, “Spring’s here. Summer’s coming. I travel so very much. Perhaps I should go into my rental car parked here on a side street of metropolitan Minneapolis and just record a quick episode, like a weirdo talking into a microphone in full daylight – [whispers] So far no one’s looking at me. – to record a quick episode of travel tips from someone who cannot remember what the inside of her own house looks like.