Redalyc.Gender, Space and Place: the Experience of Servants In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Short History of Colchester Castle

Colchester Borough Council Colchester and Ipswich Museum Service A SHORT HISTORY OF COLCHESTER CASTLE 1066, the defeat of the English by the invading army of Duke William of Normandy. After his victory at the Battle of Hastings, William strengthened his hold on the defeated English by ordering castles to be built throughout the country. Colchester was chosen for its port and its important military position controlling the southern access to East Anglia. In 1076 work began on Colchester Castle, the first royal stone castle to be built by William in England. The castle was built around the ruins of the colossal Temple of Claudius using the Roman temple vaults as its base, parts of which can be seen to this day. As a result the castle is the largest ever built by the Normans. It was constructed mainly of building material from Colchester's Roman ruins with some imported stone. Most of the red brick in the castle was taken from Roman buildings. England, William's newly won possession, was soon under threat from another invader, King Cnut of Denmark. The castle had only been built to first floor level when it had to be hastily strengthened with battlements. The invasion never came and work resumed on the castle which was finally completed to three or four storeys in 1125. The castle came under attack in 1216 when it was besieged for three months and eventually captured by King John after he broke his agreement with the rebellious nobles (Magna Carta). By 1350, however, its military importance had declined and the building was mainly used as a prison. -

Lamarsh Village Hall Magazine Contact Bret & Rosemary Johnson 227988

Look Out The Parish Magazine for Alphamstone, Lamarsh, Great & Little Henny Middleton, Twinstead and Wickham St Pauls May 2020 www.northhinckfordparishes.org.uk WHO TO CONTACT Team Rector: Revd. Margaret H. King [email protected] 269385 mobile - 07989 659073 Usual day off Friday Team Vicar: Revd. Gill Morgan [email protected] 584993 Usual day off Wednesday Team Curate: Revd. Paul Grover [email protected] 269223 Team Administrator: Fiona Slot [email protected] (working hours 9:00 am - 12 noon Monday, Tuesday and Thursday). 278123 Reader: Mr. Graham King 269385 The Church of St Barnabas, Alphamstone Churchwardens: Desmond Bridge 269224 Susan Langan 269482 Magazine Contact: Melinda Varcoe 269570 [email protected] The Church of St Mary the Virgin, Great & Little Henny Churchwarden: Jeremy Milbank 269720 Magazine Contact: Stella Bixley 269317 [email protected] The Church of the Holy Innocents, Lamarsh Churchwarden: Andrew Marsden 227054 Magazine Contact: Bret & Rosemary 227988 [email protected] Johnson The Church of All Saints, Middleton Churchwarden: Sue North 370558 Magazine Contact: Jude Johnson 582559 [email protected] The Church of St John the Evangelist, Twinstead Churchwardens: Elizabeth Flower 269898 Henrietta Drake 269083 Magazine Contact: Cathy Redgrove 269097 [email protected] The Church of All Saints, Wickham St. Pauls Churchwarden: Janice Rudd 269789 Magazine Contact: Susannah Goodbody 269250 [email protected] www.northhinckfordparishes.org.uk Follow us on facebook : www.facebook.com/northhinckfordparishes Magazine Editor: Magazine Advertising: Annie Broderick 01787 269152 Anthony Lyster 0800 0469 069 1 Broad Cottages, Broad Road The Coach House Wickham St Pauls Ashford Lodge Halstead. -

Essex County Council (The Commons Registration Authority) Index of Register for Deposits Made Under S31(6) Highways Act 1980

Essex County Council (The Commons Registration Authority) Index of Register for Deposits made under s31(6) Highways Act 1980 and s15A(1) Commons Act 2006 For all enquiries about the contents of the Register please contact the: Public Rights of Way and Highway Records Manager email address: [email protected] Telephone No. 0345 603 7631 Highway Highway Commons Declaration Link to Unique Ref OS GRID Statement Statement Deeds Reg No. DISTRICT PARISH LAND DESCRIPTION POST CODES DEPOSITOR/LANDOWNER DEPOSIT DATE Expiry Date SUBMITTED REMARKS No. REFERENCES Deposit Date Deposit Date DEPOSIT (PART B) (PART D) (PART C) >Land to the west side of Canfield Road, Takeley, Bishops Christopher James Harold Philpot of Stortford TL566209, C/PW To be CM22 6QA, CM22 Boyton Hall Farmhouse, Boyton CA16 Form & 1252 Uttlesford Takeley >Land on the west side of Canfield Road, Takeley, Bishops TL564205, 11/11/2020 11/11/2020 allocated. 6TG, CM22 6ST Cross, Chelmsford, Essex, CM1 4LN Plan Stortford TL567205 on behalf of Takeley Farming LLP >Land on east side of Station Road, Takeley, Bishops Stortford >Land at Newland Fann, Roxwell, Chelmsford >Boyton Hall Fa1m, Roxwell, CM1 4LN >Mashbury Church, Mashbury TL647127, >Part ofChignal Hall and Brittons Farm, Chignal St James, TL642122, Chelmsford TL640115, >Part of Boyton Hall Faim and Newland Hall Fann, Roxwell TL638110, >Leys House, Boyton Cross, Roxwell, Chelmsford, CM I 4LP TL633100, Christopher James Harold Philpot of >4 Hill Farm Cottages, Bishops Stortford Road, Roxwell, CMI 4LJ TL626098, Roxwell, Boyton Hall Farmhouse, Boyton C/PW To be >10 to 12 (inclusive) Boyton Hall Lane, Roxwell, CM1 4LW TL647107, CM1 4LN, CM1 4LP, CA16 Form & 1251 Chelmsford Mashbury, Cross, Chelmsford, Essex, CM14 11/11/2020 11/11/2020 allocated. -

A Guide to Your Council Tax

2019 2020 A GUIDE TO YOUR COUNCIL TAX WE WANT TO PROTECT YOUR VOTE TOTO VOTEVOTE ATAT AA POLLINGPOLLING Contents STATIONSTATION DON’TDON’T FORGETFORGET 4 How your Council Tax is shared 6 £100 million investment plan TOTO BRINGBRING YOURYOUR IDID 9 Your guide to Council Tax 13 Easy ways to pay WHAT DOES THIS 14 Braintree street market VOTER ID MEAN FOR ME? BRAINTREE DISTRICT 16 Handy contacts COUNCIL HAS BEEN This means that when you go to vote at a polling station in the Braintree SELECTED BY THE CABINET District, before you are given your OFFICE TO TAKE PART ballot paper you will be asked to show IN THE 2019 ELECTORAL either: INTEGRITY TRIALS FOR • one piece of photo ID or • two pieces of non-photo ID, THE LOCAL ELECTIONS one of which must show your ON 2 MAY. current address. Contact us There’ll be no change to postal voting. The trial will provide insight into WEBSITE: how best to ensure the security of The most common photo ID types www.braintree.gov.uk the voting process and reduce are likely to be passport, driving the risk of voter fraud. licence or bus pass, and common EMAIL: non-photo ID types are things like [email protected] Electoral fraud undermines your poll card, Council Tax bill or democracy and takes away a bank card. We’ve listed the current TELEPHONE: person’s right to vote as they accepted ID types on the separate 01376 552525 would like. The Voter ID trial will VOTER ID leaflet. The lists may be focus specifically on voter fraud at POST: subject to change, however final polling stations, where an individual details of the ID types required will Braintree District Council, pretends to be someone else known be on your poll card letter which all Causeway House, as “personation”. -

Special Qualities of the Dedham Vale AONB Evaluation of Area Between Bures and Sudbury

Special Qualities of the Dedham Vale AONB Evaluation of Area Between Bures and Sudbury Final Report July 2016 Alison Farmer Associates 29 Montague Road Cambridge CB4 1BU 01223 461444 [email protected] In association with Julie Martin Associates and Countryscape 2 Contents 1: Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Appointment............................................................................................................ 3 1.2 Background and Scope of Work.............................................................................. 3 1.3 Natural England Guidance on Assessing Landscapes for Designation ................... 5 1.4 Methodology and Approach to the Review .............................................................. 6 1.5 Format of Report ..................................................................................................... 7 2: The Evaluation Area ...................................................................................................... 8 2.1 Landscape Character Assessments as a Framework ............................................. 8 2.2 Defining and Reviewing the Evaluation Area Extent ................................................ 9 3: Designation History ..................................................................................................... 10 3.1 References to the Wider Stour Valley in the Designation of the AONB ................. 10 3.2 Countryside Commission Designation -

Draft Recommendations on the Future Electoral Arrangements for Essex County Council

Draft recommendations on the future electoral arrangements for Essex County Council August 2003 © Crown Copyright 2003 Applications for reproduction should be made to: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Copyright Unit. The mapping in this report is reproduced from OS mapping by The Electoral Commission with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD 03114G. This report is printed on recycled paper. 2 Contents page What is The Boundary Committee for England? 5 Summary 7 1 Introduction 17 2 Current electoral arrangements 21 3 Submissions received 25 4 Analysis and draft recommendations 27 5 What happens next? 57 Appendices A Draft recommendations for Essex County Council: detailed mapping 59 B Code of practice on written consultation 61 3 4 What is The Boundary Committee for England? The Boundary Committee for England is a committee of The Electoral Commission, an independent body set up by Parliament under the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000. The functions of the Local Government Commission for England were transferred to The Electoral Commission and its Boundary Committee on 1 April 2002 by the Local Government Commission for England (Transfer of Functions) Order 2001 (SI 2001 No. 3692). The Order also transferred to The Electoral Commission the functions of the Secretary of State in relation to taking decisions on recommendations for changes to local authority electoral arrangements and implementing them. Members of the Committee: Pamela Gordon (Chair) Professor Michael Clarke CBE Robin Gray Joan Jones CBE Anne M. -

A4 Simple Report 1-Col No Divider Nov 2019

Issue number: BT-JAC-020631 550-0003-EIA Bramford to Twinstead Scoping Report: Volume 2: Appendices May 2021 Page left intentionally blank National Grid | May 2021 | Bramford to Twinstead i Contents Contents ii Appendix 1.1 Transboundary Supporting Information 2 Appendix 2.1 Relevant Environmental Legislation, Policy and Guidance 6 Appendix 2.2 Local Planning Policy 23 Appendix 4.1 Outline Code of Construction Practice 31 Appendix 6.1 Key Characteristics of Landscape Character Assessment 44 Appendix 6.2 Landscape Assessment Methodology 51 Appendix 6.3 Visual Assessment Methodology 72 Appendix 6.4 Wireline and Photomontage Methodology 81 Appendix 6.5 Arboricultural Survey Methodology 87 Appendix 7.1 Biodiversity Supporting Information 91 Appendix 7.2 Ecology Survey Methodology 103 Appendix 7.3 Draft Habitats Regulations Assessment Screening Report 128 Appendix 17.1 Major Accidents and Disasters Scoping Table 144 Appendix 18.1 Cumulative Effects Assessment Long List Table 153 National Grid | May 2021 | Bramford to Twinstead ii Appendix 1.1 Transboundary Supporting Information National Grid | May 2021 | Bramford to Twinstead iii Page left intentionally blank National Grid | May 2021 | Bramford to Twinstead 1 Appendix 1.1 Transboundary Supporting Information Criteria and Relevant Considerations Result of the Screening Considerations Characteristics of the development: The Bramford to Twinstead project is a proposal to Size of the development consent and build a new c.27km 400kV electricity reinforcement and associated infrastructure between Use of natural resources Bramford in Suffolk and Twinstead in Essex. It includes Production of waste the removal of the existing 132kV overhead line Pollution and nuisances between Burstall Bridge and Twinstead Tee, and a new Risk of accidents substation at Butler’s Wood. -

Essex County Fire & Rescue Service

Essex County Fire & Rescue Service Our Values: Respect, Accountability, Openness and Involvement Strategic Risk Assessment of the Medium to Longer-Term Service Operating Environment 2009 – 2010 2 Countywide Review 2009 Contents 1. Foreword .......................................................................................................................................4 2. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................5 3. Executive Summary .................................................................................................................6 4. Climate Change in East of England ................................................................................10 5. Demographics of Essex ......................................................................................................22 6. Diversity .......................................................................................................................................26 7. Older People in Essex ...........................................................................................................32 8. County Development and Transport Infrastructure ...............................................40 9. The Changing Face of Technology ................................................................................57 10. Terrorism .....................................................................................................................................62 -

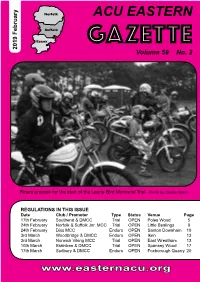

View Febuary 2019 Issue

Norfolk ACU EASTERN Suffolk Essex 2019 February Volume 59 No. 2 Riders prepare for the start of the Laurie Bird Memorial Trial - Photo by Charlie Mann REGULATIONS IN THIS ISSUE Date Club / Promoter Type Status Venue Page 17th February Southend & DMCC Trial OPEN Poles Wood 5 24th February Norfolk & Suffolk Jnr. MCC Trial OPEN Little Bealings 9 24th February Diss MCC Enduro OPEN Santon Downham 10 3rd March Woodbridge & DMCC Enduro OPEN Iken 13 3rd March Norwich Viking MCC Trial OPEN East Wreatham 13 10th March Braintree & DMCC Trial OPEN Spansey Wood 17 17th March Sudbury & DMCC Enduro OPEN Foxborough Quarry 20 www.easternacu.org 2018 OFFICIALS OF ACU EASTERN President: Alan Penny ’Culross’, Hadleigh Road, Elmsett, Ipswich, Suffolk, IP7 6ND Tel: 01473 658768 e-mail: [email protected] Life Vice Presidents: Dennis Slaughter MBE, Albert Brace Honorary Life Vice Presidents: Roy Bannister Vice Presidents: Roy Bannister Roger Chaplin Alan Foskew Geoff Brace Sidge Kenny Vera Hearn Margaret Mellish Chairman: (R.G) Jack Hearn 25, Quinton Road, Needham Market, Suffolk, IP6 8BP Tel: 01449 721042 Mob: 07774 801205 e-mail: [email protected] Vice Chairmen: Alan Foskew 9 Ebeneezer Close, Witham, Essex, CM8 2HX Tel: 01376 517169 e-mail: [email protected] Geoff Brace 15 Ozier Court, Safron Walden, Essex, CB11 4BH Tel.: 01799 520336 e-mail: [email protected] Treasurer: Andrew Hay 27, Tizzick Close, Three Score, Norwich.NR5 9HB. Tel: 01603 734700 e-mail: [email protected] Centre Secretary: Lyn Berwick 23, Tymmes Place, Hasketon, Ipswich, Suffolk , IP13 6JD Tel: 07857 601753 Mob: 07857 601753 e-mail: [email protected] Life Honorary Member of the Eastern Centre ACU: Mrs. -

Bures Hamlet Housing Needs Statistics 2021

www.braintree.gov.uk/housing/housing-statnav Key Housing Needs Statistics Bures Hamlet Snapshot: January 2021 To be read in conjunction with the ‘Guide to Key Housing Needs Statistics – Villages’ For all sources, more detailed housing needs data and a full guide to how to read this data, please visit the Housing StatNav website. Housing StatNav is a partnership project between Eastlight Community Homes and Braintree District Council For more details please visit: https://www.braintree.gov.uk/housing/housing-statnav Key Housing Needs Statistics Snapshot: January 2021 Bures Hamlet About the Parish of Bures Hamlet Population Profile Key Parish Statistics Aged 0-15 Aged 16-24 Aged 25-44 l Population (2011 Census) - 749 l Households (2011 Census) - 325 Aged 45-64 Aged 65-74 Aged 75+ The population is 0.5% of the total l Braintree District population (147,084) Bures Hamlet 19% 5% 21% 30% 14% 11% Over a third of people are 'economically inactive' (retired, carers and homemakers etc) Braintree 32% of people aged 16-74 are 20% 10% 26% 27% 9% 8% District 'economically inactive', compared to the 26% District and 28% East of England proportions Tenure of Housing (2011 Census) 82% 69% Higher proportion of couple or single households over the age of 65 29% of households are couples or single people over the age of 16% 13% 9% 8% 65, compared to the 21% District 2% 1% average Owner occupied Social rented Private rented Living rent free Bures Hamlet Braintree District Housing Association homes to rent in Bures Hamlet There were 14 Housing Association homes to rent in Bures Hamlet as at January 2021. -

Historic Building Recording at King's Farm Barn, Bishops Lane

Historic building recording at King’s Farm Barn, Bishops Lane, Alphamstone, Essex March 2014 report prepared by Chris Lister commissioned by Andrew Stevenson Associates on behalf of Mr and Mrs Franco CAT project ref: 14/03f NGR: TL 8624 3483 (c) ECC HE code: APKF14 Braintree Museum accession code: requested Colchester Archaeological Trust Roman Circus House, Circular Road North, Colchester, Essex, CO2 7GZ tel.: 07436 273304 email: [email protected] CAT Report 767 May 2014 Contents 1 Summary 1 2 Introduction 1 3 Aims 2 4 Building recording methodology 2 5 Historical background 3 6 Descriptive record 7 7 Discussion 10 8 Acknowledgements 12 9 References 12 10 Abbreviations and glossary 12 11 Archive deposition 13 12 Contents of archive 13 Appendices Appendix 1: selected photographs. 15 Appendix 2: full list of digital photographic record 22 (images on accompanying CD) Figures after p 23 EHER summary sheet List of figures Fig 1 Site location. Fig 2 Plan of the barn at King’s Farm, showing phases and alterations. The location and orientation of photographs included in this report are indicated by the numbered arrows. Fig 3 Frame drawing of north-west elevation, indicating the locations of original, re-used and replacement timbers. Fig 4 Frame drawing of south-east elevation, indicating the locations of original, re-used and replacement timbers. Fig 5 Frame drawing of north-east elevation, indicating the locations of original, re-used and replacement timbers. Fig 6 Frame drawing of south-west elevation, indicating the locations of original, re-used and replacement timbers. Fig 7 Cross-section of truss B. -

Spatial Strategy Formulation

Spatial Strategy Formulation Summary of evidence, and how it influenced the spatial strategy in the Publication Draft Local Plan. Braintree District Council - 2017 Publication Draft Local Plan Spatial Strategy Formation The following outlines the formulation of the spatial strategy for the Braintree District Local Plan. It outline how the Plan and evidence base support the principles of sustainable development as set out in the NPPF, a summary of the Council’s evidence base and how it influenced the spatial strategy, and the different spatial strategy options. Publication Draft Spatial Strategy The spatial strategy for the district is set out in the following policies; LPP17 – Housing Provision and Delivery sets out the proposed spatial strategy for the District. LPP18 to LPP22- Strategic growth sites LPP36 – Gypsy and Traveller and Travelling Showpersons Accommodation SP2 – Spatial Strategy for North Essex SP3 – Meeting Housing Need SP4 – Employment and Retail SP7 – Development & Delivery of New Garden Communities in North Essex SP9 – Colchester/Braintree Boarders Garden Community SP10 – West of Braintree Garden Community National Policy The NPPF sets out the three dimensions of sustainable development. An economic role - contributing to building a strong, responsive and competitive economy, by ensuring that sufficient land of the right type is available in the right places and at the right time to support growth and innovation; and by identifying and coordinating development requirements, including the provision of infrastructure; A