From Source to Sea: Scarf Marine and Maritime Panel Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Achbeag, Cullicudden, Balblair, Dingwall IV7

Achbeag, Cullicudden, Balblair, Dingwall Achbeag, Outside The property is approached over a tarmacadam Cullicudden, Balblair, driveway providing parking for multiple vehicles Dingwall IV7 8LL and giving access to the integral double garage. Surrounding the property, the garden is laid A detached, flexible family home in a mainly to level lawn bordered by mature shrubs popular Black Isle village with fabulous and trees and features a garden pond, with a wide range of specimen planting, a wraparound views over Cromarty Firth and Ben gravelled terrace, patio area and raised decked Wyvis terrace, all ideal for entertaining and al fresco dining, the whole enjoying far-reaching views Culbokie 5 miles, A9 5 miles, Dingwall 10.5 miles, over surrounding countryside. Inverness 17 miles, Inverness Airport 24 miles Location Storm porch | Reception hall | Drawing room Cullicudden is situated on the Black Isle at Sitting/dining room | Office | Kitchen/breakfast the edge of the Cromarty Firth and offers room with utility area | Cloakroom | Principal spectacular views across the firth with its bedroom with en suite shower room | Additional numerous sightings of seals and dolphins to bedroom with en suite bathroom | 3 Further Ben Wyvis which dominates the skyline. The bedrooms | Family shower room | Viewing nearby village of Culbokie has a bar, restaurant, terrace | Double garage | EPC Rating E post office and grocery store. The Black Isle has a number of well regarded restaurants providing local produce. Market shopping can The property be found in Dingwall while more extensive Achbeag provides over 2,200 sq. ft. of light- shopping and leisure facilities can be found in filled flexible accommodation arranged over the Highland Capital of Inverness, including two floors. -

From Sail to Steam: London's Role in a Shipbuilding Revolution Transcript

From Sail to Steam: London's Role in a Shipbuilding Revolution Transcript Date: Monday, 24 October 2016 - 1:00PM Location: Museum of London 24 October 2016 From Sail to Steam: London’s Role in a Shipbuilding Revolution Elliott Wragg Introduction The almost deserted River Thames of today, plied by pleasure boats and river buses is a far cry from its recent past when London was the greatest port in the world. Today only the remaining docks, largely used as mooring for domestic vessels or for dinghy sailing, give any hint as to this illustrious mercantile heritage. This story, however, is fairly well known. What is less well known is London’s role as a shipbuilder While we instinctively think of Portsmouth, Plymouth and the Clyde as the homes of the Royal Navy, London played at least an equal part as any of these right up until the latter half of the 19th century, and for one brief period was undoubtedly the world’s leading shipbuilder with technological capability and capacity beyond all its rivals. Little physical evidence of these vast enterprises is visible behind the river wall but when the tide goes out the Thames foreshore gives us glimpses of just how much nautical activity took place along its banks. From the remains of abandoned small craft at Brentford and Isleworth to unique hulked vessels at Tripcockness, from long abandoned slipways at Millwall and Deptford to ship-breaking assemblages at Charlton, Rotherhithe and Bermondsey, these tantalising remains are all that are left to remind us of London’s central role in Britain’s maritime story. -

Review of Burleson

BOOK REVIEWS Stephen Fisher (ed.). Recreation and the Sea. common thread in Waltons case studies of Exeter: Universi ty of Exeter Press, 1997. ix + 181 Brighton, Nice, and San Sebastian, and Cusack pp., figures, maps, tables, photographs. £13.99, and Ryan both recognise its role in the develop- paper; ISBN 0-85989-540-8. Distributed in No rth ment of yachting. On a more practical level, America by Northwestern University Press, improvements in transpo rtation — from steam- Evanston, IL. boats to trains to automobiles — encouraged mass tourism and permitted the emergence of seaside This is a collection of six essays originally pre- resort towns and even resort "clusters." [Walton, sented at a 1993 conference organised by the 46] With the onset of mass tourism, advertising Centre for Maritime Historical Studies at the assumed a key role, as Morgan makes clear for University of Exeter. John Travis writes on Torquay. As for image, Walton and Morgan both English sea-bathing between 1730 and 1900; argue convincingly that, at least until 1939, local John Walton looks at the spread of sea-bathing communities had a large say in how they wished from England where it began to other European to be portrayed to potential visitors. centres during the period 1750 to 1939; Paul There is little with which to quibble in this Thornton provides a regional study of coastal fine collection. Travis offers no explanation for tourism in Cornwall since 1900; Nigel Morgan the nineteenth-century transition in bathing examines the emergence of modern resort activi- circles from a medicinal focus to an emphasis on ties in inter-war Torquay; and Janet Cusack and the physical activity of swimming, though he Roger Ryan write on aspects of English yachting admits that this was "a fundamental ch ange in the history, the former focusing on the Thames and bathing ritual." [16] Citing Perrys work on Corn- south Devon, the latter on the northwest. -

List of Scottish Museums and Libraries with Strong Victorian Collections

Scottish museums and libraries with strong Victorian collections National Institutions National Library of Scotland National Gallery of Scotland National Museums Scotland National War Museum of Scotland National Museum of Costume Scottish Poetry Library Central Libraries The Mitchell Library, Glasgow Edinburgh Central Library Aberdeen Central Library Carnegie Library, Ayr Dick Institute, Kilmarnock Central Library, Dundee Paisley Central Library Ewart Library, Dumfries Inverness Library University Libraries Glasgow University Library University of Strathclyde Library Edinburgh University Library Sir Duncan Rice Library, Aberdeen University of Dundee Library University of St Andrews Library Municipal Art Galleries and Museums Kelvingrove Art Gallery, Glasgow Burrell Collection, Glasgow Aberdeen Art Gallery McManus Galleries, Dundee Perth Museum and Art Gallery Paisley Museum & Art Galleries Stirling Smith Art Gallery & Museum Stewartry Museum, Kirkcudbright V & A Dundee Shetland Museum Clydebank Museum Mclean Museum and Art Gallery, Greenock Hunterian Art Gallery & Museum Piers Art Centre, Orkney City Art Centre, Edinburgh Campbeltown Heritage Centre Montrose Museum Inverness Museum and Art Gallery Kirkcaldy Galleries Literary Institutions Moat Brae: National Centre for Children’s Literature Writers’ Museum, Edinburgh J. M. Barrie Birthplace Museum Industrial Heritage Summerlee: Museum of Scottish Industrial Life, North Lanarkshire Riverside Museum, Glasgow Scottish Maritime Museum Prestongrange Industrial Heritage Museum, Prestonpans Scottish -

Coasts and Seas of the United Kingdom. Region 4 South-East Scotland: Montrose to Eyemouth

Coasts and seas of the United Kingdom Region 4 South-east Scotland: Montrose to Eyemouth edited by J.H. Barne, C.F. Robson, S.S. Kaznowska, J.P. Doody, N.C. Davidson & A.L. Buck Joint Nature Conservation Committee Monkstone House, City Road Peterborough PE1 1JY UK ©JNCC 1997 This volume has been produced by the Coastal Directories Project of the JNCC on behalf of the project Steering Group. JNCC Coastal Directories Project Team Project directors Dr J.P. Doody, Dr N.C. Davidson Project management and co-ordination J.H. Barne, C.F. Robson Editing and publication S.S. Kaznowska, A.L. Buck, R.M. Sumerling Administration & editorial assistance J. Plaza, P.A. Smith, N.M. Stevenson The project receives guidance from a Steering Group which has more than 200 members. More detailed information and advice comes from the members of the Core Steering Group, which is composed as follows: Dr J.M. Baxter Scottish Natural Heritage R.J. Bleakley Department of the Environment, Northern Ireland R. Bradley The Association of Sea Fisheries Committees of England and Wales Dr J.P. Doody Joint Nature Conservation Committee B. Empson Environment Agency C. Gilbert Kent County Council & National Coasts and Estuaries Advisory Group N. Hailey English Nature Dr K. Hiscock Joint Nature Conservation Committee Prof. S.J. Lockwood Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Sciences C.R. Macduff-Duncan Esso UK (on behalf of the UK Offshore Operators Association) Dr D.J. Murison Scottish Office Agriculture, Environment & Fisheries Department Dr H.J. Prosser Welsh Office Dr J.S. Pullen WWF-UK (Worldwide Fund for Nature) Dr P.C. -

Dogger Bank Special Area of Conservation (SAC) MMO Fisheries Assessment 2021

Document Control Title Dogger Bank Special Area of Conservation (SAC) MMO Fisheries Assessment 2021 Authors T Barnfield; E Johnston; T Dixon; K Saunders; E Siegal Approver(s) V Morgan; J Duffill Telsnig; N Greenwood Owner T Barnfield Revision History Date Author(s) Version Status Reason Approver(s) 19/06/2020 T Barnfield; V.A0.1 Draft Introduction and Part V Morgan E Johnston A 06/07/2020 T Barnfield; V.A0.2 Draft Internal QA of V Morgan E Johnston Introduction and Part A 07/07/2020 T Barnfield; V.A0.3 Draft JNCC QA of A Doyle E Johnston Introduction and Part A 14/07/2020 T Barnfield; V.A0.4 Draft Introduction and Part V Morgan E Johnston A JNCC comments 26/07/2020 T Barnfield; V.BC0.1 Draft Part B & C N Greenwood E Johnston 29/07/2020 T Barnfield; V.BC0.2 Draft Internal QA of Part B N Greenwood E Johnston & C 30/07/2020 T Barnfield; V.BC0.3 Draft JNCC QA of A Doyle E Johnston Introduction and Part A 05/08/2020 T Barnfield; V.BC0.4 Draft Part B & C JNCC N Greenwood E Johnston comments 06/08/2020 T Barnfield; V.1.0 Draft Whole document N Greenwood E Johnston compilation 07/08/2020 T Barnfield; V.1.1 Draft Whole document N Greenwood E Johnston Internal QA 18/08/2020 T Barnfield; V.1.2 Draft Whole document A Doyle E Johnston JNCC QA 25/08/2020 T Barnfield; V1.3 Draft Whole Document G7 Leanne E Johnston QA Stockdale 25/08/2020 T Barnfield; V1.4 Draft Update following G7 Leanne E Johnston QA Stockdale 25/01/2021 T Barnfield; V2.0 – 2.4 Draft Updates following NGreenwood; K Saunders; new data availability J Duffill Telsnig T Dixon; E and QA Siegal 01/02/2021 T Barnfield; V2.5 Final Finalise comments Nick Greenwood K Saunders; E and updates Siegal 1 Dogger Bank Special Area of Conservation (SAC) MMO Fisheries Assessment 2020 Contents Document Control ........................................................................................................... -

An Overview of the Lithostratigraphical Framework for the Quaternary Deposits on the United Kingdom Continental Shelf

An overview of the lithostratigraphical framework for the Quaternary deposits on the United Kingdom continental shelf Marine Geoscience Programme Research Report RR/11/03 HOW TO NAVIGATE THIS DOCUMENT Bookmarks The main elements of the table of contents are book- marked enabling direct links to be followed to the principal section headings and sub- headings, figures, plates and tables irrespective of which part of the document the user is viewing. In addition, the report contains links: from the principal section and subsection headings back to the contents page, from each reference to a figure, plate or table directly to the corresponding figure, plate or table, from each page number back to the contents page. RETURN TO CONTENTS PAGE BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MARINE GEOSCIENCE PROGRAMME The National Grid and other RESEARCH REPORT RR/11/03 Ordnance Survey data are used with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Licence No: 100017897/2011. Keywords Group; Formation; Atlantic margin; North Sea; English Channel; Irish An overview of the lithostratigraphical Sea; Quaternary. Front cover framework for the Quaternary deposits Seismic cross section of the Witch Ground Basin, central North on the United Kingdom continental Sea (BGS 81/04-11); showing flat-lying marine sediments of the Zulu Group incised and overlain shelf by stacked glacial deposits of the Reaper Glacigenic Group. Bibliographical reference STOKER, M S, BALSON, P S, LONG, D, and TAppIN, D R. 2011. An overview of the lithostratigraphical framework for the Quaternary deposits on the United Kingdom continental shelf. British Geological Survey Research Report, RR/11/03. -

'Scotland: Identity, Culture and Innovation'

Fulbright - Scotland Summer Institute ‘Scotland: Identity, Culture and Innovation’ University of Dundee University of Strathclyde, Glasgow 6 July-10 August 2013 Tay Rail Bridge, Dundee opened 13th July, 1887 The Clyde Arc, Glasgow opened 18th September, 2006 Welcome to Scotland Fàilte gu Alba We are delighted that you have come to Scotland to join the first Fulbright-Scotland Summer Institute. We would like to offer you the warmest of welcomes to the University of Dundee and the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow. Scotland is a fascinating country with a rich history and a modern and cosmopolitan outlook; we look forward to introducing you to our culture, identity and pioneering spirit of innovation. You will experience our great cities and the breathtaking scenery of the Scottish Highlands and we hope you enjoy your visit and feel inspired to return to Scotland in the future. Professor Pete Downes Principal and Vice-Chancellor, University of Dundee “Education and travel transforms lives and is central to our vision at the University of Dundee, which this year has been ranked one of the top ten universities in the UK for teaching and learning. We are delighted to bring young Americans to Dundee and to Scotland for the first Fulbright- Scotland Summer Institute to experience our international excellence and the richness and variety of our country and culture.” Professor Sir Jim McDonald Principal and Vice-Chancellor, University of Strathclyde “Strathclyde endorses the Fulbright objectives to promote leadership, learning and empathy between nations through educational exchange. The partnership between Dundee and Strathclyde, that has successfully attracted this programme, demonstrates the value of global outreach central to Scotland’s HE reputation. -

Location and Destination in Alasdair Mac Mhaigshstir Alasdair's 'The

Riach, A. (2019) Location and destination in Alasdair mac Mhaigshstir Alasdair’s ‘The Birlinn of Clanranald’. In: Szuba, M. and Wolfreys, J. (eds.) The Poetics of Space and Place in Scottish Literature. Series: Geocriticism and spatial literary studies. Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, pp. 17-30. ISBN 9783030126445. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/188312/ Deposited on: 13 June 2019 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Location and Destination in Alasdair mac Mhaigshstir Alasdair’s ‘The Birlinn of Clanranald’ Alan Riach FROM THE POETICS OF SPACE AND PLACE IN SCOTTISH LITERATURE, MONIKA SZUBA AND JULIEN WOLFREYS, EDS., (CHAM, SWITZERLAND: PALGRAVE MACMILLAN, 2019), PP.17-30 ‘THE BIRLINN OF CLANRANALD’ is a poem which describes a working ship, a birlinn or galley, its component parts, mast, sail, tiller, rudder, oars and the cabes (or oar-clasps, wooden pommels secured to the gunwale) they rest in, the ropes that connect sail to cleats or belaying pins, and so on, and the sixteen crewmen, each with their appointed role and place; and it describes their mutual working together, rowing, and then sailing out to sea, from the Hebrides in the west of Scotland, from South Uist to the Sound of Islay, then over to Carrickfergus in Ireland. The last third of the poem is an astonishing, terrifying, exhilarating description of the men and the ship in a terrible storm that blows up, threatening to destroy them, and which they pass through, only just making it to safe harbour, mooring and shelter. -

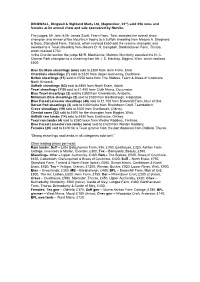

DINGWALL, Dingwall & Highland Marts

DINGWALL, Dingwall & Highland Marts Ltd, (September, 23rd) sold 358 rams and females at its annual show and sale sponsored by Norvite. The judges, Mr John & Mr James Scott, Fearn Farm, Tain, awarded the overall show champion and winner of the Mountrich trophy to a Suffolk shearling from Messrs A. Shepherd & Sons, Stonyford Farm, Tarland, which realised £650 and the reserve champion was awarded to a Texel shearling from Messrs D. N. Campbell, Bardnaclaven Farm, Thurso, which realised £700. In the Cheviot section the judge Mr R. MacKenzie, Muirton, Munlochy awarded the N. C. Cheviot Park champion to a shearling from Mr J. S. MacKay, Biggins, Wick, which realised £600. Blue Du Main shearlings (one) sold to £500 from Hern Farm, Errol. Charollais shearlings (7) sold to £320 from Upper Auchenlay, Dunblane. Beltex shearlings (15) sold to £550 twice from The Stables, Fearn & Braes of Coulmore, North Kessock. Suffolk shearlings (63) sold to £850 from North Essie, Adziel. Texel shearlings (119) sold to £1,450 from Clyth Mains, Occumster. Blue Texel shearlings (2) sold to £380 from Greenlands, Arabella. Millenium Blue shearlings (2) sold to £500 from Bardnaheigh, Harpsdale. Blue Faced Leicester shearlings (46) sold to £1,100 from Broomhill Farm, Muir of Ord. Dorset Poll shearlings (4) sold to £300 twice from Rheindown Croft, Teandalloch. Cross shearlings (19) sold to £600 from Overhouse, Orkney. Cheviot rams (32) sold to £600 for the champion from Biggins, Wick. Suffolk ram lambs (14) sold to £420 from Easthouse, Orkney. Texel ram lambs (4) sold to £380 twice from Wester Raddery, Fortrose. Blue Faced Leicester ram lambs (one) sold to £420 from Wester Raddery. -

The MARINER's MIRROR the JOURNAL of ~Ht ~Ocitt~ for ~Autical ~Tstarch

The MARINER'S MIRROR THE JOURNAL OF ~ht ~ocitt~ for ~autical ~tstarch. Antiquities. Bibliography. Folklore. Organisation. Architecture. Biography. History. Technology. Art. Equipment. Laws and Customs. &c., &c. Vol. III., No. 3· March, 1913. CONTENTS FOR MARCH, 1913. PAGE PAGE I. TWO FIFTEENTH CENTURY 4· A SHIP OF HANS BURGKMAIR. FISHING VESSELS. BY R. BY H. H. BRINDLEY • • 8I MORTON NANCE • • . 65 5. DocuMENTS, "THE MARINER's 2. NOTES ON NAVAL NOVELISTS. MIRROUR" (concluded.) CON· BY OLAF HARTELIE •• 7I TRIBUTED BY D. B. SMITH. 8S J. SOME PECULIAR SWEDISH 6. PuBLICATIONS RECEIVED . 86 COAST-DEFENCE VESSELS 7• WORDS AND PHRASES . 87 OF THE PERIOD I]62-I8o8 (concluded.) BY REAR 8. NOTES . • 89 ADMIRAL J. HAGG, ROYAL 9· ANSWERS .. 9I SwEDISH NAVY •• 77 IO. QUERIES .. 94 SOME OLD-TIME SHIP PICTURES. III. TWO FIFTEENTH CENTURY FISHING VESSELS. BY R. MORTON NANCE. WRITING in his Glossaire Nautique, concerning various ancient pictures of ships of unnamed types that had come under his observation, Jal describes one, not illustrated by him, in terms equivalent to these:- "The work of the engraver, Israel van Meicken (end of the 15th century) includes a ship of handsome appearance; of middling tonnage ; decked ; and bearing aft a small castle that has astern two of a species of turret. Her rounded bow has a stem that rises up with a strong curve inboard. Above the hawseholes and to starboard of the stem is placed the bowsprit, at the end 66 SOME OLD·TIME SHIP PICTURES. of which is fixed a staff terminating in an object that we have seen in no other vessel, and that we can liken only to a many rayed monstrance. -

Youth Travel SAMPLE ITINERARY

Youth Travel SAMPLE ITINERARY For all your travel trade needs: www.visitscotlandtraveltrade.com Day One Riverside Museum Riverside Museum is Glasgow's award-winning transport museum. With over 3,000 objects on display there's everything from skateboards to locomotives, paintings to prams and cars to a Stormtrooper. Your clients can get hands on with our interactive displays, walk through Glasgow streets and visit the shops, bar and subway. Riverside Museum Pointhouse Place, Glasgow, G3 8RS W: http://www.glasgowlife.org.uk/museums Glasgow Powerboats A unique city-centre experience. Glasgow Powerboats offer fantastic fast boat trip experiences on the River Clyde from Pacific Quay in the heart of Glasgow right outside the BBC Scotland HQ. From a 15-minute City Centre transfer to a full day down the water they can tailor trips to your itinerary. Glasgow Powerboats 50 Pacific Quay, Glasgow, G51 1EA W: https://powerboatsglasgow.com/ Glasgow Science Centre Glasgow Science Centre is one of Scotland's must-see visitor attractions. It has lots of activities to keep visitors of all ages entertained for hours. There are two acres of interactive exhibits, workshops, shows, activities, a planetarium and an IMAX cinema. Your clients can cast off in The Big Explorer and splash about in the Waterways exhibit, put on a puppet show and master the bubble wall. Located on the Pacific Quay in Glasgow City Centre just a 10-minute train journey from Glasgow Central Station. Glasgow Science Centre 50 Pacific Quay, Glasgow, G51 1EA For all your travel trade needs: www.visitscotlandtraveltrade.com W: https://www.glasgowsciencecentre.org/ Scottish Maritime Museum Based in the West of Scotland, with sites in Irvine and Dumbarton, the Scottish Maritime Museum holds an important nationally recognised collection, encompassing a variety of historic vessels, artefacts, fascinating personal items and the largest collection of shipbuilding tools and machinery in the country.