India Country Brief for the Water Sector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

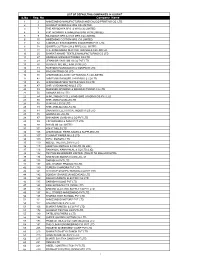

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA U55101DL1998PTC094457 RVS HOTELS AND RESORTS 02700032 BANSAL SHYAM SUNDER U70102AP2005PTC047718 SHREEMUKH PROPERTIES PRIVATE 02700065 CHHIBA SAVITA U01100MH2004PTC150274 DEJA VU FARMS PRIVATE LIMITED 02700070 PARATE VIJAYKUMAR U45200MH1993PTC072352 PARATE DEVELOPERS P LTD 02700076 BHARATI GHOSH U85110WB2007PTC118976 ACCURATE MEDICARE & 02700087 JAIN MANISH RAJMAL U45202MH1950PTC008342 LEO ESTATES PRIVATE LIMITED 02700109 NATESAN RAMACHANDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700110 JEGADEESAN MAHENDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700126 GUPTA JAGDISH PRASAD U74210MP2003PTC015880 GOPAL SEVA PRIVATE LIMITED 02700155 KRISHNAKUMARAN NAIR U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700157 DHIREN OZA VASANTLAL U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700183 GUPTA KEDAR NATH U72200AP2004PTC044434 TRAVASH SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS 02700187 KUMARASWAMY KUNIGAL U93090KA2006PLC039899 EMERALD AIRLINES LIMITED 02700216 JAIN MANOJ U15400MP2007PTC020151 CHAMBAL VALLEY AGRO 02700222 BHAIYA SHARAD U45402TN1996PTC036292 NORTHERN TANCHEM PRIVATE 02700226 HENDIN URI ZIPORI U55101HP2008PTC030910 INNER WELLSPRING HOSPITALITY 02700266 KUMARI POLURU VIJAYA U60221PY2001PLC001594 REGENCY TRANSPORT CARRIERS 02700285 DEVADASON NALLATHAMPI U72200TN2006PTC059044 ZENTERE SOLUTIONS PRIVATE 02700322 GOPAL KAKA RAM U01400UP2007PTC033194 KESHRI AGRI GENETICS PRIVATE 02700342 ASHISH OBERAI U74120DL2008PTC184837 ASTHA LAND SCAPE PRIVATE 02700354 MADHUSUDHANA REDDY U70200KA2005PTC036400 -

Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas the Indian New Wave

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 28 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas K. Moti Gokulsing, Wimal Dissanayake, Rohit K. Dasgupta The Indian New Wave Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203556054.ch3 Ira Bhaskar Published online on: 09 Apr 2013 How to cite :- Ira Bhaskar. 09 Apr 2013, The Indian New Wave from: Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas Routledge Accessed on: 28 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203556054.ch3 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. 3 THE INDIAN NEW WAVE Ira Bhaskar At a rare screening of Mani Kaul’s Ashad ka ek Din (1971), as the limpid, luminescent images of K.K. Mahajan’s camera unfolded and flowed past on the screen, and the grave tones of Mallika’s monologue communicated not only her deep pain and the emptiness of her life, but a weighing down of the self,1 a sense of the excitement that in the 1970s had been associated with a new cinematic practice communicated itself very strongly to some in the auditorium. -

Dimple Kapadia Is

B-10 | Friday, June 14, 2019 BOLLYWOOD www.WeeklyVoice.com Actor-Director Karnad Dead; Cremated Without Fanfare Bengaluru: Girish Karnad, a suburb, with his bereaved family, Sahitya Akademi honour. ar in the University of Oxford, Jnanpith winner, multi-lingual relatives and friends following it In a career spanning six de - where he studied philosophy, scholar, master playwright, in a convoy without fanfare,- po cades, Karnad acted in Kannada, politics and economics. screenwriter, actor, director and lice security or escort. Hindi and Marathi ilms, in both Karnad may be best remem- an iconic personality in India’s “Though the Karnataka gov- mainstream and parallel cinema. bered as Swami’s father in ‘Mal- cultural landscape, died here on ernment decided to conduct Kar- He also featured in television se- gudi Days’ or as the presenter Monday. He was 81. nad’s last rites with state honours, rials, including the famous ‘Mal- of Doordarshan’s science show “Karnad died at his home at we have decided to respect his gudi Days’, based on the works “Turning Point”, while for Hindi around 8.30 a.m. due to age-re- wishes and allowed his family of renowned Indian English au- movie audiences, his roles in lated symptoms,” the Karnataka to do it accordingly,” an oficial thor, R.K. Narayan. “Manthan”, “Nishant”, “Pukar”, Chief Minister’s ofice said. said. The family also declined to He bagged four Filmfare “Iqbal”, “Dor” and “Ek Tha Ti- The veteran artist is survived keep his body for public viewing. awards, including three for best ger” left an impact. by his widow Saraswathy Ga- Karnad succumbed to multi- director for “Vamsha Vriksha” in Karnad served as director of napathy, his son Raghu Amay andorgan failure at his residence on 1972, “Kaadu” in 1974 and “On- the state-run Film and Television daughter Shalmali Radha. -

Smita Patil: Fiercely Feminine

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2017 Smita Patil: Fiercely Feminine Lakshmi Ramanathan The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2227 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SMITA PATIL: FIERCELY FEMININE BY LAKSHMI RAMANATHAN A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2017 i © 2017 LAKSHMI RAMANATHAN All Rights Reserved ii SMITA PATIL: FIERCELY FEMININE by Lakshmi Ramanathan This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts. _________________ ____________________________ Date Giancarlo Lombardi Thesis Advisor __________________ _____________________________ Date Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Acting Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT SMITA PATIL: FIERCELY FEMININE by Lakshmi Ramanathan Advisor: Giancarlo Lombardi Smita Patil is an Indian actress who worked in films for a twelve year period between 1974 and 1986, during which time she established herself as one of the powerhouses of the Parallel Cinema movement in the country. She was discovered by none other than Shyam Benegal, a pioneering film-maker himself. She started with a supporting role in Nishant, and never looked back, growing into her own from one remarkable performance to the next. -

Recognising and Supporting Territories and Areas Conserved by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities: Global Overview and National Case Studies

Secretariat of the CBD Technical Series No. 64 Convention on Biological Diversity RECOGNISING64 AND SUPPORTING TERRITORIES AND AREAS CONSERVED BY INDIGENOUS PEOPLES AND LOCAL COMMUNITIES Global overview and national case studies Published by the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. ISBN: 92-9225-426-X (print version); ISBN: 92-9225-425-1 (web version) Copyright © 2012, Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views reported in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the Convention on Biological Diversity, the Parties to the Convention, or those of the reviewers. This publication may be reproduced for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holders, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. The Secretariat of the Convention would appreciate receiving a copy of any publications that uses this document as a source. Citation Kothari, Ashish with Corrigan, Colleen, Jonas, Harry, Neumann, Aurélie, and Shrumm, Holly. (eds). 2012. Recognising and Supporting Territories and Areas Conserved By Indigenous Peoples And Local Communities: Global Overview and National Case Studies. Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, ICCA Consortium, Kalpavriksh, and Natural Justice, Montreal, Canada. Technical Series no. 64, 160 pp. For further information please contact Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity World Trade Centre 413 St. -

Desertion of Rural Theme from Hindi Cinema: a Study

International Journal of Humanities & Social Science Studies (IJHSSS) A Peer-Reviewed Bi-monthly Bi-lingual Research Journal ISSN: 2349-6959 (Online), ISSN: 2349-6711 (Print) Volume-III, Issue-V, March 2017, Page No. 335-339 Published by Scholar Publications, Karimganj, Assam, India, 788711 Website: http://www.ijhsss.com Desertion of Rural theme from Hindi Cinema: A Study Neema Negi Research Scholar, Department of Journalism and Communication, Dev Sanskriti Vishwavidyalaya, Hardwar, U.K., India Abstract Hindi Cinema caters different themes from last 100 glorious years and in earlier phase it reflects the nation’s conflict, difficulties and struggle of a common man in a true manner. In past era one of the major themes rural has been an integral part of Bollywood storytelling. However over the year’s Hindi cinema has changed in terms of film making, content, representation of issues and technological changes. But during the transition of modern Cinema some of the popular themes have vanished. Cinema become bold and creative today and brings different genres with ample of independent filmmakers. The present paper deals with the study of films which depicted the village theme and also explore the causes of disappearance of village theme. Keywords: village theme, Hindi Cinema, farmers, social issues, vanished I- Disappearance of village theme: Indian Cinema acknowledged for the largest producer of films which caters the widest themes and genres from past 100 magnificent years. In every era Hindi cinema represents the social relevant issues in a very different narrative style. In the past six decades Hindi cinema has played a significant role in nation-building, constructing a national awareness, portraying an ideal family system, attacking terrorism, criticizing class prejudice and propagating various phenomena such as globalization, westernization, urbanization and modernization in India. -

Notice Degree & Self Financing Course

NARSEE MONJEE COLLEGE OF COMMERCE & ECONOMICS (Autonomous) VILE PARLE (WEST), MUMBAI 400 056 21st June, 2021 NOTICE DEGREE & SELF FINANCING COURSE Students of S.Y/TY B.COM/BMS/BAF/BFM/BSc.IT/BCom(Hons) are hereby informed that the Roll Call for the Academic year 2021-22 is displayed on the college website. Students are required to note their Division, Roll Number. Regular (Online) Lectures for above mentioned classes shall commence from 23rd June, 2021 as per the time table. Dr. Parag Ajagaonkar Principal SVKM's Narsee Monjee College of Commerce & Economics (Autonomous) TYBCOM - TIME TABLE - 2021- 2022 A DIVISION ROOM NO. 13 PERIOD TIME MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY TAX DP CSA FAA, SD CA SJD COMM PA FAA SD MV A1 (PV, I 06:45 LAB6)& A2(GJ,E LAB) COMM PA FAA , SD CA SJD OR MV TAX NB/CSA II 07:45 MV BREAK ( 8:45 am to 8:55 am) TAX DP III 08:55 OR SDK CA SJD COMM RB ECO KV FAA SD IV 09:55 ECO KV OR SDK ECO KV CA SJD Dr. Parag Ajagaonkar Principal SVKM's Narsee Monjee College of Commerce & Economics (Autonomous) TYBCOM - TIME TABLE - 2021- 2022 B DIVISION ROOM NO. 14 PERIOD TIME MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY I 06:45 COMM PA CA SJD FAA SD ECO VF TAX DP CSA BP B1(SDK, E LAB) & B2(MV,LAB6) II 07:45 COMM PA FAA SD IP RW IP RW TAX NB/CSA BP BREAK ( 8:45 am to 8:55 am) TAX DP III 08:55 CA JB FAA SD CA JB ECO NC IP RW ECO NC IV 09:55 FAA SD COMM RB CA JB Dr. -

Columbia Global Centers | Amman

Columbia Global Centers | Amman .............................................................................................. 3 Columbia Global Centers | Beijing ............................................................................................. 17 Columbia Global Centers | Istanbul ............................................................................................ 30 Columbia Global Centers | Mumbai ........................................................................................... 41 Columbia Global Centers | Nairobi ............................................................................................. 48 Columbia Global Centers | Paris ................................................................................................. 52 Columbia Global Centers | Rio de Janeiro ................................................................................. 62 Columbia Global Centers | Santiago ........................................................................................... 69 Columbia Global Centers | Tunis ................................................................................................ 77 Columbia Global Centers | Amman Center Launch: March 2009 Website: http://globalcenters.columbia.edu/amman Email: [email protected] Address: 5 Moh’d Al Sa’d Al Batayneh St., King Hussein Park, P.O. Box 144706, Amman 11814 Jordan Director Biography SAFWAN M. MASRI [email protected] Professor Safwan M. Masri is Executive Vice President for Global Centers and Global Development at Columbia -

Annual Report 2011-2012

Printed on Recycled Paper ANNUAL REPORT 2011-2012 #599, 12th Main, HAL 2nd Stage,Indiranagar, Bengaluru-560008, Karnataka, India Email: [email protected] Phone: +91 (080) 41698941, 41698942 Fax: +91 (080) 41698943 www.arghyam.org Acronyms ACT Arid Communities and Technologies SBT Soil Biotechnology ACWADAM Advanced Centre for Water Resources SCOPE Society for Community Participation Development and Management and Empowerment ASER Annual Status of Education Report SHG Self-Help Group BIRD-K BAIF Institute for Rural Development- SOPPECOM Society for Promoting Participative Karnataka Ecosystem Management CDL Communication for Development and SWM Solid Waste Management Learning TMC Town Municipal Council DMA Directorate of Municipal Administration UAS University of Agricultural Sciences Ecosan Ecological sanitation UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund FES Foundation for Ecological Security VJNNS Visakha Jilla Nava Nirmana Samithi HUDCO Housing and Urban Development WASH Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Corporation WatSan Water and Sanitation IDWM Integrated Domestic Water WASSAN Watershed Support Services and Management Activities Network IIHS Indian Institute for Human Settlements WQM Water Quality Management IISc Indian Institute of Science WSP Water and Sanitation Programme ILCS Integrated Low Cost Sanitation WSSCC Water Supply & Sanitation IUWM Integrated Urban Water Management Collaborative Council IWP India Water Portal MDWS Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation MGNREGA Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act MoEF Ministry of Environment and Forests NEERI National Environmental Engineering Research Institute NGO Non-Government Organisation NITK National Institute of Technology Karnataka PRA Participatory Rural Appraisal PAHELI People’s Audit of Health, Education and Livelihoods Reference, partial reproduction and transmission by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise are allowed if the copyright holder is acknowledged. -

S.No Reg. No Company Name 1 2 AHMEDABAD MANUFACTURING and CALICO PRINTING CO

LIST OF DEFAULTING COMPANIES IN GUJRAT S.No Reg. No Company_Name 1 2 AHMEDABAD MANUFACTURING AND CALICO PRINTING CO. LTD. 2 3 GUJARAT GINNING & MFG CO.LIMITED. 3 7 THE ARYODAYA SPG & WVG.CO.LIMITED. 4 8 40817HCHOWK & AHMEDABAD MFG CO.LIMITED. 5 9 RAJNAGAR SPG & WVG MFG.CO.LIMITED. 6 10 HMEDABAD COTTON MFG. CO.LIMITED. 7 12 12DISPLAY STATUSSTEEL INDUSTRIES PVT. LTD. 8 18 ISHWER COTTON G.N.& PRES.CO.LIMITED. 9 22 THE AHMEDABAD NEW COTTON MILLS CO.LIMITED. 10 25 BHARAT KHAND TEXTILE MANUFACTURING CO LTD 11 27 HIMABHAI MANUFACTURING CO LTD 12 29 JEHANGIR VAKIL MILLS CO PVT LTD 13 30 GUJARAT OIL MILL & MFG CO LTD 14 31 RUSTOMJI MANGALDAS & COMPANY LTD 15 34 FINE KNITTING CO LTD 16 40 AHMEDABAD LAXMI COTTON MILLS CO.LIMITED. 17 42 AHMEDABAD KAISER-I-HIND MILLS CO LTD 18 45 AHMEDABAD NEW TEXTILE MILS CO LTD 19 47 SHRI VIVEKANAND MILLS LTD 20 49 MARSDEN SPINNING & MANUFACTURING CO LTD 21 50 ASHOKA MILLS LTD. 22 54 AHMEDABAD CYCLE & MOTORS TRADING CO PVT LTD 23 68 SHRI AMRUTA MILLS LTD 24 78 VIJAY MILLS CO LTD 25 79 SHRI ARBUDA MILLS LTD. 26 81 DHARWAR ELECTRICAL INDUSTRIES LTD 27 85 ANANTA MILLS LTD 28 87 BHIKABHAI JIVABHAI & CO PVT LTD 29 89 J R VAKHARIA & SONS PVT LTD 30 99 BIHARI MILLS LIMITED 31 101 ROHIT MILLS LTD 32 106 AHMEDABAD FIBRE-SALES & SUPPLIES LTD 33 107 GUJARAT PAPER MILLS LTD 34 109 IDEAL MOTORS LTD 35 110 MODEL THEATRES PVT LTD 36 115 HIMATLAL MOTILAL & CO LTD.(IN LIQ.) 37 116 RAMANLAL KANAIYALAL & CO LTD.(LIQ). -

Teaching India with Popular Feature Films

Promising Practices Teaching India with Popular Feature Films A Guide for High School and College Teachers Gowri Parameswaran Introduction organized to fight for their independence ladder by instituting the quota system in and they finally succeeded in 1947. higher education and government positions. Popular films tell us a lot about the Before the British left, they divided However, life for most Shudras and Dalits culture where they are seen and enjoyed the sub-continent into two nations, ac- (the untouchables) is still oppressive. even though they may not reflect “reality” ceding to some Muslim demands for their in the way that academics may want to own country by creating Pakistan. Since The Arts portray a country. Popular films get at the its independence India has burgeoned into deepest longings and fears of their viewer- The Indian subcontinent has a rich the second most populous country and the tradition of both the fine and perform- ship and their biggest hopes for the future. largest democracy on earth. Teaching India through popular films ing arts. There have been a number of influences on Indian sculpture, painting, is particularly important because that Cultural Information country is the largest producer of films in architecture, dance, drama, and writing. the world and claims some of the largest India is an extremely diverse country Some of the earliest and most profound markets for films. with a high degree of cultural continuity as influences have been Buddhist. The char- This article lists and describes some well as syncretism. The Indian constitution acteristic Buddhist rock-cut sculptures popular feature films that teachers can recognizes 22 Indian languages and there were later imitated by Hindus and Jains. -

Volunteering in India

VOLUNTEERING IN INDIA Contexts, Perspectives and Discourses 1 Foreword Volunteerism has long been an integral part of the Indian society shaped by traditions and value systems rooted in the religion and cultural interactions. The volunteers from diverse backgrounds have gone about celebrating the spirit of volunteerism in the best manner they know – rendering selfless service to their fellow beings and the community at large. The observance of International Year of Volunteers (IYV) in 2001 underscores the importance of people-to-people relations as core values of volunteerism. The resolution adopted by the UN General Assembly to mark the Tenth Anniversary of the International Year of Volunteers (IYV+10) in 2011 rekindled the spirit of volunteerism and provided the opportunity to reflect on the status and growth of volunteerism worldwide. The role of volunteers in creation and development of social capital, civic engagement and social cohesion is now well documented. Against the backdrop of challenges, exciting new avenues for people to volunteer have opened up. It is also significant to note the role of technological revolution and its contribution to new forms of volunteering like micro-volunteering and online volunteering. These are going to be the key in future forms of volunteering discourses. It is notable that eighty-seven per cent of people aged 15 to 24 live in developing countries. They can play an important role to achieve the Millennium Development Goals adopting various ways to engage. Tenth International year of volunteers (IYV+10) offered the opportunity to the youth world over to further the volunteering agenda through their creativity, energy and commitment.