Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Construction of the Problematic Female Television Audience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

The ABSOLUTE Best Way to Follow Along with This Bible Study: – Download/Install the FREE KJV Bible to Follow Along

The ABSOLUTE Best Way to Follow Along with This Bible Study: www.e-sword.net – download/install the FREE KJV Bible to follow along. Table of Contents: Drivers and Captives. A Study on Hebrew Words and Isaiah 14:3. How the “Story” is Hidden in the Definitions. How to “create”. The “Scholars” Lie to You. Foolish False Foundations. We Were ALL Born Enemies of God – How and Why? How YOU Messed Up (How we all messed up). We will “consider” Lucifer as a “ ______ ” … well, you will find out. The Beginning – Before the Beginning. Image of God. Learn who Adam really was. The Foundation of Salvation. The Architecture of Salvation. An Honest, Individual, Salvation Receiving Prayer for the Captives. Drivers and the Captives Luke 4:18 The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he hath anointed me to preach the gospel to the poor; he hath sent me to heal the brokenhearted, to preach deliverance to the CAPTIVES, and recovering of SIGHT to the blind, to set at liberty them that are bruised, Concept: Drivers vs Captives. Hypothetical scenario: You and your family live in a rather small town. Your father is a very well- known, respected and upstanding man in your town. Your father owns a few small businesses and is also one of the voters approved elected Judges of the town in the court system. Your mother is also well known and respected. One day your two brothers approach you and say, “Hey, get in the back seat of the car and take a road trip with us.” You have no reason not to trust your two brothers, so it is an easy decision to get in the back seat of the car and go on the road trip with them. -

Razorcake Issue #82 As A

RIP THIS PAGE OUT WHO WE ARE... Razorcake exists because of you. Whether you contributed If you wish to donate through the mail, any content that was printed in this issue, placed an ad, or are a reader: without your involvement, this magazine would not exist. We are a please rip this page out and send it to: community that defi es geographical boundaries or easy answers. Much Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. of what you will fi nd here is open to interpretation, and that’s how we PO Box 42129 like it. Los Angeles, CA 90042 In mainstream culture the bottom line is profi t. In DIY punk the NAME: bottom line is a personal decision. We operate in an economy of favors amongst ethical, life-long enthusiasts. And we’re fucking serious about it. Profi tless and proud. ADDRESS: Th ere’s nothing more laughable than the general public’s perception of punk. Endlessly misrepresented and misunderstood. Exploited and patronized. Let the squares worry about “fi tting in.” We know who we are. Within these pages you’ll fi nd unwavering beliefs rooted in a EMAIL: culture that values growth and exploration over tired predictability. Th ere is a rumbling dissonance reverberating within the inner DONATION walls of our collective skull. Th ank you for contributing to it. AMOUNT: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc., a California not-for-profit corporation, is registered as a charitable organization with the State of California’s COMPUTER STUFF: Secretary of State, and has been granted official tax exempt status (section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code) from the United razorcake.org/donate States IRS. -

ABSTRACT “The Good Angel of Practical Fraternity:” the Ku Klux Klan in Mclennan County, 1915-1924. Richard H. Fair, M.A. Me

ABSTRACT “The Good Angel of Practical Fraternity:” The Ku Klux Klan in McLennan County, 1915-1924. Richard H. Fair, M.A. Mentor: T. Michael Parrish, Ph.D. This thesis examines the culture of McLennan County surrounding the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s and its influence in central Texas. The pervasive violent nature of the area, specifically cases of lynching, allowed the Klan to return. Championing the ideals of the Reconstruction era Klan and the “Lost Cause” mentality of the Confederacy, the 1920s Klan incorporated a Protestant religious fundamentalism into their principles, along with nationalism and white supremacy. After gaining influence in McLennan County, Klansmen began participating in politics to further advance their interests. The disastrous 1922 Waco Agreement, concerning the election of a Texas Senator, and Felix D. Robertson’s gubernatorial campaign in 1924 represent the Klan’s first and last attempts to manipulate politics. These failed endeavors marked the Klan’s decline in McLennan County and Texas at large. “The Good Angel of Practical Fraternity:” The Ku Klux Klan in McLennan County, 1915-1924 by Richard H. Fair, B.A. A Thesis Approved by the Department of History ___________________________________ Jeffrey S. Hamilton, Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ T. Michael Parrish, Ph.D., Chairperson ___________________________________ Thomas L. Charlton, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Stephen M. Sloan, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Jerold L. Waltman, Ph.D. Accepted by the Graduate School August 2009 ___________________________________ J. -

The BG News May 22, 1996

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 5-22-1996 The BG News May 22, 1996 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News May 22, 1996" (1996). BG News (Student Newspaper). 6019. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/6019 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Inside the News Nation Opinion • Tom Mather considers growing up State* Task force begins anti-smog message Divers continue search for victims following plane crash Nation • Women say they were harassed at work E W S Page 4 Wednesday, May 22, 1996 Bowling Green, Ohio Volume 83, Issue 132 The News' Freemen abort surrender talks Briefs Tom Laceky wild gestures during the discussion. new player on the FBI team gave handshakes, the new participant vehicle, but did not come to the ne- Man.asked to leave The Associated Press Other Freemen and some FBI Freeman leaders a sheaf of papers. handed the several pages of papers gotiating table. They sat in their vehi- agents looked on. After the conver- Duke offered no explanation or in- to Edwin Claris and Russell Landers, cle out of sight of the reporters and church property JORDAN, Mont. - Surrender talks sation ended, the Freemen conting- formation on what was in the papers the only Freemen attending Monday. -

D:\My Documents\Desktop\Website\Pages

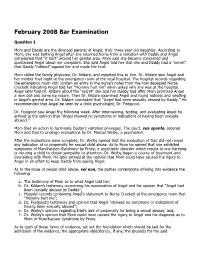

February 2008 Bar Examination Question 1 Mom and Daddy are the divorced parents of Angel, their three year old daughter. According to Mom, she was bathing Angel after she returned home from a visitation with Daddy and Angel complained that “it hurt” around her genital area. Mom said she became concerned and questioned Angel about her complaint. She said Angel told her that she and Daddy had a “secret” that Daddy “rubbed” against her and made her hurt. Mom called the family physician, Dr. Kildare, and reported this to him. Dr. Kildare saw Angel and her mother that night at the emergency room at the local hospital. The hospital records regarding the emergency room visit contain an entry in the nurse’s notes from the now deceased Nurse Crockett indicating Angel told her “Mommy hurt me” when asked why she was at the hospital. Angel later told Dr. Kildare about the “secret” she and her Daddy had after Mom promised Angel a new doll and some ice cream. Then Dr. Kildare examined Angel and found redness and swelling in Angel’s genital area. Dr. Kildare concluded that “Angel had been sexually abused by Daddy.” He recommended that Angel be seen by a child psychologist, Dr. Feelgood. Dr. Feelgood saw Angel the following week. After interviewing, testing, and evaluating Angel he arrived at the opinion that “Angel showed no symptoms or indications of having been sexually abused.” Mom filed an action to terminate Daddy’s visitation privileges. The court, sua sponte, ordered Mom and Dad to undergo evaluations by Dr. Marcus Welby, a psychiatrist. -

9/11 Report”), July 2, 2004, Pp

Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page i THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page v CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Tables ix Member List xi Staff List xiii–xiv Preface xv 1. “WE HAVE SOME PLANES” 1 1.1 Inside the Four Flights 1 1.2 Improvising a Homeland Defense 14 1.3 National Crisis Management 35 2. THE FOUNDATION OF THE NEW TERRORISM 47 2.1 A Declaration of War 47 2.2 Bin Ladin’s Appeal in the Islamic World 48 2.3 The Rise of Bin Ladin and al Qaeda (1988–1992) 55 2.4 Building an Organization, Declaring War on the United States (1992–1996) 59 2.5 Al Qaeda’s Renewal in Afghanistan (1996–1998) 63 3. COUNTERTERRORISM EVOLVES 71 3.1 From the Old Terrorism to the New: The First World Trade Center Bombing 71 3.2 Adaptation—and Nonadaptation— ...in the Law Enforcement Community 73 3.3 . and in the Federal Aviation Administration 82 3.4 . and in the Intelligence Community 86 v Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page vi 3.5 . and in the State Department and the Defense Department 93 3.6 . and in the White House 98 3.7 . and in the Congress 102 4. RESPONSES TO AL QAEDA’S INITIAL ASSAULTS 108 4.1 Before the Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania 108 4.2 Crisis:August 1998 115 4.3 Diplomacy 121 4.4 Covert Action 126 4.5 Searching for Fresh Options 134 5. -

Angel Veneration and Christology a Study in Early Judaism and in the Christology of the Apocalypse of John

Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament • 2. Reihe Herausgegeben von Martin Hengel und Otfried Hofius 70 Angel Veneration and Christology A Study in Early Judaism and in the Christology of the Apocalypse of John by Loren T. Stuckenbruck ARTIBUS J.C.B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck) Tübingen Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Stuckenbruck, Loren T.: Angel veneration and christology : a study in early judaism and the christology of the Apocalypse of John / by Loren T. Stuckenbruck. - Tübingen : Mohr, 1995 (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament: Reihe 2 ; 70) ISBN 3-16-146303-X NE: Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament / 02 © 1995 by J. C. B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck), P.O. Box 2040, 72010 Tübingen. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher's written permission. This applies particularly to reproductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was printed by Guide-Druck in Tübingen on non-aging paper from Papierfabrik Niefern and bound by Heinr. Koch in Tübingen. Printed in Germany. ISSN 0340-9570 For my father, Earl Roy Stuckenbruck FOREWORD This book represents a slightly revised version of a dissertation sub- mitted to the faculty of Princeton Theological Seminary during September of 1993. I would first like to thank the committee readers of the dissertation, Professors J. Christiaan Beker, Ulrich W. Mauser and James H. Charlesworth (chair) each of whom has contributed to the unfolding of ideas contained here. I shall remain indebted to the learning, criticisms, and patient guid- ance they have given me. -

The Clash and Mass Media Messages from the Only Band That Matters

THE CLASH AND MASS MEDIA MESSAGES FROM THE ONLY BAND THAT MATTERS Sean Xavier Ahern A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2012 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Kristen Rudisill © 2012 Sean Xavier Ahern All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor This thesis analyzes the music of the British punk rock band The Clash through the use of media imagery in popular music in an effort to inform listeners of contemporary news items. I propose to look at the punk rock band The Clash not solely as a first wave English punk rock band but rather as a “news-giving” group as presented during their interview on the Tom Snyder show in 1981. I argue that the band’s use of communication metaphors and imagery in their songs and album art helped to communicate with their audience in a way that their contemporaries were unable to. Broken down into four chapters, I look at each of the major releases by the band in chronological order as they progressed from a London punk band to a globally known popular rock act. Viewing The Clash as a “news giving” punk rock band that inundated their lyrics, music videos and live performances with communication images, The Clash used their position as a popular act to inform their audience, asking them to question their surroundings and “know your rights.” iv For Pat and Zach Ahern Go Easy, Step Lightly, Stay Free. v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the help of many, many people. -

Buffy & Angel Watching Order

Start with: End with: BtVS 11 Welcome to the Hellmouth Angel 41 Deep Down BtVS 11 The Harvest Angel 41 Ground State BtVS 11 Witch Angel 41 The House Always Wins BtVS 11 Teacher's Pet Angel 41 Slouching Toward Bethlehem BtVS 12 Never Kill a Boy on the First Date Angel 42 Supersymmetry BtVS 12 The Pack Angel 42 Spin the Bottle BtVS 12 Angel Angel 42 Apocalypse, Nowish BtVS 12 I, Robot... You, Jane Angel 42 Habeas Corpses BtVS 13 The Puppet Show Angel 43 Long Day's Journey BtVS 13 Nightmares Angel 43 Awakening BtVS 13 Out of Mind, Out of Sight Angel 43 Soulless BtVS 13 Prophecy Girl Angel 44 Calvary Angel 44 Salvage BtVS 21 When She Was Bad Angel 44 Release BtVS 21 Some Assembly Required Angel 44 Orpheus BtVS 21 School Hard Angel 45 Players BtVS 21 Inca Mummy Girl Angel 45 Inside Out BtVS 22 Reptile Boy Angel 45 Shiny Happy People BtVS 22 Halloween Angel 45 The Magic Bullet BtVS 22 Lie to Me Angel 46 Sacrifice BtVS 22 The Dark Age Angel 46 Peace Out BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part One Angel 46 Home BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part Two BtVS 23 Ted BtVS 71 Lessons BtVS 23 Bad Eggs BtVS 71 Beneath You BtVS 24 Surprise BtVS 71 Same Time, Same Place BtVS 24 Innocence BtVS 71 Help BtVS 24 Phases BtVS 72 Selfless BtVS 24 Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered BtVS 72 Him BtVS 25 Passion BtVS 72 Conversations with Dead People BtVS 25 Killed by Death BtVS 72 Sleeper BtVS 25 I Only Have Eyes for You BtVS 73 Never Leave Me BtVS 25 Go Fish BtVS 73 Bring on the Night BtVS 26 Becoming, Part One BtVS 73 Showtime BtVS 26 Becoming, Part Two BtVS 74 Potential BtVS 74 -

RIVERSIDE COUNTY SUPERIOR COURT Southwest Justice Center – Department S-302

RIVERSIDE COUNTY SUPERIOR COURT Southwest Justice Center – Department S-302 Honorable Judge Angel Bermudez Unless contrary orders are made by written order, or on the record in open-court, the following orders apply to all cases assigned to Department S-302. References to “counsel” include any party who is self-represented. Failure to comply with the Court’s orders will subject parties/ counsel to sanctions, including sanctions pursuant to Code of Civil Procedure section 177.5. I. Ex Parte Applications 1. Ex parte applications are heard Monday through Friday at 8:30 am. The Court retains discretion to deny or grant an ex parte application without a hearing. 2. Requests to shorten time for notice, or to advance the hearing on a motion, will not be considered unless: (1) the motion has been filed with the Clerk’s Office, (2) a hearing date is on calendar, and (3) the appropriate filing fee has been paid (or a fee waiver obtained). II. Order to Show Cause Hearings 1. For any Order to Show Cause set against a party, a declaration must be filed no less than 5 court days prior to the hearing on the Order to Show Cause. Absent good cause for non-compliance of the filing of a declaration, failure to file a declaration will be construed as submitting on the violation for the noticed Order to Show Cause. III. Law and Motion 1. Pursuant to California Rules of Court, Rule 3.1308(a)(1), and Riverside Superior Court Local Rule 3316, tentative rulings are posted by 3:00 p.m., on the court-day immediately prior to the hearing at http://www.riverside.courts.ca.gov/tentativerulings.shtml. -

The Channel for Gay America? a Cultural Criticism of the Logo Channel’S Commercial

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 7-14-2008 The hC annel for Gay America? A Cultural Criticism of The Logo Channel’s Commercial Success on American Cable Television Michael Johnson Jr. University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Johnson, Michael Jr., "The hC annel for Gay America? A Cultural Criticism of The Logo Channel’s Commercial Success on American Cable Television" (2008). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/321 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Channel for Gay America? A Cultural Criticism of The Logo Channel’s Commercial Success on American Cable Television by Michael Johnson Jr. A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts Department of Humanities & American Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Elizabeth Bell, Ph.D. David Johnson, Ph.D. Sara Crawley, Ph.D. Date of Approval: July 14, 2008 Keywords: Advertisement, Programming, Queer, Sexuality, Activism © Copyright 2008, Michael Johnson Jr. Acknowledgements I can’t begin to express the depth of appreciation I have for everyone that has supported me throughout this short but exhausting intellectual endeavor. Thanks to David Johnson, Ph.D. & Sara Crawley, Ph.D.