Demantoid from Val Malenco, Italy: Review and Update

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

His Exhibition Features More Than Two Hundred Pieces of Jewelry Created Between 1880 and Around 1930. During This Vibrant Period

his exhibition features more than two hundred pieces of jewelry created between 1880 and around 1930. During this vibrant period, jewelry makers in the world’s centers of design created audacious new styles in response to growing industrialization and the changing Trole of women in society. Their “alternative” designs—boldly artistic, exquisitely detailed, hand wrought, and inspired by nature—became known as art jewelry. Maker & Muse explores five different regions of art jewelry design and fabrication: • Arts and Crafts in Britain • Art Nouveau in France • Jugendstil and Wiener Werkstätte in Germany and Austria • Louis Comfort Tiffany in New York • American Arts and Crafts in Chicago Examples by both men and women are displayed together to highlight commonalities while illustrating each maker’s distinctive approach. In regions where few women were present in the workshop, they remained unquestionably present in the mind of the designer. For not only were these pieces intended to accent the fashionable clothing and natural beauty of the wearer, women were also often represented within the work itself. Drawn from the extensive jewelry holdings of collector Richard H. Driehaus and other prominent public and private collections, this exhibition celebrates the beauty, craftsmanship and innovation of art jewelry. WHAT’S IN A LABEL? As you walk through the exhibition Maker and Muse: Women and Early Guest Labels were written by: Twentieth Century Art Jewelry you’ll Caito Amorose notice a number of blue labels hanging Jon Anderson from the cases. We’ve supplemented Jennifer Baron our typical museum labels for this Keith Belles exhibition by adding labels written by Nisha Blackwell local makers, social historians, and Melissa Frost fashion experts. -

Maker-Muse-Addendum-A.Pdf

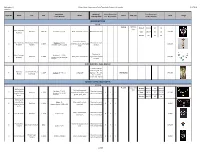

Addendum A Maker Muse: Women and Early Twentieth Century Art Jewelry 5/1/2018 Checklist Dimensions Mounting/ Mount Dimensions Case Dimensions Object No. Maker Title Date Media Case # Case Type Value Image H x W x D inches Installing Notes H x W x D inches H x W x D inches INTRODUCTION FC 1/6 FlatTable FC 1/6 Overall 50 1/4 36 20 Case Mrs. Charlotte 1 Pendant 1884-90 2 3/8 x 1 1/2 x 1/4 Gold, amethyst, enamel Mounted into deck - - - Case 38 1/4 36 20 $10,000 Newman Vitrine 12 36 12 Carved moonstone, Mrs. Charlotte Mary Queen of Scots Necklace: 20 1/2 Mounted on riser 2 c. 1890 amethyst, pearl, yellow gold - - - $16,500 Newman Pendant Pendant: 2 3/4 x 1 1/16 on deck chain Displayed in Mrs. Charlotte Necklace: L: 15 3/8 3 Necklace c. 1890 Gold, pearl, aquamarine original box directly - - - $19,000 Newman Pendant: 2 5/8 x 3 15/16 on deck INTRODUCTION - WALL DISPLAY Framed, D-Rings; wall hang; 68 - 72 Alphonse Sarah Bernhardt as 4 c. 1894 Framed: 96 x 41 x 2 Lithograph degrees F, 45 - 55% - - - Wall display $40,000 Mucha Gismonda RH, 5 - 7 foot candles (50 - 70 lux) BRITISH ARTS AND CRAFTS TC 1/10 TC 1/10 Large table Attributed to Overall 83 3/4 42 26 1/2 Gold, white enamel, case Jessie Marion Necklace: 5 11/16 Mounted on oval 5 Necklace c. 1905 chrysoberyl, peridot, green 8 6 1 Table 38 1/4 42 26 1/2 $11,000 King for Liberty Pendant: 2 x 13/16 riser on back deck garnet, pearl, opal & Co. -

LMHC Information Sheet # 8 Gemstones Where Colour Authenticity Is Undetermined

LMHC Standardised Gemmological Report Wording (version 5; December 2014) LMHC Information Sheet # 8 Gemstones where colour authenticity is undetermined Members of the Laboratory Manual Harmonisation Committee (LMHC) have standardised the wording they use to describe cases where colour authenticity is undetermined. These situations typically apply to beryl, demantoid garnet, quartz, spodumene (kunzite), topaz, tourmaline, zircon, zoisite (tanzanite), etc. Gemstones which are commonly heated and/or irradiated, but whose treatment, or lack thereof, is typically not determinable or has not been determined, shall be described as, Identification: Species: (Natural)1 [Species]2 Variety: [Colour3, Variety4] Further information5: [Gemstone]2 is commonly heated and/or irradiated6 (to improve or change the colour)1 and/or Colour authenticity is currently undeterminable, or Colour authenticity has not been determined. 1 wording and text in parenthesis is optional 2 Insert the recognized species name 3 Insert colour when appropriate 4 Insert the recognized variety name 5 This information may be on the report or in an attachment 6 Use heated and/or irradiated as appropriate © Laboratory Manual Harmonisation Committee. This document may be freely copied and distributed as long as it is reproduced in its entirety, complete with this copyright statement. Any other reproduction, translation or abstracting is prohibited without the express written consent of the Laboratory Manual Harmonisation Committee. All rights jointly reserved by: Central Gem Laboratory CGL (Japan), CISGEM Laboratory (Italy), DSEF German Gem Lab (Germany), GIA Laboratory (USA), Gem and Jewelry Institute of Thailand GIT (Thailand), Gübelin Gem Lab Ltd. (Switzerland), Swiss Gemmological Institute - SSEF (Switzerland) LMHC - IS 8: Page 1 of 1 . -

Precious Stones Arthur Herbert

L'-RARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA DICHROISM AND SPECTRA OF PRECIOUS STONES SAPPHIRE RUBY EMERALD PERIDOT BROWN TOURMALINE BROWN TOURMALINE ANDALUSITE ALEXANDRITE ALMANDINE GARNET a B C D E b ZIRCON a B c D BOARD OF EDUCATION, SOUTH KENSINGTON, VICTORIA AND ALBERT MUSEUM. PRECIOUS STONES CONSIDERED IN THEIR SCIENTIFIC AND ARTISTIC RELATIONS WITH A CATALOGUE OF THE TOWNSHEND COLLECTION BY A. H. CHURCH, F.R.S.. M.A., D.Sc., F.S.A., Professov of Chemistry in the Royal Academy of Arts in London. NEW EDITION. LONDON : PRINTED FOR HIS MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE, BY WYMAN & SONS, LIMITED, FETTER LANE, E.C. 1905. Price Is. 6d. ; in Cloth, 2s. 3d. At Museum 1/6 EARTH SCIENCES t'BRARY CONTENTS. Page PREFACE ... v PREFACE TO FIRST EDITION . viii BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTES . CHAPTER I. DEFINITION OF PRECIOUS STONES . CHAPTER II. PROPERTIES AND DISCRIMINATION OF PRECIOUS STONES. CHAPTER III. 25 CUTTING AND FASHIONING PRECIOUS STONES . CHAPTER IV. ARTISTIC EMPLOYMENT OF PRECIOUS STONES CHAPTER V. ARTIFICIAL FORMATION OF PRECIOUS STONES ... .48 CHAPTER VI. IMITATIONS OF PRECIOUS STONES . .51 8445. 1000 Wt. 29306. 5/05. Wy. & S. 3407r a iv PRECIOUS STONES. CHAPTER VII. Page - DESCRIPTIONS OF PRECIOUS STONES . , .54 and 61 67 Tur- Diamond, 54 ; Corundum, Sapphire Ruby, ; Spinel, ; 75 78 ; 85 ; quoise, 70 ; Topaz, 72 ; Tourmaline, ; Garnet, Peridot, 90 91 92 Beryl and Emerald, 87 ; Chrysoberyl, ; Phenakite, ; Euclase, ; 96 96 Zircon, 92 ; Spodumene,'96 ; Hiddenite, ; Kunzite, ; Opal, 97 ; 102 lolite 103 104 Labrador- Quartz, 99 ; lapis-lazuli, ; ; Crocidolite, ; 105 106 106 106 ite, 105 ; Moonstone, ; Sunstone, ; Obsidian, ; Epidote, ; 108 Axinite, 107 ; Sphene, 107 ; Cossiterite, 107 ; Diopside, ; Apophyllite, 108; Andalusite, 109; Jade and Jadeite, 110; Pyrites, 111; Haematite, 112 ; Amber, 112 ; Jet, 113; Malachite, 113; 114 Lumachella, 114; Pearl, ; Coral, 117. -

Fine Jewelry

FINE JEWELRY Wednesday, March 3, 2021 DOYLE.COM FINE JEWELRY AUCTION Wednesday, March 3, 2021 at 10am Eastern VIEWINGS BY APPOINTMENT Please contact Laura Chambers to schedule your appointment: [email protected] Safety protocols will be in place with limited capacity. Please maintain social distance during your visit. LOCATION Doyle Auctioneers & Appraisers 175 East 87th Street New York, NY 10128 212-427-2730 This Gallery Guide was created on 2-18-21 Please see addendum for any changes The most up to date information is available On DOYLE.COM Sale Info View Lots and Place Bids Doyle New York 1 7 Bulgari Pair of Gold 'Parentesi' Earrings Long Gold, Peridot and Blue Topaz Briolette 18 kt., of scrolled geometric design, signed Chain Necklace Bulgari, ap. 11 dwts. 14 kt., composed of 174 collet-set round peridots C ap. 30.50 cts., joined by circle links, suspending $700-900 at intervals 42 blue topaz briolettes. Length 69 1/2 inches. C $1,200-1,800 2 8 Cartier Gold and Diamond 'Panthère' Bulgari Gold, Peridot and Aquamarine Wristwatch 'Doppio Baccellato' Ring 18 kt., quartz, centering a square off-white dial 18 kt., centering one cushion-shaped peridot ap. with black Roman numerals, inner track indicator 3.00 cts., and one cushion-shaped aquamarine and blued steel hands, within a single-cut ap. 3.00 cts., within a ribbed mount, signed diamond-set bezel, with inverted diamond crown, Bulgari, no. B2342, partially obscured, ap. 14.4 dia. ap. 26 x 22 mm., completed by a five-row dwts. Size 6, with bumpers. -

Information Circular

Information Circular Pakistan.... Demuntoid Garnet- ll/ith enormous gem potentiul Rediscovered!! Pakistan - better known as a producer of some fine Demantoid, one most rare varieties of quality of emeralds up till few years back, but now of the Garnet group has been re-discovered in the Urals in the recent past the gem and mineral world trade in Russia and is now encountered in the market have witnessed some extremely fine quality of much frequenth/ than ever other gemstones from the region. Some of the before. minerals make the country / region prominent in Demantoid, the terrn is derived from the Dutch the mineral world. warddemant, meaning diamond. Demantoid was first discovered in the mid to late 1800s in Russia Pakistan is bounded by Afghanistan in the during the reign of Czar Alexander II. The newly nofthwest, while India in the east and Iran in the discovered gemstone $/est. The northern and northwestern part of made an impressive showing, enhancing the Russian Pakistan produces the maximum number of cultural life of nobles. gemstones. Three world famous ranges Demantoids were used by Karl Faberge' in combination with enamel gold his jewel Hindkush, Himalayas and Karakoram, enclose the and in creations for royal treasures. gem producing region. Demantoid belongs to lhe andradite a Sorne of the well- known gem species supplied to species calcium iron silicate; CarFe,(SiO.),. The stones the world market from the region includes aquamarine, topaz, Peridot, ruby, emerald, range in colour from pale green to yellowish green green. amethyst, morganite, Zoisite, spinel, sphene, to emerald The colour of Demantoid tou rma line, spessartite and demantoid. -

Chemometric Modeling of Trace Element Data for Origin Determination of Demantoid Garnets

minerals Article Chemometric Modeling of Trace Element Data for Origin Determination of Demantoid Garnets Stefan G. Bindereif 1, Felix Rüll 1 , Stephan Schwarzinger 1 and Clemens Schwarzinger 2,* 1 North Bavarian NMR-Centre, University of Bayreuth, 95447 Bayreuth, Germany; [email protected] (S.G.B.); [email protected] (F.R.); [email protected] (S.S.) 2 Institute for Chemical Technology of Organic Materials, Johannes Kepler Univeristy Linz, 4040 Linz, Austria * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +43-732-2468-9011 Received: 21 October 2020; Accepted: 22 November 2020; Published: 24 November 2020 Abstract: The determination of country of origin poses a common problem in the appraisal of gemstones and is in many cases still based on the observation of inclusions and growth features of a gem, whereas chemical analysis is only done by major labs. We have used Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry to analyze the trace element profiles of demantoid garnets from six different countries and identified a set of six elements, which are magnesium, aluminum, titanium, vanadium, chromium, and manganese, that are necessary to assign the mining regions with a good certainty. By using the logarithms of the trace element concentrations and subjecting them to chemometric modeling, we were able to separate the demantoids originating from Russia, Pakistan, Namibia, Iran, and Madagascar very well, leaving only Italy with some uncertainty. Results are presented for an “all origins” model as well as pair-wise comparison of two locations at a time, which lead to even better results. Keywords: multivariate statistics; chemometrics; origin determination; garnets; demantoid; LA-ICP-MS 1. -

Trapiche Tourmaline

The Journal of Gemmology2011 / Volume 32 / Nos. 5/8 Trapiche tourmaline The Gemmological Association of Great Britain The Journal of Gemmology / 2011 / Volume 32 / No. 5–8 The Gemmological Association of Great Britain 27 Greville Street, London EC1N 8TN, UK T: +44 (0)20 7404 3334 F: +44 (0)20 7404 8843 E: [email protected] W: www.gem-a.com Registered Charity No. 1109555 Registered office: Palladium House, 1–4 Argyll Street, London W1F 7LD President: Prof. A. H. Rankin Vice-Presidents: N. W. Deeks, R. A. Howie, E. A. Jobbins, M. J. O'Donoghue Honorary Fellows: R. A. Howie Honorary Life Members: H. Bank, D. J. Callaghan, T. M. J. Davidson, J. S. Harris, J. A. W. Hodgkinson, E. A. Jobbins, J. I. Koivula, M. J. O’Donoghue, C. M. Ou Yang, E. Stern, I. Thomson, V. P. Watson, C. H. Winter Chief Executive Officer: J. M. Ogden Council: J. Riley – Chairman, S. Collins, B. Jackson, S. Jordan, C. J. E. Oldershaw, L. Palmer, R. M. Slater Members’ Audit Committee: A. J. Allnutt, P. Dwyer-Hickey, E. Gleave, J. Greatwood, G. M. Green, K. Gregory, J. Kalischer Branch Chairmen: Midlands – P. Phillips, North East – M. Houghton, North West – J. Riley, South East – V. Wetten, South West – R. M. Slater The Journal of Gemmology Editor: Dr R. R. Harding Deputy Editor: E. A. Skalwold Assistant Editor: M. J. O’Donoghue Associate Editors: Dr A. J. Allnutt (Chislehurst), Dr C. E. S. Arps (Leiden), G. Bosshart (Horgen), Prof. A. T. Collins (London), J. Finlayson (Stoke on Trent), Dr J. -

Tiffany Colored Gemstones | 1

Tiffany Colored Gemstones | 1 Tiffany has a longstanding legacy as a purveyor of the world’s most exceptional and rare colored gemstones, introducing gemstones that had never been used in jewelry until Tiffany popularized them. While many jewelers showcase rubies, emeralds and sapphires, Tiffany is proud to include a wide range of colored gemstones in its designs, encompassing the full spectrum of color. Colored gemstones have been integral to establishing Tiffany’s reputation as a world- renowned jeweler. Prior to the mid-19th century, colored gemstones were rarely used in American jewelry. This all changed in 1876, when a young gemologist, Dr. George Frederick Kunz (1856–1932), sold an exceptional tourmaline to founder Charles Lewis Tiffany (1812–1902). Soon after, Dr. Kunz joined the company and embarked on a lifelong quest for the most extraordinary gemstones for Tiffany’s clientele. The treasures introduced by this intrepid globetrotter constituted the world’s greatest collection of gemstones, including exotic yellow beryl from Sri Lanka (Ceylon), green demantoid garnets from Russia’s Ural Mountains and ocean-blue aquamarines from Brazil. Kunz was equally passionate about American gemstones, adding Montana sapphires, Maine tourmalines, and garnets and topazes from Utah to Tiffany’s burgeoning vault. In 1902, a lilac pink stone that had been found in California was delivered to Kunz. The stone was a variety of spodumene, a newly discovered gemstone. A fellow gemologist named the stone “kunzite” after the man who made beautiful gemstones his lifelong passion. This stone is the first of several Tiffany legacy gemstones that the luxury house proudly introduced to the world. -

Western Mineral Resources

Garnet—An Essential Industrial Mineral and January’s Birthstone Photograph of a mineral arnet is one of the most specimen containing large G common minerals in the crystals of the garnet world. Occurring in almost any mineral spessartine (red), showing the distinctive color, it is most widely known “euhedral isometric” for its beauty as a gem stone. crystal form of garnet. Used Because of its hardness and since ancient times for other properties, garnet is also an jewelry, the first industrial use of garnet was prob- essential industrial mineral used ably in coated sandpaper in abrasive products, non-slip manufactured in the United surfaces, and filtration. To help States by Henry Hudson Barton in 1878. The United manage our Nation’s resources of States currently consumes such essential minerals, the U.S. about 16 percent of the Geological Survey (USGS) pro- global production of indus- vides crucial data and scientific trial garnet. (Copyrighted photo by Stan Celestian/ information to industry, policy- courtesy of Glendale Com- makers, and the public. munity College). Garnet as a Gem Stone in 1878. Garnet is an important industrial ing aluminum and other soft metals for mineral because it is relatively hard, rating 6 use in aircraft and ships; deburring welds Garnet is familiar to many people as to about 8 on the “Mohs scale of hardness,” and grinding and polishing optical lenses; January’s birthstone and as the New York where diamond is the hardest at 10. Conse- producing high-quality, scratch-free semi- State gem stone. It has been used as a gem quently, garnet is an excellent abrasive for conductor materials; finishing hard rubber, stone since prehistoric times. -

The Gemstone Book

© CIBJO 2020 All rights reserved GEMSTONE COMMISSION 2020 - 1 2020-1 2020-12-1 CIBJO/Coloured Stone Commission The Gemstone Book CIBJO standard E © CIBJO 2020. All rights reserved COLOURED STONE COMMISSION 2020-1 Foreword .................................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ............................................................................................................................... vi 1. Scope ................................................................................................................................. 8 2. Normative references .......................................................................................................... 8 3. Classification of materials .................................................................................................... 9 3.1. Natural materials ........................................................................................................... 9 Only materials that have been formed completely by nature without human interference/intervention qualify as “natural” within this standard. ........................................... 9 3.1.1. Gemstones ................................................................................................................................... 9 3.2. Artificial products ........................................................................................................... 9 3.2.1. Artificial products with gemstone components -

SSEF Facette 22 «Undisclosed Natural Diamonds in a Parcel Of

INTERNATIONAL ISSUE N0.22, FEBRUARY 2016 Swiss Gemmological Institute SSEF THE SCIENCE OF GEMSTONE TESTING® Aeschengraben 26 CH-4051 Basel Switzerland Tel.: +41 61 262 06 40 Fax: +41 61 262 06 41 [email protected] www.ssef.ch SSEF RELOCATION / COLOUR TERMS / NEW SAPPHIRE SOURCES DIAMOND RESEARCH / SPINEL / PEARL ANALYSIS / SSEF AT AUCTION SSEF COURSES / SSEF IN ASIA / ON-SITE TESTING EDITORIAL Dear Reader It is for me a great pleasure to present you the 22nd issue of the SSEF Having seen in the past few months again the most outstanding and Facette, summarizing all major achievements the Swiss Gemmological intriguing gems, pearls, and jewels offered in the trade and at auction Institute SSEF has accomplished in recent months, but also and more worldwide, we at SSEF feel very privileged, as we do not only see and importantly, to inform you about our latest research focussed on touch these items, but are able to analyse them meticulously with our diamonds, coloured gems, and pearls. analytical equipment to uncover their most hidden secrets of beauty and to challenge our scientific curiosity. Our annual magazine this time is a special issue, as it not only covers the past few months, but actually two years since the last SSEF Facette. In this spirit I wish you a very successful and exciting 2016 with lots The reason for this one year interruption in publishing was that we were of business opportunities despite the rather difficult current market very busy end of last year with the relocation of the SSEF laboratory situation. into new premises.