Reading Raymond Pettibon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cartographic Perspectives Information Society 1

Number 53, Winterjournal 2006 of the Northcartographic American Cartographic perspectives Information Society 1 cartographic perspectives Number 53, Winter 2006 in this issue Letter from the Editor INTRODUCTION Art and Mapping: An Introduction 4 Denis Cosgrove Dear Members of NACIS, FEATURED ARTICLES Welcome to CP53, the first issue of Map Art 5 Cartographic Perspectives in 2006. I Denis Wood plan to be brief with my column as there is plenty to read on the fol- Interpreting Map Art with a Perspective Learned from 15 lowing pages. This is an important J.M. Blaut issue on Art and Cartography that Dalia Varanka was spearheaded about a year ago by Denis Wood and John Krygier. Art-Machines, Body-Ovens and Map-Recipes: Entries for a 24 It’s importance lies in the fact that Psychogeographic Dictionary nothing like this has ever been kanarinka published in an academic journal. Ever. To punctuate it’s importance, Jake Barton’s Performance Maps: An Essay 41 let me share a view of one of the John Krygier reviewers of this volume: CARTOGRAPHIC TECHNIQUES …publish these articles. Nothing Cartographic Design on Maine’s Appalachian Trail 51 more, nothing less. Publish them. Michael Hermann and Eugene Carpentier III They are exciting. They are interest- ing: they stimulate thought! …They CARTOGRAPHIC COLLECTIONS are the first essays I’ve read (other Illinois Historical Aerial Photography Digital Archive Keeps 56 than exhibition catalogs) that actu- Growing ally try — and succeed — to come to Arlyn Booth and Tom Huber terms with the intersections of maps and art, that replace the old formula REVIEWS of maps in/as art, art in/as maps by Historical Atlas of Central America 58 Reviewed by Mary L. -

RAYMOND PETTIBON to Wit

519 West 19th Street Fax 212 727 2072 David Zwirner New York, NY 10011 Telephone 212 727 2070 For immediate release RAYMOND PETTIBON To Wit September 12 – October 26, 2013 Opening reception: Thursday, September 12, 6 – 8 PM David Zwirner is pleased to present an exhibition of new works by Raymond Pettibon, on view at the gallery’s 519 West 19th Street space in New York. It marks the artist’s ninth solo exhibition with David Zwirner since joining the gallery in 1995. Pettibon’s work embraces a wide spectrum of American “high” and “low” culture, from the deviations of marginal youth to art history, literature, sports, religion, politics, and sexuality. Taking their points of departure in the Southern California punk-rock culture of the late 1970s and 1980s and the “do-it-yourself” aesthetic of album covers, comics, concert flyers, and fanzines that characterized the movement, his drawings have come to occupy their own genre of potent and dynamic artistic commentary. To Wit presents a wide range of drawings and collages unified by their bold, vivid lines and striking compositions. Fragments from American society have been distilled into key images, which often incorporate texts of varying length, from one word to several paragraphs. The selection of texts, spanning a broad array of influences from popular media to Marcel Proust, William Faulkner, Henry James, Gustave Flaubert, and the Bible, relate both rhythmically and narratively to the visual content of his drawings, although their relationship may not always be immediately apparent. No Title (Route 69, follow…), 2013 Collage, ink, and gouache on paper 27 ¼ x 17 inches (69.2 x 43.2 cm) Defined as “namely” or “that is to say,” to wit originally meant “to know” (from the Middle English, “to witen”). -

William Gropper's

US $25 The Global Journal of Prints and Ideas March – April 2014 Volume 3, Number 6 Artists Against Racism and the War, 1968 • Blacklisted: William Gropper • AIDS Activism and the Geldzahler Portfolio Zarina: Paper and Partition • Social Paper • Hieronymus Cock • Prix de Print • Directory 2014 • ≤100 • News New lithographs by Charles Arnoldi Jesse (2013). Five-color lithograph, 13 ¾ x 12 inches, edition of 20. see more new lithographs by Arnoldi at tamarind.unm.edu March – April 2014 In This Issue Volume 3, Number 6 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Fierce Barbarians Associate Publisher Miguel de Baca 4 Julie Bernatz The Geldzahler Portfoio as AIDS Activism Managing Editor John Murphy 10 Dana Johnson Blacklisted: William Gropper’s Capriccios Makeda Best 15 News Editor Twenty-Five Artists Against Racism Isabella Kendrick and the War, 1968 Manuscript Editor Prudence Crowther Shaurya Kumar 20 Zarina: Paper and Partition Online Columnist Jessica Cochran & Melissa Potter 25 Sarah Kirk Hanley Papermaking and Social Action Design Director Prix de Print, No. 4 26 Skip Langer Richard H. Axsom Annu Vertanen: Breathing Touch Editorial Associate Michael Ferut Treasures from the Vault 28 Rowan Bain Ester Hernandez, Sun Mad Reviews Britany Salsbury 30 Programs for the Théâtre de l’Oeuvre Kate McCrickard 33 Hieronymus Cock Aux Quatre Vents Alexandra Onuf 36 Hieronymus Cock: The Renaissance Reconceived Jill Bugajski 40 The Art of Influence: Asian Propaganda Sarah Andress 42 Nicola López: Big Eye Susan Tallman 43 Jane Hammond: Snapshot Odyssey On the Cover: Annu Vertanen, detail of Breathing Touch (2012–13), woodcut on Maru Rojas 44 multiple sheets of machine-made Kozo papers, Peter Blake: Found Art: Eggs Unique image. -

IRINA KORINA: “I Am Interested in How to Make Work That Joins Memories, Nostalgia, and Architecture

SUMMER 2017 EXHIBITION SEASON IRINA KORINA: “I am interested in how to make work that joins memories, nostalgia, and architecture. For me, ultimately, Congo Art Works: it’s about a Popular Painting transformation /PAGE 4 of the hierarchy Raymond Pettibon. The Cloud of of values.” Misreading /PAGE 6 David Adjaye: Form, Heft, Material /PAGE 12 Kholin and Sapgir. Manuscripts /PAGE 14 Bone Music. An Interview with Stephen Coates /PAGE 15 Irina Korina: The Tail Wags the Comet /PAGE 3 www.garagemca.org 2 EDITORIAL Welcome! Dear Garage visitor, Dasha Zhukova, Anton Belov, Founder, Garage Museum Director, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art of Contemporary Art his is the third edition of Garage Gazette, an hether you are at Garage for the first time to the collector and chronicler of Moscow underground annual publication which provides information or a regular visitor, I’d like to welcome art Leonid Talochkin and the artist Viktor Pivovarov. The about the Museum’s summer season and gives you to the Museum, which has become an Archive is accessible to the general public—we even offer a sneak preview of what’s to come in fall. First, established landmark in Gorky Park since free tours—and we continue to curate exhibitions based Tthough, I would like to look back to the start of 2017 Wopening here two years ago. We are really excited about on our holdings. This summer you can see Kholin and and Garage Triennial of Russian Contemporary Art, our summer season and hope that you will be too. Sapgir. Manuscripts, which looks at the work of two lead- which brought together works by over 60 artists and Since March, we have presented a specially-commis- ing poets of the Moscow underground with strong links to artist groups from across the country. -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Arts and Architecture PLANTAE, ANIMALIA, FUNGI: TRANSFORMATIONS OF NATURAL HISTORY IN CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN ART A Dissertation in Art History by Alissa Walls Mazow © 2009 Alissa Walls Mazow Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2009 The Dissertation of Alissa Walls Mazow was reviewed and approved* by the following: Sarah K. Rich Associate Professor of Art History Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Brian A. Curran Associate Professor of Art History Richard M. Doyle Professor of English, Science, Technology and Society, and Information Science and Technology Nancy Locke Associate Professor of Art History Craig Zabel Associate Professor of Art History Head of the Department of Art History *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ii Abstract This dissertation examines the ways that five contemporary artists—Mark Dion (b. 1961), Fred Tomaselli (b. 1956), Walton Ford (b. 1960), Roxy Paine (b. 1966) and Cy Twombly (b. 1928)—have adopted the visual traditions and theoretical formulations of historical natural history to explore longstanding relationships between “nature” and “culture” and begin new dialogues about emerging paradigms, wherein plants, animals and fungi engage in ecologically-conscious dialogues. Using motifs such as curiosity cabinets and systems of taxonomy, these artists demonstrate a growing interest in the paradigms of natural history. For these practitioners natural history operates within the realm of history, memory and mythology, inspiring them to make works that examine a scientific paradigm long thought to be obsolete. This study, which itself takes on the form of a curiosity cabinet, identifies three points of consonance among these artists. -

Punk Is Dead” Catalog Includes, the SST Records the Inventory Representing the “Punk Is Collection, C

2016 PUNK IS DEAD Lux Mentis, Booksellers Lux Mentis Booksellers specializes in fine press, artist books, first editions, Punk rock evolved over several and esoterica with a particular emphasis generations and manifestations of youth on challenging and unusual materials. culture beginning in the 1970s. Even after 40 years, punk subculture still We actively collaborate with archives demonstrates the capability to influence and special collections libraries to meet successive contemporary elements of the research and collecting needs of art, music, and fashion regardless of its public learning institutions, private, original intention to lambast conformity. independent libraries and collections with primary sources. Selected inventory in the “Punk is Dead” catalog includes, the SST Records The inventory representing the “Punk is Collection, c. 1979-1996; original Dead” collection is a retrospective artwork from famed punk artist, selection of critical primary source Raymond Pettibon; correspondence materials documenting the punk rock from Gordon Gano, original member of movement of the 1970s-1990s. The the Violent Femmes; and several unique collection illustrates the profound fanzine and alternative publications. subculture of punk from an artistic and politically fueled era from Los Angeles, Lux Mentis regularly features and New York, and London. showcases punk culture related materials at major ABAA book fairs and Please contact us for an appointment or continues to cultivate the acquisition of with questions regarding the inventory. subculture materials for research and collection development purposes. 110 Marginal Way #777 Portland, ME 04101 Member: ILAB/ABAA T. 207.329.1469 Email: [email protected] Front cover image: From the SST [email protected] Records Collection, detail of “Outcry” Web: http://www.luxmentis.com magazine Blog: http://www.asideofbooks.com Cataloged created by Kim Schwenk and edited by Ian Kahn 2 Ginn, Greg, Pettibon, Raymond, et al. -

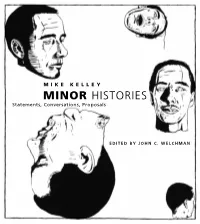

MINOR HISTORIES Statements, Conversations, Proposals MIKE KELLEY Edited by John C

KELLEY MINOR HISTORIES Statements, Conversations, Proposals MIKE KELLEY edited by John C. Welchman What John C. Welchman calls the “blazing network of focused conflations” from which Mike Kelley’s styles are generated is on display in all its diversity in this second volume of his writings. The first volume, Foul Perfection, contained thematic essays and writings about other artists; this collection concentrates on Kelley’s own work, ranging from texts in “voices” that grew out of scripts for performance pieces to expository critical and autobiographical writings. Minor Histories organizes Kelley’s writings into five sections. “Statements” consists of twenty pieces produced MINOR between 1984 and 2002 (most of which were written to accompany exhibitions), including “Ajax,” which draws on MIKE KELLEY Homeric epic, Colgate-Palmolive advertising, and Longinus to present its eponymous hero; “Some Aesthetic High Points,” an exercise in autobiography that counters the standard artist bio included in catalogs and press releases; and a sequence of “creative writings” that use mass cultural tropes in concert with high art mannerisms—approximating in prose the visu- MINOR HISTORIES al styles that characterize Kelley’s artwork. “Video Statements and Proposals” are introductions to videos made by Kelley and other artists, including Paul McCarthy and Bob Flanagan and Sheree Rose. “Image-Texts” offers writings that accom- Statements, Conversations, Proposals pany or are part of artworks and installations. This section includes “A Stopgap Measure,” Kelley’s zestful millennial essay in social satire, and “Meet John Doe,” a collage of appropriated texts. The section “Architecture” features a discussion of Kelley’s Educational Complex (1995) and an interview in which he reflects on the role of architecture in his work. -

Are Your Motives Pure? Raymond Pettibon Surfers 1985-2013 April 3 - May 17, 2014 Opening: Thursday, April 3Rd, 6:00 - 9:00 Pm

Are Your Motives Pure? Raymond Pettibon Surfers 1985-2013 April 3 - May 17, 2014 Opening: Thursday, April 3rd, 6:00 - 9:00 pm Venus Over Manhattan 980 Madison Avenue New York, NY 10075 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: VENUS OVER MANHATTAN PRESENTS THE FIRST EXHIBITION DEVOTED TO THE “SURFER PAINTINGS” OF RAYMOND PETTIBON (New York, NY) – Since the 1970s, Los Angeles-based artist Raymond Pettibon has been metabolizing America – its history, literature, sports, religion, politics, and sexuality – in a barrage of drawings and paintings in a style born of comic books and the “do-it-yourself” aesthetic of Southern California punk rock album-covers, concert flyers, and fanzines. Limning a dizzying array of topics with his distinctive combinations of image and text, Pettibon has created a vocabulary of symbols that reappear consistently if enigmatically across his oeuvre. These range from baseball players, vixens, light bulbs, and railway trains, to the cartoon character Gumby and infamous murderer Charles Manson: pet themes repeated and reworked in a classically American combination of abundance and monotony. But the most poetic and revealing of Pettibon’s symbols may be the surfer, the solitary longboarder challenging a massive wave. In his “surfer paintings,” viewers find the lyrical heart of Pettibon’s work and ride along with a counter-culture existentialist hero who perhaps is the artist’s nearest proxy. Beginning April 3, 2014, Venus Over Manhattan will present the first exhibition ever organized to focus exclusively on Raymond Pettibon’s ‘surfer paintings.’ Are Your Motives Pure? Raymond Pettibon Surfers 1985-2013, brings together forty works spanning a quarter century of the artist’s career, on loan from important collections. -

How Much Art Can You Take?

HOW MUCH ART CAN YOU TAKE? I go to an art museum It’s more like a mausoleum — Really Red, “No Art In Houston” The term “Hardcore art” is an oxymoron. Hardcore types fancied themselves dismissive of all art. Theirs was an essentially undecorated, unadorned world. Yet the term will be useful herein. Hardcore communicated through low-tech graphics that read as art. Appropriated shards of advertising and photojournalism comprised stark stylistic hodge-podges announcing shows and records. The graphics, like the music, challenged brain-dead consumers, Reagan’s government, and multi- national corporations. WINSTON SMITH (artist): There was a drive to get away from fine, finished-looking work that looked like it came out of a record company art department. Instead of creating overblown work that makes the individual feel smaller, Hardcore made the individual feel included. It was not a glamour trip; the artwork was chaotic and spontaneous. Hardcore kids dismissed art as a bourgeois indulgence. Of course enough of it seeped into the mix to encourage an identifiable art style fusing collage, illustration and typography, almost always in black-and-white. A tribal iconography manifested itself in distinct record covers and gig flyers, with a politically incorrectness proclaiming, “This is hard-core.” GLENN DANZIG (The Misfits): It had a definite look and style — there’s an art to brutality. That’s why Example of Hardcore era art certain boxers are better than others — there’s an art. Flyer for Wasted Youth Reagan’s In album, 1981 Collection of the author Hardcore fans claimed to hate anything with “art school” pretense or pseudo-intellectualism, and felt “arty” types lacked intensity. -

Download Code

Antiquariat Querido – Frank Hermann Visual Vinyl Kunst nach 1945 | Fotografie · Architektur · Design · Kunst Die kalifornische Punk-Szene der 1970er-Jahre war ein Schmelztiegel aus Musik, Krea- tivität und Drogen. Wer nicht durch Selbstmord oder eine Überdosis starb, richtete sich Roßstraße 13 · 40476 Düsseldorf | Blücherstraße 7 · 40477 Düsseldorf nicht selten durch die kontinuierliche Zerstörung der eigenen Existenz zu Grunde. Einer, der die wilde Phase jener Jahre bis heute überlebt hat, ist Raymond Pettibon, der durch seinen legendären Coverentwurf für die Punkband Black Flag schon früh zur Legende Tel. 00 49 211 15969601 wurde – weit über die Grenzen der Punk-Szene hinaus. Fax 00 49 211 15969602 Pettibons Entwurf wurde durch seine Radikalität zum Wegweiser für nachfolgende Ge- nerationen von Künstlern, die sich mit der Aufgabe konfrontiert sahen, den formalen Mi + Do 11.00 - 19.00 Uhr und nach Vereinbarung gestalterischen Grenzen eines Plattencovers mit kraftvollen und prägenden Designs ent- gegenzutreten. [email protected] Visual Vinyl liefert erstmals einen umfassenden Überblick über diese „Künstler-Cover“. www.antiquariat-querido.de Als Fundus dient das umfangreiche Archiv des Niederländers Jan van Toorn – einer der umtriebigsten Sammler und größten Kenner auf diesem Gebiet. Die Bandbreite der vorgestellten Arbeiten reicht von surrealistischen Entwürfen von Salvador Dalí über Co- Stadtsparkasse Düsseldorf > SWIFT-BIC: DUSSDEDDXXX ver von Pop-Art-Größen wie Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg oder IBAN: DE 38 3005 0110 0010 1833 66 Jean-Michel Basquiat bis hin zu Arbeiten der Wiener Aktionisten und aktuellen Werken USt-ID-Nr. DE 171/397705 > StNr. 105/5108/1390 von Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst, Banksy oder Ai Weiwei. -

Raymond Pettibon Biography

RAYMOND PETTIBON BIOGRAPHY Born in Tucson, AZ, 1957. Lives and works in New York, NY. Education: B.A., University of California, Los Angeles, CA, 1977 Selected Solo Exhibitions: 2020 “Tennis Elbow: Raymond Pettibon,” The Journal Gallery, New York, NY, November 6 – December 2, 2020 “Raymond Pettibon: Pacific Ocean Pop,” Regen Projects, Los Angeles, CA, September 12 – October 31, 2020 2019 “Raymond Pettibon: And What is Drawing For?” Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Tel Aviv, Israel, November 21, 2019 – July 4, 2020; catalogue “Raymond Pettibon: Frenchette,” David Zwirner, Paris, France, October 16 – November 23, 2019 “Daumier – Pettibon,” Kunst Museum Winterthur, Reinhart am Stadtgarten, Winterthur, Switzerland, March 2 – August 4, 2019; catalogue 2018 “Raymond Pettibon: … No hugs coming,” Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin, Germany, April 27 – June 2, 2018 “Raymond Pettibon: A Selection by Dan Graham,” Galleri Nicolai Wallner, Copenhagen, Denmark, January 26 – March 17, 2018 2017 “Raymond Pettibon: The Cloud of Misreading,” Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, Moscow, Russia, June 7 – August 13, 2017; catalogue “Raymond Pettibon: TH 'EXPLOSIYV SHOYRT T,” David Zwirner, New York, NY, April 29 – June 24, 2017 “Raymond Pettibon: A Pen of All Work,” New Museum, New York, NY, February 8 – April 9, 2017; travels to Bonnefanten, Maastricht, Netherlands, June 2 – October 29, 2017; catalogue 2016 “Marcel Dzama and Raymond Pettibon: Let us compare mythologies,” David Zwirner, London, UK, October 5 – November 12, 2016 “Bakersfield to Barstow to Cucamonga to Hollywooyd,” Sadie Coles HQ, London, UK, June 25 – August 13, 2016 “Raymond Pettibon – Homo Americanus,” Deichtorhallen Hamburg/Sammlung Falckenberg, Hamburg, Germany, February 28 – September 11, 2016; travels to Museum der Moderne Salzburg, Salzburg, Austria, November 19, 2016 – February 12, 2017; catalogue “Marcel Dzama and Raymond Pettibon: Forgetting the Hand,” David Zwirner, New York, NY, January 14 – February 20, 2016; limited edition zine 2015 “Home and Away. -

Artist Resources – Raymond Pettibon (American, B. 1957)

Artist Resources – Raymond Pettibon (American, b. 1957) Pettibon at David Zwirner Pettibon at Regen Projects Pettibon’s artist books, combining original images and text quotations, were on display in a 1993 exhibition at Regen Projects. The show also dissected Pettibon’s book-making process and displayed pages as individual artworks on the gallery walls. In 1998, the University of Chicago Renaissance Society partnered with The Philadelphia Museum of Art to debut the first American museum presentation of Pettibon’s work. Over 500 drawings made in the 1980s and 90s were shown with a selection of ink and watercolor artist books. “That’s one reason I do a lot of baseball and surfing drawings—they have a very fluid nature. You can cut through the fluidity and movement without resorting to cartoony or gimmicky lines. It’s all pretty much there already,” Pettibon told BOMB Magazine in 1999 in an interview about his favorite subjects, installing exhibitions, and his early-now cult status-involvement with Punk music, toward which he has some animosity. “I don’t feel constrained by subject matter, I welcome practically anything into the drawing. I think it’s work that is best when there isn’t any final resolution, when you don’t arrive,” Pettibon reflected during a 2003 video profile with Art21 about his process, with insight from his parents and landlord. Pettibon, ca. 1980 Photography: Gary Leanard/Getty Seminal works, many originally included in Pettibon’s zines from the late 1970s and 80s, were showcased in Regen Projects 2008 show. Throughout 2016, David Zwirner presented a collaboration between Pettibon and Marcel Dzama in both the New York and London galleries.