Advances in Social Sciences Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COMPLETION REPORT (September 2003 – September 2010)

COMPLETION REPORT (September 2003 – September 2010) THE FISHERIES IMPROVED FOR SUSTAINABLE HARVEST (FISH) PROJECT 9 December 2010 This report was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). It was prepared by Tetra Tech EM Inc. under AID Contract No. 492-C-00-03-00022-00 through the Fisheries Improved for Sustainable Harvest (FISH) Project of the Philippines’ Department of Agriculture-Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (DA-BFAR). COMPLETION REPORT 9 December 2010 The Fisheries Improved for Sustainable Harvest (FISH) Project 2003-2010 Implemented by: Department of Agriculture-Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources In partnership with: Department of the Interior and Local Government Local government units Non-governmental organizations and other assisting organizations Supported by: United States Agency for International Development AID Contract No. 492-C-00-03-00022-00 Managed by: TETRA TECH EM INC. 18/F OMM-CITRA Building, San Miguel Ave., Ortigas Center, Pasig City, Philippines Tel. (63 2) 634 1617; Fax (63 2) 634 1622 FISH Document No. 53-FISH/2010 This report was produced through support provided by the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under the terms and conditions of USAID Contract No. AID-492-C-00-03-00022-00. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the USAID. Table of Contents List of Tables &Figures ............................................................................................................... -

Stream Name Category Name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---TNT-SAT ---|EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU|

stream_name category_name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- TNT-SAT ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD 1 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 FHD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC 1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE FR |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- Information ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 MONDE FBS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT France 24 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO HD -

Fall 2020 NEW for BEJUBA! Final Delivery End December the Curious World of Linda

Fall 2020 NEW FOR BEJUBA! Final Delivery end December The Curious World of Linda Are you ready for an amazing adventure into YOUR imagination? Linda lives in a typical little town on the water’s edge. There are typical shops, typical people, with typical day to day happenings. But, Linda isn’t typical at all. Linda lives in a Curiosity Shop which is a playground like no other – fueling her imagination to go on amazing adventures! Linda doesn’t take on these adventures alone. Her best friend Louie, a stuffed saggy old Boxer dog will always be there with her. Linda LOVES Louie, especially when she’s in her imagination because this is when he comes to life! In her imagination, Linda can be anything! Watch a subtitled Episode • Ages 3-6 • 2D • 26 x 7 minutes - delivery December 2020 • A TakToon Enterprises Production for KBS, SK Broadband, and SBA. NEW FOR BEJUBA! NEW! AVAILABLE NOW Streetcat Bob Streetcat Bob is a delightful dialogue-free series. Meet Bob - a stray ginger cat living in Bowen Park alongside his animal friends. This animated adventure for preschoolers is dialogue free and based on the bestselling books and film. Based on the best selling books, 2 feature films have been produced about Streetcat Bob and his owner. The 2nd movie Live-Action Movie debuts this winter. Watch an Episode 20 x 2 min• • 2D • Comedy • Dialogue Free • A Shooting Script Film Production created by King Rollo Films for Sky UK • Written by Debbie MacDonald• and Angela Salt \ NEW FOR BEJUBA! NEW! ABC SingSong Learning the alphabet and your numbers is oh so fun. -

Broadcasting Regulatory Policy CRTC 2012-86

Broadcasting Regulatory Policy CRTC 2012-86 PDF version Ottawa, 10 February 2012 Revised list of non-Canadian programming services authorized for distribution – Annual compilation of amendments 1. In Broadcasting Public Notice 2006-55, the Commission announced that it would periodically issue public notices setting out revised lists of eligible satellite services that include references to all amendments that have been made since the previous public notice setting out the lists was issued. 2. In Broadcasting Regulatory Policy 2011-399, the Commission replaced the lists of eligible satellite services with a simplified, consolidated list known as the List of non- Canadian programming services authorized for distribution (the list). This new list came into effect 1 September 2011. 3. Accordingly, in Appendix 1 to this regulatory policy, the Commission sets out all amendments made to the list since the issuance of Broadcasting Regulatory Policy 2011-43. In addition, the non-Canadian programming services authorized for distribution that were approved up to and including 23 January 2012 are set out in Appendix 2. 4. The Commission notes that, as set out in Broadcasting Regulatory Policy 2011-226, CBS College Sports Network was renamed CBS Sports Network. This name change is reflected in Appendix 2. Secretary General Related documents • List of non-Canadian programming services authorized for distribution, Broadcasting Regulatory Policy CRTC 2011-399, 30 June 2011 • Renaming of CBS College Sports Network as CBS Sports Network on the lists of -

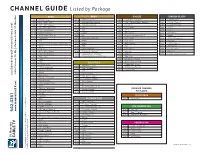

CHANNEL GUIDE Listed by Package

Listed by Package CHANNEL GUIDE BASIC BASIC BRONZE SPANISH SILVER* 104 WGN-Chicago 267 Lifetime Television 142 Fox Business Network 400 Fox Deportes 106 PBS - WPBT-Miami 269 Lifetime Movie Network 152 JNN - Jamaica News Network 402 CNN en Espanol 108 NBC - WTVJ-Miami 273 TV Guide Network 155 EuroNews 404 E! Latin America 110 CW - WPIX-New York 274 TNT 156 CCTV News 406 GLITZ 112 FOX - WSVN-Miami 276 TBS 182 JCTV 410 HTV 114 Bulletin Channel 278 Space 186 Vh1 Classic 411 MuchMusic 115 TV15 - SXM Cable TV 280 BET 190 Reggae Entertainment TV 412 Infinito 116 CaribVision 297 Game Show Network 195 BET Gospel 414 Caracol Television 119 RFO 309 EWTN 208 Fight Now! 416 Pasiones 120 Special Events Channel - SXM Cable TV 311 3ABN 217 Golf Channel 419 EWTN Espanol 121 3SCS 314 TBN 219 TVG 421 TBN Enlace 122 BVN TV 337 DWTV (German) 238 Fashion TV 424 Disney Junior 126 ABC - WPLG-Miami 418 Azteca International 245 Halogen 428 Baby TV 127 CBS - WFOR-Miami 900 - Galaxie Music Channels* 246 Baby TV 430 La Familia Cosmovision (refer to channel category for listing) 130 TeleCuraco 949 256 Teen Nick 136 CNBC 290 Sundance Channel 138 CNN SOLID GOLD 316 The Church Channel 146 Headline News 324 France 24 (French) 123 WWOR-New York 148 CNN International 325 TV5 Monde (French) 150 One Caribbean TV 151 Weather Channel 332 EuroChannel 177 A&E 153 MSNBC 184 MTV Hits USA 157 BBC World 192 CMT Pure Country 160 France 24 (English) 204 Fox Soccer Channel 162 Animal Planet 282 Africa Channel 166 Lifetime Real Women 284 G4 .net 168 TruTV X 286 Sony Entertainment TV 175 National Geographic PREMIUM CHANNEL 292 Warner Channel 179 Discovery Channel PACKAGES 313 Smile of a Child 191 Tempo SPORTSMAX 194 CENTRIC 196 MTV PLATINUM PLUS 200 SportsMax 206 Big Ten Network 131 CBC - Canada innovativeS 209 ESPN Caribbean 140 Fox News Channel w. -

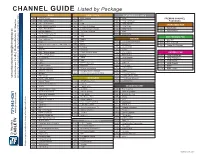

CHANNEL GUIDE Listed by Package

Listed by Package CHANNEL GUIDE BASIC BASIC cont’d PLATINUM PLUS cont’d 104 WGN-Chicago 262 BBC America 288 Spike PREMIUM CHANNEL 106 PBS - WPBT-Miami 264 E! 500 HBO Caribbean PACKAGES 108 NBC - WTVJ-Miami AXN 266 502 HBO Signature SPORTSMAX PAK 110 CW - WPIX-New York 267 Lifetime Television 506 HBO PLUS SportsMax 112 FOX - WSVN-Miami 269 Lifetime Movie Network 512 HBO Family 200 SportsMax2 114 Bulletin Channel 273 TV Guide Network 524 MAX 202 115 TV15 - SXM Cable TV 274 TNT 528 MAX Prime 116 CaribVision 276 TBS ZEE PREMIUM PAK One Caribbean TV BRONZE 117 278 Space 340 Zee TV RFO 142 Fox Business Network 119 280 BET 342 Zee Cinema Special Events Channel - SXM Cable TV 155 EuroNews 120 290 Bravo 346 Alpha Etc Punjabi 121 3SCS 294 UPlifting 156 CCTV News 122 BVN TV 296 Cinemax 182 JCTV 126 ABC - WPLG-Miami 297 Game Show Network 186 Vh1 Classic HBO/MAX PAK 127 CBS - WFOR-Miami 309 EWTN 195 BET Gospel 500 HBO Caribbean 130 TeleCuracao 311 3ABN 208 FOX Sports2 502 HBO Signature 136 CNBC 314 TBN 217 Golf Channel 506 HBO PLUS 138 CNN 337 DWTV (German) 246 Baby TV 512 HBO Family 146 Headline News 408 Univision 256 Teen Nick 524 MAX 148 CNN International 418 Azteca International 258 CalaClassics 528 MAX Prime 151 Weather Channel 900 - Stingray Music Channels 281 Aspire 153 MSNBC 950 (refer to channel category for listing) 316 Hillsong Channel 157 BBC World 324 France 24 (French) [email protected] Join us on Face Book and Like us: http://www.facebook.com/StMaartenCable 160 France 24 (English) SOLID GOLD 325 TV5 Monde (French) 162 -

Foreign Satellite & Satellite Systems Europe Africa & Middle East Asia

Foreign Satellite & Satellite Systems Europe Africa & Middle East Albania, Austria, Belarus, Belgium, Bosnia & Algeria, Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Herzegonia, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Congo Brazzaville, Congo Kinshasa, Egypt, France, Germany, Gibraltar, Greece, Hungary, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Macedonia, Libya, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Morocco, Moldova, Montenegro, The Netherlands, Norway, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Somalia, South Africa, Sudan, Tanzania, Tunisia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Uganda, Western Sahara, Zambia. Armenia, Ukraine, United Kingdom. Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Cyprus, Georgia, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, Yemen. Asia & Pacific North & South America Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, Canada, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, China, Hong Kong, India, Japan, Kazakhstan, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Puerto Rico, United Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Macau, Maldives, Myanmar, States of America. Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Nepal, Pakistan, Phillipines, South Korea, Chile, Columbia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Uruguay, Venezuela. Uzbekistan, Vietnam. Australia, French Polynesia, New Zealand. EUROPE Albania Austria Belarus Belgium Bosnia & Herzegovina Bulgaria Croatia Czech Republic France Germany Gibraltar Greece Hungary Iceland Ireland Italy -

Philippines in View Philippines Tv Industry-In-View

PHILIPPINES IN VIEW PHILIPPINES TV INDUSTRY-IN-VIEW Table of Contents PREFACE ................................................................................................................................................................ 5 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................... 6 1.1. MARKET OVERVIEW .......................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2. PAY-TV MARKET ESTIMATES ............................................................................................................................... 6 1.3. PAY-TV OPERATORS .......................................................................................................................................... 6 1.4. PAY-TV AVERAGE REVENUE PER USER (ARPU) ...................................................................................................... 7 1.5. PAY-TV CONTENT AND PROGRAMMING ................................................................................................................ 7 1.6. ADOPTION OF DTT, OTT AND VIDEO-ON-DEMAND PLATFORMS ............................................................................... 7 1.7. PIRACY AND UNAUTHORIZED DISTRIBUTION ........................................................................................................... 8 1.8. REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT .............................................................................................................................. -

American Broadcasting Company from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Jump To: Navigation, Search for the Australian TV Network, See Australian Broadcasting Corporation

Scholarship applications are invited for Wiki Conference India being held from 18- <="" 20 November, 2011 in Mumbai. Apply here. Last date for application is August 15, > 2011. American Broadcasting Company From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search For the Australian TV network, see Australian Broadcasting Corporation. For the Philippine TV network, see Associated Broadcasting Company. For the former British ITV contractor, see Associated British Corporation. American Broadcasting Company (ABC) Radio Network Type Television Network "America's Branding Broadcasting Company" Country United States Availability National Slogan Start Here Owner Independent (divested from NBC, 1943–1953) United Paramount Theatres (1953– 1965) Independent (1965–1985) Capital Cities Communications (1985–1996) The Walt Disney Company (1997– present) Edward Noble Robert Iger Anne Sweeney Key people David Westin Paul Lee George Bodenheimer October 12, 1943 (Radio) Launch date April 19, 1948 (Television) Former NBC Blue names Network Picture 480i (16:9 SDTV) format 720p (HDTV) Official abc.go.com Website The American Broadcasting Company (ABC) is an American commercial broadcasting television network. Created in 1943 from the former NBC Blue radio network, ABC is owned by The Walt Disney Company and is part of Disney-ABC Television Group. Its first broadcast on television was in 1948. As one of the Big Three television networks, its programming has contributed to American popular culture. Corporate headquarters is in the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City,[1] while programming offices are in Burbank, California adjacent to the Walt Disney Studios and the corporate headquarters of The Walt Disney Company. The formal name of the operation is American Broadcasting Companies, Inc., and that name appears on copyright notices for its in-house network productions and on all official documents of the company, including paychecks and contracts. -

Channel Lineup

† 49 ABC Family 122 Nicktoons TV 189 VH1 Soul 375 MAX Latino Southern † † 50 Comedy Central 123 Nick Jr. 190 FX Movie Channel 376 5 StarMAX † † Westchester 51 E! 124 Teen Nick 191 Hallmark Channel 377 OuterMAX † † February 2014 52 VH1 125 Boomerang 192 SundanceTV 378 Cinemax West † † 53 MTV 126 Disney Junior 193 Hallmark Movie Channel 379 TMC On Demand 2 WCBS (2) New York (CBS) † † 54 BET 127 Sprout 195 MTV Tr3s 380 TMC Xtra 3 WPXN (31) New York (ION) 55 MTV2 131 Kids Thirteen 196 FOX Deportes 381 TMC West 4 WNBC (4) New York (NBC) † 2† † 56 FOX Sports 1 132 WLIW World 197 mun 382 TMC Xtra West 5 WNYW (5) New York (FOX) 57 Animal Planet 133 WLIW Create 198 Galavisión 400-413 Optimum Sports & 6 WRNN (62) Kingston (IND) † † 58 truTV 134 Trinity Broadcasting Network 199 Vme Entertainment Pak 7 WABC (7) New York (ABC) 59 CNN Headline News† 135 EWTN 291 The Jewish Channel On Demand 414 Sports Overflow 8 WXTV (41) Paterson 60 SportsNet New York 136 Daystar 300 HBO On Demand 415-429 Seasonal Sports Packages (Univisión)† 61 News 12 Traffic & Weather 137 Telecare 301 HBO Signature 430 NBA TV 9 My9 New York (MNT-WWOR) 62 The Weather Channel 138 Shalom TV 302 HBO Family 432-450 Seasonal Sports Packages 10 WLNY (55) Riverhead (IND) † 64 Esquire Network 140 ESPN Classic 303 HBO Comedy 460 Sports Overflow 2 11 WPIX (11) New York (CW) † † 66 C-SPAN 2 141 ESPNEWS 304 HBO Zone 461-465 Optimum Sports & 12 News 12 Westchester † † 67 Turner Classic Movies 142 FXX 305 HBO Latino Entertainment Pak 13 WNET (13) New York (PBS) Channel Lineup Channel † 68 Religious -

Vietnam to Air Two-Hour Special

#GreatJobs C NTENT page 4 www.contentasia.tv l www.contentasiasummit.com Creevey’s Omni Channels Asia signs Oona/ Telkomsel deal Alliance delivers 30 channels in 2018/9 Gregg Creevey’s new joint venture, Omni Channels Asia (OCA), has partnered with Indonesia’s mobile-centric OTT aggrega- tor Oona to launch up to 30 new genre- focused channels in Indonesia in 2018/9. The Oona deal gives the linear/VOD channels access to Telkomsel’s 135 million mobile customers across the country. The first eight channels went up this month, two months after Multi Channels Asia announced its OCA joint venture with U.S.-based streaming channels provider TV4 Entertainment. The Indonesian channels include Inside- Outside, a global channel rolling out through TV4 Entertainment’s strategic partnership with U.K. indie all3media. Asia’s Got Talent returns to AXN Sony Networks Asia kicks off talent hunt season three Sony Pictures Television Networks Asia kicks off the third edition of big-budget talent search, Asia’s Got Talent, this week. Production is led by Derek Wong, who returned to the Singapore-based regional network earlier this year as vice president of production. Online auditions open on 16 May and run until 9 July on the AXN site. Open auditions will be held from June in major cities around the region. Locations have not yet been announced. Entries are open to performers in 15 countries. 14-27 MAY 2018 page 1. C NTENTASIA 14-27 May 2018 Page 2. Hong Kong’s CA backs Big issues top BCM talking points relaxed media regulations N.Korea, China, IP ownership top Busan agenda Hong Kong’s Communications Author- ity (CA) is backing a relaxation of TV and radio regulations proposed by the territory’s Commerce and Economic Development Bureau. -

PDF Format Or in HTML at the Following Internet Site

Broadcasting Public Notice CRTC 2008-8 Ottawa, 18 January 2008 Regulatory policy Revised lists of eligible satellite services – Annual compilation of amendments 1. In A new approach to revisions to the Commission’s lists of eligible satellite services, Broadcasting Public Notice CRTC 2006-55, 28 April 2006, the Commission announced that it would periodically issue public notices setting out revised lists that include references to all amendments that have been made since the previous public notice setting out the lists was issued. 2. In the present public notice, the Commission sets out references to all amendments made to the revised lists since Revised lists of eligible satellite services, Broadcasting Public Notice CRTC 2007-2, 12 January 2007. These references are set out in Appendix 1 to this public notice. The lists of eligible satellite services approved as of 31 December 2007 are set out in Appendix 2. Secretary General This document is available in alternative format upon request, and may also be examined in PDF format or in HTML at the following Internet site: http://www.crtc.gc.ca Appendix 1 to Broadcasting Public Notice 2008-8 Amendments made to the lists of eligible satellite services since Revised lists of eligible satellite services, Broadcasting Public Notice CRTC 2007-2, 12 January 2007 Addition of Caracol Television International, HTV and El Gourmet.com to the lists of eligible satellite services for distribution on a digital basis, Broadcasting Public Notice CRTC 2007-3, 12 January 2007; Addition of MBC Channel (America)