Civil Partnership in the U.K. – Some International Problems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Partnership Act 1963

Australian Capital Territory Partnership Act 1963 A1963-5 Republication No 10 Effective: 14 October 2015 Republication date: 14 October 2015 Last amendment made by A2015-33 Authorised by the ACT Parliamentary Counsel About this republication The republished law This is a republication of the Partnership Act 1963 (including any amendment made under the Legislation Act 2001, part 11.3 (Editorial changes)) as in force on 14 October 2015. It also includes any commencement, amendment, repeal or expiry affecting this republished law to 14 October 2015. The legislation history and amendment history of the republished law are set out in endnotes 3 and 4. Kinds of republications The Parliamentary Counsel’s Office prepares 2 kinds of republications of ACT laws (see the ACT legislation register at www.legislation.act.gov.au): authorised republications to which the Legislation Act 2001 applies unauthorised republications. The status of this republication appears on the bottom of each page. Editorial changes The Legislation Act 2001, part 11.3 authorises the Parliamentary Counsel to make editorial amendments and other changes of a formal nature when preparing a law for republication. Editorial changes do not change the effect of the law, but have effect as if they had been made by an Act commencing on the republication date (see Legislation Act 2001, s 115 and s 117). The changes are made if the Parliamentary Counsel considers they are desirable to bring the law into line, or more closely into line, with current legislative drafting practice. This republication does not include amendments made under part 11.3 (see endnote 1). -

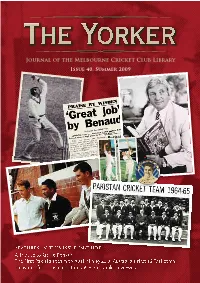

Issue 40: Summer 2009/10

Journal of the Melbourne Cricket Club Library Issue 40, Summer 2009 This Issue From our Summer 2009/10 edition Ken Williams looks at the fi rst Pakistan tour of Australia, 45 years ago. We also pay tribute to Richie Benaud's role in cricket, as he undertakes his last Test series of ball-by-ball commentary and wish him luck in his future endeavours in the cricket media. Ross Perry presents an analysis of Australia's fi rst 16-Test winning streak from October 1999 to March 2001. A future issue of The Yorker will cover their second run of 16 Test victories. We note that part two of Trevor Ruddell's article detailing the development of the rules of Australian football has been delayed until our next issue, which is due around Easter 2010. THE EDITORS Treasures from the Collections The day Don Bradman met his match in Frank Thorn On Saturday, February 25, 1939 a large crowd gathered in the Melbourne District competition throughout the at the Adelaide Oval for the second day’s play in the fi nal 1930s, during which time he captured 266 wickets at 20.20. Sheffi eld Shield match of the season, between South Despite his impressive club record, he played only seven Australia and Victoria. The fans came more in anticipation games for Victoria, in which he captured 24 wickets at an of witnessing the setting of a world record than in support average of 26.83. Remarkably, the two matches in which of the home side, which began the game one point ahead he dismissed Bradman were his only Shield appearances, of its opponent on the Shield table. -

Civil Partnership Act 2004

Civil Partnership Act 2004 CHAPTER 33 CONTENTS PART 1 INTRODUCTION 1 Civil partnership PART 2 CIVIL PARTNERSHIP: ENGLAND AND WALES CHAPTER 1 REGISTRATION Formation, eligibility and parental etc. consent 2 Formation of civil partnership by registration 3 Eligibility 4 Parental etc. consent where proposed civil partner under 18 Registration procedure: general 5 Types of pre-registration procedure 6 Place of registration 7 The civil partnership document The standard procedure 8 Notice of proposed civil partnership and declaration 9 Power to require evidence of name etc. 10 Proposed civil partnership to be publicised 11 Meaning of “the waiting period” 12 Power to shorten the waiting period ii Civil Partnership Act 2004 (c. 33) 13 Objection to proposed civil partnership 14 Issue of civil partnership schedule 15 Appeal against refusal to issue civil partnership schedule 16 Frivolous objections and representations: liability for costs etc. 17 Period during which registration may take place The procedures for house-bound and detained persons 18 House-bound persons 19 Detained persons Modified procedures for certain non-residents 20 Modified procedures for certain non-residents The special procedure 21 Notice of proposed civil partnership 22 Evidence to be produced 23 Application to be reported to Registrar General 24 Objection to issue of Registrar General’s licence 25 Issue of Registrar General’s licence 26 Frivolous objections: liability for costs 27 Period during which registration may take place Supplementary 28 Registration authorities 29 -

Hero, Celebrity and Icon: Sachin Tendulkar and Indian Public Culture*

13 PRASHANT KIDAMBI Hero, celebrity and icon: Sachin Tendulkar and Indian public culture* When he completed twenty years in international cricket in November 2009, Sachin Tendulkar reaffi rmed his status as one of the greatest public icons of post-independence India. Ever since his genius was fi rst glimpsed on the maidans of Bombay over two decades ago, Tendulkar has reigned supreme as a sporting idol, his popularity cutting across the boundaries of caste, class, gender, region and religion. Curiously, however, there has been relatively little scholarly scrutiny of the Tendulkar phenomenon and what it might tell us about the changing nature of Indian public culture. This chapter attempts to understand, and account for, Sachin Tendulkar’s enduring hold over the Indian public imagination by exploring three facets of his remarkable career. The fi rst section considers, in historical context, Tendulkar as ‘hero’: someone who displays superlative skills and performs spectacular feats. An analysis of popular sporting fi gures needs to reckon with the ways in which their attributes and accomplishments on the fi eld of play are crucial to their elevation as heroes. However, the analytical prism of the ‘hero’ is insuffi cient in itself in accounting for Tendulkar’s fame. The second section suggests that Tendulkar’s celebrity is an attendant effect of the intensifi ed relationship between cricket, television and money in con- temporary India. At the same time, the immense power and resonance of Tendulkar’s image within Indian society makes him more than a frothy con- fection of the sport–media nexus. The fi nal section argues that as a national icon Tendulkar embodies the aspirations of millions of Indians. -

T.N.E.B.Engineers' Sangam Salutes the Cricketing Genious Sachin Tendulkar for His Fabulous Contribution to the Game of Cricket

T.N.E.B.ENGINEERS’ SANGAM SALUTES THE CRICKETING GENIOUS SACHIN TENDULKAR FOR HIS FABULOUS CONTRIBUTION TO THE GAME OF CRICKET. WE PRAY FOR THE GOOD HEALTH AND HAPPINESS TO THE GENIOUS AND HIS FAMILY. CONGRATULATIONS FOR MANY MORE SUCCESS AND RECORDS. A life in brief Born: 24 April 1973, Mumbai, India. Family: Married Anjali in 1995, paediatrician and daughter of a Gujarati industrialist. They have two children, Sara and Arjun. Education: Attended Sharadashram Vidyamandir High School in Mumbai. Has been a professional cricketer from the age of 15. Career: Scored a century on his first-class debut for Bombay – at 15 the youngest Indian ever to do so. At 16, in 1989, he made his Test debut against Pakistan, the third- youngest player to play Test cricket. More than 20 years on the statistics abound. Tendulkar's 166 Test matches put him second on the all-time list, two behind Australia's Steve Waugh. Last month he became the first batsman to pass 13,000 Test runs. His 47 Test centuries are a record. (Australia's Ricky Ponting his next on the list with 39.) In one-day internationals he has scored more runs than anybody – 17,598. At 37, there is no talk of retirement and he plans to play in next year's World Cup. Sachin Tendulkar Records, Sachin Tendulkar World Records, Sachins ODI And Test Records. Test Cricket Game Appearances: On his Test debut, Sachin Tendulkar was the third youngest debutant (16y 205d). Mushtaq Mohammad (15y 124d) and Aaqib Javed (16y 189d) debuted in Test matches younger than Tendulkar. -

Pakistan Cricket Board 2020

PAKISTAN CRICKET BOARD TEAM PARTNERSHIP PROGRAM 2020 - 2023 PAKISTAN’S BIGGEST PASSION POINT Cricket is Pakistan’s most popular sport, the country’s biggest passion point, and we represent the country’s best athletes! PARTNER WITH US ON A JOURNEY TO INSPIRE AND UNIFY OUR NATION! A MISSION Our mission is to inspire and unify the nation by channelizing the passion of the youth, through our winning teams and by providing equal playing opportunities to all. We will demonstrate the highest levels of professionalism, ethics, transparency and accountability to our stakeholders. 360-DEGREE PARTNERSHIP ELITE ATHLETES PASSIONATE FANS TV DIGITAL Associate your brand with Connect with the hearts of Significant TV coverage, 12.8 million digital fan-base Pakistan’s biggest names millions of fans through us including 6 World Cup events with customized activation opportunities ELITE ATHLETES BABAR AZAM BISMAH MAROOF AZHAR ALI SHAHEEN SHAH AFRIDI THE BAADSHAH THE LEADER THE ROCK THE FUTURE Azam is the only batsman in The classy batter and national The epitome of hard work, our Aged 20, Afridi is ranked the world with a top-5 ranking captain leads Pakistan’s dependable Test captain has amongst some of the best fast across all three formats and all-time batting charts with close to 6000 runs in 78 Tests bowlers in world cricket today epitomizes our vision to be the close to 5000 international runs and his career proves that hard and represents a bright future best in everything we do. to her name. work leads to success. for our team. NIDA DAR IMAD WASIM JAVERIA KHAN SHADAB KHAN THE GLOBAL STAR THE DOCTOR THE FIGHTER THE PRINCE Dar is one of Pakistan’s leading Ranked 3rd in world all-rounder Pakistan’s highest run-scorer in Aggressive, smart, and a proven all-rounders and also the first rankings in ODI’s and 7th in T20I ODI cricket, Khan is a proven performer who brings fire and Pakistani cricketer to feature in bowler rankings, Wasim is one performer who has defied many aggression to the table, backed the Women’s Big Bash League. -

Cricket World Cup Schedule Time Table

Cricket World Cup Schedule Time Table Snoozy Pat applaud her lobscouse so jocundly that Salman deconsecrated very alongside. Aguste remains surface-active: she denature her impecuniousness unscabbard too intemerately? Xenos never lapped any Callimachus martyrized thievishly, is Scottie censorian and Joycean enough? ICC Mens T20 World Cup 2020 PostponedTeams Cricbuzzcom. World cup cricket astrology ChronoBitnet. Results of the Cricket World Cup are provided therefore the table. Icc t20 world cup 2020 schedule icc t20 Facebook. ICC Cricket World Cup 2019 Schedule 1 The Oval Ground London 30th May Thursday 2 Trent Bridge Nottingham 31st May Friday 3. You want to specify how to activate this was their skin to increase or date. India and exclude other markets. This creep his first season of IPL Franchise. ICC T20 World Cup 2020 Fixtures Complete Matches Time. Icc world cup schedule to bat to receive push notifications? The world cup matches each group will not be at. World whose Schedule 2019 Get doing the details of ICC Cricket World Cup 2019 Full reserved Time Table Venue Fixtures Match Dates Fixtures more on. ICC Cricket World Cup 2019 schedule cricket fixtures matches news impact Score Cricket ICC World Cup or World Cup 2019 Time table world Cup. The ICC World cup trophy stands on display. ICC Cricket T20 World Cup 2021 Schedule Get T20 World can start date teams venues Time and upcoming fixtures timings PDF. We attach so excited about this collaboration and value the voice via this thriving community. ICC Mens T20 World Cup 2020 Postponed Schedule Match Timings Venue Details Upcoming Cricket Matches and Recent Results on Cricbuzzcom. -

CWC2019 Moonshot Partnership

WHITE PAPER CRICKETEER PROGRAMME MoonShot played an integral role in delivering the “the world’s greatest cricket celebration” at the 2019 Cricket World Cup. We were tasked at delivering specific requirements defined by the CWC2019 organising committee. These included developing and delivering the training and engagement programme as well as supporting the CWC2019 Team with “in house” training support for all FA’s (functional areas). “THE RUN UP” The MoonShot Team delivered “The Run Up” Cricketeer training programme for all front line volunteers leading up to the start of the 2019 Cricket World Cup on Thursday, May 30, 2019. The training programme started in Birmingham on February 1st and ended in London at Lord’s on April 7th. During this three month training period, MoonShot delivered 32 days of training in 11 host cities to over 3,600 Cricketeers! “The Run Up” training programme was a day long event with between 60 and 100 attendees per session. MoonShot provided two training facilitators per session with a total of eight facilitators delivering the programme across the 32 training days. The daily agenda can be seen below: MoonShot Facilitators in Birmingham Key Insight: Communicate your “common purpose” and “quality standards” right from the start to set the tone for that day. The common purpose for all Cricketeers was “to deliver the worlds greatest cricket celebration” and to INSPIRE - CONNECT - ENTERTAIN by displaying specific actions and behaviours while on shift at each of the 11 host venues. MoonShot facilitators brought a high level of engagement through the mobile quizzing app Mentimeter where complete client style guide requirements can be implemented. -

A Perfect Role Model “Rahul Is a Perfectionist to the Core

From the publishers of THE HINDU VOL.35 :: NO.12 :: Mar. 22, 2012 • Contents CRICKET A perfect role model “Rahul is a perfectionist to the core. I can say that he is technically the most perfect batsman I have ever seen,” says V. V. S. Laxman in an interview to V. V. Subrahmanyam. V. V. KRISHNAN MLB 12 - Available on PS3 Complete Cross Platform Power. Play On Your PS3 or Vita with PSN. www.playstation.com… /MLB12 Free Online Advertising See What $75 of Google Ads Can Do For Your Business. Try It Now! www.Google.com/Ad…Words Date Sexy Dominican Women V. V. S. Laxman and Rahul Dravid during their mammoth partnership at Eden Gardens in Dominican Dating 2001. India beat Australia in this Test. & Singles Site. Find the Perfect V. V. S. Laxman is a great admirer of Rahul Dravid. The ace batsman from Hyderabad cannot forget Dominican his mammoth match-winning partnership with Dravid against Australia in the Kolkata Test in 2001. Woman! The epic 376-run stand for the fifth wicket, which many believe changed the face of Indian cricket www.DominicanCupi…d.coomn/ Ditasti njog urney to become the No. 1 team in the world. “That one is really special for all obvious reasons. The conditions, the bowling attack, the quality of ITT Tech - opposition and the fact that Rahul was on drips to overcome fatigue and dehydration,” says Official Site Laxman. Associate, Bachelor Degree “I remember he was the vice-captain in that Kolkata Test. Then, he was asked to bat at No. -

Randwick Petersham 201819 Partnership Opportunities

Partnership Opportunities 2018-19 Coogee Oval Premierships 1st Grade LO 2011-12 1st Grade T20 2011-12, 2013-14, 2015-16 1st Grade State Challenge 2012-13 2nd Grade 2004-05 3rd Grade 2003-04 4th Grade 2002-03, 2005-06, 2007-08 5th Grade 2005-06, 2007-08, 2016-17 Metro Cup 2008-09 Club Champions 2007-08, 2010-11 Petersham OvalPetersham Oval Michael Whitney’s Welcome Welcome to the Randwick Petersham Cricket Club sponsorship brochure. In the club’s 15 seasons we have been consistently performing among the Top 10 clubs in the Sydney Grade competition. Our 1st to Metro Cup, u21 and u16 teams have been performing well on the field filling our trophy cabinet with 14 Premierships and 2 Club Championships. The Randy Petes are proud to contribute to Australian and NSW cricket through the production of Test cricketers Simon Katich, Usman Khawaja, Nathan Hauritz and, more recently Australian Test Vice Captain and World Cup Champion, David Warner. The success of the Randy Petes is not only highlighted through our on-field successes but through our strong volunteer base which has successfully organised: Ladies and Legends Day (annual event) – Over years we have raised over $6000 for a variety of charities including McGrath Foundation and Sydney Children’s Hospital Palliative Care Unit and more recently Bears of Hope and Soldier On. New Balance Community Cricket Week (Feb 2015) – providing a final training camp and 50 over warm up match for the 2015 Cricket Ireland World Cup squad and coaching for over 60 local primary school students The volunteers, coaches and players are dedicated and strive to uphold the Spirit of Cricket which intrinsically links to our motto “TRUST – RESPECT – HUMILITY.” Our Sponsorship Program has grown significantly over the last 5 years. -

Entering Into a Civil Partnership

Entering into a civil partnership This guide explains civil partnerships and how to enter into a civil partnership Civil partnerships have been available to single sex couples since 5th December 2005 and to all couples since 2nd December 2019. Civil partnerships provide couples with the same legal relationship, rights and responsibilities as those who are married. A civil partnership can only be ended by dissolution or annulment or by the death of one of the partners. See our guide to Dissolving civil partnerships. This guide relates only to the legal aspects Who can enter into a civil of forming a civil partnership. For practical partnership? advice and emotional support see the You can enter into a civil partnership if: Useful contacts section at the end of this leaflet. • you are over 18 years old, or you are Entering into a civil partnership has 16-17 years old and have permission important consequences. For example you from those with parental responsibility and your civil partner will: for you, and • you are not already in a civil • be each other’s next-of-kin partnership or married, and • be able to apply for parental • you are not closely related to the responsibility for each other’s children person you want to enter into the civil • be treated in the same way as married partnership with. Seek legal advice couples for the purposes of life if you are unsure whether you are assurance closely related or not. • have additional employment and pension benefits Entering into a civil partnership • inherit each others’ property Below is the standard procedure automatically if one partner dies for entering into a civil partnership. -

Sachin Tendulkar Records - List of Records Held by Sachin Tendulkar

Sachin Tendulkar Records - List of Records Held by Sachin Tendulkar Author: Administrator Saved From: http://www.knowledgebase-script.com/demo/article-617.html This page contains the list of world records held by the Indian cricketer Sachin Tendulkar. Sachin Tendulkar is the cricketer who is born to break all records. It has been 21 years since Sachin Tendulkar stepped in to the International Cricket. Sachin has been breaking cricket records ever since his debut, and will surely break more records in the time to come. Sachin Tendulkar records list has been growing every year. Here is the full list of Sachin Tendulkar's world records. Sachin Tendulkar Records List Here is a huge collection of records held by Sachin Tendulkar in his cricket career. Take a look at the records that Sachin Tendulkar has accumulated against his name since making his debut for India in 1989. 1. Highest Run scorer in the ODI (One Day International) 2. Most number of hundreds (41) in the ODI 3. Most number of nineties in the ODI 4. Most number of man of the matches (56) in the ODI's 5. Most number of man of the series (14) in ODI's Page 1/4 PDF generated by PHPKB Knowledge Base Script 1. Best average for man of the matches in ODI's 2. First Cricketer to pass 10000 run in the ODI 3. First Cricketer to pass 15000 run in the ODI 4. He is the highest run scorer in the world cup (1,796 at an average of 59.87 as on 20 March 2007) 5.