Survey of College Students by the National Association

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix A: Name Index

1997 Directory of Pollution Prevention in Higher Education APPENDIX A: NAME INDEX Appendix A: Name Index • 141 NAME INSTITUTION DEPARTMENT # A Ahlert, Robert C. RAMS Environmental Inc. 183 Allen, David University of Texas at Austin Chemical Engineering 184 Allison, Richard University of Houston—Clear Lake Business and Public Administration 48 Anderson, Paul Illinois Institute of Technology Chemical and Environ Engineering 227 Andrews, Clinton J. Princeton University Public and International Affairs 367 Andrews, Richard U of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Environ Sciences & Engineering 366 Annis, Phillip (Jack) UW—Milwaukee Co–op Extension Solid and Haz Waste Education Center 169 Arnold, Matthew Mgmt Institute for Environ and Bus 61 Ashford, Nicholas Mass Institute of Technology Ctr for Tech, Policy & Indust Devt 368 Atchison, Michael University of Virginia School of Commerce 45 Atkinson, John University of Missouri—Columbia Engineering Extension 145 Atreya, Arvind University of Michigan Industrial Assessment Center 114 Austrian, Ziona Cleveland State College Great Lakes Environ Finance Ctr 62 Ausubel, Jesse Rockefeller University Program for the Human Environ 278 B Babatunde, Ade Minnesota Office of Env Assistance 170 Baillod, C. Robert Michigan Technological University Civil and Environmental Engineering 228 Baker, Craig M. Consumnes River College Environmental Technology Program 131 Baker, Kenneth R. Dartmouth College Business Administration 27 Ball, Terence University of Minnesota Social Sciences 313 Barker, John R. University of Michigan Atmospheric, Oceanic, & Space Sciences 386 Barnett, Stanley M. University of Rhode Island Chemical Engineering 115 Bawn, Kathleen University of California—Los Angeles Political Science 369 Becker, Monica M. University of Massachusetts—Lowell Mass Toxics Use Reduction Institute 116 Beckman, Eric J. -

Association of Social Work Boards Introduction This Handbook Was Designed to Help You Register for and Take the ASWB Social Work Licensing Examinations

® ASWB Examination Candidate Handbook Contents Introduction 1 About ASWB 1 Preparing to take the ASWB Examination 3 Make sure you are eligible 3 Register for the exam 4 Authorization to Test 6 Schedule your exam 7 Take the exam 9 Examination security 11 ASWB Security Tip Line 12 Monitoring of results 12 After the exam 12 Content outlines 15 Sample Questions 19 School codes 21 Index 26 Copyright © 2013 by the Association of Social Work Boards Introduction This handbook was designed to help you register for and take the ASWB social work licensing examinations. This is not a complicated process, but it is important that you follow the registration steps carefully. Missing a step, or making a mistake during registration, can delay your examination, or prevent you from taking it entirely. Take the time to read through this handbook before you start to register—it will make the examination process easier for you and for the people who will be helping you along the way. If you have any additional questions, you can call the Association of Social Work Boards at 1-888-579-3926. You may also find it useful to visit our website, www.aswb.org. Finally, congratulations on your efforts to become a licensed social worker. In the midst of the paperwork involved in applying for and receiving your jurisdiction’s license, it’s easy to forget that what you’re doing is very important—not only to you, but to the people you will be serving. About ASWB You will be taking one of the examinations developed by the Association of Social Work Boards (ASWB). -

Employee Directory for Barton Community College

Employee Directory for Barton Community College Please note: to view the employee directory in more detail, please click on one of the links below to navigate to that section in this document. Voters Board of Trustees President of Barton Community College Assistant to the President Vice President of Administration Bookstore Business Office Facility Management Human Resources Printing Services Director of Athletics Coaches Sports Information Sports Medicine Director of Grants Chief Information Officer Information Services—Information Technology Director of Institutional Research Institutional Research Executive Director of Institutional Advancement Public Relations & Marketing Shafer Gallery Vice President of Instruction Academics Center for Innovation & Excellence Learning Resources Liberal Arts and Sciences Mathematics, English and Essential Skills Military Academics, Technical Education and Outreach Programs Healthcare & Public Service Education Workforce Training and Community Education Workforce Training & Economic Development Vice President of Student Services Admissions Child Development Center Educational Opportunity Center (EOC) Enrollment Services Financial Aid Retired Senior Volunteer Program (RSVP) Student Life Student Support Services (SSS) Testing, Advisement & Career Services Title IX Coordinator Upward Bound (BCUB) Upward Bound (CKUB) BOARD OF TRUSTEES | https://bartonccc.edu/community/boardoftrustees PRESIDENT | All phone numbers have a 620 area code unless otherwise indicated. * On-campus extensions are the last 3 digits of the phone number. Carl Heilman President A-Bldg., Rm. 120, 792-9301 [email protected] Ph.D. Iowa State University President Emeritus (Deceased) Jimmie L. Downing, Ph.D. PRESIDENT | Assistant to the President Amye Schneider Assistant to the President A-Bldg., Rm. 122, 792-9302 [email protected] A.A.S. Barton County Community College Lora Zink Administrative Assistant A-Bldg., Rm. -

2019-2020 Graduate Academic Catalog

Saint Leo University Graduate Academic Catalog 2019-2020 ii Catalog Home Announcements contained in this publication are subject to change without notice and may not be regarded in the nature of binding obligations to the University. The University reserves the right to change any provisions or requirements. When students matriculate with Saint Leo University, they come under the academic requirements of the edition of the University catalog at that time. Students may graduate under these academic requirements within a period of five years even though subsequent catalogs may change. Academic requirements include curriculum matters. Grading practices, tuition, fees, and other matters are subject to change at the discretion of the University and are not considered to be "academic requirements." Should new changes be to their advantage, students may graduate under the conditions of the newer catalog. However, because academic programs are subject to requirements imposed by outside accrediting or certifying agencies, such outside requirements shall supersede prior conditions. Saint Leo University is committed to policies that ensure that there is no discrimination on the basis of age, gender, race, color, creed, religion, national origin, or disability. Saint Leo University complies with the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974 (as amended). Saint Leo University has a strong commitment to principles of equal employment opportunity and equal access to education. Saint Leo University does not discriminate on the basis of age, color, disability, ethnic origin, genetic information, sex, gender, nationality, race, religion, or veteran status, or any other category protected by federal, state, or local law in its educational programs, admissions policies, financial aid, employment, or other school administered programs. -

FICE Code List for Colleges and Universities (X0011)

FICE Code List For Colleges And Universities ALABAMA ALASKA 001002 ALABAMA A & M 001061 ALASKA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY 001005 ALABAMA STATE UNIVERSITY 066659 PRINCE WILLIAM SOUND C.C. 001008 ATHENS STATE UNIVERSITY 011462 U OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE 008310 AUBURN U-MONTGOMERY 001063 U OF ALASKA FAIRBANKS 001009 AUBURN UNIVERSITY MAIN 001065 UNIV OF ALASKA SOUTHEAST 005733 BEVILL STATE C.C. 001012 BIRMINGHAM SOUTHERN COLL ARIZONA 001030 BISHOP STATE COMM COLLEGE 001081 ARIZONA STATE UNIV MAIN 001013 CALHOUN COMMUNITY COLLEGE 066935 ARIZONA STATE UNIV WEST 001007 CENTRAL ALABAMA COMM COLL 001071 ARIZONA WESTERN COLLEGE 002602 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 001072 COCHISE COLLEGE 012182 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 031004 COCONINO COUNTY COMM COLL 012308 COMM COLLEGE OF THE A.F. 008322 DEVRY UNIVERSITY 001015 ENTERPRISE STATE JR COLL 008246 DINE COLLEGE 001003 FAULKNER UNIVERSITY 008303 GATEWAY COMMUNITY COLLEGE 005699 G.WALLACE ST CC-SELMA 001076 GLENDALE COMMUNITY COLL 001017 GADSDEN STATE COMM COLL 001074 GRAND CANYON UNIVERSITY 001019 HUNTINGDON COLLEGE 001077 MESA COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001020 JACKSONVILLE STATE UNIV 011864 MOHAVE COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001021 JEFFERSON DAVIS COMM COLL 001082 NORTHERN ARIZONA UNIV 001022 JEFFERSON STATE COMM COLL 011862 NORTHLAND PIONEER COLLEGE 001023 JUDSON COLLEGE 026236 PARADISE VALLEY COMM COLL 001059 LAWSON STATE COMM COLLEGE 001078 PHOENIX COLLEGE 001026 MARION MILITARY INSTITUTE 007266 PIMA COUNTY COMMUNITY COL 001028 MILES COLLEGE 020653 PRESCOTT COLLEGE 001031 NORTHEAST ALABAMA COMM CO 021775 RIO SALADO COMMUNITY COLL 005697 NORTHWEST -

Graduate Catalog 2019-2020

0 CLARKSON UNIVERSITY GRADUATE CATALOG 2019-2020 Clarkson University is a nationally ranked research university and the institution of choice for more than 4,000 enterprising, high-ability scholars from diverse backgrounds who embrace challenge and thrive in a rigorous, highly collaborative learning environment. We add value to our students’ education by partnering with leading businesses, industries, and thought leaders to bring relevance to the challenges and needs of a modern world in which the boundaries of knowledge, discipline, nations, and cultures blur. We encourage students to question the status quo, push the limits of what is known, and to apply their ingenuity to develop fresh solutions to real-world challenges. For more than 100 years, our graduates have achieved extraordinary professional success, risen to societal challenges, and advanced the global economy ethically and responsibly. Among our 38,000 alumni, one in five is a CEO, senior executive or owner of a company. Founded in 1896 to honor Thomas S. Clarkson, the University's main campus is located in the “college town” of Potsdam, NY on a historic 640-acre wooded homestead in the foothills of the Adirondack Park. With three other universities nearby, Clarkson community members enjoy a constantly changing social and intellectual quality of life largely influenced by our proximity to the north slope of the Adirondacks; easy drives to Lake Placid as well as Ottawa and Montreal, Canada; and a high level of regional camaraderie to encourage innovative partnerships in small business development, arts, tourism, recreation, agriculture and green energy. The University also includes The Capital Region Campus for graduate education in Schenectady, New York, and The Beacon Institute for Rivers and Estuaries for environmental research and education in Beacon, New York. -

The Faculty, of Which He Was Then President

Carleton Moves CoddentJy Into Its Second Century BY MERRILL E. JARCHOW 1992 CARLETON COLLEGE NORTHFIELD, MINNESOTA Q COPYRIGHT 1992 BY CARLETON COLLEGE, NORTHFIELD, MINNESOTA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Libray of Congress Curalog Card Number: 92-72408 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Cover: Old and New: Scoville (1895). Johnson Hall (admissions) / Campus Club (under construction) Contents Foreword ...................................................................................vii Acknowledgements ...................................................................xi 1: The Nason Years ........................................................................1 2: The Swearer Years ....................................................................27 3: The Edwards Years ...................................................................69 4: The Porter Year .......................................................................105 5: The Lewis Years ......................................................................121 Epilogue ..................................................................................155 Appendix .................................................................................157 iii Illustrations President John W . Nason and his wife Elizabeth at the time of Carleton's centennial ..................................................2 Isabella Watson Dormitory ...............................................................4 Student Peace March in 1970 ..........................................................15 -

Idaho State Board of Education

Disclosures - Kansas State University - Acalog ACMS™ Campus Map Contact Us About K-State Academics Admissions Research 2012-2013 Undergraduate Catalog Courses Disclosures A P H S Whole Word/Phrase State Authorization Disclaimers Advanced Search In accordance with the U.S. Department of Education’s new regulation (34 Catalog Home C.F.R. § 600.9) regarding legal authorization to provide postsecondary education through distance or correspondence education in a state in Courses which it is not physically located or in which it is otherwise subject to State jurisdiction as determined by the State, Kansas State University makes the following disclaimers per authorization by each state regulatory agency. Programs Students seeking to enroll in a Kansas State University distance education Schools/Colleges and Departments program residing outside the state of Kansas, but within the United States, District of Columbia, and U.S. Territories (excludes International locations), About the Catalog should check the University’s authorization status below or contact the Division of Continuing Education at [email protected] or (785) About the University 532-5575 or toll free at 1-800-622-2578 regarding enrollment. We will continue to serve out-of-state students while working with individual state Academic Advising authorization agencies to meet institutional authorization requirements; unless otherwise indicated. Links to each state’s regulatory agency(ies) is All-University Regulations also included. Please note that your state of residence may have unique disclosure Auxiliary Services and Facilities requirements related to authorization to offer distance education courses and programs within your state, including, but not limited to, tuition and Calendar fee waivers or adjustments. -

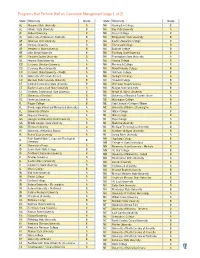

Programs That Perform Well on Classroom Management (Page 1 of 2)

Programs that Perform Well on Classroom Management (page 1 of 2) State University Grade State University Grade AL Alabama State University A MA Assumption College B AL Athens State University B MA Bay Path University A AL Auburn University B MA Boston College B AL University of Alabama in Huntsville B MA Bridgewater State University B AR Arkansas Tech University B MA Eastern Nazarene College B AR Harding University B MA Emmanuel College B AR Henderson State University B MA Endicott College B AR John Brown University B MA Fitchburg State University B AR Ouachita Baptist University B MA Framingham State University A AZ Arizona State University A MA Gordon College B CO Colorado Christian University A MA Merrimack College B CO Colorado Mesa University B MA Mount Holyoke College B CO Colorado State University – Pueblo A MA Simmons College B CO University of Colorado Denver A MA Springfield College A CO Western State Colorado University B MA Stonehill College B CT Central Connecticut State University B MA Worcester State University B CT Eastern Connecticut State University A MD Morgan State University B CT Southern Connecticut State University B MD Mount St. Mary’s University B CT University of Hartford B MD University of Maryland Eastern Shore A DC American University B MD Washington College B FL Flagler College B ME Saint Joseph’s College of Maine B FL Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University A ME University of Maine at Farmington A FL University of Miami A MI Albion College B GA Augusta University A MI Alma College B GA Georgia Southwestern State University A MI Hope College A GA Middle Georgia State University B MI Madonna University B GA Thomas University A MI Michigan Technological University B HI University of Hawaii at Manoa A MI Northern Michigan University B IA Buena Vista University A MI Spring Arbor University A Faith Baptist Bible College and Theological MN Augsburg College B IA B Seminary MN College of Saint Scholastica B IA University of Iowa A MN Minnesota State University – Mankato B ID Lewis-Clark State College B MN St. -

PAUL HANSTEDT Washington and Lee University * 204 W. Washington St

PAUL HANSTEDT Washington and Lee University * 204 W. Washington St. * Lexington, VA 24450 * [email protected] _________________________________________________________________________ EDUCATION Ph.D. Literature, The Ohio State University M.A. Creative Writing, Iowa State University B.A. Literature, Luther College (Phi Beta Kappa, magna cum laude) PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Washington and Lee University (2019-present) Director of the Center for Houston H. Harte Center for Teaching and Learning Design and Implement • Powerful model for both student support and faculty pedagogical development, with an emphasis on peer-to-peer teaching and support, with the end goal of developing a campus ecosystem of thoughtful, deliberate teaching and learning • Key program features include Faculty Teaching Fellows program; formative observation collaborations for faculty; faculty consultations; improved peer tutor training and administration • Ongoing curricular components in coordination with relevant departments, including but not limited to ePortfolios, course and faculty evaluation, and peer observation programs Coordinate • With multiple and varied entities across campus on both the student and academic affairs sides, including but not limited the First- and Second-year Deans, Student Health Services, Career Services, Assessment, Deans and Associate Deans of the Arts and Sciences, The Williams School, and the Law School, Academic Technologies, Library Services, and Development Offices • Ongoing pedagogical development including regular workshops and -

ASAIHL Conference and Board Meeting 15 December 2020

ASAIHL Conference and Board meeting 15 December 2020 This is the first time in our 65 years of ASAIHL history that we conducted an online election of officers. Tan Sri Professor Dato Dr. Syed Jalaludin, former ASAIHL President, who has served as Chairman of the Election Committee for the past 20 years presented the nomination list for endorsement by the General Conference and the following were duly nominated and duly seconded at the election on 15 December 2020 at 15.50 hours Bangkok time. 1. Prof. Dr. Yoshihisa Baba, President, Soka University, Japan, President of ASAIHL 2. Prof. Dr. Mohammad Nasih, Rector of Universitas Airlangga, Vice-President of ASAIHL 3. Datin Dr. Anita B Z Abdul Aziz, Vice Chancellor, University Brunei Darussalam 4. Prof. Dr. Bundhit Eua-arporn, President, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand 5. Prof. Dr. Alojzy Z. Nowak, President, University of Warsaw, Poland 6. Prof. Way Kuo, President, City University of Hong Kong 7. Prof. Dr. Chandrika N Wijeyaratne, Vice-Chancellor, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka 8. Prof. Dr. Etienne Saur, Rector, University of Science & Technology of Hanoi 9. Prof. Dr. Mohammad Mehdi Tehranchi, President, Islamic Azad University, Iran 10. Prof. Dr. Chung-Ming Kuan, President, National Taiwan University 11. Dr. Michel Eddi, President Director General of CIRAD, France 12. Prof. Amy Storey, President, Keuka College, New York, U.S.A. 13. Assoc. Prof. Seiha Diep, Rector, Build Bright University 14. Fr. Marcelo V. Manimtim, President of Adamson University 15. Prof. Dato’ Dr. Mohammad Shatar bin Sabran, Vice-Chancellor, Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris Acceptance speech by newly elected President of ASAIHL Address by Soka University President at the ASAIHL Board Meeting (12/15) Most respected Dr. -

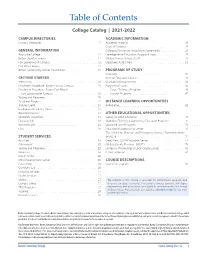

Barton Community College Catalog 2021-2022 Part 1

Table of Contents College Catalog | 2021-2022 CAMPUS DIRECTORIES ACADEMIC INFORMATION Campus Directories . .2 . Academic. Integrity . .29 . Code of Conduct . 29 GENERAL INFORMATION College to University Articulation Agreements . 29 About the College . 11 Developmental Education Purpose & Goals . 29 Barton County Campus . .12 . .Military . Service. School Credit . 30 Fort Leavenworth Campus . 13. Outcomes. Assessment . 30. Fort Riley Campus . .14 . Barton Community College Foundation . 15. .PROGRAMS . OF STUDY Overview . 31 GETTING STARTED General Education Courses. 32. Admissions . 16. .Graduation . Requirements. 32. Enrollment Procedure: Barton County Campus. 18. .Programs of Study . 36 Enrollment Procedure: Barton Fort Riley & Career Technical Programs . .39 . Fort Leavenworth Campus . .19 . Transfer. Programs . 47 Testing and Placement . .19 . Academic Progress . .20 . .DISTANCE . LEARNING OPPORTUNITIES Transfer Credit . .20 . BARTonline. .. 65 Graduation Residency Hours. 21. Repeated Courses . .21 . .OTHER . .EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES Residency Statement . 21. Center. for . Adult Education . 70. Financial Aid . 22 Workforce Training & community Education Programs . 70 Residence Life . 23 Upward Bound Programs. .70 . Cost . 24. Educational. Opportunity. Center . 70. The Hazardous Materials and Emergency Services Training Institute STUDENT SERVICES (HMESTI) . 71. Activities . 25. Great. Plains. OSHA. Education Center . .72 . Advisement . .25 . .Military . .On-site . Training - (MOST). 79. Testing and Placement . 25. .University . Partnerships