THE MUSEUM PROPOSITION the How to Make a Smart Museum Programming Series Was Made Possible by the Efroymson Family Fund

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newberry Seminars Chicago Culture

SUMMER 2015 Newberry Seminars Chicago Culture Best Addresses: Notable Residential Streets in Chicago Tuesdays, 6:15 – 7:45 pm June 9 – August 4 (class will not meet July 7; we will meet from 6:15 – 8:15 pm on June 16) Through a series of walking tours, we will explore some of Chicago’s best addresses—streets known for significant domestic architecture, influential residents, or notable historical events. Examples will be drawn from a variety of neighborhoods, including Prairie Avenue, the Gold Coast, Streeterville, Lake Shore East, Lakeview, and Hyde Park. We will pay special attention to how residential architecture and urban design shape local identities as well as the way historic landmarks promote tourism, commerce, and design innovation. Only the Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, 1929. From first session will meet at the Newberry. Eight The Stanolind Record, a Standard Oil publication. sessions, $200. Newberry Midwest MS Barrett-Sandburg: Box 3, Folder 38 Diane Dillon holds a PhD in art history from Yale University and has been a regular seminar instructor post-meeting field trips to contemporary Chicago at the Newberry since 2003. establishments that illustrate the evening’s conversation. Six sessions, $180. Chicago Playwrights and Their Plays Bill Savage is associate professor of instruction at Tuesdays, 6 – 7:30 pm Northwestern University and has taught Newberry June 9 – July 28 Seminars since 1992. He has also worked in area bars This seminar offers the unique opportunity to since 1980. meet Chicago-based playwrights, engage in an in-depth dialogue about their work, and gain an intimate glimpse into their creative process. -

DPLA Usage Statistics for January 31

Digital Public Library of America Analytics Digital Public Library of A… Go to report Illinois DPLA Stats Jan 31, 2020 - Feb 29, 2020 All Users 100.00% Sessions Total Illinois Items Viewed on DPLA Item Pages 1,019 % of Total: 0.30% (341,244) Total Illinois Items Viewed in Exhibitions 0 % of Total: 0.00% (341,244) Total Illinois Items Viewed in Primary Source Sets 0 % of Total: 0.00% (341,244) Total Illinois Click Throughs 890 % of Total: 0.26% (341,244) Total Illinois Events 1,909 % of Total: 0.56% (341,244) Total Illinois Items Viewed in DPLA (In Item Pages, Exhibitions, and Primary Source Sets) Total Events 150 100 50 … Feb 2 Feb 4 Feb 6 Feb 8 Feb 10 Feb 12 Feb 14 Feb 16 Feb 18 Feb 20 Feb 22 Feb 24 Feb 26 Feb 28 Total Illinois Click Throughs Total Events 100 50 … Feb 2 Feb 4 Feb 6 Feb 8 Feb 10 Feb 12 Feb 14 Feb 16 Feb 18 Feb 20 Feb 22 Feb 24 Feb 26 Feb 28 Top 10 Events by Contributing Institution Event Action Total Events Unique Events University of Illinois at Chicago 250 237 Newberry Library 193 177 University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library 193 175 Illinois State University 160 157 Chicago History Museum 88 86 Pullman State Historic Site 88 79 Southern Illinois University Carbondale 83 82 Chicago Public Library 66 61 Illinois State Historical Society 55 49 Northern Illinois University 47 46 Top 10 Illinois Events by Item Event Label Total Events Unique Events 712586ef98b840352ffa930ba99fd467 : Ku Klux Klan 15 12 061aac7d02d8f660088fdf1e97a1a22e : Fisherman, Cotton Spinners, Cheeseman, Bran Seller, Milk Seller, Maltese Lady 11 10 509f5485f2cc5346304b4b8932a65dcc : Jane Addams Hull House Association, Hull House 10 10 804f30ee5163869fa826e374ab6ac933 : Abbott Laboratories, The Abbot Alkaloidal Co. -

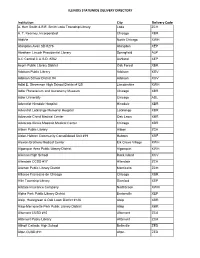

Illinois Statewide Delivery Directory

ILLINOIS STATEWIDE DELIVERY DIRECTORY Institution City Delivery Code A. Herr Smith & E.E. Smith Loda Township Library Loda ZCH A. T. Kearney, Incorporated Chicago XBR AbbVie North Chicago XWH Abingdon-Avon SD #276 Abingdon XEP Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Springfield ALP A-C Central C.U.S.D. #262 Ashland XEP Acorn Public Library District Oak Forest XBR Addison Public Library Addison XGV Addison School District #4 Addison XGV Adlai E. Stevenson High School District #125 Lincolnshire XWH Adler Planetarium and Astronomy Museum Chicago XBR Adler University Chicago ADL Adventist Hinsdale Hospital Hinsdale XBR Adventist LaGrange Memorial Hospital LaGrange XBR Advocate Christ Medical Center Oak Lawn XBR Advocate Illinois Masonic Medical Center Chicago XBR Albion Public Library Albion ZCA Alden-Hebron Community Consolidated Unit #19 Hebron XRF Alexian Brothers Medical Center Elk Grove Village XWH Algonquin Area Public Library District Algonquin XWH Alleman High School Rock Island XCV Allendale CCSD #17 Allendale ZCA Allerton Public Library District Monticello ZCH Alliance Francaise de Chicago Chicago XBR Allin Township Library Stanford XEP Allstate Insurance Company Northbrook XWH Alpha Park Public Library District Bartonville XEP Alsip, Hazelgreen & Oak Lawn District #126 Alsip XBR Alsip-Merrionette Park Public Library District Alsip XBR Altamont CUSD #10 Altamont ZCA Altamont Public Library Altamont ZCA Althoff Catholic High School Belleville ZED Alton CUSD #11 Alton ZED ILLINOIS STATEWIDE DELIVERY DIRECTORY AlWood CUSD #225 Woodhull -

The Newberry Annual Report 2019–20

The Newberry A nnua l Repor t 2019–20 30 Fall/Winter 2020 Letter from the Chair and the President Dear Friends and Supporters of the Newberry, The Newberry’s 133rd year began with sweeping changes in library leadership when Daniel Greene was appointed President and Librarian in August 2019. The year concluded in the midst of a global pandemic which mandated the closure of our building. As the Newberry staff adjusted to the abrupt change of working from home in mid-March, we quickly found innovative ways to continue engaging with our many audiences while making Chair of the Board of Trustees President and Librarian plans to safely reopen the building. The Newberry David C. Hilliard Daniel Greene responded both to the pandemic and to the civil unrest in Chicago and nationwide with creativity, energy, and dedication to advancing the library’s mission in a changed world. Our work at the Newberry relies on gathering people together to think deeply about the humanities. Our community—including readers, scholars, students, exhibition visitors, program attendees, volunteers, and donors—brings the library’s collection to life through research and collaboration. After in-person gatherings became impossible, we joined together in new ways, connecting with our community online. Our popular Adult Education Seminars, for example, offered a full array of classes over Zoom this summer, and our public programs also went online. In both cases, attendance skyrocketed, and we were able to significantly expand our geographic reach. With the Reading Rooms closed, library staff responded to more than 450 research questions over email while working from home. -

Artefacts XXIII, Adler Planetarium, October 14-16, 2018 Preliminary Program (Draft)

Artefacts XXIII, Adler Planetarium, October 14-16, 2018 Preliminary program (draft) Sunday, 14 10:00 - 2:00 Registration & badge pick-up Free museum exploration and sky shows at discretion w/ conference badge* *Complimentary tickets to sky shows and to the Atwood Sphere to be requested at the box office 2:00-2:15 Welcoming remarks Johnson Family Star Theater 2:15-4:00 Paper session 1, Johnson Family Star Theater: Thinking relevance through object histories Lippisch DM 1, Museum Artifact Reassessed Russel Lee, Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum The Hofgaard machine: Prototype of an ingenious invention, or just a piece of metal scrap? Dag Andteassen, Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology How science works: the 'failure' of MiniGRAIL Dirk van Delft, Rijksmuseum Boerhaave / Leiden University Collections as a spur to scholarship: Women's Great War uniforms Barton Hacker, Smithsonian Institution (emeritus) Margaret Vining, Smithsonian Institution (emeritus) 4:00-4:30: Coffee break 4:30-6:00 Paper session 2, Johnson Family Star Theater: Bringing collections to life Game On: Using Digital Technologies to Bring Collections to Life Erin Gregory, Ingenium Canada (Canada Aviation and Space Museum) “Hear My Voice”: Learning from Alexander Graham Bell’s Volta Laboratory Sound Recordings Carlene Stephens, National Museum of American History Making silent artifacts speak: Tinfoil recordings, digitization projects, and the relevance of collections Frode Weium, The Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology 6:00-7:00 - Gallery tours 7:00 - 9:00 - Conference dinner Monday, 15 8:00-9:00 - Breakfast 9:00-10:15 Roundtable, Johnson Family Star Theater: Art and Artifact: Collections, Museum Practice, and the Aesthetics of Science and Technology Claudia Swan, Northwestern University Jennifer Nelson, School of the Art Institute of Chicago Jonathan Tavares, Art Institute of Chicago Pedro M. -

CIVIL RIGHTS and SOCIAL JUSTICE Abolitionism: Activism to Abolish

CIVIL RIGHTS and SOCIAL JUSTICE Abolitionism: activism to abolish slavery (Madison Young Johnson Scrapbook, Chicago History Museum; Zebina Eastman Papers, Chicago History Museum) African Americans at the World's Columbian Exposition/World’s Fair of 1893 (James W. Ellsworth Papers, Chicago Public Library; World’s Columbian Exposition Photographs, Loyola University Chicago) American Indian Movement in Chicago Anti-Lynching: activism to end lynching (Ida B. Wells Papers, University of Chicago; Arthur W. Mitchell Papers, Chicago History Museum) Asian-American Hunger Strike at Northwestern U Ben Reitman: physician, activist, and socialist; founder of Hobo College (Ben Reitman Visual Materials, Chicago History Museum; Dill Pickle Club Records, Newberry Library) Black Codes: denied ante-bellum African-Americans living in Illinois full citizenship rights (Chicago History Museum; Platt R. Spencer Papers, Newberry Library) Cairo Civil Rights March: activism in southern Illinois for civil rights (Beatrice Stegeman Collection on Civil Rights in Southern Illinois, Southern Illinois University; Charles A. Hayes Papers, Chicago Public Library) Carlos Montezuma: Indian rights activist and physician (Carlos Montezuma Papers, Newberry Library) Charlemae Hill Rollins: advocate for multicultural children’s literature based at the George Cleveland Branch Library with Vivian Harsh (George Cleveland Hall Branch Archives, Chicago Public Library) Chicago Commission on Race Relations / The Negro in Chicago: investigative committee commissioned after the race riots -

History of the Newberry Library

Newberry Library – History of the Newberry Library Edward E. Ayer Library Room, 1943. NL Archives 15/01/03 Bx. 3, Fl.#82. The Newberry Library was founded in 1887 by a bequest of Chicago land developer and city leader Walter Loomis Newberry (1804-1868). Newberry was an early Chicago resident, arriving in the city in 1833 from Detroit. He quickly became involved in a variety of business ventures, and made his fortune in railroads, real estate, and banking. The young city also counted on Newberry’s involvement in other ways: he helped found Chicago’s Young Men’s Library Association in 1841, served on the city boards of health and education, and was president of the Chicago Historical Society from 1860 until his death. Newberry’s final decade was marked by declining health, and he traveled to France numerous times for medical treatments. He was on one of these regular journeys to France when he died at sea on Nov. 6, 1868. Newberry is buried in Chicago in Graceland Cemetery. Newberry’s will provided for the establishment of a free public library on the north side of Chicago— but only if his surviving daughters died without issue. (At the time of Newberry’s death, Chicago did not have a public library. The Chicago Public Library was founded six years after Newberry died, in 1874.) The daughters, Mary Louisa Newberry and Julia Rose Newberry, both died within 10 years of their father. Newberry’s wife, Julia Clapp Newberry, died in 1885. Newberry’s wishes for a library were finally honored two years later, when half of his estate ($2.1 million) went towards the founding of the Newberry Library. -

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Illinois Digital

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative and selected portions of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the Division of Preservation and Access application guidelines at http://www.neh.gov/grants/preservation/national-digital-newspaper-program for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Preservation and Access staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative and selected portions, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: Illinois Digital Newspaper Project Institution: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Project Director: Mary Stuart Grant Program: National Digital Newspaper Program 1100 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W., Rm. 411, Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8570 F 202.606.8639 E [email protected] www.neh.gov Illinois Digital Newspaper Project Narrative INTRODUCTION The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) Library on behalf of the Illinois Digital Newspaper Project Planning Consortium proposes to select, digitize, and make available to the Library of Congress 100,000 pages of Illinois newsprint, published between 1860 and 1922, as part of the National Digital Newspaper Program (NDNP). -

Chicago Area Disaster Response Resource File

CHICAGO AREA DISASTER RESPONSE RESOURCE FILE Compiled at the Newberry Library 2009 (Updated 2016) CONTENTS INTRODUCTION. 3 MUSEUM/ LIBRARY CONTACTS. 4 HUMAN RESOURCES. 5 SERVICES . 13 EQUIPMENT . 22 SUPPLIES . 32 INDEX . 43 ONLINE CONSERVATION & COLLECTIONS CARE RESOURCE . .44 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY. 46 2 INTRODUCTION The history of the Chicago Area Disaster Response Resource File is outlined in the original introduction written over 20 years ago and reprinted in full below. The usefulness of this resource seems more relevant than eve, however, as we enter a millennium when global warming and its effects – extreme weather - have become common. The original document, intended to assist in the planning and implementation of disaster response and recovery, remains a practical tool in the preparation of Chicago area disaster response manuals for institutions large and small. It has been updated to include new members of DRAT and also includes websites and email addresses of individuals and companies as appropriate. The document includes listings for Human Resources, Suppliers, Services, and Equipment, and is available through the Newberry Library as a pdf with active links to listings. For more information or to obtain a copy, please contact me at [email protected] Barbara Korbel Collections Conservator(Retired) The Newberry Library February 2009 The idea for this resource file evolved from two independent projects begun by two different groups of professionals. Both projects, however, were inspired by the same event. In the late afternoon of July 11, 196, an exposed water main behind the Chicago Historical Society broke and began shooting water into the air. Before it could be shut off the water had filled a large foundation pit which had been excavated as part of the CHS building project. -

Downtown Transit Sightseeing Guide

All Aboard! Buses Trains Fares* Quick Ride Guide Chicago Transit Authority This guide will show you how to use Chicago Transit Riding CTA Buses Riding CTA Trains Base/Regular Fares From the Loop 151511 SHERIDIDANAN Deducted from Transit Value in a Ventra Authority (CTA) buses and trains to see Downtown Chicago, CTA buses stop at bus shelters or signs Each rail line has a color name. All trains operate Downtown Transit Account on a Ventra Card or Attraction Take Bus or Train: North Michigan Avenue, and a few places beyond. that look like this. Signs list the service TOTO DEEVO VO NN daily until at least midnight, except the Purple Line Express (see contactless bankcard Full Reduced** days/general hours, route number, name map for hours). Trains run every 7 to 10 minutes during the day Art Institute, Chicago Cultural Ctr. Short walk from most buses and all rail lines ♦ Chinatown Red Line train (toward 95th/Dan Ryan) The CTA runs buses and elevated/subway trains (the ‘L’) and destinations, and the direction of travel. and early evening, and every 10 to 15 minutes in later evening. ‘L’ train fare $2.50 $1.25 in the State Street Subway south to that serve Chicago and 35 nearby suburbs. From Here’s a quick guide to boarding in the Downtown area: Bus fare† $2.25 $1.10 When a bus approaches, look at the sign Cermak-Chinatown X or bus 62 South on State Downtown, travel to most attractions on one bus or train. 22 Clark above the windshield. It will first show the 22 Clark Blue Line Dearborn Street subway Transfer (up to two additional ‘L’ train or bus 25¢ 15¢ DuSable Museum 4 south on Michigan (starts at Randolph) Downtown route number and route name, then change rides within two hours) FirstMerit Bank Pavilion at 146 south on State or 130 (Memorial Day 24 Wentworth Brown Line Loop elevated Northerly Island Park weekend thru Labor Day) east on Jackson We Have Answers to show the destination. -

MUSEUM Oi.Uchicago.Edu

oi.uchicago.edu MUSEUM oi.uchicago.edu Overleaf: Old Assyrian clay tablet with list of legal claims of Enlil-bani. Business document of a merchant trading in a Hittite city. OIM A2531. Clay. Kaneş, Turkey. 19th–18th century bc. After Theo van den Hout, “The Rise and Fall of Cuneiform Script in Hittite Anatolia,” in Visible Language: Inventions of Writing in the Ancient Middle East and Beyond, edited by Christopher Woods, p. 99, fig. 4.1 (Oriental Institute Museum Publications 32; Chicago: The Oriental Institute, 2010) oi.uchicago.edu museum MUSEUM The Museum continues to be a hub of frenetic activity with special exhibits, improvements to the galleries, archives, and storage areas, the implementation of conservation grants, loans in and out, accommodating visiting researchers, filling photo orders, and record sales at the Suq. Details of the activities of each section of the Museum are found in the following pages. In contrast to the continuity of the Museum’s programs and activities, we regret to report a major change: the departure of Chief Curator Geoff Emberling, in mid-October 2010. The Museum prospered and matured under Geoff’s leadership. He completed the reinstallation of the permanent galleries and then instituted the special exhibits program, overseeing nine exhibits over his six-year tenure at the museum. Under his guidance, the special exhibits matured as procedures for their review and implementation were established. The exhibits became more complex and professional, with exhaustive and attractive catalogs and, more recently, with audio guides and interactive components. Working in partnership with Director Gil Stein, Geoff led the Museum forward on the adoption of an integrated database that will change the way the entire Oriental Institute will work, conduct research, and interact with scholars and the public. -

Syllabus Rev 100708Ja&Dd&Wg

Mapping and Art in the Americas NEH Summer Institute The Newberry Library, July 12 – August 13, 2010 James Akerman and Diane Dillon, Co-directors Syllabus (revised, July 2010) Except where noted, all sessions are in the Towner Fellows’ Lounge, on the east end of the second floor. U nless otherwise indicated , all afternoons Tuesday through Friday are free for research and reading. The reading rooms are open Tuesday – Friday, 9 AM – 5 PM, Saturday, 9 AM – 1 PM. Please note that books cannot be paged 12 – 1 PM. The building is closed on Sundays. Part 1: Maps in Art, Art in Maps Monday, July 12, 2010 8:30 – 9:00 AM Refreshments 9:00 AM – 12:00 PM Morning Session 1 (including tour of Library): The Problem of Art and Cartography: Perspectives from Cartographic and Art History James Akerman and Diane Dillon Readings: Cosgrove 2005; Karrow 2007; Robinson 1966, pp. 3-24; Woodward 1987, pp. 1-9 1:30 – 4:30 PM Afternoon session (Special Collections Reading Room): Workshop and introduction to collections 5:45 PM Evening: Welcome dinner at Café Iberico, 739 N. LaSalle Dr. Tuesday, July 13 9:00 AM – 12:00 PM Morning Session 2: Mapping in Art, part I Nina Katchadourian (independent artist, New York), Laurie Palmer (Associate Professor of Sculpture, Art Institute of Chicago), Dianna Frid (Assistant Professor, Studio Arts, University of Illinois-Chicago), Gregory Knight (independent curator, Chicago and Berlin) Readings: Harmon and Clemans 2009 (all) 1:30 – 2:30 PM Library services orientation JoEllen Dickie and Lisa Schoblasky 2:30 – 6:30 PM Individual conferences (Smith Center) Wednesday, July 14 9:00 – 10:00 AM Group breakfast (Towner Fellows Lounge) 10:00 AM – 1:00 PM Morning Session 3: Crossing Boundaries: Between Maps and Art Edward S.