A Study of the Isle of Man, 1558-1660

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thomas, Lord Stanley by Michael Iliffe

Thomas, Lord Stanley by Michael Iliffe Thomas Lord Stanley was the son of Thomas, 1st Baron Stanley. The 1st baron was a younger son of Cheshire gentry who had been elevated to the peerage. Thomas, his son, became the 2nd Baron Stanley at his father’s death in 1459, and in 1461 became Chief Justice of Cheshire. In 1472 he married Eleanor, the sister of Richard Neville (“the kingmaker”). They had four sons that we know of; George, Edward, Edmund and James. George was to become Lord Strange, James joined the Church, Edward and Edmund played no part in the politics of the time. Lord Stanley’s brother, William, later became Sir William Stanley. After the death of his wife, Eleanor, he married Margaret Beaufort in 1482, and became the step-father of Henry Tudor, son of Edmund Tudor, the Duke of Richmond, who died in 1458. Margaret was the daughter of John, 1st Duke of Somerset; she brought him great wealth, and a wife of breeding and accomplishment. Thomas and Margaret had no children together. During the personal rule of Henry VI, Lord Stanley became Controller of the Royal Household, and in times of crisis the court looked to him to provide troops in the North-West. Stanley’s greatest danger came in 1459, when Queen Margaret made a bid to recruit him directly in Cheshire, when the Yorkists were mobilising and sought assistance from the Stanleys. To add to his dilemma, his father died that year, leaving the 24 year old Thomas to weather the storm. At the Battle of Blore Heath that year, young Stanley played a game of brinkmanship and held his retinue and levies some miles from the encounter. -

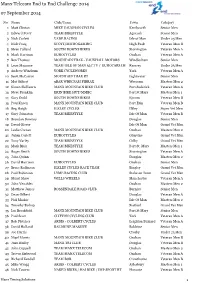

Manx Telecom End to End Challenge 2014 07 September 2014

Manx Telecom End to End Challenge 2014 07 September 2014 No Name Club/Team Town Category 1 Matt Clinton MIKE VAUGHAN CYCLES Kenilworth Senior Men 2 Edward Perry TEAM BIKESTYLE Agneash Senior Men 3 Nick Corlett VADE RACING Isle of Man Under 23 Men 4 Nick Craig SCOTT/MICROGAMING High Peak Veteran Men B 5 Steve Calland SOUTH DOWNS BIKES Storrington Veteran Men A 6 Mark Harrison EUROCYCLES Onchan Veteran Men A 7 Ben Thomas MOUNTAIN TRAX - VAUXHALL MOTORS Windlesham Senior Men 8 Leon Mazzone TEAMCYCLING ISLE TEAM OF MAN 3LC.TV / EUROCARS.IM Ramsey Under 23 Men 9 Andrew Windrum YORK CYCLEWORKS York Veteran Men A 10 Scott McCarron MOUNTAIN TRAX RT Lightwater Senior Men 11 Mat Gilbert 9BAR WRECSAM FIBRAX Wrecsam Masters Men 2 12 Simon Skillicorn MANX MOUNTAIN BIKE CLUB Port Soderick Veteran Men A 13 Steve Franklin ERIN BIKE HUT/MMBC Port St Mary Masters Men 1 14 Gary Dodd SOUTH DOWNS BIKES Epsom Veteran Men B 15 Paul Kneen MANX MOUNTAIN BIKE CLUB Port Erin Veteran Men B 16 Reg Haigh ILKLEY CYCLES Ilkley Super Vet Men 17 Gary Johnston TEAM BIKESTYLE Isle Of Man Veteran Men B 18 Brendan Downey Douglas Senior Men 19 David Glover Isle Of Man Grand Vet Men 20 Leslie Corran MANX MOUNTAIN BIKE CLUB Onchan Masters Men 2 21 Julian Corlett EUROCYCLES Glenvine Grand Vet Men 22 Tony Varley TEAM BIKESTYLE Colby Grand Vet Men 23 Mark Blair TEAM BIKESTYLE Port St. Mary Masters Men 1 24 Roger Smith SOUTH DOWNS BIKES Storrington Veteran Men A 25 John Quinn Douglas Masters Men 2 26 David Harrison EUROCYCLES Onchan Senior Men 27 Bruce Rollinson ILKLEY CYCLES RACE -

TIES of the TUDORS the Influence of Margaret Beaufort and Her Web of Relations on the Formation and Preservation of Tudor Rulership

TIES OF THE TUDORS The Influence of Margaret Beaufort and her Web of Relations on the Formation and Preservation of Tudor Rulership P.V. Smolders Student Number: 1607022 Research Master Thesis, August 2016 Supervisor: Dr. Liesbeth Geevers Leiden University, Institute for History Ties of the Tudors The Influence of Margaret Beaufort and her Web of Relations on the Formation and Preservation of Tudor Rulership. Pauline Vera Smolders Student number 1607022 Breestraat 7 / 2311 CG Leiden Tel: 06 50846696 E-mail: [email protected] Research Master Thesis: Europe, 1000-1800 August 2016 Supervisor: Dr. E.M. Geevers Second reader: Prof. Dr. R. Stein Leiden University, Institute for History Cover: Signature of Margaret Beaufort, taken from her first will, 1472. St John’s Archive D56.195, Cambridge University. 1 Table of Contents List of Abbreviations 3 Introduction 4 1 Kinship Networks 11 1.1 The Beaufort Family 14 1.2 Marital Families 18 1.3 The Impact of Widowhood 26 1.4 Conclusion 30 2 Patronage Networks 32 2.1 Margaret’s Household 35 2.2 The Court 39 2.3 The Cambridge Network 45 2.4 Margaret’s Wills 51 2.5 Conclusion 58 3 The Formation and Preservation of Tudor Rulership 61 3.1 Margaret’s Reputation and the Role of Women 62 3.2 Mother and Son 68 3.3 Preserving Tudor Rulership 73 3.4 Conclusion 76 Conclusion 78 Bibliography 82 Appendixes 88 2 Abbreviations BL British Library CUL Cambridge University Library PRO Public Record Office RP Rotuli Parliamentorum SJC St John’s College Archives 3 Introduction A wife, mother of a king, landowner, and heiress, Margaret of Beaufort was nothing if not a versatile women that has interested historians for centuries. -

GD No 2017/0037

GD No: 2017/0037 isle of Man. Government Reiltys ElIan Vannin The Council of Ministers Annual Report Isle of Man Government Preservation of War Memorials Committee .Duty 2017 The Isle of Man Government Preservation of War Piemorials Committee Foreword by the Hon Howard Quayle MHK, Chief Minister To: The Hon Stephen Rodan MLC, President of Tynwald and the Honourable Council and Keys in Tynwald assembled. In November 2007 Tynwald resolved that the Council of Ministers consider the establishment of a suitable body for the preservation of War Memorials in the Isle of Man. Subsequently in October 2008, following a report by a Working Group established by Council of Ministers to consider the matter, Tynwald gave approval to the formation of the Isle of Man Government Preservation of War Memorials Committee. I am pleased to lay the Annual Report before Tynwald from the Chair of the Committee. I would like to formally thank the members of the Committee for their interest and dedication shown in the preservation of Manx War Memorials and to especially acknowledge the outstanding voluntary contribution made by all the membership. Hon Howard Quayle MHK Chief Minister 2 Annual Report We of Man Government Preservation of War Memorials Committee I am very honoured to have been appointed to the role of Chairman of the Committee. This Committee plays a very important role in our community to ensure that all War Memorials on the Isle of Man are protected and preserved in good order for generations to come. The Committee continues to work closely with Manx National Heritage, the Church representatives and the Local Authorities to ensure that all memorials are recorded in the Register of Memorials. -

ATTACHMENT for ISLE of MAN 1. QI Is Subject to the Following Laws

ATTACHMENT FOR ISLE OF MAN 1. QI is subject to the following laws and regulations of Isle of Man governing the requirements of QI to obtain documentation confirming the identity of QI=s account holders. (i) Drug Trafficking Offences Act 1987. (ii) Prevention of Terrorism Act 1990. (iii) Criminal Justice Act 1990. (iv) Criminal Justice Act 1991. (v) Drug Trafficking Act 1996. (vi) Criminal Justice (Money Laundering Offences) Act 1998. (vii) Anti-Money Laundering Code 1998. (viii) Anti-Money Laundering Guidance Notes. 2. QI represents that the laws identified above are enforced by the following enforcement bodies and QI shall provide the IRS with an English translation of any reports or other documentation issued by these enforcement bodies that are relevant to QI=s functions as a qualified intermediary. (i) Financial Supervision Commission. (ii) Financial Crime Unit of Isle of Man Constabulary. (iii) Attorney General for the Isle of Man. 3. QI represents that the following penalties apply to failure to obtain, maintain, and evaluate documentation obtained under the laws and regulations identified in item 1 above. Imprisonment for a term of up to fourteen years, or a fine or both, and imposition of conditions on a license or the revocation of a license granted by the Isle of Man Financial Supervision Commission. 4. QI shall use the following specific documentary evidence (and also any specific documentation added by an amendment to this item 4 as agreed to by the IRS) to comply with section 5 of this Agreement, provided that the following specific documentary evidence satisfies the requirements of the laws and regulations identified in item 1 above. -

The Sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories in the Brexit Era

Island Studies Journal, 15(1), 2020, 151-168 The sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories in the Brexit era Maria Mut Bosque School of Law, Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, Spain MINECO DER 2017-86138, Ministry of Economic Affairs & Digital Transformation, Spain Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London, UK [email protected] (corresponding author) Abstract: This paper focuses on an analysis of the sovereignty of two territorial entities that have unique relations with the United Kingdom: the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories (BOTs). Each of these entities includes very different territories, with different legal statuses and varying forms of self-administration and constitutional linkages with the UK. However, they also share similarities and challenges that enable an analysis of these territories as a complete set. The incomplete sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and BOTs has entailed that all these territories (except Gibraltar) have not been allowed to participate in the 2016 Brexit referendum or in the withdrawal negotiations with the EU. Moreover, it is reasonable to assume that Brexit is not an exceptional situation. In the future there will be more and more relevant international issues for these territories which will remain outside of their direct control, but will have a direct impact on them. Thus, if no adjustments are made to their statuses, these territories will have to keep trusting that the UK will be able to represent their interests at the same level as its own interests. Keywords: Brexit, British Overseas Territories (BOTs), constitutional status, Crown Dependencies, sovereignty https://doi.org/10.24043/isj.114 • Received June 2019, accepted March 2020 © 2020—Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada. -

Quintin Gill A3 Manifesto 1

HOUSE OF KEYS GENERAL ELECTION from investment and support. Development work trying (but not always managing!) to be good Thursday 29th September 2011 is progressing at the former Marine Lab. which humoured, and above all, being honest. will rejuvenate this highly visible part of Port Erin Sheading of Rushen and I welcome this private venture. However, the faltering Regeneration Schemes for Port Erin and CONCLUSION AND LOOKING AHEAD Port St Mary must be utilised more effectively to We face pressing economic challenges which will enhance the commercial viability of both Ports. require particular skills and experience from our QUINTIN GILL X Investment is not just about money. I have politicians. Teamwork and shared endeavour will committed a great deal of time and effort into need to be the guiding principles of the next supporting our communities. Since I initiated a Government; openness and candour will need to Since 2001 I have been honoured to be formal visit programme, hundreds of children characterise their relationship with the wider public. elected to serve the people of Rushen from our primary schools have learnt about the I do believe that a well led Government can get the as one of your Independent MHKs. As I House of Keys and Tynwald Court. At a secondary backing of the responsible members of Tynwald and promised ten years ago, I have applied level, Castle Rushen High School students the respect of the Manx public to make the right myself wholeheartedly to all the varied annually take part in Junior Tynwald. I know from decisions which are going to be required of us. -

School Catchment Areas Order 2O7o

Statutory Document No. 100210 EDUCATION ACT 2OO7 SCHOOL CATCHMENT AREAS ORDER 2O7O Comíng into operøtion L lønuøry 201.0 The Department of Education and Children makes this Order under section 15(a) of the Education Act 2001r. 1 Title This Order is the Sdrool Catchment Areas Order 20L0 and shall come into operation on the l,stlaruary 2011, 2 Commencement This order comes into operation on the l't January 2011 3 Interpretation In this Order "the order maps" means lhreL2maps arurexed to this Order and entitled "Mup No.1 referred to in the School Catchrrrent Areas Order 2010" to "Map No.12 refer¡ed to in the Sclrool Catchment Areas Order 2010 4 Catchment areas of primary schools (1) Úr relation to eadr primary sdrool specified in colrrmn 1 of Sdredule L, the area shown edged with a thick yellow line on one or more of the order maps and indicated by the corresponding nurnber specified in colrrmn 2 of that Sdredule is designated as the catchment area of that sdrool. (2) The parishes constituted for purposes of the Roman Catholic Churdr and annexed to St Anthony's, StJoseph's and StMary's churdres are designated as the catdrment area of St Mary's Roman Catholic School, Douglas. (3) There are no designated catctLment areas for St Thomas' Churdr of England Primary School, Douglas and the Bunscoill Ghaelgagh, StJohn's. t 2oo1 c.33 Price: f,2.00 1 5 Catchment areas of secondary schools (1) Subject to paragraphs (2) and (3), in relation to eadr secondary school specified in column 1 of Sdredule 2, the areas designated by article 2 as the catdrment areas of the corresponding primary sdrools specified in column 2 of that Schedule are together designated as the catchment area of that school. -

Buchan School Magazine 1971 Index

THE BUCHAN SCHOOL MAGAZINE 1971 No. 18 (Series begun 195S) CANNELl'S CAFE 40 Duke Street - Douglas Our comprehensive Menu offers Good Food and Service at reasonable prices Large selection of Quality confectionery including Fresh Cream Cakes, Superb Sponges, Meringues & Chocolate Eclairs Outside Catering is another Cannell's Service THE BUCHAN SCHOOL MAGAZINE 1971 INDEX Page Visitor, Patrons and Governors 3 Staff 5 School Officers 7 Editorial 7 Old Students News 9 Principal's Report 11 Honours List, 1970-71 19 Term Events 34 Salvete 36 Swimming, 1970-71 37 Hockey, 1971-72 39 Tennis, 1971 39 Sailing Club 40 Water Ski Club 41 Royal Manx Agricultural Show, 1971 42 I.O.M, Beekeepers' Competitions, 1971 42 Manx Music Festival, 1971 42 "Danger Point" 43 My Holiday In Europe 44 The Keellls of Patrick Parish ... 45 Making a Fi!m 50 My Home in South East Arabia 51 Keellls In my Parish 52 General Knowledge Paper, 1970 59 General Knowledge Paper, 1971 64 School List 74 Tfcitor THE LORD BISHOP OF SODOR & MAN, RIGHT REVEREND ERIC GORDON, M.A. MRS. AYLWIN COTTON, C.B.E., M.B., B.S., F.S.A. LADY COWLEY LADY DUNDAS MRS. B. MAGRATH LADY QUALTROUGH LADY SUGDEN Rev. F. M. CUBBON, Hon. C.F., D.C. J. S. KERMODE, ESQ., J.P. AIR MARSHAL SIR PATERSON FRASER. K.B.E., C.B., A.F.C., B.A., F.R.Ae.s. (Chairman) A. H. SIMCOCKS, ESQ., M.H.K. (Vice-Chairman) MRS. T. E. BROWNSDON MRS. A. J. DAVIDSON MRS. G. W. REES-JONES MISS R. -

Report of Proceedings of Tynwald Court (Debates

Published by the Office of the Clerk of Tynwald, Legislative Buildings, Bucks Road, Douglas, Isle of Man. Printed by The Copy Shop Ltd., 48 Bucks Road, Douglas, Isle of Man. REPORT OF PROCEEDINGS OF TYNWALD COURT (DEBATES AND OTHER MATTERS) __________________ Douglas, Wednesday, 22nd January 2003 at 10.30 a.m. __________________ Present: The President of Tynwald (the Hon. N Q Cringle). In the Council: The Lord Bishop (the Rt Revd Noël Debroy Jones), the Attorney-General (Mr W J H Corlett QC), Hon. C M Christian, Mr D F K Delaney, Mr D J Gelling CBE, Mr J R Kniveton, Mr E G Lowey, Dr E J Mann and Mr G H Waft, with Mrs M Cullen, Clerk of the Council. In the Keys: The Speaker (the Hon. J A Brown) (Castletown); Mr D M Anderson (Glenfaba); Hon. A R Bell and Mr L I Singer (Ramsey); Mr R E Quine OBE (Ayre); Mr J D Q Cannan (Michael); Mrs H Hannan (Peel); Hon. S C Rodan (Garff); Mr P Karran, Hon. R K Corkill and Mr A J Earnshaw (Onchan); Mr G M Quayle (Middle); Mr J R Houghton and Mr R W Henderson (Douglas North); Hon. D C Cretney and Mr A C Duggan (Douglas South); Hon. R P Braidwood and Mrs B J Cannell (Douglas East); Hon. A F Downie and Hon. J P Shimmin (Douglas West); Capt. A C Douglas (Malew and Santon); Hon. J Rimington, Mr Q B Gill and Hon. P M Crowe (Rushen); with Mr M Cornwell-Kelly, Clerk of Tynwald. __________________ The Lord Bishop took the prayers. -

Ancient, British and World Coins War Medals and Decorations Historical Medals Banknotes

Ancient, British and World Coins War Medals and Decorations Historical Medals Banknotes To be sold by auction at: The Westbury Hotel Bond Street London W1S 2YF Days of Sale: Wednesday 13th November 2002 10.00 am, 11.30 am, 2.30 pm Thursday 14th November 2002 10.00 am Public viewing: 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Monday 11th November 2002 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Tuesday 12th November 2002 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Or by previous appointment Catalogue price £10 Enquiries: James Morton, Tom Eden, Paul Wood or Stephen Lloyd Cover illustrations: Lots 767-786 (front); Lot 522 (back) Front cover photography by Ken Adlard in association with 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Tel.: +44 (0)20 7493 5344 Fax: +44 (0)20 7495 6325 E-mail: [email protected] www.mortonandeden.com Important Information for Buyers All lots are offered subject to Morton & Eden Ltd.’s Conditions of Business and to reserves. Estimates are published as a guide only and are subject to review. The actual hammer price of a lot may well be higher or lower than the range of figures given and there are no fixed “starting prices”. A Buyer’s Premium of 15% is applicable to all lots in this sale. Excepting lots sold under “temporary import” rules which are marked with the symbol ‡ (see below), the Buyer’s Premium is subject to VAT at the standard rate (currently 17½%). Lots are offered for sale under the auctioneer’s margin scheme and VAT on the Buyer’s Premium is payable by all buyers. -

Cronk Keeill Abban (Old Tynwald Site)

Access Guide to Cronk Keeill Abban (Old Tynwald Site) Manx National Heritage has the guardianship of many ancient monuments in the landscape. A number of these sites are publicly accessible. Please note in most circumstances the land is not in the ownership of Manx National Heritage and visits are made at your own risk. We recognise that visiting the Island’s ancient monuments in the countryside can present difficulties for people with disabilities. We have prepared an access guide for visiting Cronk Keeill Abban (Old Tynwald Site) to help you plan your visit. This access guide does not contain personal opinions as to suitability for those with access needs, but aims to accurately describe the environment at the site. Introduction Cronk Keeill Abban in Braddan is the site of an Early Christian Keeill and was a former Viking assembly site. It is one of four historically recorded assembly sites in the Isle of Man – the others being Tynwald Hill, Castle Rushen and another in Kirk Michael. The earliest written reference to this being a Tynwald site dates from 1429. At this Tynwald sitting the record states that ‘trial by combat’ was abolished. The word Tynwald comes from the Norse thingvollr, meaning place of the parliament or assembly field. The annual meeting held at Tynwald Hill in St John’s would have been the “all-Island” meeting – smaller local groups would have met elsewhere throughout the year. The exact location of the assembly site is not clear, and the present circular dry stone enclosure was constructed in 1929 to commemorate its existence.