Bordeaux Style Red Wines in South Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wine List Lauda 2019

WINE LIST 2019 INDEX OF CONTENTS WHITE CHAMPAGNES 03 ROSE CHAMPAGNES 04 WHITE SPARKLING WINES 05 ROSE & SPARKLING WINES 06 WHITE WINES 07 GREECE 07 ITALY 13 FRANCE 16 SPAIN, AUSTRIA & GERMANY 19 HUNGURY, GEORGIAN REPUBLIC, LEBANON, AMERICA 20 AUSTRALIA 21 NEW ZEALAND 22 ROSE WINES 23 GREECE 23 ITALY, FRANCE, SPAIN, LEBANON, ARGENTINA, NEW ZEALAND 24 RED WINES 25 GREECE 25 ITALY 30 FRANCE 33 SPAIN, PORTUGAL 38 AUSTRIA, LEBANON, SOUTH AFRICA, AMERICA 39 AUSTRALIA, NEW ZEALAND 41 DESSERT WINES 42 GREECE 42 REST OF THE WORLD 43 FORTIFIED WINES 44 EAU DE VIE 44 BRANDY 44 LIQUEUR 44 CHAMPAGNES WHITE CHAMPAGNES WHITE CHAMPAGNES Grand Siecle Brut NV, Laurent Perrier, Tours-sur-Marne Brut Millesime 2008, Palmer & Co, Reims chardonnay pinot noir chardonnay, pinot noir, pinot meunier 640 252 Champ Cain 2005, Jacquesson, Avize Blanc de Noirs NV, Palmer & Co, Reims pinot noir, pinot meunier, chardonnay pinot noir, pinot meunier 593 263 Blanc de Blancs NV, Billecart-Salmon, Ay Grande Cuvee NV, Krug, Reims chardonnay chardonnay, pinot noir , pinot meunier 306 669 Fut de Chene Grand Cru NV, Henri Giraud, Ay La Grande Dame 2006, Veuve Cliquot, Reims pinot noir, chardonnay chardonnay, pinot noir 588 561 Code Noir NV, Henri Giraud, Ay Comtes de Champagne Blanc de Blancs 2007, Taittinger, Reims pinot noir chardonnay 448 514 R.D. Extra Brut 2002, Bollinger, Ay Cristal 2009, Louis Roederer, Reims pinot noir, chardonnay pinot noir , chardonnay 872 697 Brut Reserve NV, Charles Heidsieck, Reims Rare 2002, Piper Heidsieck, Reims chardonnay, pinot noir, pinot meunier -

The Shore Club Wine List

THE SHORE CLUB WINE LIST The Shore Club’s wine list is composed of a wide selection of bottles from around the world, with an emphasis on Canadian, Californian, French and Italian wine. The wines are chosen with consideration of The Shore Club’s classic steak and seafood menu an d with the intention of enhancing your dining experience. Enjoy exploring our approachable selections listed by c ountry and grape variety. Should you have any questions, or if you would like a recommendation, please do not hesitate to ask your server, on e o f o u r managers or m y s e l f . Please Enjoy, Craig Douglas Beverage Director WINES BY THE GLASS WHITE 6oz 9oz VINELAND ‘Elevation’ Riesling 2018, Niagara Escarpment VQA, Ontario, Canada .................................. 12 | 18 SERENISSIMA Pinot Grigio 2018, Veneto IGT, Italy. ................................................................................... 13 | 20 RABL ‘Ried Spiegel’ Grüner Veltliner 2018, Kamptal, Austria DAC ........................................................... 13 | 20 YEALANDS ‘Land Made’ Sauvignon Blanc 2019, Marlborough, NZ ........................................................... 14 | 21 PAUL ZINCK Pinot Gris 2017, Alsace AOC, France .................................................................................... 15 | 22 TWO SISTERS Unoaked Chardonnay 2016, Niagara Peninsula VQA, Ontario, Canada ............................ 15 | 22 GIACOMO FENOCCHIO Roero Arneis DOCG 2018, Piedmont ................................................................. 15 | 22 RODNEY STRONG -

Grape Acreage Report 2019 Crop

CALIFORNIA Grape Acreage Report 2019 Crop California Department of Food and Agriculture in cooperation with USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service April 24, 2020 MAP AND DEFINITIONS OF CALIFORNIA GRAPE PRICING DISTRICTS 1. Mendocino County Del 2. Lake County Norte 3. Sonoma and Marin Counes Siskiyou Modoc 4. Napa County 5. Solano County 6. Alameda, Contra Costa, Santa Clara, San Francisco, San Mateo, and Santa Cruz Counes 7. Monterey and San Benito Counes 8. San Luis Obispo, Santa Barbara, and Ventura Counes 9. Yolo County north of Interstate 80 to the juncon of Interstate 80 and U.S. 50 and north Shasta Lassen Trinity of U.S. 50; Sacramento County north of U.S. 50; Del Norte, Siskiyou, Modoc, Humboldt, Humboldt Trinity, Shasta, Lassen, Tehama, Plumas, Glenn, Bu0e, Colusa, Su0er, Yuba, and Sierra Counes. 10. Nevada, Placer, El Dorado, Amador, Calaveras, Tuolumne and Mariposa Counes 9 11. San Joaquin County north of State Highway 4; and Sacramento County south of U.S. 50 Tehama and east of Interstate 5 Plumas 12. San Joaquin County south of State Highway 4; Stanislaus and Merced Counes 13. Madera, Fresno, Alpine, Mono, Inyo Counes; and Kings and Tulare Counes north of Mendocino Butte Nevada Avenue (Avenue 192) Glenn Sierra 14. Kings and Tulare Counes south of Nevada Avenue (Avenue 192); and Kern County 1 Nevadaevada 15. Los Angeles and San Bernardino Counes Yuba Orange, Riverside, San Diego, and Imperial Counes Lake Colusa 16. Placer 17. Yolo County south of Interstate 80 from the Solano County line to the Juncon of 2 Interstate 80 and U.S. -

Schedule of Wine Prices to Retailers

Form PS-2B Schedule of Wine Prices to Retailers Age or Price to # of Term % Wholesalers btls. Discount of Brand Label Registration # Neutral Alcohol per per per for Type of Beverage & Brand Name NYSItem Sale Size Spirits % btl. case case Quantity Dessert Fruit Wine Cocchi Barolo Chinato BLR#TTB# 06241000000062/ comes in triangle gift box HZ9111 NYS 500ML NV 17 0.00 408.00 12 $2.00 ON 12 BT, $4.00 ON 36 BT HZ9110 NYS 1L NV 17 0.00 588.00 12 $1.00 ON 6 BT, $2.00 ON 12 BT Domaine Pinnacle Ice Apple Wine BLR#TTB# 09114001000283/ DDP4000 NYS 375ML NV 12 0.00 300.00 12 20.00% ON 6BT Cocchi Americano Bianco Aperitif Wine BLR#TTB# 09282001000302/ HZ9100 NYS 750ML NV 17 0.00 207.00 12 $1.50 ON 6BT, $2.50 ON 12BT, $3.00 ON 36BT Bonal Gentiane Quina Aperitif Wine BLR#TTB# 10029001000186/ HZ9550 NYS 750ML NV 17 0.00 186.00 12 $0.50 ON 6 BT, $1.50 ON 12 BT, $2.00 ON 36 BT Byrrh Grand Quinquina BLR#TTB# 10104001000186/ HZ9560 NYS 750ML NV 18 0.00 186.00 12 $0.50 ON 6 BT, $1.50 ON 12 BT, $2.00 ON 36 BT HZ9561 NYS 375ML NV 18 0.00 120.00 12 $4.00 ON 24 BT Cardamaro Aperitif Wine BLR#TTB# 10136001000005/ HZ9200 NYS 750ML NV 17 0.00 234.00 12 $1.50 ON 6 BT, $2.50 ON 12 BT, $3.00 ON 36 BT Villa Moresca Zibibbo Dessert Wine Sicilia BLR#TTB# 10148003000055/ VIS5700 NYS 500ML NV 16 0.00 78.00 6 Net Cocchi Americano Rosa Aperitif Wine BLR#TTB# 12232001000028/ HZ9105 NYS NV 17 0.00 207.00 12 $1.50 ON 6BT, $2.50 ON 12BT, $3.00 ON 36BT Cappelletti Aperitivo BLR#TTB# 13013001000097/ HZ9300 NYS 750ML NV 17 0.00 186.00 12 $0.50 ON 6 BT, $1.50 ON 12 BT, $2.00 ON 36 BT, $3.00 ON 60 BT Saba Yair's Winery Sweet Pomegranate Wine BLR#TTB# 16050001000489/ NYS VV 15 0.00 140.00 12 $20.00 ON 3CS, $60.00 ON 5CS Saba Yair's Winery Semi Sweet Pomegranate Wine BLR#TTB# 16050001000496/ NYS VV 15 0.00 140.00 12 $20.00 ON 3CS, $60.00 ON 5CS MHW 1129 Northern Blvd., Suite 312 Manhasset, New York 11030 Effective Month of January 2021 SCHEDULE OF WINE PRICES TO RETAILERS 1 Age or Price to # of Term % Wholesalers btls. -

2015 CHATEAU DE LA RIVIERE Fronsac AOC, Bordeaux

2015 CHATEAU DE LA RIVIERE FAKTA Fronsac AOC, Bordeaux Rødvin Drue(r): 2% Malbec, 6% Cabernet Sauvignon, Distriktet Bordeaux-distriktet Fronsac ligger i nærheden af byen Libourne nord for Dordognefloden, og har været kendt for sine 8% Cabernet Franc, 84% Merlot vine længe før, områder som fx Graves eller Médoc begyndte at plante vinstokke. Fronsac kan desuden prale med at Alkohol: 14.5% høre under en af de ældste vinlovgivninger i Bordeaux. Områdets komplekse jordbundsforhold med rige aflejringer Skruelåg: Nej nogle steder og ler- og kalkholdige eller småstens- og siliciumholdige lag i dybden andre steder, forklarer de store Varenummer: 01410511535 kvalitetsforskelle i området. De bedste vinmarker siges at ligge i den nordlige del, nær Canon-Fronsac (egen AOC), hvor sand og kalk dominerer. Navnet Canon kommer i øvrigt af, at de høje skrænter ved Fronsac blev brugt af flådens skibe, som lå for anker i Dordognefloden, til at afprøve deres kanoner. AOC'erne Fronsac og Canon-Fronsac tillader kun rødvinsproduktion, hovedsageligt på druen Merlot, tilsat Cabernet Franc (i området kaldt Bouchet), Malbec og Cabernet Sauvignon. Vinene er generelt kraftige og krydrede, ofte med god sprødhed og struktur, og de bedste af dem desuden med velour og finesse. De vinder som regel i harmoni og kompleksitet ved at blive modnet (5-10 år). Vinene fra Fronsac nævnes ofte som gode (og ofte billigere) alternativer til St. Emilion- eller Pomerol-vine. Producenten Château de la Rivière er uden tvivl et af de meste berømte vinslotte i Fronsac-området. Dets beliggenhed på La Rivière-sletten (ca. 60 m. over Dordognefloden), omgivet af 65 ha. -

Beverlys Wine List.Pdf

Okay, maybe that’s backwards, but you get the idea. Delicious. Don Julio Tequila is sponsoring this year’s Tequila Dinner and Pig Roast. We have 6 courses of cuisine ranging from house made tortilla chips and salsa to gazpa- chos and ceviche before hitting the main course of the whole, slow fire roasted pig. Tequila ambassadors will be on hand to answer all of your questions about the fruit of the agave (which is technically from the same family as the lily, not the cactus…)See you learned something already!! We begin the Margarita reception at 6PM and each course features a sip of the selected tequila and a small cocktail made from that tequila. Please join us on our new deck, downstairs un- der the sun and stars for this memo- rable, feasty evening. Reservations required for this cool event - 800-688-4142 Valued at nearly $2,500,000 • More than 14,000 bottles More than 2,000 labels • Wines from $25. to $10,450. Vintages dating from 1945 • 70 to 90 half-bottles available, 51 wines offered by the glass• Themed flights of wines National recognitions from consumer and trade magazines our team of nationally accredited Sommeliers to cheerfully assist you! Feuillatte Brut Rose NV - 98. dried watermelon and raspberries in refreshing, dry, flavorful style! Champagne Bassermann-Jordan 1999 - 58. for carrying the flavors of seafoods well. German “dry” Riesling Domaine de Cristia 2005 - 85. Fascinating, layered, dry with great “mouthfeel” White Chateauneuf Domaine de Prieure 2002 - 48. Pinot Noir from the source, earthy and ethereal Red Burgundy Vall Llach 2002 - 135. -

Bordeaux 2015 Arrivage 2015: Schon Heute Ein Legendärer Bordeaux-Jahrgang

Weinpassion für Bordeaux 2015 Arrivage 2015: Schon heute ein legendärer Bordeaux-Jahrgang. Berührendes Weinerlebnis zu einem unglaublichen Preis. 2015 Le Sacre St-Georges St-Emilion 18+/20 Gerstl Weinselektionen • Tel. 058 234 22 88 • www.gerstl.ch Bordeaux 2015: Grandiose Weine dank perfektem Wetter und herausragender Kellerarbeit. Liebe Bordeaux-Freundinnen und -Freunde Liebe Kundinnen und Kunden Wo soll man den Jahrgang 2015 einordnen? Qualitativ ohne Zweifel bei den ganz grossen Jahrgängen. Ist er noch besser als 2005, 2009 oder 2010? Ich würde sagen nicht besser, aber ganz anders auf ähnlich hohem Niveau. 2005 und 2010 zeigten Kraft, Konzentration, Mineralität und Eleganz. 2009 glänzte mit perfekter Reife, gezügelter Opulenz, enormer Fülle und toller Eleganz. 2015 hat von allen erwähnten Komponenten etwas, aber eher in gemässigter Form, das Überragende an 2015 sind die Feinheit, die Raffinesse, die unglaublich leckere Art der Weine. Die Witterungs-Verhältnisse waren absolut ideal. Der Süden des Médoc und die Regionen Pessac-Léognan, St. Emilion mit der ganzen Umgebung von Castillon über Fronsac bis Bourg und Blaye und auch Pomerol inkl. Lalande de Pomerol profitierten von absolut perfektem Erntewetter. Nur im Norden des Médoc gab es einige Regenfälle. Das wurde aber von den Top- Betrieben sehr gut gemeistert, auch hier sind einige überragende Weine ent- standen. «Dieses Jahr hat uns der Regen sogar die Qualität der Ernte geret- tet», meinte Véronique Sanders, Direktorin von Château Haut-Bailly, «immer genau dann, wenn Trockenstress drohte, gab es den nötigen Regen.» Besuchen Sie unbedingt unsere grosse Arrivage-Degustation mit den Winzern in Zürich (23.4.18, Volkshaus) und an weite- ren Orten in der Schweiz – siehe www.gerstl.ch/events Herzliche Grüsse und viel Genussvergnügen mit Bordeaux 2015! Pirmin Bilger Roger Maurer Max Gerstl Gratislieferung ab 24 Flaschen (75cl) oder ab Bestellwert Fr. -

2017 Wine Awards

2017 Wine Awards ©2017 by The Orange County Wine Society ocws.org 714.708.1636 Page 1 of 173 Purpose This booklet lists the winners of the 41st Annual OC Fair & Event Center Commercial Wine Competition. The judging took place under rigidly controlled conditions on June 3rd & June 4th, 2017, at the Hilton Hotel, Costa Mesa, California. 2,457 different wines were judged and 1,726 were awarded medals. Scope The competition includes only wines from California grown grapes including still wines, fortified wines, infused wines, and sparkling wines. This year 80 judges tasted 104 varieties and styles in 405 categories classified by price and residual sugar level. The wine samples for judging are submitted by wineries. Wines arrive at the OC Fair & Event Center grounds where they are transferred to an air-conditioned building for unpacking and cataloging. There are no entry fees; however, wineries submit 6 bottles of each wine into the competition. These wines are divided into A, B, C, D, E and F bottles. All entries are verified, comparing the entry form to computer listing to the actual bottle placed in a specific box. The A bottles are bagged and labeled by code, varietal, bottle, price code and sugar level. During the competition, the A and B bottles are moved to the competition site. Just prior to judging all A bottles are verified to ensure they are in the proper serving order. B bottles are used only if a defective A bottle is found by the judges. The judging is performed by professionals; each judge is either a winemaker or winery principal. -

The Libournais and Fronsadais

108 FRANCE THE LIBOURNAIS AND FRONSADAIS The right bank of the Dordogne River, known as THE GARAGISTE EFFECT the Libournais district, is red-wine country. In 1979, Jacques Thienpont, owner of Pomerol’s classy Vieux Château Certan, unintentionally created what would become the Dominated by the Merlot grape, the vineyards “vin de garagiste” craze, when he purchased a neighboring plot here produce deep-colored, silky- or velvety-rich of land and created a new wine called Le Pin. With a very low yield, 100 percent Merlot, and 100 percent new oak, the wines of classic quality in the St.-Émilion and decadently rich Le Pin directly challenged Pétrus, less than a mile Pomerol regions, in addition to wines of modest away. It was widely known that Thienpont considered Vieux Château Certan to be at least the equal of Pétrus, and he could quality, but excellent value and character, in the certainly claim it to be historically more famous, but Pétrus “satellite” appellations that surround them. regularly got much the higher price, which dented his pride. So Le Pin was born, and although he did not offer his fledgling wine at the same price as Pétrus, it soon trounced it on the auction IN THE MID-1950S, many Libournais wines were harsh, and market. In 1999, a case of 1982 Le Pin was trading at a massive even the best AOCs did not enjoy the reputation they do today. $19,000, while a case of 1982 Château Pétrus could be snapped Most growers believed that they were cultivating too much up for a “mere” $13,000. -

Rc4m8r06sgkbwunh5u4g Com

APTAPT 115115 Table of Contents Sparkling White Wine 1 Sparkling Rose 5 Sparkling Red Wine 7 Rose 8 White Wine 11 Skin Contact White Wine 19 Red Wine 23 Dessert and Late Harvest Wine 37 Fortified Wine 38 Beer Wine Hybrids 39 Large Format Beer and Cider 40 Sparkling White Wine Australia Alpha Box & Dice, Zaptung, Sparkling Brut South Australia $59 Glera Austria Szigeti, Osterreichischer Brut Sekt Burgenland $38 Gruner Veltliner Christoph Hoch, Kalkspitz Kamptal Sold $63Out Gruner Veltliner, Zweigelt, Sauvignon Blanc, Blauer Portugesier, Muskat Ottonel Malat, Brut Nature 2014, Furth-Palt, Kremstal $105 Chardonnay England Chapel Down, Brut NV Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Meunier $76 Ridgeview, Cavendish Brut 2014 $120 Pinot Noir, Pinot Meunier, Chardonnay Sparkling White Wine France Jean-Philippe Marchand, Le Traditionnel Cremant de Bourgogne AOC SoldSold OutOut$51 Chardonnay, Aligote Marguet, Shaman 13 2013, Champagne $135 Pinot Noir, Chardonnay Taittinger, Comtes de Champagne, Grand Cru, Blanc de Blanc 2007, Champagne $240 Chardonnay Krug, Grande Cuvee, 168 EME Edition, Brut Champagne $300 Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, Pinot Meunier Roland Champion, Grand Cru Blanc de Blancs 2012, Chouilly, Cote des Blancs, Champagne $130 Chardonnay Lallier, Collection Memoire 2002, Ay, Vallee de la Marne, Champagne Sold$195 Out Pinot Noir, Chardonnay Etienne Calsac, Blanc de Blanc Les Rocheforts, Bisseuil 1er cru, Vallee de la Marne, Champagne $150 Chardonnay Besserat de Bellefon 2006, Epernay, Vallee de la Marne, Champagne $175 Chardonnay, Pinot -

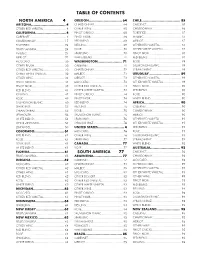

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS NORTH AMERICA 4 OREGON..........................................................................................64 CHILE..........................................................................................85 ARIZONA..........................................................................................4 CHARDONNAY..........................................................................................64 CABERNET..........................................................................................85 OTHER RED VARIETAL..........................................................................................4 OTHER WINE..........................................................................................65 CHARDONNAY..........................................................................................86 CALIFORNIA..........................................................................................4 PINOT GRIGIO..........................................................................................65 FORTIFIED..........................................................................................87 CABERNET..........................................................................................4 PINOT NOIR..........................................................................................66 MALBEC..........................................................................................87 CHARDONNAY..........................................................................................17 -

While Most Wines Are Named After a Single Grape Variety, Meritage Wines Represent the Highest Form of the Winemaker's

c/o Cosentino Signature Wineries 7415 St. Helena Highway P.O. Box 2818 Yountville, CA 94599 www.meritagewine.org Consumer, Winery Inquiries Julie Weinstock, Chairman (707) 944-1220 [email protected] Media Inquiries Jane Hodges Young Labrador Communications (707) 837-2735 [email protected] Exceptional Wines Blended in the Bordeaux Tradition While most wines are named after a single grape variety, Meritage wines represent Meritage® is a Registered Trademark. the highest form of the Exceptional Wines Blended in the Bordeaux Tradition winemaker’s art — blending. E xceptional Wines Blended in the Bordeaux Tradition ❖ What is Meritage wine? ❖ Can any blended wine be a Meritage? Meritage wines are handcrafted, red or white wines No. To obtain a license to use the Meritage name, the blended from the “noble” Bordeaux grape varieties. wine must be a blend of at least two of the traditional A Meritage wine is considered to be the very best of red or white Bordeaux grape varieties. No single grape the vintage. variety can make up more than 90% of the blend. ❖ Why was the association founded? ❖ Which grape varieties are allowed? Most wines are varietal wines, named after the grape The red “noble” Bordeaux varieties are Cabernet variety that comprises at least 75% of that wine. For Sauvignon, Merlot, Cabernet Franc, Malbec, Petit example, a “Cabernet Sauvignon” labeled as such must Verdot, and the rarer St. Macaire, Gros Verdot and be made from 75%-100% Cabernet Sauvignon grapes. Carmenère. Many winemakers, however, believe the 75% varietal The white “noble” Bordeaux varieties are Sauvignon requirement does not necessarily result in the highest Blanc, Sémillon and the rarer Sauvignon Vert.