Oral History Interview with Jacob Lawrence, 1968 October 26

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black History Month February 2020

BLACK HISTORY MONTH FEBRUARY 2020 LITERARY FINE ARTS MUSIC ARTS Esperanza Rising by Frida Kahlo Pam Munoz Ryan Frida Kahlo and Her (grades 3 - 8) Animalitos by Monica Brown and John Parra What Can a Citizen Do? by Dave Eggers and Shawn Harris (K-2) MATH & CULINARY HISTORY SCIENCE ARTS BLACK HISTORY MONTH FEBRUARY 2020 FINE ARTS Alma Thomas Jacob Lawrence Faith Ringgold Alma Thomas was an Faith Ringgold works in a Expressionist painter who variety of mediums, but is most famous for her is best-known for her brightly colored, often narrative quilts. Create a geometric abstract colorful picture, leaving paintings composed of 1 or 2 inches empty along small lines and dot-like the edge of your paper marks. on all four sides. Cut colorful cardstock or Using Q-Tips and primary Jacob Lawrence created construction paper into colors, create a painted works of "dynamic squares to add a "quilt" pattern in the style of Cubism" inspired by the trim border to your Thomas. shapes and colors of piece. Harlem. His artwork told stories of the African- American experience in the 20th century, which defines him as an artist of social realism, or artwork based on real, modern life. Using oil pastels and block shapes, create a picture from a day in your life at school. What details stand out? BLACK HISTORY MONTH FEBRUARY 2020 MUSIC Creating a Music important to blues music, and pop to create and often feature timeless radio hits. Map melancholy tales. Famous Famous Motown With your students, fill blues musicians include B.B. -

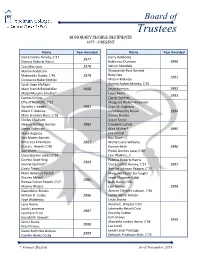

Honorary Degree Recipients 1977 – Present

Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Claire Collins Harvey, C‘37 Harry Belafonte 1977 Patricia Roberts Harris Katherine Dunham 1990 Toni Morrison 1978 Nelson Mandela Marian Anderson Marguerite Ross Barnett Ruby Dee Mattiwilda Dobbs, C‘46 1979 1991 Constance Baker Motley Miriam Makeba Sarah Sage McAlpin Audrey Forbes Manley, C‘55 Mary French Rockefeller 1980 Jesse Norman 1992 Mabel Murphy Smythe* Louis Rawls 1993 Cardiss Collins Oprah Winfrey Effie O’Neal Ellis, C‘33 Margaret Walker Alexander Dorothy I. Height 1981 Oran W. Eagleson Albert E. Manley Carol Moseley Braun 1994 Mary Brookins Ross, C‘28 Donna Shalala Shirley Chisholm Susan Taylor Eleanor Holmes Norton 1982 Elizabeth Catlett James Robinson Alice Walker* 1995 Maya Angelou Elie Wiesel Etta Moten Barnett Rita Dove Anne Cox Chambers 1983 Myrlie Evers-Williams Grace L. Hewell, C‘40 Damon Keith 1996 Sam Nunn Pinkie Gordon Lane, C‘49 Clara Stanton Jones, C‘34 Levi Watkins, Jr. Coretta Scott King Patricia Roberts Harris 1984 Jeanne Spurlock* Claire Collins Harvey, C’37 1997 Cicely Tyson Bernice Johnson Reagan, C‘70 Mary Hatwood Futrell Margaret Taylor Burroughs Charles Merrill Jewel Plummer Cobb 1985 Romae Turner Powell, C‘47 Ruth Davis, C‘66 Maxine Waters Lani Guinier 1998 Gwendolyn Brooks Alexine Clement Jackson, C‘56 William H. Cosby 1986 Jackie Joyner Kersee Faye Wattleton Louis Stokes Lena Horne Aurelia E. Brazeal, C‘65 Jacob Lawrence Johnnetta Betsch Cole 1987 Leontyne Price Dorothy Cotton Earl Graves Donald M. Stewart 1999 Selma Burke Marcelite Jordan Harris, C‘64 1988 Pearl Primus Lee Lorch Dame Ruth Nita Barrow Jewel Limar Prestage 1989 Camille Hanks Cosby Deborah Prothrow-Stith, C‘75 * Former Student As of November 2019 Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Max Cleland Herschelle Sullivan Challenor, C’61 Maxine D. -

Nytimes Black History Month Is a Good Excuse for Delving Into Our

Black History Month Is a Good Excuse for Delving Into Our Art An African-American studies professor suggests ways to mark the month, from David Driskell’s paintings and Dance Theater of Harlem’s streamed performances to the rollicking return of “Queen Sugar.” David Driskell’s “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” (1972), acrylic on canvas. Estate of David C. Driskell and DC Moore Gallery By Salamishah Tillet • Feb. 18, 2021 Black History Month feels more urgent this year. Its roots go back to 1926, when the historian Carter G. Woodson developed Negro History Week, near the February birthdays of both President Abraham Lincoln and the abolitionist Frederick Douglass, in the belief that new stories of Black life could counter old racist stereotypes. Now in this age of racial reckoning and social distancing, our need to connect with each other has never been greater. As a professor of African-American studies, I am increasingly animated by the work of teachers who have updated Woodson’s goal for the 21st century. Just this week, my 8- year-old daughter showed me a letter written by her entire 3rd-grade art class to Faith Ringgold, the 90-year-old African-American artist. And my son told me about a recent pre-K lesson on Ruby Bridges, the first African-American student who, at 6, integrated an elementary school in the South. Suddenly, the conversations my kids have at home with my husband and me are the ones they’re having in their classrooms. It's not just their history that belongs in all these spaces, but their knowledge, too. -

Art-Related Archival Materials in the Chicago Area

ART-RELATED ARCHIVAL MATERIALS IN THE CHICAGO AREA Betty Blum Archives of American Art American Art-Portrait Gallery Building Smithsonian Institution 8th and G Streets, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20560 1991 TRUSTEES Chairman Emeritus Richard A. Manoogian Mrs. Otto L. Spaeth Mrs. Meyer P. Potamkin Mrs. Richard Roob President Mrs. John N. Rosekrans, Jr. Richard J. Schwartz Alan E. Schwartz A. Alfred Taubman Vice-Presidents John Wilmerding Mrs. Keith S. Wellin R. Frederick Woolworth Mrs. Robert F. Shapiro Max N. Berry HONORARY TRUSTEES Dr. Irving R. Burton Treasurer Howard W. Lipman Mrs. Abbott K. Schlain Russell Lynes Mrs. William L. Richards Secretary to the Board Mrs. Dana M. Raymond FOUNDING TRUSTEES Lawrence A. Fleischman honorary Officers Edgar P. Richardson (deceased) Mrs. Francis de Marneffe Mrs. Edsel B. Ford (deceased) Miss Julienne M. Michel EX-OFFICIO TRUSTEES Members Robert McCormick Adams Tom L. Freudenheim Charles Blitzer Marc J. Pachter Eli Broad Gerald E. Buck ARCHIVES STAFF Ms. Gabriella de Ferrari Gilbert S. Edelson Richard J. Wattenmaker, Director Mrs. Ahmet M. Ertegun Susan Hamilton, Deputy Director Mrs. Arthur A. Feder James B. Byers, Assistant Director for Miles Q. Fiterman Archival Programs Mrs. Daniel Fraad Elizabeth S. Kirwin, Southeast Regional Mrs. Eugenio Garza Laguera Collector Hugh Halff, Jr. Arthur J. Breton, Curator of Manuscripts John K. Howat Judith E. Throm, Reference Archivist Dr. Helen Jessup Robert F. Brown, New England Regional Mrs. Dwight M. Kendall Center Gilbert H. Kinney Judith A. Gustafson, Midwest -

African American Creative Arts Dance, Literature, Music, Theater, and Visual Art from the Great Depression to Post-Civil Rights Movement of the 1960S

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 6, No. 2; February 2016 African American Creative Arts Dance, Literature, Music, Theater, and Visual Art From the Great Depression to Post-Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s Dr. Iola Thompson, Ed. D Medgar Evers College, CUNY 1650 Bedford Ave., Brooklyn, NY 11225 USA Abstract The African American creative arts of dance, music, literature, theater and visual art continued to evolve during the country’s Great Depression due to the Stock Market crash in 1929. Creative expression was based, in part, on the economic, political and social status of African Americans at the time. World War II had an indelible impact on African Americans when they saw that race greatly affected their treatment in the military while answering the patriotic call like white Americans. The Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s had the greatest influence on African American creative expression as they fought for racial equality and civil rights. Artistic aesthetics was based on the ideologies and experiences stemming from that period of political and social unrest. Keywords: African American, creative arts, Great Depression, WW II, Civil Rights Movement, 1960s Introduction African American creative arts went through several periods of transition since arriving on the American shores with enslaved Africans. After emancipation, African characteristics and elements began to change as the lifestyle of African Americans changed. The cultural, social, economic, and political vicissitudes caused the creative flow and productivity to change as well. The artistic community drew upon their experiences as dictated by various time periods, which also created their ideologies. During the Harlem Renaissance, African Americans experienced an explosive period of artistic creativity, where the previous article left off. -

Edith Halpert & Her Artists

Telling Stories: Edith Halpert & Her Artists October 9 – December 18, 2020 Charles Sheeler (1883-1965), Home Sweet Home, 1931, conte crayon and watercolor on paper, 11 x 9 in. For Edith Halpert, no passion was merely a hobby. Inspired by the collections of artists like Elie Nadelman, Robert Laurent, and Hamilton Easter Field, Halpert’s interest in American folk art quickly became a part of the Downtown Gallery’s ethos. From the start, she furnished the gallery with folk art to highlight the “Americanness” of her artists. Halpert stated, “the fascinating thing is that folk art pulls in cultures from all over the world which we have utilized and made our own…the fascinating thing about America is that it’s the greatest conglomeration” (AAA interview, p. 172). Halpert shared her love of folk art with Charles Sheeler and curator Holger Cahill, who was the original owner of this watercolor, Home Sweet Home, 1931. The Sheelers filled their home with early American rugs and Shaker furniture, some of which are depicted in Home Sweet Home, and helped Halpert find a saltbox summer home nearby, which she also filled with folk art. As Halpert recalled years later, Sheeler joined her on trips to Bennington cemetery to look at tombstones she considered to be the “first folk art”: I used to die. I’d go to the Bennington Cemetery. Everybody thought I was a queer duck. People used to look at me. That didn’t bother me. I went to that goddamn cemetery, and I went to Bennington at least four times every summer…I’d go into that cemetery and go over those tombstones, and it’s great sculpture. -

A Finding Aid to the Charles Henry Alston Papers, 1924-1980, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Charles Henry Alston Papers, 1924-1980, in the Archives of American Art Jayna M. Hanson Funding for the digitization of this collection was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art August 2008 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical Note............................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Biographical Information, 1924-1977........................................................ 5 Series 2: Correspondence, 1931-1977.................................................................... 6 Series 3: Commission and Teaching Files, 1947-1976........................................... -

Oral History Interview with Edith Gregor Halpert, 1965 Jan. 20

Oral history interview with Edith Gregor Halpert, 1965 Jan. 20 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Interview HP: HARLAN PHILLIPS EH: EDITH HALPERT HP: We're in business. EH: I have to get all those papers? HP: Let me turn her off. EH: Let met get a package of cigarettes, incidentally. [Looking over papers, correspondence, etc.] This was the same year, 1936. I quit in September. I was in Newtown; let's see, it must have been July. In those days, I had a four months vacation. It was before that. Well, in any event, sometime probably in late May, or early in June, Holger Cahill and Dorothy Miller, his wife -- they were married then, I think -- came to see me. She has a house. She inherited a house near Pittsfield, Massachusetts, and on the way back they stopped off and very excited that through Audrey McMahon he was offered a job to take charge of the WPA in Washington. He was quite scared because he had never been in charge of anything. He worked by himself as a PR for the Newark Museum for many years, and that's all he did. He sent out publicity releases that Dana gave him, or Miss Winsor, you know, told him what to say, and he was very good at it. He also got the press. -

Oral History Interview with Katherine Schmidt, 1969 December 8-15

Oral history interview with Katherine Schmidt, 1969 December 8-15 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Katherine Schmidt on December 8 & 16, 1969. The interview took place in New York City, and was conducted by Paul Cummings for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview DECEMBER 8, 1969 [session l] PAUL CUMMINGS: Okay. It's December 8, 1969. Paul Cummings talking to Katherine Schubert. KATHERINE SCHMIDT: Schmidt. That is my professional name. I've been married twice and I've never used the name of my husband in my professional work. I've always been Katherine Schmidt. PAUL CUMMINGS: Well, could we start in 0hio and tell me something about your family and how they got there? KATHERINE SCHMIDT: Certainly. My people on both sides were German refugees of a sort. I would think you would call them from the troubles in Germany in 1848. My mother's family went to Lancaster, Ohio. My father's family went to Xenia, Ohio. When my father as a young man first started out in business and was traveling he was asked to go to see an old friend of his father's in Lancaster. And there he met my mother, and they were married. My mother then returned with him to Xenia where my sister and I were born. -

July 1954 in THIS ISSUE on the Cover Letters 2 Calendar 3 Current News 4

July 1954 IN THIS ISSUE On the Cover Letters 2 Calendar 3 Current News 4 The Commencement Season • New Members of Atlanta University’s Board of Trustees • Tower Clock and Chimes for l niversity Campus • Colleges Unite to Emphasize Religion • The University Women’s Club Honors the Trustees * Three Are First-Time Winners at Art Show • The Field Workshop in Teaching the Language Arts • The Institute on Supervision • Sir Roger Makins Visits Campus • Nine Foreign Students Seek Advanced Degrees • University Plays Host to College Seniors • Academic Appointments and Promotions • Liberian Visitors Are Guests at Luncheon • Specialists in Librarianship on Faculty * The University-State Program for Supervising Teachers • The University Women 18 Whittaker Resigns 23 Quote and Unquote 28 Faculty Items 30 Alumni News 32 THE NEW ANNA A. HAASS TOWER CLOCK AND Alumni Association Activities 37 CHIMES Requiescat en Pace 39 (SEE STORY ON PAGE 7) Letters St. Louis, Missouri Boston, Massachusetts tribution from about 1930 to 1940. May 14, 1954 Their interest and support were with¬ May 16, 1954 Dear Mr. Clement: drawn just as Negro artists were be¬ In Dear President Clement: acknowledging the receipt of coming competitive and were begin¬ your letter of May 10, I would like to Your letter of May 10 with en¬ ning to distinguish themselves. extend my very sincere thanks to you, closed award has been received. the exhibition committee, and the dis¬ There have been sporadic efforts tinguished jury, for the coveted John Needless to say I am much pleased. from other sources during the past It is Hope Purchase Award. -

Faces of the League Portraits from the Permanent Collection

THE ART STUDENTS LEAGUE PRESENTS Faces of the League Portraits from the Permanent Collection Peggy Bacon Laurent Charcoal on paper, 16 ¾” x 13 ¾” Margaret Frances "Peggy" Bacon (b. 1895-d. 1987), an American artist specializing in illustration, painting, and writing. Born in Ridgefield, Connecticut, she began drawing as a toddler (around eighteen months), and by the age of 10 she was writing and illustrating her own books. Bacon studied at the Art Students League from 1915-1920, where her artistic talents truly blossomed under the tutelage of her teacher John Sloan. Artists Reginald Marsh and Alexander Brook (whom she would go on to marry) were part of her artistic circle during her time at the League. Bacon was famous for her humorous caricatures and ironic etchings and drawings of celebrities of the 1920s and 1930s. She both wrote and illustrated many books, and provided artworks for many other people’s publications, in addition to regularly exhibiting her drawings, paintings, prints, and pastels. In addition to her work as a graphic designer, Bacon was a highly accomplished teacher for over thirty years. Her works appeared in numerous magazine publications including Vanity Fair, Mademoiselle, Harper’s Bazaar, Vogue, Dial, the Yale Review, and the New Yorker. Her vast output of work included etchings, lithographs, and her favorite printmaking technique, drypoint. Bacon’s illustrations have been included in more than 64 children books, including The Lionhearted Kitten. Bacon’s prints are in the collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Museum of Modern Art, all in New York. -

Romare Bearden: the Prevalence of Ritual Introductory Essay by Carroll Greene

Romare Bearden: the prevalence of ritual Introductory essay by Carroll Greene Author Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.) Date 1971 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art ISBN 0870702513 Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2671 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art ROMARE BEARDEN: THE PREVALENCEOF RITUAL "W * . .. ROMARE BEARDEN: INTRODUCTORY ESSAYBY CARROLL GREENE THE PREVALENCEOF RITUAL THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK TRUSTEES OF THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART ACKNOWLEDGMENTS David Rockefeller, Chairman; Henry Allen Moe, John Hay This exhibition has required the cooperation of many per Whitney, Gardner Cowles, Vice Chairmen; William S. Paley, sons, and I am most grateful for their assistance. I wish to President; James Thrall Soby, Mrs. Bliss Parkinson, Vice express my appreciation first to Romare Bearden, who Presidents; Willard C. Butcher, Treasurer; Robert O. Ander spent countless hours in conversation with me concerning son, Walter Bareiss, Robert R. Barker, Alfred H. Barr, Jr.,* his life and work, which this exhibition celebrates. His Mrs. Armand P. Bartos, William A. M. Burden, J. Frederic generosity in supplying information and documentary Byers III, Ivan Chermayeff, Mrs. Kenneth B. Clark, Mrs. W. material cannot be measured. Murray Crane,* John de Menil, Mrs. C. Douglas Dillon, Members of The Museum of Modern Art staff have been Mrs. Edsel B. Ford, Gianluigi Gabetti, George Heard Hamil especially generous and helpful in executing important ton, Wallace K.