The Strange Silence of Political Theory. Response.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 North American Critical Theory After Postmodernism

Notes 1 North American Critical Theory after Postmodernism 1. I use postmodernism to mark a point, c. 1980, after which it was necessary for critical theorists, in their engagement of contemporary ideas, to address the thesis of postmodernity as it was represented in the ideas of scholars such as Lyotard and Baudrillard. This period includes authors such as Foucault and Derrida, but I do not use postmodernism as a descriptor of their ideas. I use post- structuralism to distinguish Foucault and Derrida, whose ideas were being debated at the same time as the ‘postmodern turn,’ but which I would not classify as ‘postmodern.’ Thus, by ‘after postmodernism,’ I merely mean after the ‘postmodern’ turn had been declared and thus the point after which this generation of critical theorists began to critically engage the idea. This is briefly discussed in Fraser’s interview, where she prompts me to clarify my use of the word. 2. Peter Beilharz, introduction to Postwar American Critical Thought (Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2006), xxxi. 3. Philip Wexler, preface to Critical Theory Now (New York: Falmer Press, 1991), viii. 4. Göran Therborn, From Marxism to Post-Marxism? (London and New York: Verso, 2008). 5. Therborn, From Marxism to Post-Marxism?, 105. 6. Robert J. Antonio, ‘The Origin, Development, and Contemporary Status of Critical Theory,’ Sociological Quarterly 24, 3 (1983): 342. 7. See Jules Townshend, ‘Laclau and Mouffe’s Hegemonic Project: The Story So Far,’ Political Studies 52, 6 (2004). 8. Chantal Mouffe, ‘Deliberative Democracy or Agonistic Pluralism,’ Social Research 66, 3 (Fall 1999). 9. Nancy Fraser, ‘A Future for Marxism,’ New Politics 6, 4 (1998): 95. -

1. 2. Students Will Be Able to Explain Two Research Hypotheses That Are Associated with Two Perspectives in Contemporary Theory;

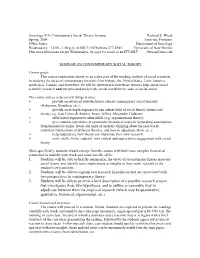

Sociology 514: Contemporary Social Theory Seminar Richard L. Wood Spring, 2009 Associate Professor Office hours: Department of Sociology Wednesdays: 12:00 - 1:00 p.m. in SSCI #1078 phone 277-3945 University of New Mexico Plus most afternoons except Wednesdays, by appt via email or at 277-1117 [email protected] SEMINAR ON CONTEMPORARY SOCIAL THEORY Course goals: This course emphasizes theory as an active part of the working toolbox of social scientists. In studying the ideas of contemporary theorists from Europe, the United States, Latin America, south Asia, Canada, and elsewhere, we will be interested in how those theories help orient social scientific research and interpret and analyze the social world for the sake of social action. The course strives to do several things at once: $ provide an advanced introduction to salient contemporary social theorists (Habermas, Bourdieu, etc.); $ provide an in-depth exposure to one salient field of social theory (democratic theory: e.g. Jean Cohen & Andrew Arato, Jeffrey Alexander, Giddens); $ offer initial exposure to other fields (e.g. organizational theory); $ give students experience in systematic theoretical analysis (separating assumptions from theoretical claims; levels and units of analysis; thinking about the real-world, empirical implications of different theories, and how to adjudicate them; etc.); $ help students see how theory can illuminate their own research; $ most vitally, foster students’ own critical and appreciative engagement with social theory More specifically, students should emerge from the course with both more complex theoretical orientation to underlie your work and some specific skills: 1. Students will be able to briefly summarize the views of several major figures in recent social theory, and identify some implications or insights of their work, relevant to the student’s own interests; 2. -

1 Populism, Constitutional Courts and Civil Society1 Andrew Arato

Populism, Constitutional Courts and Civil Society1 Andrew Arato, November- December 2018 Introduction The antagonism of populist governments to apex courts is, as I will show, a matter of historical record. It started with Peronism, the first time that an openly populist movement established its own government.2 In section 1 below I will summarize current efforts by dominant executives to pack and disempower supreme and constitutional courts in Peru, Russia, Venezuela, Israel, Hungary, Turkey and Poland. After a preliminary definition of populism in section 2, I will consider, in the next section, the reasons why populist movements once in government attack the independence of apex courts. I will argue that such an effort is a key indication of populism in government moving toward establishing itself as a regime. I will next try to summarize the harm involved in these cases to constitutional democracy. In the final fourth section, using the examples of Poland and the United States, I will maintain that the way to oppose populist authoritarianism and its attack on courts requires a strategy that is both legal and political, based on the mutual support of associations and initiatives of civil society and courts. I will argue that such an effort requires facing the democratic deficit of liberal representative democracy, and reliance on an alternative conception, namely the “plurality of democracies.” I. Admittedly, no current populist government has gone as far Peron’s in 1947 when he has initiated the impeachment and trial of 4 out of 5 Supreme Court justices, with one of them resigning before impeachment succeeded.3 As indicated by the table below, removal and/or packing are only two of the possible forms of bringing a court under government control. -

Constitution Making and Transitional Politics in Hungary © Copyright By

13 Constitution Making and Transitional Politics in Hungary Andrew Arato and Zoltán Miklósi ore than a dozen years and five amendment rule of the old regime, a rule general elections after the end of that survives to this day.1 More important, it its old regime, Hungary has a lib- was a product of a process, in common with Meral democratic constitution that established a five other countries—Poland, Czechoslova- foundation for its relatively well-functioning kia, the German Democratic Republic, Bul- parliamentary political system. The process garia, and the Republic of South Africa2—in of constitution making was entirely peaceful, which the terms of the political transition © Copyrightwas within established legality, by and the never Endowmentfrom forms of authoritarian rule ofwere de- involved the danger of dual power, civil war, veloped through roundtable negotiations. or state or popular violence. As one political On a comparative and theoretical level, the theregime, United a Soviet-type dictatorship, States was fully InstituteHungarian case represents of Peacean incomplete replaced by another, liberal democracy, the model of democratic constitution making; it destructive logic of friend and enemy well could be characterized as postsovereign with known from the history of revolutions— respect to the ideals of the American and purges, proscription, massive denial of rights, French revolutions. Characteristically, in this and terror—was avoided. Since 1989, the model, constitutions are drafted in a process main political antagonists under the old of several stages, during which no institution regime have functioned on the political if or representative body can claim to represent not always the rhetorical level as opponents fully, in an unlimited fashion, the sovereign within a competitive multiparty democracy. -

ANTONIO CARLO: the Socio-Economic Nature of the USSR

ANTONIO CARLO: The Socio-Economic Nature of the USSR BURGHART SCHMIDT: The Politics of Epistemology ERNST BLOCH: Causality and Finality 21 ANDREW ARATO: The Neo-Idealist Defense of Subjectivity HANS-JUERGEN KRAHL: Adorno's Political Contradiction JAMES SCHMIDT: Critical Theory and Sociology of Knowledge: Reply to Jay CLAUDE LEFORT: What Is Bureaucracy?* JOSE BAPTISTA: Bureaucracy and Society VINCENT DINORCIA: Critical Theory and Ecology 22 HELMUT DAHMER: Brecht and Stalinism MARTIN JAY: Crutches vs. Stilts: An Answer to Schmidt IVAN SVITAK: Illusions of Czech Socialist Democracy RUSSELL J ACOBY: Politics of the Crisis Theory A J. UEHM: Franz Kafka in Eastern Europe 23 KAREL KOSHC: HaSek and Kafka MORTON SCHOOLMAN: Marcuse's 'Second Dimension' CORNELIUS CASTORIADIS: An Interview A J. LJEHM: Intellectuals and the New Social Contract JAMES SCHMIDT: Lukics" Concept of Proletarian Bflduog JUERGEN HABERMAS: Moral Development and Ego Identity GIACOMO MARRAMAO: PoUUcal Economy and Critical Theory 24 G A. ULMEN: Wittfogel's Science of Society RICHARD W1NF1ELD: The Dilemma of Labor ROBERT D*AMIC0: Comments on Jacoby's Social Amnesia JEAN COHEN: False Premises GIAN ENRICO RUSCONI: Marxism in West Germany MUELLER & NEUSUESS: The Illusion of State Socialism JUERGEN HABERMAS: Reply to MueUer and Neusuess 25 CLAUS OFFE: Further Comments on MueUer and Neusuess ISTV AN MESZAROS: Phases of Sartre's Development CHRISTIAN LENHARDT: Anamnestic Solidarity SANDOR RADNOTI: Bloch and Lukics ALVIN W. GOULDNER; Prologue to a Theory of Revolutionary Intellectuals KARL KORSCH: Ten Theses on Marxism (1950) PAUL BREBVES: Korsch's 'Road to Marx' PAUL MATTICK: Anti-Bolshevist Communism in Germany 26 DOUGLAS KELLNER: Korsch's Revolutionary Historicism LEONARDO CEPPA: Korsch's Marxism OSKAR NEGT: The Problem of Constitution in Korsch GIACOMO MARRAMAO: Crisis and Constitution FURIO CERUTTI: Hegel. -

Andrew Arato

Canadian Journal of Political and Social Theory/Revue canadienne de theorie politique et sociale, Vol. 7, Nos. 1-2 . (River/Printemps, 1983). IMMANENT CRITIQUE AND AUTHORITARIAN SOCIALISM Andrew Arato Is a critical social theory of authoritarian state socialism, one not apologetic for any contemporary form of domination, possible at all? The question and the theoretical efforts to which it is relevant have two identifiable origins, one Western and the other Eastern European . Born as a set of efforts to understand in a practical and meaningful way the forms of domination characteristic of our epoch, the critical theory of the Frankfurt School-the Western contribution-is today apparently exhausted . Aside from a whole series of brilliant analyses of German fascism, as well as a number of imposing studies concentrating on the cultural sphere of late capitalism, the older critical theory in New York and Frankfurt, I do not believe, has ever fulfilled its self-defined social-theoretical tasks. And while,the newer critical theory in Frankfurt and Starnberg had at its highest point developed the foundations for a sophisticated, many-strata conflict model of the legitimation crisis of late capitalism, the representative product of this type of analysis contained some partially hidden doubts about the possibility of critical theory in the sense of immanent social criticism . Subsequently, the factual antinomy of practical philosophy and evolutionary social science in the work of Habermas (and his colleagues) expressed the new embarrassment of this tradition in a far more serious way than did his few increasingly sceptical remarks concerning the chances of an immanent critique with a communicative, practical relation to its audience . -

Democracy and Deliberation Tuesdays 16:00-18:00, Seminarhaus 4.103

Modules: PW-MA-2a,3a,4a; Goethe-Universität Frankfurt PT-MA-1; PT-MA-3; PT-MA-7 Sommersemester 2018 (Updated 26 April 2018) Democracy and Deliberation Tuesdays 16:00-18:00, Seminarhaus 4.103 instructor: Brian Milstein, Ph.D. email: [email protected] office: Clustergebäude “Normative Orders” Max-Horkheimer-Straße 2, Raum 3.15 60323 Frankfurt am Main office hours: Thursdays 15:00-16:00 or by appointment The Main Idea Over the past several decades, “deliberative democracy” has emerged as a major paradigm in contemporary democratic theory. Its core premise is that the essence of democracy ultimately lies not in voting and elections but in the way citizens generate a public will through active discussion and debate. Many have found this theory appealing, but it is not without its critics. And there remain many questions about how one goes about making a democracy more “deliberative.” In this seminar, we will eXamine major statements on deliberative democracy, with special attention to the approach laid out by Jürgen Habermas in Between Facts and Norms. We will consider some of the criticisms of deliberative democracy, and we will also eXplore proposals and strategies for putting deliberative theory into practice. In addition to Habermas, readings may be drawn from John Rawls, Iris Marion Young, Chantal Mouffe, Bonnie Honig, John Dryzek, Baobang He, Jane Mansbridge, Lea Ypi, Jonathan White, and others. Progress and Assessment Attendance: Everyone is responsible for attending all classes, keeping up with the weekly readings, and participating actively in our discussions. It is expected that you will not miss more than 2 sessions during the semester. -

The Possibilities and Limits of Democracy in Late Modernity

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: BECAUSE WE WILL IT: THE POSSIBILITIES AND LIMITS OF DEMOCRACY IN LATE MODERNITY Lawrence James Olson, Doctor of Philosophy, 2006 Dissertation directed by: Professor Vladimir Tismaneanu Department of Government and Politics Cornelius Castoriadis’ life can be characterized as one of engaged dissent. As a founding member of the Socialisme ou Barbarie group in France, Castoriadis maintained a consistent position as an opponent of both Western capitalism and Soviet totalitarianism during the Cold War. This position also placed Castoriadis in opposition to the mainstream French left, particularly Jean-Paul Sartre, who supported the French Communist Party and defended the Soviet Union. After the dissolution of the group, Castoriadis continued to assert the possibility of constructing participatory democratic institutions in opposition to the existing bureaucratic capitalist institutional structure in the Western world. The bureaucratic-capitalist institutional apparatus of the late modern era perpetuates a system where the individual is increasingly excluded from the democratic political process and isolated within the private sphere. However, the private sphere is not a refuge from the intrusion of the bureaucratic-capitalist imaginary, which consistently seeks to subject the whole of society to rational planning. Each individual is shaped by his relationship to the bureaucracy; on the one hand, his relationships with other become subjected to an instrumental calculus, while at the same time, the individual seeks to find some meaning for the world around him by turning to the private sphere. Furthermore, a crisis of meaning pervades late modern societies, where institutions are incapable of providing answers to the questions posed to them by individuals living in these societies. -

Democracy and Civil Society. Outlines of a New Paradigm

DEMOCRACY AND CIVL SOCIETY: OUTLINES OF A NEW PARADIGM BY FERENC MISZLIVETZ Evaluating 1989 has divided analysts from the outset. The majority of political scientists and sociologists saw the events as the victory of liberal democracy in Central and Eastern Europe. Thus, Jürgen Habermas or Timothy Garton Ash did not see the ‘velvety revolutions’ as offering anything new, they did not believe that any original or innovative idea appeared or even became institutionalized during the ‘velvety revolutions’. According to this view, 1989 simply set things right and if we can talk of revolutions at all, even in the best of cases this is the process they served („nachholende Revolution”, or „rectifying revolution”)1 Others, like Andrew Arato, hold a sharply divergent opinion. They believe that 1989 had a radically new message within the field of democracy and civil society.2 I myself share the view that the meaning and message of ’89 places the previous history of Central European and European democracies in a very new framework and sheds a new light on them, and also opens new perspectives for the future on the global level. This is true even if the results which the transition processes of the Eastern and Central European countries have produced over the past two decades have not met with the expectations and plans of the supporters and activists of the democratic transformation. The contrast is particularly sharp if we compare results to the opportunities which arose on the regional, the European and the global level when the Berlin wall went down and the iron curtain ceased to exist. -

Download PDF (82.8

Contributors Gavin W. Anderson is a Senior Lecturer at the School of Law, University of Glasgow, having previously taught at the University of Warwick. He undertook graduate studies at Osgoode Hall Law School, and the University of Toronto. In 2003–04, he was a Jean Monnet Fellow at the European University Institute, Florence, and he has also been a Visiting Fellow at the Centre for Comparative Constitutional Studies, University of Melbourne. His recent research focuses upon the contribution of the global South to debates on global constitutionalism, and he is the author of Constitutional Rights after Globalisation. Andrew Arato is the Dorothy Hart Hirshon Professor in Political and Social Theory at The New School. He has taught at L’Ecole des hautes études and Sciences Po in Paris, as well as at the Central European University in Budapest. Professor Arato has served as a consultant for the Hungarian Parliament on constitutional issues (1996–97), and as US State Department Democracy Lecturer and Consultant (on Constitutional issues) on Nepal (2007). He was re-appointed by the State Department in the same capacity for Zimbabwe (November 2010). Professor Arato’s scholarly research is widely recognized, and conferences and sessions have been organized around his work at University of Glasgow Law School, Koc University, Istanbul and the Faculty of Law, Witwatersrand University, Johannesburg, South Africa. He has published widely on legal and political theory, including his most recent book, Adventures of the Constituent Power (Cambridge University Press, 2017). Jean d’Aspremont is Professor of Public International Law at the University of Manchester, where he founded the Manchester International Law Centre (MILC). -

Post Sovereign Constitution-Making in Hungary: After Success, Partial Failure, and Now What? Andrew Arato

Post Sovereign Constitution-making in Hungary: After Success, Partial Failure, and Now What? Andrew Arato PART ONE The study reconstructs what the author calls the model of post sovereign constitution making, namely the multi stage, democratic model with a round table or multi party negotiations as its center piece, involving two constitutions, with a free election in between, with important role for legality and its enforcement through a constitutional court. This is the model that was more or less perfected in South Africa in the 1990s. In comparison, Hungary, the empirical object of the study is seen as an imperfect realization, because here the final stage, not provided for in the interim constitution was not completed in a democratic process. The author thus sees the role of the Hungarian Constitutional Court as compensatory, and inevitably weakening given the weak legitimating background provided for by the incomplete process. A case in point focused on by the study is the jurisprudence of constitutional amendments. In light of the inherited amendment rule, the constitution of the regime change could only be reliably protected if the Hungarian Constitutional Court adopted one or another version of amendment review, in the path of the Indian Basic structure doctrine. The study tries to show that a 4/5 rule concerning constitutional replacement adopted during an unsuccessful effort at constitution making could be a textual support for such a review. Subsequently to the writing of the study, the new right wing Hungarian parliament abolished the 4/5 rule, by using the 2/3 amending rule. This in the view of the author of the study is prima facie unconstitutional. -

Harry F. Dahms

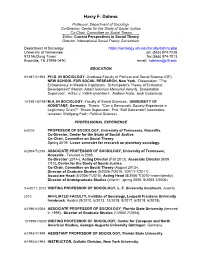

Harry F. Dahms Professor, Department of Sociology Co-Director, Center for the Study of Social Justice _ Co-Chair, Committee on Social Theory _ Editor, Current Perspectives in Social Theory Director, International Social Theory Consortium Department of Sociology https://sociology.utk.edu/faculty/dahms.php University of Tennessee ph: (865) 974-7028 913 McClung Tower fax:(865) 974-7013 Knoxville, TN 37996-0490 email: [email protected] EDUCATION 9/1987-5/1993 PH.D. IN SOCIOLOGY. Graduate Faculty of Political and Social Science (GF) NEW SCHOOL FOR SOCIAL RESEARCH, New York. Dissertation: "The Entrepreneur in Western Capitalism: Schumpeter's Theory of Economic Development" (Honor: Albert Salomon Memorial Award). Dissertation Supervisor: Arthur J. Vidich (members: Andrew Arato, José Casanova). 10/1981-8/1987 M.A. IN SOCIOLOGY. Faculty of Social Sciences. UNIVERSITY OF KONSTANZ, Germany. Thesis: "Can a Democratic Society Experience a Legitimacy Crisis?" Thesis Supervisor: Prof. Ralf Dahrendorf (secondary reviewer: Wolfgang Fach, Political Science). PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 8/2016- PROFESSOR OF SOCIOLOGY, University of Tennessee, Knoxville. Co-Director, Center for the Study of Social Justice. Co-Chair, Committee on Social Theory. Spring 2019: Leave semester for research on planetary sociology. 8/2004-7/2016 ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF SOCIOLOGY, University of Tennessee, Knoxville. Tenured in 2005. Co-Director (2014-), Acting Director (Fall 2013), Associate Director (8/09 7/13), Center for the Study of Social Justice. Co-Chair, Committee on Social Theory (August 2013-). Director of Graduate Studies (8/2006-7/2010; 1/2011-7/2011). Associate Head (8/2006-7/2010); Acting Head (8/2006-7/2010–intermittently). Director of Undergraduate Studies (interim: spring 2020; 8/2005-7/2006).