Apple Watch, Apple TV, And/Or Apple Car?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apple & Deloitte Team up to Accelerate Business

NEWS RELEASE Apple & Deloitte Team Up to Accelerate Business Transformation on iPhone & iPad 9/28/2016 Deloitte Introduces New Apple Practice to Help Businesses Design & Implement iPhone & iPad Solutions CUPERTINO, Calif. & NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Apple® and Deloitte today announced a partnership to help companies quickly and easily transform the way they work by maximizing the power, ease-of-use and security the iOS platform brings to the workplace through iPhone® and iPad®. As part of the joint effort, Deloitte is creating a first-of-its-kind Apple practice with over 5,000 strategic advisors who are solely focused on helping businesses change the way they work across their entire enterprise, from customer-facing functions such as retail, field services and recruiting, to R&D, inventory management and back-office systems. This Smart News Release features multimedia. View the full release here: http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20160928006317/en/ Apple CEO Tim Cook and Deloitte Global CEO Punit Renjen meet at Apple's campus to Apple and Deloitte will also announce a joint effort to accelerate business transformation using iOS, iPhone & iPad. collaborate on the development (Courtesy of Apple/Roy Zipstein) of a new service offering from Deloitte Consulting called EnterpriseNext, designed to help clients fully take advantage of the iOS ecosystem of hardware, software and services in the workplace. The new offering will help customers discover the highest impact possibilities within their industries and quickly develop custom solutions through rapid prototyping. 1 “We know that iOS is the best mobile platform for business because we’ve experienced the benefit ourselves with over 100,000 iOS devices in use by Deloitte’s workforce, running 75 custom apps,” said Punit Renjen, CEO of Deloitte Global. -

CCS Insight Market Forecast

Market Forecast Wearables, UK 2016-2020 April 2016 Update Content Summary of the wearables forecast Smartphone companions forecast Quantified self forecast Wearable cameras forecast Augmented reality and virtual reality forecast Wearables categorization Market Forecast: Wearables, UK, 2016-2020 © CCS Insight 2 Summary of the Wearables Forecast Market Forecast: Wearables, UK, 2016-2020 © CCS Insight 3 Forecast Coverage CCS Insight's forecast currently covers four main categories of wearable devices: smartphone companions, quantified self, wearable cameras and augmented and virtual reality (AR and VR). – The other categories are at a very early stage of development. For detailed segmentation, please see pages 59-68. Each category is forecast in three scenarios: core, low and high, as the market is still young and has an elevated level of uncertainty. – The core scenario describes the most likely outcome across all categories, given our current understanding. – A change in one category can trigger changes in other categories. The summary presents the core scenario for all four categories. – Low and high scenarios for the different categories cannot be added, as significant cannibalization could happen between segments — a high scenario for one is likely to mean a shift toward the low scenario of another. We have developed a split by device form in the core scenario. – This is a top-down split and subject to a significant uncertainty owing to the very early days of the market; one hugely successful product can greatly change the outlook. The sell-in value forecast is developed at a constant exchange rate of pounds to dollars from April 2016 onward. Market Forecast: Wearables, UK, 2016-2020 © CCS Insight 4 Key Messages The segmentation of wearable devices, largely unchanged since 2015, can be found on pages 59-68. -

Apple Strategy Teardown

Apple Strategy Teardown The maverick of personal computing is looking for its next big thing in spaces like healthcare, AR, and autonomous cars, all while keeping its lead in consumer hardware. With an uphill battle in AI, slowing growth in smartphones, and its fingers in so many pies, can Apple reinvent itself for a third time? In many ways, Apple remains a company made in the image of Steve Jobs: iconoclastic and fiercely product focused. But today, Apple is at a crossroads. Under CEO Tim Cook, Apple’s ability to seize on emerging technology raises many new questions. Primarily, what’s next for Apple? Looking for the next wave, Apple is clearly expanding into augmented reality and wearables with the Apple Watch AirPods wireless headphones. Though delayed, Apple’s HomePod speaker system is poised to expand Siri’s footprint into the home and serve as a competitor to Amazon’s blockbuster Echo device and accompanying virtual assistant Alexa. But the next “big one” — a success and growth driver on the scale of the iPhone — has not yet been determined. Will it be augmented reality, healthcare, wearables? Or something else entirely? Apple is famously secretive, and a cloud of hearsay and gossip surrounds the company’s every move. Apple is believed to be working on augmented reality headsets, connected car software, transformative healthcare devices and apps, as well as smart home tech, and new machine learning applications. We dug through Apple’s trove of patents, acquisitions, earnings calls, recent product releases, and organizational structure for concrete hints at how the company will approach its next self-reinvention. -

Meditative Story Transcript – Angela Ahrendts Click Here to Listen to The

Meditative Story Transcript – Angela Ahrendts Click here to listen to the full Meditative Story episode with Angela Ahrendts. ANGELA AHRENDTS: I stand mesmerized seeing this eagle soar and dive, soar and dive. At this moment it’s the strangest thing, an inner peace takes over me with each breath. I feel this sudden clarity, this deep confidence. An idea quickly builds inside of me: I am not a tree; I am not supposed to stay permanently fixed and rooted where I am. My three babies will fly the nest. They’ll be gone. The eagle is my sign in my storm. I am supposed to fly. ROAHN GUNATILLAKE: Angela Ahrendts is best known in the business world where as CEO of Burberry she turned the company around, and then stepped out of the number one position to help Apple reinvent its famous retail store environment. But the Meditative Story she shares today couldn’t be further from the high-flying worlds of fashion and technology – it’s about finding sanctuaries that we can turn to for clarity when new direction and new possibilities show up in our lives. In this series, we combine immersive first-person stories and breathtaking music with the science-backed benefits of mindfulness practice. From WaitWhat and Thrive Global, this is Meditative Story. I’m Rohan, and I’ll be your guide. The body relaxed. The body breathing. Your senses open. Your mind open. Meeting the world. AHRENDTS: With a blanket tucked beneath my arm, I head out into the backyard, basking in the warm afternoon light. -

How Do We Keep Physical Stores Relevant in the Digital Age?

STORES: WHAT NOW? How do we keep Physical Stores Relevant in the Digital Age? A State of the Industry Report By: LEE PETERSON CHRIS Executive Vice President, DOERSCHLAG Brand, Strategy & Design Chief Executive Officer 4 Winning back the storeless generation It’s a new dawn, retailers! Hope you’re ready. 6 Let’s Talk about BOPIS As we look across the fluid landscape of physical buy online, pick up in store retail today, there are four disruptors affecting every aspect of selling goods that simply must be recognized and called out. In our minds, these are the powerful 8 Customer prerequisites to being successful now and going forward into what should be the most interesting— Segmentation albeit scary—period in retail history. the advantages and limitations Let’s commiserate. 10 People Make the Difference but they need to be up to the task, and that’s up to you 12 The Omnichannel Dilemma focus or fail 15 5 Mobile Retailing Tips Live-Shop keeping pace with fast A huge shift in consumer mentality has bludgeoned the thinking of all moving consumers retailers, regardless of vertical. Shoppers, especially younger ones, no longer shop and live separately, they/we all live-shop simultaneously. One consumer told us, “I needed something, remembered it at work, shrank down what 16 Human Interaction I was doing, went online and bought it—5 minutes.” We are shopping all community and connection the time now, not within store hours and not necessarily in stores at all. Consequently, not only have retailers had to compete online, but the days of the “stack it high and let it fly” experience are over. -

A Survey of Smartwatch Platforms from a Developer's Perspective

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Technical Library School of Computing and Information Systems 2015 A Survey of Smartwatch Platforms from a Developer’s Perspective Ehsan Valizadeh Grand Valley State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cistechlib ScholarWorks Citation Valizadeh, Ehsan, "A Survey of Smartwatch Platforms from a Developer’s Perspective" (2015). Technical Library. 207. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cistechlib/207 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Computing and Information Systems at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Technical Library by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Survey of Smartwatch Platforms from a Developer’s Perspective By Ehsan Valizadeh April, 2015 A Survey of Smartwatch Platforms from a Developer’s Perspective By Ehsan Valizadeh A project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Computer Information Systems At Grand Valley State University April, 2015 ________________________________________________________________ Dr. Jonathan Engelsma April 23, 2015 ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................................ 5 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................... 6 WHAT IS A SMARTWATCH -

Apple Kicks Off Event; $1,000 Iphone Is Expected 12 September 2017, by Michael Liedtke and Barbara Ortutay

Apple kicks off event; $1,000 iPhone is expected 12 September 2017, by Michael Liedtke And Barbara Ortutay on him with joy instead of sadness." The souped-up "anniversary" iPhone, which would come a decade after Jobs unveiled the first version, could also cost twice what the original iPhone did. It would set a new price threshold for any smartphone intended to appeal to a mass market. WHAT A THOUSAND BUCKS WILL BUY Apple CEO Tim Cook kicks off the event for a new product announcement at the Steve Jobs Theater on the new Apple campus on Tuesday, Sept. 12, 2017, in Cupertino, Calif. (AP Photo/Marcio Jose Sanchez) Apple has kicked off a September product event at which it is expected to unveil a dramatically redesigned iPhone that could cost $1,000. With a photo of former Apple co-founder and CEO Steve It's the first product event Apple is holding at its Jobs projected in the background, Apple CEO Tim Cook new spaceship-like headquarters in Cupertino, kicks off the event for a new product announcement at California. Before getting to the new iPhone, the the Steve Jobs Theater on the new Apple campus, company unveiled a new Apple Watch model with Tuesday, Sept. 12, 2017, in Cupertino, Calif. (AP cellular service and an updated version of its Apple Photo/Marcio Jose Sanchez) TV streaming device. The event opened in a darkened auditorium, with only the audience's phones gleaming like stars, Various leaks have indicated the new phone will along with a message that said "Welcome to Steve feature a sharper display, a so-called OLED screen Jobs Theater." A voiceover from Jobs, Apple's co- that will extend from edge to edge of the device, founder who died in 2011, opened the event before thus eliminating the exterior gap, or "bezel," that CEO Tim Cook took stage. -

Introduction to Time Round Seite 1 Von 8

Pebble | Introduction to Time Round Seite 1 von 8 Introduction to Time Round Last Updated - Nov 09, 2015 02:40PM PST What is Pebble Time Round? How it works Compatibility Terminology Apps Pebble Settings Battery Life What is Pebble Time Round? Pebble Time Round is the latest, lightest, and thinnest customizable watch from Pebble that conveniently and subtly delivers the information that you want directly to your wrist. It connects to your iOS (running iOS8 & up) or Android (running OS 4.3 & up) smartphone via classic (Android) or low energy Bluetooth (iOS and Android) and notifies you about calls, texts, calendar events, social messages, sports scores, stocks, workout progress, and more! https://help.getpebble.com/customer/portal/articles/2135733 25.04.2016 Pebble | Introduction to Time Round Seite 2 von 8 Despite the screen always being on, Pebble Time Round lasts for up to 2 days on a single charge. It is also fast charging so that you can get a full day’s worth of power available after charging for just 15 minutes. Scratch and splash resistant for your convenience, Pebble Time Round is our most personalizable watch yet. It’s available in three colors (Silver, Black, Rose Gold), two band sizes (14mm or 20mm), with two band options (leather and metal). The latest addition to our collection is everything we loved about Pebble Time, in a smaller, more elegant package. https://help.getpebble.com/customer/portal/articles/2135733 25.04.2016 Pebble | Introduction to Time Round Seite 3 von 8 Order Now! (https://pebble.com/buy-pebble-time- round-smartwatch) Back to the Top How it Works Pebble Time Round connects by Bluetooth LE (4.0) to your iPhone or classic and Bluetooth LE to your Android device. -

Higher Ground: Rosanne Haggerty Founder and Director of Nonprofit C

Higher Ground: Rosanne Haggerty Founder and Director of Nonprofit C... http://magazine.wsj.com/hunter/donate/higher-ground/2/ More News, Quotes, Companies, Videos SEARCH Tuesday, July 6, 2010 FEATURES HUNTER GATHERER FASHION NOMAD WSJ HOT TOPICS: SOPHIE DAHL'S FAVORITE SCENTS THE GURU OF PANDORA RADIO SLOW TRAVEL LOUIS VUITTON'S LOGO DONATE JUNE 10, 2010 ET Rosanne Haggerty has found a way to use good design and business savvy to take the blight out of the city ARTICLE COMMENTS (1) WSJ. MAGAZINE HOME PAGE » 1 of 4 7/6/2010 11:16 AM Higher Ground: Rosanne Haggerty Founder and Director of Nonprofit C... http://magazine.wsj.com/hunter/donate/higher-ground/2/ Email Print Permalink + More Text Search WSJ. Magazine By Alastair Gordon When the Prince George reopened in 1999, it offered job-training counselors, health services, psychologists, therapists and even acupuncturists. “We make it easy for people to succeed,” Haggerty says. And that luxe ballroom? “We organized a job-training collaboration with four other not-for-profits who restored the space,” Haggerty says, explaining that this reduced the cost to $1.5 million. The ballroom now generates $800,000 in annual rentals. “Rosanne takes conventional wisdom and turns it on its head,” says Alexander Gorlin, an architect who designed the recently opened The Brook in the South Bronx, a housing facility built on a former cockfighting venue at 148th Street. “People on the street stop by and ask, ‘Is this a new condominium building? How do I get in?’ ” Gorlin, who is best known for designing high-end homes in the Hamptons and Manhattan, gave the shelter open-air terraces, a community vegetable garden and a shared green-roof landscape. -

Meet Dave Muffly, the Apple Campus 2 Arborist - Latimes.Com

6/11/13 Meet Dave Muffly, the Apple Campus 2 arborist - latimes.com latimes.com/business/technology/la-fi-tn-meet-dave-muffly-the-arborist-working-on-apple-campus-2- 20130606,0,3238393.story latimes.com Meet Dave Muffly, the Apple Campus 2 arborist By Chris O'Brien 5:00 AM PDT, June 7, 2013 A couple of years ago, when Steve Jobs appeared before the a d ve rti se m e n t Cupertino, Calif., City Council to discuss Apple's proposed Men: Restore your hair in as new campus, he mentioned that the company had even hired little as 4 weeks a "senior arborist" from Stanford. P rovided by WebM etro Since then, the identity of that arborist has remained a Shocking discovery for joint mystery. But no more. relief P rovided by I ns taflex Meet Dave Muffly, Apple's arborist and tree whisperer. Muffly is a well-known figure in the Silicon Valley tree What is the best non- community. Several folks I contacted were surprised that his prescription eyelash enhancer? identity had remained a secret for so long. His connection to P rovided by DermStore.c om the project was revealed through a series of documents the city of Cupertino posted on Thursday as part of the environmental review process for the project. STORY: Apple will outgrow new campus in Cupertino before it's built Muffly did not respond to a request for comment about his work. An Apple spokeswoman declined to comment. As part of his work, Muffly is overseeing one of the most audacious aspects of a project that has an epic, circular structure. -

Not for Sale

Chapter 2: Traits, Behaviors, and Relationships NOT FOR SALE YOUR LEADERSHIP CHALLENGE After reading this chapter, you should be able to: • Outline some personal traits and characteristics that are associated with effective leaders. • Identify your own traits that you can transform into strengths and bring to a leadership role. • Distinguish among various roles leaders play in organizations, including operations roles, collaborative roles, and advisory roles, and where your strengths might best fit. • Recognize autocratic versus democratic leadership behavior and the impact of each. • Know the distinction between people-oriented and task-oriented leadership behavior and when each should be used. • Understand how the theory of individualized leadership has broadened the understanding of relationships between leaders and followers. • Describe some key characteristics of entrepreneurial leaders. CHAPTER OUTLINE 47 Col. Joe D. Dowdy and Maj. Gen. Leader’s Bookshelf 36 The Trait Approach James Mattis, U.S. Marine Corps 38 Give and Take: A Revolutionary 41 Know Your Strengths 50 Denise Morrison, Campbell Soup Approach to Success 43 Behavior Approaches Company, and Michael Arring- Leadership at Work 52 Individualized Leadership ton, TechCrunch 58 Your Ideal Leader Traits 55 Entrepreneurial Traits and Leader’s Self-Insight Leadership Development: Behaviors 40 Rate Your Optimism Cases for Analysis In the Lead 47 What’s Your Leadership 58 Consolidated Products 40 Marissa Mayer, Yahoo Orientation? 60 Transition to Leadership 45 Warren Buffett, Berkshire 55 Your ‘‘LMX’’ Relationship Hathaway oon after her husband was elected the first African American president in the United States, Michelle Obama appeared on ‘‘The Tonight Show’’ wearing a S stylish outfit consisting of a pencil skirt, a yellow and brown tank top, and a mustard yellow cardigan. -

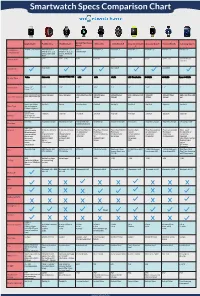

Smartwatch Specs Comparison Chart

Smartwatch Specs Comparison Chart Apple Watch Pebble Time Pebble Steel Alcatel One Touch Moto 360 LG G Watch R Sony Smartwatch Asus ZenWatch Huawei Watch Samsung Gear S Watch 3 Smartphone iPhone 5 and Newer Android OS 4.1+ Android OS 4.1+ iOS 7+ Android 4.3+ Android 4.3+ Android 4.3+ Android 4.3+ Android 4.3+ Android 4.3+ iPhone 4, 4s, 5, 5s, iPhone 4, 4s, 5, 5s, Android 4.3+ Compatibility and 5c, iOS 6 and and 5c, iOS 6 and iOS7 iOS7 Price in USD $349+ $299 $149 - $180 $149 $249.99 $299 $200 $199 $349 - 399 $299 $149 (w/ contract) May 2015 June 2015 June 2015 Availability Display Type Screen Size 38mm: 1.5” 1.25” 1.25” 1.22” 1.56” 1.3” 1.6” 1.64” 1.4” 2” 42mm: 1.65” 38mm: 340x272 (290 ppi) 144 x 168 pixel 144 x 168 pixel 204 x 204 Pixel 258 320x290 pixel 320x320 pixel 320 x 320 pixel 269 320x320 400x400 Pixel 480 x 360 Pixel 300 Screen Resolution 42mm: 390x312 (302 ppi) ppi 205 ppi 245 ppi ppi 278ppi 286 ppi ppi Sport: Ion-X Glass Gorilla 3 Gorilla Corning Glass Gorilla 3 Gorilla 3 Gorilla 3 Gorilla 3 Sapphire Gorilla 3 Glass Type Watch: Sapphire Edition: Sapphire 205mah Approx 18 hrs 150 mah 130 mah 210 mah 320 mah 410 mah 420 mah 370 mah 300 mah 300 mah Battery Up to 72 hrs on Battery Reserve Mode Wireless Magnetic Charger Magnetic Charger Intergrated USB Wireless Qi Magnetic Charger Micro USB Magnetic Charger Magnetic Charger Charging Cradle Charging inside watch band Hear Rate Sensors Pulse Oximeter 3-Axis Accelerome- 3-Axis Accelerome- Hear Rate Monitor Hear Rate Monitor Heart Rate Monitor Ambient light Heart Rate monitor Heart