Field Identification of Archilochus Hummingbirds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Occurrence of Black-Chinned Hummingbird in Alabama

RARE OCCURRENCE First occurrence of Black-chinned Bummingbirdin Alabama With notes on identification Greg D. Jackson Photo/GregD. Jackson. 178 AmericanBirds, Summer 1988 observeddunng the courseof the hum- taft-pumpingof the Black-ch•nned•s b•rd (ArchtlochusalexandrO has m•ngb•rd'sstay. The b•rd wasthe same very noticeable whfie feeding, and •s beenHEBLACK-CHINNEDreported casually from HUMMING- Florida sizeas a Ruby-throated Hummingbird. generallymore frequentand persistent (Hoffman 1983)and is an annualvisitor The bill waslonger than that of a Ruby- than that shownby the Ruby-throated to southeasternLouisiana (N. L. New- throated. The wingswere pointed, but Hummingbird (N. L. Newfield pers field pers. comm.), but until January the outermostprimary had an obtuse comm.). Immature males of either spe- 1984 had never been recorded in Ala- subterminal angulation and a broad, ciescan showsome characteristic gorget bama. Besides the breeding Ruby- blunt tip. The tail, which was pumped colorby early fall (Scott 1983). throated Hummingbird (Archilochus constantlywhile feeding,had a mod- colubris),the only other member of this eratelydeep central notch when folded, family recordedin Alabamais the Ru- and was rather square with a shallow fousHummingbird (Selasphorus rufus), notch when spread.The crown and face which is a rare visitorin migrationand weredark gray-green.There wasa short w•nter (Imhof 1976). The first docu- white stripe posterior to the eye. The mented occurrence of the Black- dorsal surface of the tail showed black ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ch•nned Hummingbird in the state is outer rectrices and dark green inner from the Spring Hill district of Mobile rectrices.The remainder of the upper- The author is grateful to Nancy L. -

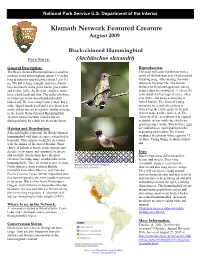

Klamath Network Featured Creature August 2009

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Klamath Network Featured Creature August 2009 Black-chinned Hummingbird FIELD NOTES: (Archilochus alexandri) General Description: Reproduction: The Black-chinned Hummingbird is a small to The male will court the female with a medium-sized hummingbird, about 3 ¼ inches series of shallow dips and a high-pitched long at maturity and weighing about 3 g or 0.1 warbling song. After mating, the male oz. The bill is long, straight, and thin. Adults returns to his loner life. The female have brilliantly shiny green backs, green sides, builds a well-camouflaged nest, taking and a white belly. As the name implies, males about 3 days to construct it. A. alexandri have a dark head and chin. The males also have nests about 4-8 feet high in a tree, often an iridescent violet throat band and a dark over water, and along a drooping or forked tail. The less conspicuous female has a forked branch. The down of young white-tipped rounded tail and a few black dots sycamore trees and other plants is on the throat instead of a patch, similar in looks woven together with spider webs and to the female Ruby-throated Hummingbird. lichens make a soft, elastic nest. The Juvenile males resemble females but are elasticity of the nest allows it to expand distinguishable by a dark streak on the throat. to double its size while the chicks are growing larger inside. Two to three eggs Habitat and Distribution: are laid between April and September, Although highly territorial, the Black-chinned depending on location. -

Dated Phylogenetic and Biogeographic Inference of Migratory Behavior in Bee Hummingbirds Yuyini Licona-Vera and Juan Francisco Ornelas*

Licona-Vera and Ornelas BMC Evolutionary Biology (2017) 17:126 DOI 10.1186/s12862-017-0980-5 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access The conquering of North America: dated phylogenetic and biogeographic inference of migratory behavior in bee hummingbirds Yuyini Licona-Vera and Juan Francisco Ornelas* Abstract Background: Geographical and temporal patterns of diversification in bee hummingbirds (Mellisugini) were assessed with respect to the evolution of migration, critical for colonization of North America. We generated a dated multilocus phylogeny of the Mellisugini based on a dense sampling using Bayesian inference, maximum- likelihood and maximum parsimony methods, and reconstructed the ancestral states of distributional areas in a Bayesian framework and migratory behavior using maximum parsimony, maximum-likelihood and re-rooting methods. Results: All phylogenetic analyses confirmed monophyly of the Mellisugini and the inclusion of Atthis, Calothorax, Doricha, Eulidia, Mellisuga, Microstilbon, Myrmia, Tilmatura,andThaumastura. Mellisugini consists of two clades: (1) South American species (including Tilmatura dupontii), and (2) species distributed in North and Central America and the Caribbean islands. The second clade consists of four subclades: Mexican (Calothorax, Doricha)and Caribbean (Archilochus, Calliphlox, Mellisuga)sheartails,Calypte,andSelasphorus (incl. Atthis). Coalescent-based dating places the origin of the Mellisugini in the mid-to-late Miocene, with crown ages of most subclades in the early Pliocene, and subsequent species splits in the Pleistocene. Bee hummingbirds reached western North America by the end of the Miocene and the ancestral mellisuginid (bee hummingbirds) was reconstructed as sedentary, with four independent gains of migratory behavior during the evolution of the Mellisugini. Conclusions: Early colonization of North America and subsequent evolution of migration best explained biogeographic and diversification patterns within the Mellisugini. -

Mecklenburg Breeding Bird Atlas

Breeding Bird Atlas of Mecklenburg County, NC Written by Donald W. Seri Breeding Bird Atlas of Mecklenburg County, NC Written by Donald W. Seri Illustrations and Layout Design by Leigh Anne Carter Technical Publication Series Number 102: October 2017 Copyright © 2017 Artwork copyright © 2017 Leigh Anne Carter Photographs used with permission and photographers retain copyright of photos All rights reserved. is book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without permission of the copyright holder(s). Published in partnership with: e Mecklenburg Audubon Society and e Mecklenburg County Park and Recreation Department Our Partners Mecklenburg Audubon Society e Mecklenburg Audubon Society was founded in 1940. e Society has been a leader in education and conservation in the Charlotte region for over 75 years. Mecklenburg County Park and Recreation Department e Mecklenburg County Park and Recreation Department was established in 1974. e Department manages over 22,000 acres of parks, greenways, and nature preserves in the county. United States Geological Survey Learn about Breeding Bird Atlas Explorer at: http://www.pwrc.usgs.gov/bba/ Table of Contents Breeding Bird Atlas 1 Red-headed Woodpecker 55 European Starling 96 Results 10 Red-bellied Woodpecker 56 Cedar Waxwing 97 Species Accounts 15 Downy Woodpecker 57 Ovenbird 98 Hairy Woodpecker 58 Worm-eating Warbler 99 Canada Goose 18 Northern Flicker 59 Louisiana Waterthrush 100 Wood Duck 19 Pileated Woodpecker 60 Black-and-white Warbler 101 Mallard 20 American Kestrel 61 Prothonotary -

Worcester County Birdlist

BIRD LIST OF WORCESTER COUNTY, MASSACUSETTS 1931-2019 This list is a revised version of Robert C. Bradbury’s Bird List of Worcester County, Massachusetts (1992) . It contains bird species recorded in Worcester County since the Forbush Bird Club began publishing The Chickadee in 1931. Included in Appendix A, and indicated in bold face on the Master List are bird Species which have been accepted by the Editorial Committee of The Chickadee, and have occurred 10 times or fewer overall, or have appeared fewer than 5 times in the last 20 years in Worcester County. The Editorial Committee has established the following qualifying criteria for any records to be considered of any record not accepted on the Master List: 1) a recognizable specimen 2) a recognizable photograph or video 3) a sight record corroborated by 3 experienced observers In addition, any Review Species with at least one accepted record must pass review of the Editorial Committee of the Chicka dee. Any problematic records which pass review by the Chickadee Editorial Committee, but not meeting the three first record rules above, will be carried into the accepted records of the given species. Included in Appendix B are records considered problematic. Problematic species either do not meet at least one of the qualifying criteria listed above, are considered likely escaped captive birds, have arrived in Worcester County by other than self-powered means, or are species not yet recognized as a count able species by the Editorial Committee of The Chickadee . Species names in English and Latin follow the American Ornithologists’ Union Checklist of North American Birds, 7 th edition, 59th supplement, rev. -

Ruby-Throated Hummingbird (Archilochus Colubris) Allen T

Ruby-throated Hummingbird (Archilochus colubris) Allen T. Chartier Washtenaw Co., MI 7/5/2006 © Allen Chartier This species sponsored in memory of Ginny Merlotti. (Click to view a comparison of Atlas I to II) Buzzing wings, strident sputtering calls, and a Ontario, it is common throughout the southern portions of the province north to the north shore flash of green and red; virtually anyone can of Lake Superior, having expanded northward recognize our smallest bird, the Ruby-throated somewhat between their two atlas periods Hummingbird. Its combative demeanor and (Cadman et al. 1987, Cadman et al. 2007). aerobatic flight has endeared it to thousands of homeowners who have placed feeders out for In Michigan, Ruby-throated Hummingbirds them in ever increasing numbers. This is the were considered a common breeding species in only breeding hummingbird species throughout the LP but relatively rare in the UP by Wood eastern North America, ranging from the (1951) and Zimmerman and Van Tyne (1957), Canadian Maritimes south to central Florida and whereas Payne (1983) considered it an west to around the 100th meridian from east uncommon transient and summer resident. Texas to eastern North Dakota, and extending Ruby-throated Hummingbirds have been westward across southern Manitoba, recorded arriving as early as the first week in Saskatchewan, and Alberta. They winter from April (Reinoehl 2003), though males generally southern Mexico through Central America to arrive in the first few days of May, followed by extreme northern Panama with many females a few days later. In the UP, spring undertaking nonstop migratory flights across the migration can extend into early June (Binford Gulf of Mexico (Robinson et al. -

Hummingbird, Black-Chinned

Hummingbirds — Family Trochilidae 305 Black-chinned Hummingbird but its special relationship to a plant is not for food Archilochus alexandri but for nesting material. Fuzz from the leaves of the Unlike Costa’s and Anna’s Hummingbirds, the western sycamore is typically the basis of the Black- Black-chinned has a rather conventional biology, chinned Hummingbird’s nest, and the abundance occurring in San Diego County as a fairly common of the hummingbird seems to parallel that of the migrant and summer resident, in the latter role sycamore. mainly in riparian and oak woodland. Like other Breeding distribution: The Black-chinned Hummingbird hummingbirds the Black-chinned feeds on nectar, is fairly widespread over San Diego County’s coastal slope 306 Hummingbirds — Family Trochilidae but strongly concentrated in the county’s northwest cor- ner. In this region it can be quite common, with daily counts as high as 33 along the Santa Margarita River north of Fallbrook (C8) 24 May 2001 (K. L. Weaver). Weaver’s breeding-bird censuses of an 11.7-hectare plot of riparian woodland in this area revealed four to nine females each year from 1989 to 1994 (average 0.5 per hectare). In coast live oak woodland the density is even higher; a census of this habitat in the Santa Margarita Ecological Reserve (C9) in 1989 yielded 1.8 per hect- are (Weaver 1990). Farther south and east the species becomes more localized to the larger riparian strips in the coastal lowland and groves of oak woodland in the foothills. Few Black-chinned Hummingbirds occur above Photo by Anthony Mercieca 3500 feet elevation, and the species is largely if not com- pletely absent as a breeding bird from the Campo Plateau east of Pine Valley and Campo. -

Birds of Indiana

Birds of Indiana This list of Indiana's bird species was compiled by the state's Ornithologist based on accepted taxonomic standards and other relevant data. It is periodically reviewed and updated. References used for scientific names are included at the bottom of this list. ORDER FAMILY GENUS SPECIES COMMON NAME STATUS* Anseriformes Anatidae Dendrocygna autumnalis Black-bellied Whistling-Duck Waterfowl: Swans, Geese, and Ducks Dendrocygna bicolor Fulvous Whistling-Duck Anser albifrons Greater White-fronted Goose Anser caerulescens Snow Goose Anser rossii Ross's Goose Branta bernicla Brant Branta leucopsis Barnacle Goose Branta hutchinsii Cackling Goose Branta canadensis Canada Goose Cygnus olor Mute Swan X Cygnus buccinator Trumpeter Swan SE Cygnus columbianus Tundra Swan Aix sponsa Wood Duck Spatula discors Blue-winged Teal Spatula cyanoptera Cinnamon Teal Spatula clypeata Northern Shoveler Mareca strepera Gadwall Mareca penelope Eurasian Wigeon Mareca americana American Wigeon Anas platyrhynchos Mallard Anas rubripes American Black Duck Anas fulvigula Mottled Duck Anas acuta Northern Pintail Anas crecca Green-winged Teal Aythya valisineria Canvasback Aythya americana Redhead Aythya collaris Ring-necked Duck Aythya marila Greater Scaup Aythya affinis Lesser Scaup Somateria spectabilis King Eider Histrionicus histrionicus Harlequin Duck Melanitta perspicillata Surf Scoter Melanitta deglandi White-winged Scoter ORDER FAMILY GENUS SPECIES COMMON NAME STATUS* Melanitta americana Black Scoter Clangula hyemalis Long-tailed Duck Bucephala -

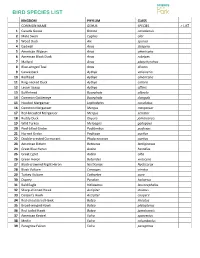

Bird Species List

SCIENCE in the BIRD SPECIES LIST KINGDOM PHYLUM CLASS COMMON NAME GENUS SPECIES ✓ LIST 1 Canada Goose Branta canadensis 2 Mute Swan Cygnus olor 3 Wood Duck Aix sponsa 4 Gadwall Anas strepera 5 American Wigeon Anas americana 6 American Black Duck Anas rubripes 7 Mallard Anas platyrhynchos 8 Blue-winged Teal Anas discors 9 Canvasback Aythya valisineria 10 Redhead Aythya americana 11 Ring-necked Duck Aythya collaris 12 Lesser Scaup Aythya affinis 13 Bufflehead Bucephala albeola 14 Common Goldeneye Bucephala clangula 15 Hooded Merganser Lophodytes cucullatus 16 Common Merganser Mergus merganser 17 Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator 18 Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis 19 Wild Turkey Meleagris gallopavo 20 Pied-billed Grebe Podilymbus podiceps 21 Horned Grebe Podiceps auritus 22 Double-crested Cormorant Phalacrocorax auritus 23 American Bittern Botaurus lentiginosus 24 Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias 25 Great Egret Ardea alba 26 Green Heron Butorides virescens 27 Black-crowned Night Heron Nycticorax Nycticorax 28 Black Vulture Coragyps atratus 29 Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura 30 Osprey Pandion haliaetus 31 Bald Eagle Haliaeetus leucocephalus 32 Sharp-shinned Hawk Accipiter striatus 33 Cooper's Hawk Accipiter cooperii 34 Red-shouldered Hawk Buteo lineatus 35 Broad-winged Hawk Buteo platypterus 36 Red-tailed Hawk Buteo jamaicensis 37 American Kestrel Falco sparverius 38 Merlin Falco columbarius 39 Peregrine Falcon Falco peregrinus SCIENCE in the BIRD SPECIES LIST 40 American Coot Fulica americana 41 COMMON NAME GENUS SPECIES ✓ LIST 42 Killdeer -

Species Risk Assessment

Ecological Sustainability Analysis of the Kaibab National Forest: Species Diversity Report Ver. 1.2 Prepared by: Mikele Painter and Valerie Stein Foster Kaibab National Forest For: Kaibab National Forest Plan Revision Analysis 22 December 2008 SpeciesDiversity-Report-ver-1.2.doc 22 December 2008 Table of Contents Table of Contents............................................................................................................................. i Introduction..................................................................................................................................... 1 PART I: Species Diversity.............................................................................................................. 1 Species List ................................................................................................................................. 1 Criteria .................................................................................................................................... 2 Assessment Sources................................................................................................................ 3 Screening Results.................................................................................................................... 4 Habitat Associations and Initial Species Groups........................................................................ 8 Species associated with ecosystem diversity characteristics of terrestrial vegetation or aquatic systems ...................................................................................................................... -

Appendix A-C: Glossary of Terms

Appendix A Glossary of Terms Appendix A: Glossary of Terms 1. Acronyms and Abbreviations AAR Acquisition Ascertainment Report ACHP Advisory Council on Historic Preservation ACOE United States Army Corps of Engineers ADA Americans with Disabilities Act ADT average daily traffic volumes AHPA Archaeological and Historic Preservation Act Airport Authority San Diego County Regional Airport Authority APCD San Diego Air Pollution Control District APE Area of Potential Effect ARB California Air Resources Board ARPA Archaeological Resources Protection Act BCR Bird Conservation Regions BMPs Best Management Practices BOD biological oxygen demand Caltrans California Department of Transportation CAP Contaminant Assessment Process CAAQS California Ambient Air Quality Standards CCP Comprehensive Conservation Plan CDFG California Department of Fish and Game CEQA California Environmental Quality Act CESA California Endangered Species Act CFR Code of Federal Regulations cfs cubic feet per second cm centimeter CNEL Community Noise Equivalent Level CO Carbon monoxide Code California Fish and Game Code combined federal project Sweetwater River Flood Control Channel/State Highway Route 54/Interstate 5 Project Commission California State Historic Resources Commission Complex San Diego National Wildlife Refuge Complex County County of San Diego CRMP Cultural Resources Management Program dB decibel dBA A-weighted” noise scale dB Leq noise levels presented as average noise levels over a period of minutes or hours DDT Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane DEA Draft environmental -

(Revised with Costs), Petrified Forest National Park

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Natural Resource Condition Assessment Petrified Forest National Park (Revised with Costs) Natural Resource Report NPS/PEFO/NRR—2020/2186 The production of this document cost $ 112,132, including costs associated with data collection, processing, analysis, and subsequent authoring, editing, and publication. ON THE COVER Milky Way over Battleship Rock, Petrified Forest National Park Jacob Holgerson, NPS Natural Resource Condition Assessment Petrified Forest National Park (Revised with Costs) Natural Resource Report NPS/PEFO/NRR—2020/2186 J. Judson Wynne1 1 Department of Biological Sciences Merriam-Powell Center for Environmental Research Northern Arizona University Box 5640 Flagstaff, AZ 86011 November 2020 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. The series supports the advancement of science, informed decision-making, and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series also provides a forum for presenting more lengthy results that may not be accepted by publications with page limitations. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner.