Chapter 5: Physiological Uses of the Squid with Special Emphasis on The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clam Dissection Guideline

Clam Dissection Guideline BACKGROUND: Clams are bivalves, meaning that they have shells consisting of two halves, or valves. The valves are joined at the top, and the adductor muscles on each side hold the shell closed. If the adductor muscles are relaxed, the shell is pulled open by ligaments located on each side of the umbo. The clam's foot is used to dig down into the sand, and a pair of long incurrent and excurrent siphons that extrude from the clam's mantle out the side of the shell reach up to the water above (only the exit points for the siphons are shown). Clams are filter feeders. Water and food particles are drawn in through one siphon to the gills where tiny, hair-like cilia move the water, and the food is caught in mucus on the gills. From there, the food-mucus mixture is transported along a groove to the palps (mouth flaps) which push it into the clam's mouth. The second siphon carries away the water. The gills also draw oxygen from the water flow. The mantle, a thin membrane surrounding the body of the clam, secretes the shell. The oldest part of the clam shell is the umbo, and it is from the hinge area that the clam extends as it grows. I. Purpose: The purpose of this lab is to identify the internal and external structures of a mollusk by dissecting a clam. II. Materials: 2 pairs of safety goggles 1 paper towel 2 pairs of gloves 1 pair of scissors 1 preserved clam 2 pairs of forceps 1 dissecting tray 2 probes III. -

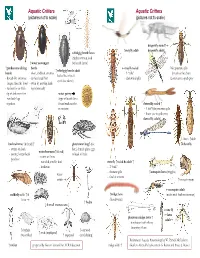

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (Pictures Not to Scale) (Pictures Not to Scale)

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (pictures not to scale) (pictures not to scale) dragonfly naiad↑ ↑ mayfly adult dragonfly adult↓ whirligig beetle larva (fairly common look ↑ water scavenger for beetle larvae) ↑ predaceous diving beetle mayfly naiad No apparent gills ↑ whirligig beetle adult beetle - short, clubbed antenna - 3 “tails” (breathes thru butt) - looks like it has 4 - thread-like antennae - surface head first - abdominal gills Lower jaw to grab prey eyes! (see above) longer than the head - swim by moving hind - surface for air with legs alternately tip of abdomen first water penny -row bklback legs (fbll(type of beetle larva together found under rocks damselfly naiad ↑ in streams - 3 leaf’-like posterior gills - lower jaw to grab prey damselfly adult↓ ←larva ↑adult backswimmer (& head) ↑ giant water bug↑ (toe dobsonfly - swims on back biter) female glues eggs water boatman↑(&head) - pointy, longer beak to back of male - swims on front -predator - rounded, smaller beak stonefly ↑naiad & adult ↑ -herbivore - 2 “tails” - thoracic gills ↑mosquito larva (wiggler) water - find in streams strider ↑mosquito pupa mosquito adult caddisfly adult ↑ & ↑midge larva (males with feather antennae) larva (bloodworm) ↑ hydra ↓ 4 small crustaceans ↓ crane fly ←larva phantom midge larva ↑ adult→ - translucent with silvery bflbuoyancy floats ↑ daphnia ↑ ostracod ↑ scud (amphipod) (water flea) ↑ copepod (seed shrimp) References: Aquatic Entomology by W. Patrick McCafferty ↑ rotifer prepared by Gwen Heistand for ACR Education midge adult ↑ Guide to Microlife by Kenneth G. Rainis and Bruce J. Russel 28 How do Aquatic Critters Get Their Air? Creeks are a lotic (flowing) systems as opposed to lentic (standing, i.e, pond) system. Look for … BREATHING IN AN AQUATIC ENVIRONMENT 1. -

Animal Phylum Poster Porifera

Phylum PORIFERA CNIDARIA PLATYHELMINTHES ANNELIDA MOLLUSCA ECHINODERMATA ARTHROPODA CHORDATA Hexactinellida -- glass (siliceous) Anthozoa -- corals and sea Turbellaria -- free-living or symbiotic Polychaetes -- segmented Gastopods -- snails and slugs Asteroidea -- starfish Trilobitomorpha -- tribolites (extinct) Urochordata -- tunicates Groups sponges anemones flatworms (Dugusia) bristleworms Bivalves -- clams, scallops, mussels Echinoidea -- sea urchins, sand Chelicerata Cephalochordata -- lancelets (organisms studied in detail in Demospongia -- spongin or Hydrazoa -- hydras, some corals Trematoda -- flukes (parasitic) Oligochaetes -- earthworms (Lumbricus) Cephalopods -- squid, octopus, dollars Arachnida -- spiders, scorpions Mixini -- hagfish siliceous sponges Xiphosura -- horseshoe crabs Bio1AL are underlined) Cubozoa -- box jellyfish, sea wasps Cestoda -- tapeworms (parasitic) Hirudinea -- leeches nautilus Holothuroidea -- sea cucumbers Petromyzontida -- lamprey Mandibulata Calcarea -- calcareous sponges Scyphozoa -- jellyfish, sea nettles Monogenea -- parasitic flatworms Polyplacophora -- chitons Ophiuroidea -- brittle stars Chondrichtyes -- sharks, skates Crustacea -- crustaceans (shrimp, crayfish Scleropongiae -- coralline or Crinoidea -- sea lily, feather stars Actinipterygia -- ray-finned fish tropical reef sponges Hexapoda -- insects (cockroach, fruit fly) Sarcopterygia -- lobed-finned fish Myriapoda Amphibia (frog, newt) Chilopoda -- centipedes Diplopoda -- millipedes Reptilia (snake, turtle) Aves (chicken, hummingbird) Mammalia -

Flip Your Lid for Squid!

FLIP YOUR LID FOR SQUID! Adapted from http://njseagrant.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/squid_dissection.pdf PURPOSE Students learn the basics of squid anatomy and physiology by conducting a squid dissection. MATERIALS • frozen whole squid—not “clean” and not cut (get whole squid in frozen section of the grocery store) • hand lenses • dissection pan (plate) • scissors • tweezers • probe or toothpick • paper towels PROCEDURE Dissection of External Anatomy • Have students observe their squids for a few moments looking at the relationship between head and the rest of the body. Then ask students why they think squid are in the family of cephalopods (head-foots). • Tentacles and Arms: Have students count the number of arms. They may use the toothpicks to spread out the squid arms. Ask if all the arms look the same? There should be eight short arms and 2 long arms. Explain that the long thin arms with suckers only at the ends are called tentacles. The tentacles large ends with suckers are known as clubs. The tentacles are used to strike out and capture prey. The eight arms are used to hold onto prey when captured and bring food into its mouth. • Suction Cups: Student may use the magnifying lenses to get a closer look at the suction cups on each arm and tentacles. The suction cups have a small-toothed ring around each one and they are on short stalks. The suction cups are like suckers that help the arms hold onto the prey when it is captured and tries to escape. • Beak and Buccal Mass: Located within the circle of arms students can locate the squids mouth which is a beak. -

Missouri's Freshwater Mussels

Missouri mussel invaders Two exotic freshwater mussels, the Asian clam (Corbicula and can reproduce at a much faster rate than native mussels. MISSOURI’S fluminea) and the zebra mussel (Dreissena polymorpha), have Zebra mussels attach to any solid surface, including industrial found their way to Missouri. The Asian clam was introduced pipes, native mussels and snails and other zebra mussels. They into the western U.S. from Asia in the 1930s and quickly spread form dense clumps that suffocate and kill native mussels by eastward. Since 1968 it has spread rapidly throughout Missouri restricting feeding, breathing and other life functions. Freshwater and is most abundant in streams south of the Missouri River. In You can help stop the spread of these mussels by not moving the mid-1980s, zebra mussels hitched a ride in the ballast waters bait or boat well water from one stream to another; dump and of freighter ships traveling from Asia to the Great Lakes. They drain on the ground before leaving. Check all surfaces of your have rapidly moved into the Mississippi River basin and boat and trailer for zebra mussels and destroy them, along with westward to Oklahoma. vegetation caught on the boat or trailer. Wash with hot (104˚F) Asian clam and zebra mussel larvae have an advantage here water at a carwash and allow all surfaces to dry in the sun for at because they don’t require a fish host to reach a juvenile stage least five days before boating again. MusselsMusselsSue Bruenderman, Janet Sternburg and Chris Barnhart Zebra mussels attached to a native mussel JIM RATHERT ZEBRA CHRIS BARNHART ASIAN CLAM MUSSEL Shells are very common statewide in rivers, ponds and reservoirs A female can produce more than a million larvae at one time, and are often found on banks and gravel bars. -

Squid Giant Axon (Glia/Neurons/Secretion)

Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 71, No. 4, pp. 1188-1192, April 1974 Transfer of Newly Synthesized Proteins from Schwann Cells to the Squid Giant Axon (glia/neurons/secretion) R. J. LASEK*, H. GAINERt, AND R. J. PRZYBYLSKI* Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, Massachusetts 02543 Communicated by Walle J. H. Nauta, November 28, 1973 ABSTRACT The squid giant axon is presented as a teins synthesized in the Schwann cells surrounding the axon model for the study of macromolecular interaction be- tween cells in the nervous system. When the isolated giant are subsequently transferred into the axoplasm. axon was incubated in sea water containing [3Hjleucine MATERIALS AND METHODS for 0.5-5 hr, newly synthesized proteins appeared in the sheath and axoplasm as demonstrated by: (i) radioautogra- Protein synthesis was studied in squid giant axons obtained phy, (ii) separation of the -sheath and axoplasm by extru- from live squid which were kept in a sea tank and used within sion, and (iii) perfusion of electrically excitable axons. hr of obtained The absence of ribosomal RNA in the axoplasm [Lasek, 48 capture. The giant axons were by decapitat- R. J. et al. (1973) Nature 244, 162-165] coupled with other ing the squid and dissecting the axons under a stream of run- evidence indicates that the labeled proteins that are found ning sea water. The axons, 4-6 cm long, were tied with thread in the axoplasm originate in the Schwann cells surrounding at both ends, removed from the mantle, and cleaned of ad- the axon. Approximately 50%70 of the newly synthesized hering connective tissue in a petri dish filled with sea water Schwann cell proteins are transferred to the giant axon. -

Effects of Temperature on Escape Jetting in the Squid Loligo Opalescens

The Journal of Experimental Biology 203, 547–557 (2000) 547 Printed in Great Britain © The Company of Biologists Limited 2000 JEB2451 EFFECTS OF TEMPERATURE ON ESCAPE JETTING IN THE SQUID LOLIGO OPALESCENS H. NEUMEISTER*,§, B. RIPLEY*, T. PREUSS§ AND W. F. GILLY‡ Hopkins Marine Station of Stanford University, Department of Biological Science, 120 Ocean View Boulevard, Pacific Grove, 93950 CA, USA *Authors have contributed equally ‡Author for correspondence (e-mail: [email protected]) §Present address: Department of Neuroscience, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY 10461, USA Accepted 19 November 1999; published on WWW 17 January 2000 Summary In Loligo opalescens, a sudden visual stimulus (flash) giant and non-giant motor axons in isolated nerve–muscle elicits a stereotyped, short-latency escape response that is preparations failed to show the effects seen in vivo, i.e. controlled primarily by the giant axon system at 15 °C. We increased peak force and increased neural activity at low used this startle response as an assay to examine the effects temperature. Taken together, these results suggest that of acute temperature changes down to 6 °C on behavioral L. opalescens is able to compensate escape jetting and physiological aspects of escape jetting. In free- performance for the effects of acute temperature reduction. swimming squid, latency, distance traveled and peak A major portion of this compensation appears to occur in velocity for single escape jets all increased as temperature the central nervous system and involves alterations in the decreased. In restrained squid, intra-mantle pressure recruitment pattern of both the giant and non-giant axon transients during escape jets increased in latency, duration systems. -

Deep-Water Buccinidae (Gastropoda: Neogastropoda) from Sunken Wood, Vents and Seeps: Molecular Phylogeny and Taxonomy Yu.I

Deep-water Buccinidae (Gastropoda: Neogastropoda) from sunken wood, vents and seeps: molecular phylogeny and taxonomy Yu.I. Kantor, N. Puillandre, K. Fraussen, A.E. Fedosov, P. Bouchet To cite this version: Yu.I. Kantor, N. Puillandre, K. Fraussen, A.E. Fedosov, P. Bouchet. Deep-water Buccinidae (Gas- tropoda: Neogastropoda) from sunken wood, vents and seeps: molecular phylogeny and taxonomy. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the UK, Cambridge University Press (CUP), 2013, 93 (8), pp.2177-2195. 10.1017/S0025315413000672. hal-02458197 HAL Id: hal-02458197 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02458197 Submitted on 28 Jan 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Deep-water Buccinidae (Gastropoda: Neogastropoda) from sunken wood, vents and seeps: Molecular phylogeny and taxonomy KANTOR YU.I.1, PUILLANDRE N.2, FRAUSSEN K.3, FEDOSOV A.E.1, BOUCHET P.2 1 A.N. Severtzov Institute of Ecology and Evolution of Russian Academy of Sciences, Leninski Prosp. 33, Moscow 119071, Russia, 2 Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Departement Systematique et Evolution, UMR 7138, 43, Rue Cuvier, 75231 Paris, France, 3 Leuvensestraat 25, B–3200 Aarschot, Belgium ABSTRACT Buccinidae - like other canivorous and predatory molluscs - are generally considered to be occasional visitors or rare colonizers in deep-sea biogenic habitats. -

2,3-Bisphosphoglycerate (2,3-BPG)

11-cis retinal 5.4.2 achondroplasia 19.1.21 active transport, salt 3.4.19 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate 11.2.2 acid-base balance 18.3.34 activity cycle, flies 2.2.2 2,4-D herbicide 3.3.22, d1.4.23 acid coagulation cheese 15.4.36 activity rhythms, locomotor 7.4.2 2,6-D herbicide, mode of action acid growth hypothesis, plant cells actogram 7.4.2 3.2.22 3.3.22 acute mountain sickness 8.4.19 2-3 diphosphoglycerate, 2-3-DPG, acid hydrolases 15.2.36 acute neuritis 13.5.32 in RBCs 3.2.25 acid in gut 5.1.2 acute pancreatitis 9.3.24 2C fragments, selective weedkillers acid rain 13.2.10, 10.3.25, 4.2.27 acyltransferases 11.5.39 d1.4.23 1.1.15 Adams, Mikhail 12.3.39 3' end 4.3.23 acid rain and NO 14.4.18 adaptation 19.2.26, 7.2.31 3D formula of glucose d16.2.15 acid rain, effects on plants 1.1.15 adaptation, chemosensory, 3-D imaging 4.5.20 acid rain, mobilization of soil in bacteria 1.1.27 3-D models, molecular 5.3.7 aluminium 3.4.27 adaptation, frog reproduction 3-D reconstruction of cells 18.1.16 acid rain: formation 13.2.10 17.2.17 3-D shape of molecules 7.2.19 acid 1.4.16 adaptations: cereals 3.3.30 3-D shapes of proteins 6.1.31 acid-alcohol-fast bacteria 14.1.30 adaptations: sperm 10.5.2 3-phosphoglycerate 5.4.30 acidification of freshwater 1.1.15 adaptive immune response 5' end 4.3.23 acidification 3.4.27 19.4.14, 18.1.2 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) 12.1.28, acidification, Al and fish deaths adaptive immunity 19.4.34, 5.1.35 3.4.27 d16.3.31, 5.5.15 6-aminopenicillanic acid 12.1.36 acidification, Al and loss of adaptive radiation 8.5.7 7-spot ladybird -

Structure and Function of the Digestive System in Molluscs

Cell and Tissue Research (2019) 377:475–503 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-019-03085-9 REVIEW Structure and function of the digestive system in molluscs Alexandre Lobo-da-Cunha1,2 Received: 21 February 2019 /Accepted: 26 July 2019 /Published online: 2 September 2019 # Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract The phylum Mollusca is one of the largest and more diversified among metazoan phyla, comprising many thousand species living in ocean, freshwater and terrestrial ecosystems. Mollusc-feeding biology is highly diverse, including omnivorous grazers, herbivores, carnivorous scavengers and predators, and even some parasitic species. Consequently, their digestive system presents many adaptive variations. The digestive tract starting in the mouth consists of the buccal cavity, oesophagus, stomach and intestine ending in the anus. Several types of glands are associated, namely, oral and salivary glands, oesophageal glands, digestive gland and, in some cases, anal glands. The digestive gland is the largest and more important for digestion and nutrient absorption. The digestive system of each of the eight extant molluscan classes is reviewed, highlighting the most recent data available on histological, ultrastructural and functional aspects of tissues and cells involved in nutrient absorption, intracellular and extracellular digestion, with emphasis on glandular tissues. Keywords Digestive tract . Digestive gland . Salivary glands . Mollusca . Ultrastructure Introduction and visceral mass. The visceral mass is dorsally covered by the mantle tissues that frequently extend outwards to create a The phylum Mollusca is considered the second largest among flap around the body forming a space in between known as metazoans, surpassed only by the arthropods in a number of pallial or mantle cavity. -

Effect of Fmrfamide on Voltage-Dependent Currents In

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.29.318691; this version posted October 1, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. A. Chrachri 1 Effect of FMRFamide on voltage-dependent currents in identified centrifugal 2 neurons of the optic lobe of the cuttlefish, Sepia officinalis 3 4 Abdesslam Chrachri 5 University of Plymouth, Dept of Biological Sciences, Drake Circus, Plymouth, PL4 6 8AA, UK and the Marine Biological Association of the UK, Citadel Hill, Plymouth 7 PL1 2PB, UK 8 Phone: 07931150796 9 Email: [email protected] 10 11 Running title: Membrane currents in centrifugal neurons 12 13 Key words: cephalopod, voltage-clamp, potassium current, calcium currents, sodium 14 current, FMRFamide. 15 16 Summary: FMRFamide modulate the ionic currents in identified centrifugal neurons 17 in the optic lobe of cuttlefish: thus, FMRFamide could play a key role in visual 18 processing of these animals. 19 - 1 - bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.29.318691; this version posted October 1, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. A. Chrachri 20 Abstract 21 Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings from identified centrifugal neurons of the optic 22 lobe in a slice preparation allowed the characterization of five voltage-dependent 23 currents; two outward and three inward currents. The outward currents were; the 4- 24 aminopyridine-sensitive transient potassium or A-current (IA), the TEA-sensitive 25 sustained current or delayed rectifier (IK). -

Lab 5: Phylum Mollusca

Biology 18 Spring, 2008 Lab 5: Phylum Mollusca Objectives: Understand the taxonomic relationships and major features of mollusks Learn the external and internal anatomy of the clam and squid Understand the major advantages and limitations of the exoskeletons of mollusks in relation to the hydrostatic skeletons of worms and the endoskeletons of vertebrates, which you will examine later in the semester Textbook Reading: pp. 700-702, 1016, 1020 & 1021 (Figure 47.22), 943-944, 978-979, 1046 Introduction The phylum Mollusca consists of over 100,000 marine, freshwater, and terrestrial species. Most are familiar to you as food sources: oysters, clams, scallops, and yes, snails, squid and octopods. Some also serve as intermediate hosts for parasitic trematodes, and others (e.g., snails) can be major agricultural pests. Mollusks have many features in common with annelids and arthropods, such as bilateral symmetry, triploblasty, ventral nerve cords, and a coelom. Unlike annelids, mollusks (with one major exception) do not possess a closed circulatory system, but rather have an open circulatory system consisting of a heart and a few vessels that pump blood into coelomic cavities and sinuses (collectively termed the hemocoel). Other distinguishing features of mollusks are: z A large, muscular foot variously modified for locomotion, digging, attachment, and prey capture. z A mantle, a highly modified epidermis that covers and protects the soft body. In most species, the mantle also secretes a shell of calcium carbonate. z A visceral mass housing the internal organs. z A mantle cavity, the space between the mantle and viscera. Gills, when present, are suspended within this cavity.