Ed 354 749 Author Title Institution Report No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RM New Entries 2016 Mar.Pdf

International Plant Nutrition Institute Regional Office • Southeast Asia Date: March 31, 2016 Page: 1 of 88 New Entries to IPNI Library as References Roberts T. L. 2008. Improving Nutrient Use Efficiency. Turkish Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, 32:177-182. Reference ID: 21904 Notes: #21904e Abstract: Public interest and awareness of the need for improving nutrient use efficiency is great, but nutrient use efficiency is easily misunderstood. Four indices of nutrient use efficiency are reviewed and an example of different applications of the terminology show that the same data set might be used to calculate a fertilizer N efficiency of 21% or 100%. Fertilizer N recovery efficiencies from researcher managed experiments for major grain crops range from 46% to 65%, compared to on-farm N recovery efficiencies of 20% to 40%. Fertilizer use efficiency can be optimized by fertilizer best management practices that apply nutrients at the right rate, time, and place. The highest nutrient use efficiency always occurs at the lower parts of the yield response curve, where fertilizer inputs are lowest, but effectiveness of fertilizers in increasing crop yields and optimizing farmer profitability should not be sacrificed for the sake of efficiency alone. There must be a balance between optimal nutrient use efficiency and optimal crop productivity. Souza L. F. D.and D. H. Reinhardt. 2015. Pineapple. Pages 179-201 IPO. Reference ID: 21905 Notes: #21905e Abstract: Pineapple is one of the tropical fruits in greatest demand on the international market, with world production in 2004 of 16.1 million mt. Of this total, Asia produces 51% (8.2 million mt), with Thailand (12%) and the Philippines (11%) the two most productive countries. -

Prosperity, Abundance and Superstitions Galore

www.ipohecho.com.my FREE COPY IPOH ECHO IPOH WISHES ALL OUR READERS Your Voiceechoecho In The Community A HAPPY & PROSPEROUS CHINESE NEW YEAR ISSUE 91 February 12-28, 2010 PP 14252/10/2010(025567) POLO GROUND THE NEW GIRL POMELO FARMERS – IS A SOLUTION ON THE BLOCK OF TAMBUN GET POSSIBLE? THEIR LAND – FINALLY GO ONLINE www.ipohecho.com.my Pg 3 Pg 8 Pg 9 FOR THE LATEST NEWS. WE UPDATE REGULARLY PROSPERITY, ABUNDANCE AND SUPERSTITIONS GALORE hinese New Year is the most significant of all the traditional Chinese festivals. It is an auspicious start Cto the year and at this time the Chinese are on their best behaviour. Not to do so may prove catastrophic. There is no room for open hostilities. Every one is gracious and willing to forgive and forget. By embracing a spirit of goodwill and spreading joy and peace they experience moments of blessed calm and sheer bliss. It is a highly commendable way to begin the year. Chinese New Year, falling between 20th January and 20th February of the Gregorian calendar each year, would be mundane and a nonentity without the accompaniment of traditions and age-old taboos and superstitions. They are still practised although many Chinese with modern ideas regard them with scepticism. Nevertheless, Chinese New Year traditions and customs remain robust because they provide continuity. They bridge the divide between past and present and in this way offer the Chinese a sense of identity. continued on page 2 2 IPOH ECHO FEBRUARY 12-28, 2010 Your Voice In The Community TRADITION AND TABOO COMBINE TO USHER IN CHINESE NEW YEAR but no- to the spirit and people re- ity. -

Voices of Malaysian Indian Writers Writing in English

Kajian Malaysia, Vol. 38, No. 2, 2020, 25–59 VOICES OF MALAYSIAN INDIAN WRITERS WRITING IN ENGLISH Shangeetha R.K. English Language Department, Faculty of Languages and Linguistics, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, MALAYSIA Email: [email protected] Published online: 30 October 2020 To cite this article: Shangeetha, R.K. 2020. Voices of Malaysian Indian writers writing in English. Kajian Malaysia 38(2): 25–59. https://doi.org/10.21315/km2020.38.2.2 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.21315/km2020.38.2.2 ABSTRACT This article brings together a compilation of poems, short stories and novels written by Malaysian Indian writers from 1940 to 2018. These verse and prose forms collected here were all written in English within the last 80 years. In fact, in the contemporary Malaysian literary scene, the number of works by Malaysian Indian writers writing in English, has increased compared to the previous volumes which were primarily dominated by writers such as Cecil Rajendra, K.S. Maniam and M. Shanmughalingam. It is interesting to note that the interest of writing poetry and prose among the younger Malaysian Indian writers is on the rise with publications from younger poets and writers such as Paul GnanaSelvam and Cheryl Ann Fernando. In Malaysia, poetry and prose written by Malaysian Indian writers in English is diversifying with many promising new talents. Departing from the Malaysian Indian diaspora, the emerging themes of these lesser-known writers are more liberal. As such, the main aim of this article is to map out the cartography of Malaysian Indian works in these three genres; poem, short story and novel, and identify the main thematic concerns in the writings. -

Mak Nyah Cabaret Dance Performance at Three Nightclubs in Klang Valley

MAK NYAH CABARET DANCE PERFORMANCE AT THREE NIGHTCLUBS IN KLANG VALLEY SARAH LOW MAY POH Malaya of CULTURAL CENTRE UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA KUALA LUMPUR University 201 8 MAK NYAH CABARET DANCE PERFORMANCE AT THREE NIGHTCLUBS IN KLANG VALLEY SARAH LOW MAY POH Malaya DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIRofEMENT S FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTERS IN PERFORMING ARTS (DANCE) CULTURAL CENTRE UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA KUALA LUMPUR University201 8 UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA ORIGINAL LITERARY WORK DECLARATION Name of Candidate: Sarah Low May Poh Matric No: RGK120002 Name of Degree: Masters in Performing Arts (Dance) Title of Dissertation: Mak Nyah Cabaret Dance Performance at Three Clubs in Klang Valley Field of Study: Gender Studies I do solemnly and sincerely declare that: (1) I am the sole author/writer of this Work; (2) This Work is original; (3) Any use of any work in which copyright exists was done by way of fair dealing and for permitted purposes and any excerpt or extract from, or reference to or reproduction of any copyright work has been disclosed expressly and sufficiently and the title of the Work and its authorship have been acknowledged in this Work; (4) I do not have any actual knowledge nor Malayado I ought reasonably to know that the making of this work constitutes an infringement of any copyright work; (5) I hereby assign all and every rights in the copyright to this Work to the University of Malaya (“UM”), who henceforth shall be owner of the copyright in this Work and that anyof reproduction or use in any form or by any means whatsoever is prohibited without the written consent of UM having been first had and obtained; (6) I am fully aware that if in the course of making this Work I have infringed any copyright whether intentionally or otherwise, I may be subject to legal action or any other action as may be determined by UM. -

Language Access Issue (Winter 2016-2017)

Consumer Action Non-Profit Org. 1170 Market Street, Suite 500 U.S. Postage San Francisco, CA 94102 PAID San Francisco, CA CONSUMER Permit # 10402 ACTION Change Service Requested NEWS www.consumer-action.org • Winter 2016-2017 Language Access Report Meeting the needs of Advocates work to tear limited English speakers down language barriers By Monica Steinisch that put their homes at risk of fore- By Ruth Susswein insult to injury, their monthly closure because the borrowers didn’t mortgage payment was about to rise here are approximately 26 understand they might be eligible etting a mortgage is chal- from $1,983 a month to $3,350. It million people in the U.S. for a loan modification. During the lenging enough without turned out that their “friend,” the who speak limited Eng- recent foreclosure crisis, some LEP the language barriers that Spanish-English interpreter for the Tlish—16 million of them speak Gfurther disadvantage borrowers with borrowers paid thousands to scam- mortgage documents, did not act in Spanish as their first language. mers for foreclosure prevention help limited English skills. Most borrow- the couple’s best interest. While language barriers may not ers blanch when faced with a variety that never materialized. Unfortunately many homeown- always hinder limited English profi- of loan offerings and reams of clos- Consumer Action, as part of the ers have to rely on friends, family, cient (LEP) consumers as they carry ing paperwork, but consumers with coalition Americans for Financial sometimes even children to inter- out the routine tasks of daily life, limited English proficiency (LEP) Reform (AFR), has called on the pret important documents when a lack of English fluency can make may be more easily led into traps by Consumer Financial Protection dealing with lenders and servicers. -

W GLITZ GLAMOUR

BIBLIOASIA JAN – MAR 2017 Vol. 12 / Issue 04 / Feature Dancers by Night, Benefactors by Day wasn’t just the “Queen of Striptease” who school Happy Charity School, in an obvious titillated men on stage; she was equally nod to the most popular landmark in Geylang People whom I spoke to about the cabaret generous in donating to various charities then – the Happy World amusement park.4 life would mention how the “lancing girls” that cared for children, old folks, tuber- The first principal of the school was were the main draw for the men. For as little culosis patients and the blind. Wong Guo Liang, a well-known calligrapher. as a dollar for a set of three dance coupons, Rose Chan wasn't the only “charity When Wong first met Madam He at the male customers could take the girl of their queen” from the cabaret world. There were interview for the position, he remembered choice for a spin on the dance floor. But, two other women from the Happy World being struck by her charisma and generos- invariably, the discussion would turn to the cabaret who worked tirelessly to start a free ity. Despite the irony of her situation, she most famous “lancing” girl of all time: Rose school for children. These women became advised him to set a good example as the Chan, a former beauty queen and striptease the founders of the Happy School in Geylang. principal and live up to the responsibility of dancer who joined Happy World Cabaret in being a role model for his charges. -

Front Cover Inside Front Cover Inside Back Cover

Back Cover Front Cover Inside Front Cover Inside Back Cover Cover photo credits: Chinatown, 1920, Lim Choo Sye Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore Gotong royong procession, Mrs. J. A. Bennett Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore. Remittance letter by Liu Shi Zhao, Ref no 040002230, courtesy of the Koh Seow Chuan collection, National Library, Singapore. Chinese family in postwar Singapore, Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore Interest groups meeting the BMA, David Ng Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore. Nanyang University, Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore. acsep: knowledge for good i ACSEP The Asia Centre for Social Entrepreneurship and Philanthropy (ACSEP) is an academic research centre at the National University of Singapore (NUS) Business School, staffed by an international multidisciplinary research team. Formally established in April 2011, the Centre has embraced a geographic focus spanning 34 nations and special administrative regions across Asia. ACSEP aims to advance understanding and the impactful practice of social entrepreneurship and philanthropy in Asia through research and education. Its working papers are authored by academia and in-house researchers, who provide thought leadership and offer insights into key issues and concerns confronting socially driven organisations. Asia Centre for Social Entrepreneurship & Philanthropy (ACSEP), NUS Business School BIZ2 Building, #05-13 1 Business Link, Singapore 117592 Tel : +65 6516 5277 E-mail : [email protected] https://bschool.nus.edu.sg/acsep ii About the Author Yu-lin Ooi Yu-lin Ooi is Senior Research Consultant with the Asia Centre for Social Entrepreneurship and Philanthropy (ACSEP), documenting the journey of philanthropy in Singapore’s social history. -

The Spectral Nanyang: Recollection, Nation, and the Genealogy of Chineseness

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 The Spectral Nanyang: Recollection, Nation, And The Genealogy Of Chineseness Zhou Hau Liew University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Liew, Zhou Hau, "The Spectral Nanyang: Recollection, Nation, And The Genealogy Of Chineseness" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3054. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3054 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3054 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Spectral Nanyang: Recollection, Nation, And The Genealogy Of Chineseness Abstract Decolonizing counter-narratives to Malaysia's official national history are insufficiento t account for the complex legacies of nationalism in Malaysia, and its relationship with Chineseness, race, and colonialism. This dissertation close reads the fictional works of three contemporary Mahua (Malaysian Chinese) authors – Zhang Guixing, Ng Kim Chew and Li Tianbao – to argue that Mahua identity is haunted by a nationalistic Chineseness deriving from late 19th and early 20th century mainland China, which defines itself on the basis of an archaic, civilizational imaginary, with undertones of racial and cultural purity. This conditions Mahua political and cultural identity during flashpoints of Malaysian history across Malaya (now Peninsular Malaysia) and Borneo (now partially East Malaysia), spanning anti-colonial Hua- dominated communist movements during the Cold War, such as the Sarawak Communist Insurgency (1962-1990) and the Malayan Communist Party during the Malayan Emergencies (1948-1960 and 1968-1989); and Hua literati responses to a post-1969 renewal of the politics of Malay indigeneity. -

Mak Nyah Cabaret Dance Performance at Three Nightclubs in Klang Valley

MAK NYAH CABARET DANCE PERFORMANCE AT THREE NIGHTCLUBS IN KLANG VALLEY SARAH LOW MAY POH CULTURAL CENTRE UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA KUALA LUMPUR 2018 MAK NYAH CABARET DANCE PERFORMANCE AT THREE NIGHTCLUBS IN KLANG VALLEY SARAH LOW MAY POH DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTERS IN PERFORMING ARTS (DANCE) CULTURAL CENTRE UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA KUALA LUMPUR 2018 UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA ORIGINAL LITERARY WORK DECLARATION Name of Candidate: Sarah Low May Poh (I.C No: 880219565662) Matric No: RGK120002 Name of Degree: Masters in Performing Arts (Dance) Title of Dissertation: Mak Nyah Cabaret Dance Performance at Three Clubs in Klang Valley Field of Study: Gender Studies I do solemnly and sincerely declare that: (1) I am the sole author/writer of this Work; (2) This Work is original; (3) Any use of any work in which copyright exists was done by way of fair dealing and for permitted purposes and any excerpt or extract from, or reference to or reproduction of any copyright work has been disclosed expressly and sufficiently and the title of the Work and its authorship have been acknowledged in this Work; (4) I do not have any actual knowledge nor do I ought reasonably to know that the making of this work constitutes an infringement of any copyright work; (5) I hereby assign all and every rights in the copyright to this Work to the University of Malaya (“UM”), who henceforth shall be owner of the copyright in this Work and that any reproduction or use in any form or by any means whatsoever is prohibited without the written consent of UM having been first had and obtained; (6) I am fully aware that if in the course of making this Work I have infringed any copyright whether intentionally or otherwise, I may be subject to legal action or any other action as may be determined by UM. -

Download

BIBLIOGRAPHY 561 Bibliography Parliamentary Material Singapore Legislative Assembly Debates 1955–1962. Singapore Parliamentary Debates Official Reports, 1965. Commission of Inquiry into the $500,000 bank account of Mr. Chew Swee Kee and the Income Tax Dept. Leakage in Connection Therewith (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1959). Debates of the United Kingdom Legislative Assembly, 17 Jun 1958 at col 878. Great Britain, Colonial Office, Record of Baling Talks in December 1955, CO 1030/29. Interim Report of the Malayanization Commission, Dr BR Sreenivasan (Chairman) (Singapore: Government Printer, 1956) Public Services Salaries Commission of Malaya Report (Kuala Lumpur: Government Press, 1947) Report of the Committee for the Reconstitution of the Singapore Legislative Council, 1947. Report of the Constitutional Commission 1966 (Singapore: Government Printer, 1966). Report of the Constitutional Commission, Singapore, 1954. Report of the Select Committee on Languages in Legislative Assembly Debates, LA 20 of 1957 (Singapore: Government Printers, 1957) Report of the Select Committee on the Criminal Procedure Code (Amendment) Bill (Singapore: Government Printer, 1960). Report of the Select Committee on the Criminal Procedure Code (Amendment) Bill, Parl 8 of 1969. Report of the Singapore Constitutional Conference Held in March and April, 1957, Cmnd 147. Singapore Constitutional Conference, Cmd 9777 of 1956. Private Papers The David Marshall Papers, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. 17 Marshall_S'pore Biblio 561 11/21/08, 9:16 AM 562 MARSHALL OF SINGAPORE Newspaper Articles ‘13 Men — All With One Aim’ Singapore Tiger Standard, 17 Mar 1956. ‘28 Years’ Service Ends in Gaol’ The Straits Times, 14 Oct 1949. ‘61 Delegates to Go to Red China’ Singapore Tiger Standard, 11 Jul 1956. -

Persembahan Bogel 'Rose Chan' Dan Bantahan Masyarakat Di Kedah

PERSEMBAHAN BOGEL ‘ROSE CHAN’ DAN BANTAHAN MASYARAKAT DI KEDAH PADA DEKAD AWAL 1960-1970AN. MOHD KASRI SAIDON PUSAT PENGAJIAN PENDIDIKAN DAN BAHASA MODEN UNIVERSITI UTARA MALAYSIA Pengenalan Tajuk sebegini mungkin menjadi satu tanda tanya bagi para pembaca khususnya sejarawan dan peminat sejarah di Malaysia khususnya di Kedah. Tentu sahaja ianya dilihat sebagai satu aktiviti yang tidak berlesen atau dalam erti kata lain ianya haram. Hakikatnya adalah disebaliknya dan memerlukan banyak pemahaman tentang situasi sosial, perundangan yang membawa kepada rintisan cerita kepada tajuk yang dinyatakan di atas. Tajuk ini berkait rapat dengan seorang individu yang bernama Rose Chan yang telah mencipta satu kejutan dan fenomena baru kepada suasana hiburan pada era tahun 1960an khususnya di bandar besar seperti Singapura,Kuala Lumpur dan Pulau Pinang. Hal ini kemudiannya melebar pula ke bandar-bandar kecil di banyak tempat di Tanah Melayu ketika itu. Di Kedah persembahan Rose Chan ini menjadi bualan di Alor Setar, Sungai Petani dan juga pekan kecil yang lain. Tarikan utamanya hanyalah satu iaitu aksi separuh bogel dan persembahan pentas yang begitu kontraversi.Aksi sebegini adalah sesuatu yang baru dan diluar dari kebiasaan atau budaya orang timur khususnya orang Melayu.Malah pada bangsa lain seperti Cina dan India juga ianya bukanlah sesuatu yang lunak untuk diterima. Persembahan yang begitu menjadi bualan ini kemudiannya mencetuskan tentangan oleh beberapa pertubuhan dan juga orang perseorangan di beberapa tempat. Di Kedah ianya ditentang hebat oleh ramai individu yang berpengaruh sama ada dari aliran politik atau pertubuhan bukan kerajaan 1274 (NGO). Tentangan sebegitu pada masa itu memperlihatkan satu bentuk kesefahaman rakyat kepada gejala yang dianggap tidak bermoral ini dari menular ke dalam masyarakat. -

Hansard, I Would Like to Repeat the Views Expressed in My "Letter to Hong Kong" Which Was Broadcast at RTHK Radio III Last Sunday

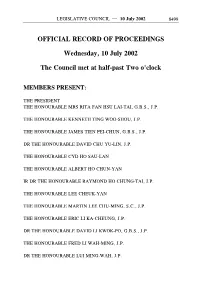

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 10 July 2002 8499 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 10 July 2002 The Council met at half-past Two o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE MRS RITA FAN HSU LAI-TAI, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE KENNETH TING WOO-SHOU, J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TIEN PEI-CHUN, G.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID CHU YU-LIN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CYD HO SAU-LAN THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE MARTIN LEE CHU-MING, S.C., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ERIC LI KA-CHEUNG, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LUI MING-WAH, J.P. 8500 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 10 July 2002 THE HONOURABLE NG LEUNG-SING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE MRS SELINA CHOW LIANG SHUK-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE HUI CHEUNG-CHING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KWOK-KEUNG THE HONOURABLE CHAN YUEN-HAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE BERNARD CHAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE SIN CHUNG-KAI THE HONOURABLE ANDREW WONG WANG-FAT, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P.