Women in Rhondda Society, C.1870 - 1939

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Community Profile – Ynyswen, Treorchy and Cwmparc

Community Profile – Ynyswen, Treorchy and Cwmparc Version 5 – will be updated and reviewed next on 29.05.20 Treorchy is a town and electoral ward in the county borough of Rhondda Cynon Taf in the Rhondda Fawr valley. Treorchy is one of the 16 communities that make up the Rhondda. Treorchy is bordered by the villages of Cwmparc and Ynyswen which are included within the profile. The population is 7,694, 4,404 of which are working age. Treorchy has a thriving high street with many shops and cafes and is in the running as one of the 3 Welsh finalists for Highs Street of the Year award. There are 2 large supermarkets and an Treorchy High Street industrial estate providing local employment. There is also a High school with sixth form Cwmparc Community Centre opportunities for young people in the area Cwmparc is a village and district of the community of Treorchy, 0.8 miles from Treorchy. It is more of a residential area, however St Georges Church Hall located in Cwmparc offers a variety of activities for the community, including Yoga, playgroup and history classes. Ynyswen is a village in the community of Treorchy, 0.6 miles north of Treorchy. It consists mostly of housing but has an industrial estate which was once the site of the Burberry’s factory, one shop and the Forest View Medical Centre. Although there are no petrol stations in the Treorchy area, transport is relatively good throughout the valley. However, there is no Sunday bus service in Cwmparc. Treorchy has a large population of young people and although there are opportunities to engage with sport activities it is evident that there are fewer affordable activities for young women to engage in. -

Newsletter 2004

Freemen of Llantrisant GENERAL MEETING 2004 A General Meeting of Freemen of Llantrisant will be held at Llantrisant IN 1346, my friends, th When Edward III, he reigned, Guildhall at 7:30pm on Friday 15 October 2004, to discuss and debate the A charter for Llantrisant folk, works of the Trust over the past year and to accept suggestions to improve Le Dispenser, he proclaimed. its effectiveness. Yes, Hugh, Lord of Glamorgan A vacancy for a Freemen Trustee has arisen and, consequently, an election Enrolled Freemen for trade: must take place. Any Freeman may stand for election, but he will be "You can sell your wares for free," he said, required to attend personally and be nominated and seconded by Freemen "From Fanheulog to Brynteg." present at the meeting. Now England was at war with France, A battle raged at Crecy. LLANTRISANT CASTLE FEASIBILITY STUDY Long bowmen from the town took part, During the year plenty of debate was held to discuss the future of The result for the French was messy. Llantrisant Castle and whether the 13th century ruin could be developed into And when these veterans returned, a major tourist attraction. Rhondda Cynon Taf County Borough Council Upon each one bestowed commissioned Richard Dean of Dean & Cheason Associates to carry out a That Freemanship by way of thanks full feasibility study of the site and offer a number of ideas of how to For being brave and bold. develop the castle into depending on suitable funding being sought. And so to 1889, Llantrisant Trust was founded, To manage all the Freeman's lands, A public exhibition was held in the old town and visitors viewed a number The old order had been grounded. -

Maerdy, Ferndale and Blaenllechau

Community Profile – Maerdy, Ferndale and Blaenllechau Version 6 – will be updated and reviewed next on 29.05.20 Maerdy Miners Memorial to commemorate the mining history in the Rhondda is Ferndale high street. situated alongside the A4233 in Maerdy on the way to Aberdare Ferndale is a small town in the Rhondda Fach valley. Its neighboring villages include Maerdy and Blaenllechau. Ferndale is 2.1 miles from Maerdy. It is situated at the top at the Rhondda Fach valley, 8 miles from Pontypridd and 20 miles from Cardiff. The villages have magnificent scenery. Maerdy was the last deep mine in the Rhondda valley and closed in 1985 but the mine was still used to transport men into the mine for coal to be mined to the surface at Tower Colliery until 1990. The population of the area is 7,255 of this 21% is aged over 65 years of age, 18% are aged under 14 and 61% aged 35-50. Most of the population is of working age. 30% of people aged between 16-74 are in full time employment in Maerdy and Ferndale compared with 36% across Wales. 40% of people have no qualifications in Maerdy & Ferndale compared with 26% across Wales (Census, 2011). There is a variety of community facilities offering a variety of activities for all ages. There are local community buildings that people access for activities. These are the Maerdy hub and the Arts Factory. Both centre’s offer job clubs, Citizen’s Advice Bureau (CAB) and signposting. There is a sports centre offering football, netball rugby, Pen y Cymoedd Community Profile – Maerdy and Ferndale/V6/02.09.2019 basketball, tennis and a gym. -

Aberaman, Godreaman, Cwmaman and Abercwmboi

Community Profile – Aberaman, Godreaman, Cwmaman and Abercwmboi Aberaman is a village near Aberdare in the county borough of Rhondda Cynon Taf. It was heavily dependent on the coal industry and the population, as a result, grew rapidly in the late nineteenth century. Most of the industry has now disappeared and a substantial proportion of the working population travel to work in Cardiff. Within the area of Aberaman lies three smaller villages Godreaman, Cwmaman and Abercwmboi. The border of Aberaman runs down the Cynon River. Cwmaman sandstone for climbing sports Cwmaman is a former coal mining village near Aberdare. The name is Welsh for Aman Valley and the River Aman flows through the village. It lies in the valley of several mountains. Within the village, there are two children's playgrounds and playing fields. At the top of the village there are several reservoirs accessible from several footpaths along the river. Cwmaman Working Men’s club was the first venue the band the Stereophonics played from, the band were all from the area. Cwmaman is the venue for an annual music festival which has been held Abercwmboi RFC a community every year since 2008 on the last weekend of September. venue for functions. Abercwmboi has retained its identity and not been developed as have many other Cynon Valley villages. As a result, is a very close and friendly community. Many families continue to remain within the community and have a great sense of belonging. Abercwmboi RFC offer a venue for community functions and have teams supporting junior rugby, senior rugby and women’s rugby. -

Rhondda Cynon Taf Christmas 2019 & New Year Services 2020

Rhondda Cynon Taf Christmas 2019 & New Year Services 2020 Christmas Christmas Service Days of Sunday Monday Boxing Day Friday Saturday Sunday Monday New Year's Eve New Year's Day Thursday Operators Route Eve Day number Operation 22 / 12 / 19 23 / 12 / 19 26 / 12 / 19 27 / 12 / 19 28 / 12 / 19 29 / 12 / 19 30 / 12 / 19 31 / 12 / 19 01 / 01 / 20 02 / 01 / 20 24 / 12 / 19 25 / 12 / 19 School School School Mon to Sat Saturday Normal Saturday Saturday Stagecoach 1 Aberdare - Abernant No Service Holiday Holiday No Service No Service No Service No Service Holiday (Daytime) Service Service Service Service Service Service Service School School School Mon to Sat Saturday Normal Saturday Saturday Stagecoach 2 Aberdare - Tŷ Fry No Service Holiday Holiday No Service No Service No Service No Service Holiday (Daytime) Service Service Service Service Service Service Service Early Finish Globe Mon to Sat Penrhiwceiber - Cefn Normal Normal Normal Normal Normal Normal 3 No Service No Service No Service No Service (see No Service Coaches (Daytime) Pennar Service Service Service Service Service Service summary) School School School Mon to Sat Aberdare - Llwydcoed - Saturday Normal Saturday Saturday Stagecoach 6 No Service Holiday Holiday No Service No Service No Service No Service Holiday (Daytime) Merthyr Tydfil Service Service Service Service Service Service Service Harris Mon to Sat Normal Normal Saturday Normal Saturday Saturday Normal 7 Pontypridd - Blackwood No Service No Service No Service No Service No Service Coaches (Daytime) Service Service Service -

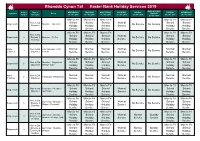

Rhondda Cynon Taf Easter Bank Holiday Services 2019

Rhondda Cynon Taf Easter Bank Holiday Services 2019 BANK HOLIDAY Service Days of WEDNESDAY THURSDAY GOOD FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY Operators Route MONDAY number Operation 17 / 04 / 2019 18 / 04 / 2019 19 / 04 / 2019 20 / 04 / 2019 21 / 04 / 2019 23 / 04 / 2019 24 / 04 / 2019 22 / 04 / 2019 Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Sat School School School Normal School School Stagecoach 1 Aberdare - Abernant No Service No Service (Daytime) Holiday Holiday Holiday Service Holiday Holiday Service Service Service Service Service Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Sat School School School Normal School School Stagecoach 2 (Daytime & Aberdare - Tŷ Fry No Service No Service Evening) Holiday Holiday Holiday Service Holiday Holiday Service Service Service Service Service Globe Mon to Sat Penrhiwceiber - Cefn Normal Normal Normal Normal Normal Normal 3 No Service No Service Coaches (Daytime) Pennar Service Service Service Service Service Service Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Sat Aberdare - Llwydcoed - School School School Normal School School Stagecoach 6 No Service No Service (Daytime) Merthyr Tydfil Holiday Holiday Holiday Service Holiday Holiday Service Service Service Service Service Harris Mon to Sat Normal Normal Normal Normal Normal Normal 7 Pontypridd - Blackwood No Service No Service Coaches (Daytime) Service Service Service Service Service Service Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Fri Mon to Sat Penderyn - Aberdare - School -

Starting School 2018-19 Cover Final.Qxp Layout 1

Starting School 2018-2019 Contents Introduction 2 Information and advice - Contact details..............................................................................................2 Part 1 3 Primary and Secondary Education – General Admission Arrangements A. Choosing a School..........................................................................................................................3 B. Applying for a place ........................................................................................................................4 C.How places are allocated ................................................................................................................5 Part 2 7 Stages of Education Maintained Schools ............................................................................................................................7 Admission Timetable 2018 - 2019 Academic Year ............................................................................14 Admission Policies Voluntary Aided and Controlled (Church) Schools ................................................15 Special Educational Needs ................................................................................................................24 Part 3 26 Appeals Process ..............................................................................................................................26 Part 4 29 Provision of Home to School/College Transport Learner Travel Policy, Information and Arrangements ........................................................................29 -

Warwickshire County Record Office

WARWICKSHIRE COUNTY RECORD OFFICE Priory Park Cape Road Warwick CV34 4JS Tel: (01926) 738959 Email: [email protected] Website: http://heritage.warwickshire.gov.uk/warwickshire-county-record-office Please note we are closed to the public during the first full week of every calendar month to enable staff to catalogue collections. A full list of these collection weeks is available on request and also on our website. The reduction in our core funding means we can no longer produce documents between 12.00 and 14.15 although the searchroom will remain open during this time. There is no need to book an appointment, but entry is by CARN ticket so please bring proof of name, address and signature (e.g. driving licence or a combination of other documents) if you do not already have a ticket. There is a small car park with a dropping off zone and disabled spaces. Please telephone us if you would like to reserve a space or discuss your needs in any detail. Last orders: Documents/Photocopies 30 minutes before closing. Transportation to Australia and Tasmania Transportation to Australia began in 1787 with the sailing of the “First Fleet” of convicts and their arrival at Botany Bay in January 1788. The practice continued in New South Wales until 1840, in Van Dieman’s Land (Tasmania) until 1853 and in Western Australia until 1868. Most of the convicts were tried at the Assizes, The Court of the Assize The Assizes dealt with all cases where the defendant was liable to be sentenced to death (nearly always commuted to transportation for life. -

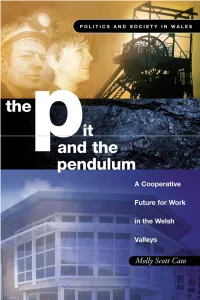

The Pit and the Pendulum: a Cooperative Future for Work in The

Pit and the Pendulum Prelims.qxd 02/03/04 13:34 Page i POLITICS AND SOCIETY IN WALES The Pit and the Pendulum Pit and the Pendulum Prelims.qxd 02/03/04 13:34 Page ii POLITICS AND SOCIETY IN WALES SERIES Series editor: Ralph Fevre Previous volumes in the series: Paul Chaney, Tom Hall and Andrew Pithouse (eds), New Governance – New Democracy? Post-Devolution Wales Neil Selwyn and Stephen Gorard, The Information Age: Technology, Learning and Exclusion in Wales Graham Day, Making Sense of Wales: A Sociological Perspective Richard Rawlings, Delineating Wales: Constitutional, Legal and Administrative Aspects of National Devolution The Politics and Society in Wales Series examines issues of politics and government, and particularly the effects of devolution on policy-making and implementation, and the way in which Wales is governed as the National Assembly gains in maturity. It will also increase our knowledge and understanding of Welsh society and analyse the most important aspects of social and economic change in Wales. Where necessary, studies in the series will incorporate strong comparative elements which will allow a more fully informed appraisal of the condition of Wales. Pit and the Pendulum Prelims.qxd 02/03/04 13:34 Page iii POLITICS AND SOCIETY IN WALES The Pit and the Pendulum A COOPERATIVE FUTURE FOR WORK IN THE WELSH VALLEYS By MOLLY SCOTT CATO Published on behalf of the Social Science Committee of the Board of Celtic Studies of the University of Wales UNIVERSITY OF WALES PRESS CARDIFF 2004 Pit and the Pendulum Prelims.qxd 04/03/04 16:01 Page iv © Molly Scott Cato, 2004 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. -

PDFHS CD/Download Overview 100 Local War Memorials the CD Has Photographs of Almost 90% of the Memorials Plus Information on Their Current Location

PDFHS CD/Download Overview 100 Local War Memorials The CD has photographs of almost 90% of the memorials plus information on their current location. The Memorials - listed in their pre-1970 counties: Cambridgeshire: Benwick; Coates; Stanground –Church & Lampass Lodge of Oddfellows; Thorney, Turves; Whittlesey; 1st/2nd Battalions. Cambridgeshire Regiment Huntingdonshire: Elton; Farcet; Fletton-Church, Ex-Servicemen Club, Phorpres Club, (New F) Baptist Chapel, (Old F) United Methodist Chapel; Gt Stukeley; Huntingdon-All Saints & County Police Force, Kings Ripton, Lt Stukeley, Orton Longueville, Orton Waterville, Stilton, Upwood with Gt Ravely, Waternewton, Woodston, Yaxley Lincolnshire: Barholm; Baston; Braceborough; Crowland (x2); Deeping St James; Greatford; Langtoft; Market Deeping; Tallington; Uffington; West Deeping: Wilsthorpe; Northamptonshire: Barnwell; Collyweston; Easton on the Hill; Fotheringhay; Lutton; Tansor; Yarwell City of Peterborough: Albert Place Boys School; All Saints; Baker Perkins, Broadway Cemetery; Boer War; Book of Remembrance; Boy Scouts; Central Park (Our Jimmy); Co-op; Deacon School; Eastfield Cemetery; General Post Office; Hand & Heart Public House; Jedburghs; King’s School: Longthorpe; Memorial Hospital (Roll of Honour); Museum; Newark; Park Rd Chapel; Paston; St Barnabas; St John the Baptist (Church & Boys School); St Mark’s; St Mary’s; St Paul’s; St Peter’s College; Salvation Army; Special Constabulary; Wentworth St Chapel; Werrington; Westgate Chapel Soke of Peterborough: Bainton with Ashton; Barnack; Castor; Etton; Eye; Glinton; Helpston; Marholm; Maxey with Deeping Gate; Newborough with Borough Fen; Northborough; Peakirk; Thornhaugh; Ufford; Wittering. Pearl Assurance National Memorial (relocated from London to Lynch Wood, Peterborough) Broadway Cemetery, Peterborough (£10) This CD contains a record and index of all the readable gravestones in the Broadway Cemetery, Peterborough. -

Supplementary Planning Guidance: Affordable Housing Adopted March 2011 1

1. LDP Affordable housing 2011_Layout 1 12/07/2011 08:04 Page 1 Supplementary Planning Guidance: Affordable Housing Adopted March 2011 1. LDP Affordable housing 2011_Layout 1 12/07/2011 08:04 Page 2 1. LDP Affordable housing 2011_Layout 1 12/07/2011 08:04 Page 3 Affordable Housing ContentsContents 1 Introduction ..............................................................................4 2. Policy Context............................................................................4 3. Issues ........................................................................................8 3.1 Definition of Affordable Housing ........................................................8 3.2 Housing Needs......................................................................................8 4. Planning Considerations and Requirements................................9 4.1 Process ..................................................................................................9 4.2 On Site Provision ................................................................................10 4.3 Off Site Provision................................................................................11 4.4 Financial Contributions......................................................................11 5. Appendices ..............................................................................12 Appendix 1 – Glossary of Terms Appendix 2 – Map of LDP Strategy Areas Appendix 3 – List of Wards by Strategy Areas Appendix 4 – ”List of Registered Social Landlords (RSLs) Appendix -

Court Reform in England

Comments COURT REFORM IN ENGLAND A reading of the Beeching report' suggests that the English court reform which entered into force on 1 January 1972 was the result of purely domestic considerations. The members of the Commission make no reference to the civil law countries which Great Britain will join in an important economic and political regional arrangement. Yet even a cursory examination of the effects of the reform on the administration of justice in England and Wales suggests that English courts now resemble more closely their counterparts in Western Eu- rope. It should be stated at the outset that the new organization of Eng- lish courts is by no means the result of the 1971 Act alone. The Act crowned the work of various legislative measures which have brought gradual change for a period of well over a century, including the Judicature Acts 1873-75, the Interpretation Act 1889, the Supreme Court of Judicature (Consolidation) Act 1925, the Administration of Justice Act 1933, the County Courts Act 1934, the Criminal Appeal Act 1966 and the Criminal Law Act 1967. The reform culminates a prolonged process of response to social change affecting the legal structure in England. Its effect was to divorce the organization of the courts from tradition and history in order to achieve efficiency and to adapt the courts to new tasks and duties which they must meet in new social and economic conditions. While the earlier acts, including the 1966 Criminal Appeal Act, modernized the structure of the Supreme Court of Judicature, the 1971 Act extended modern court structure to the intermediate level, creating the new Crown Court, and provided for the regular admin- istration of justice in civil matters by the High Court in England and Wales, outside the Royal Courts in London.