The Permian Basin Field Trip

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROGER Y. ANDERSON Department of Geology, the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87106 WALTER E

ROGER Y. ANDERSON Department of Geology, The University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87106 WALTER E. DEAN, JR. Department of Geology, Syracuse University, Syracuse, New Yor\ 13210 DOUGLAS W. KIRKLAND Mobil Research and Development Corporation, Dallas, Texas 75221 HENRY I. SNIDER Department of Physical Sciences, Eastern Connecticut State College, Willimantic, Connecticut 06226 Permian Castile Varved Evaporite Sequence, West Texas and New Mexico ABSTRACT is a change from thinner undisturbed anhy- drite laminae to thicker anhydrite laminae that Laminations in the Upper Permian evaporite generally show a secondary or penecontem- sequence in the Delaware Basin appear in the poraneous nodular character, with about 1,000 preevaporite phase of the uppermost Bell to 3,000 units between major oscillations or Canyon Formation as alternations of siltstone nodular beds. These nodular zones are correla- and organic layers. The laminations then change tive throughout the area of study and underly character and composition upward to organi- halite when it is present. The halite layers cally laminated claystone, organically laminated alternate with anhydrite laminae, are generally calcite, the calcite-laminated anhydrite typical recrystallized, and have an average thickness of the Castile Formation, and finally to the of about 3 cm. The halite beds were once west anhydrite-laminated halite of the Castile and of their present occurrence in the basin but Salado. were dissolved, leaving beds of anhydrite Laminae are correlative for distances up to breccia. The onset and cessation of halite depo- 113 km (70.2 mi) and probably throughout sition in the basin was nearly synchronous. most of the basin. Each lamina is synchronous, The Anhydrite I and II Members thicken and each couplet of two laminated components gradually across the basin from west to east, is interpreted as representing an annual layer of whereas the Halite I, II, and III Members are sedimentation—a varve. -

DIAGENESIS of the BELL CANYON and CHERRY CANYON FORMATIONS (GUADALUPIAN), COYANOSA FIELD AREA, PECOS COUNTY, TEXAS by Katherine

Diagenesis of the Bell Canyon and Cherry Canyon Formations (Guadalupian), Coyanosa field area, Pecos County, Texas Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Kanschat, Katherine Ann Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 19:22:41 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/557840 DIAGENESIS OF THE BELL CANYON AND CHERRY CANYON FORMATIONS (GUADALUPIAN), COYANOSA FIELD AREA, PECOS COUNTY, TEXAS by Katherine Ann Kanschat A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF GEOSCIENCES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 8 1 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable with out special permission, provided that accurate acknowledge ment of source is made. Requests for permission for ex tended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major de partment or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judgment the proposed use of the material is in the inter ests of scholarship. -

Salt Caverns Studies

SALT CAVERN STUDIES - REGIONAL MAP OF SALT THICKNESS IN THE MIDLAND BASIN FINAL CONTRACT REPORT Prepared by Susan Hovorka for U.S. Department of Energy under contract number DE-AF22-96BC14978 Bureau of Economic Geology Noel Tyler, Director The University of Texas at Austin Austin, Texas 78713-8924 February 1997 CONTENTS Executive Summmy ....................... ..... ...................................................................... ...................... 1 Introduction ..................................................... .. .............................................................................. 1 Purpose .......................................................................................... ..................................... ............. 2 Methods ........................................................................................ .. ........... ...................................... 2 Structural Setting and Depositional Environments ......................................................................... 6 Salt Thickness ............................................................................................................................... 11 Depth to Top of Salt ...................................................................................................................... 14 Distribution of Salt in the Seven Rivers, Queen, and Grayburg Formations ................................ 16 Areas of Salt Thinning ................................................................................................................. -

Speleogenesis and Delineation of Megaporosity and Karst

Stephen F. Austin State University SFA ScholarWorks Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2016 Speleogenesis and Delineation of Megaporosity and Karst Geohazards Through Geologic Cave Mapping and LiDAR Analyses Associated with Infrastructure in Culberson County, Texas Jon T. Ehrhart Stephen F. Austin State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/etds Part of the Geology Commons, Hydrology Commons, and the Speleology Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Repository Citation Ehrhart, Jon T., "Speleogenesis and Delineation of Megaporosity and Karst Geohazards Through Geologic Cave Mapping and LiDAR Analyses Associated with Infrastructure in Culberson County, Texas" (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 66. https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/etds/66 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Speleogenesis and Delineation of Megaporosity and Karst Geohazards Through Geologic Cave Mapping and LiDAR Analyses Associated with Infrastructure in Culberson County, Texas Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This thesis is available at SFA ScholarWorks: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/etds/66 Speleogenesis and Delineation of Megaporosity and Karst Geohazards Through Geologic Cave Mapping and LiDAR Analyses Associated with Infrastructure in Culberson County, Texas By Jon Ehrhart, B.S. Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Stephen F. Austin State University In Partial Fulfillment Of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Science STEPHEN F. -

Karst in Evaporites in Southeastern New Mexico*

Waste Isolation Pilot Plant Compliance Certification Application Reference 27 Bachman, G. 0., 1987. Karst in Evaporites in Southeast~m New Mexico, SAND86-7078, Albuquerque, NM, Sandia National Laboratories. Submitted in accordance with 40 CPR §194.13, Submission of Reference Materials. ~I SAND86-7078 Distribution Unlimited Release Category UC-70 Printed September 1987 Karst in Evaporites in Southeastern New Mexico* SAND--86-7078 DE88 001315 George 0. Bachman, Consultant 4008 Hannett Avenue NE Albuquerque, NM 87110 Abstract Permian evaporites in southeastern New Mexico include gypsum, anhydrite, and salt, which are subject to both blanket and local, selective dissolution. Dissolution has produced many hundreds of individual karst features including collapse sinks, karst valleys, blind valleys, karst plains, caves, and breccia pipes. Dissolution began within some formations during Permian time and has been intermittent but continual ever since. Karst features other than blanket deposits of breccia are not preserved from the early episodes of dissolution, but some karst features preserved today-such as breccia pipes-are remnants of karst activity that was active at least as early as mid-Pleistocene time. Rainfall was much more abundant during Late Pleistocene time, and many features visible today may have been formed then. The drainage history of the Pecos River is related to extensive karstification of the Pecos Valley during mid-Pleistocene time. Large-scale stream piracy and dissolution of - salt in the subsurface resulted in major shifts and excavations in the channel. In spite of intensive groundwater studies that have been carried out in the region, major problems in groundwater in near-surface evaporite karst remain to be solved. -

Characteristics of the Boundary Between the Castile and Salado

Gharacteristicsofthe boundary between the Castile and SaladoFormations near the western edge of the Delaware Basin, southeasternNew Mexico by BethM. Madsenand 1mer B. Raup,U.S. Geological Survey, Box 25046, MS-939, Denver, C0 80225 Abstract 1050 posited in the DelawareBasin of southeast New Mexico and west Texasduring Late Per- Permian The contact between the Upper mian (Ochoan)time. In early investigations Castile and Salado Formations throughout and SaladoFormations were un- the Delaware Basin, southeastNew Mexico /-a(run,ouo the Castile differentiated, and the two formations were and west Texas,has been difficult to define EDDY / aou^r" because of facies chanqes from the basin called Castile by Richardson (1904).Cart- center to the western idge. Petrographic wright (1930)divided the sequenceinto the studies of core from a Phillips Petroleum i .,/ upper and lower parts of the Castileon the Company well, drilled in the westernDela- -r---| ,' . NEW MEXTCO basisof lithology and arealdistribution. Lang ware Basin, indicate that there are maior (1935) the name "Saladohalite" Perotf,um introduced mineralogical and textural differences be- ,/ rot company "n for the upper part of the sequence,and he and Salado Formations. / core hole'NM 3170'1 tween the Castile the term Castile for the lower part The Castile is primarilv laminated anhv- retained of the drite with calciteand dolomite.The Salado ( of the sequence.Lang placed the base DELAWARE BASIN Formation is also primarily anhydrite at the SaladoFormation at the base of potassium location of this corehole, but with abundant (polyhalite) mineralization. This proved to layers of magnesite.This magnesiteindi- be an unreliable marker becausethe zone of catesan increaseof magnesiumenrichment mineralization occupies different strati- in the basin brines, which later resulted in graphic positions in different areas. -

Dissolution of Permian Salado Salt During Salado Time in the Wink Area, Winkler County, Texas Kenneth S

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/44 Dissolution of Permian Salado salt during Salado time in the Wink area, Winkler County, Texas Kenneth S. Johnson, 1993, pp. 211-218 in: Carlsbad Region (New Mexico and West Texas), Love, D. W.; Hawley, J. W.; Kues, B. S.; Austin, G. S.; Lucas, S. G.; [eds.], New Mexico Geological Society 44th Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 357 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 1993 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content are available only in the printed guidebooks. -

Geologic Map of the Kitchen Cove 7.5-Minute Quadrangle, Eddy County, New Mexico by Colin T

Geologic Map of the Kitchen Cove 7.5-Minute Quadrangle, Eddy County, New Mexico By Colin T. Cikoski1 1New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources, 801 Leroy Place, Socorro, NM 87801 June 2019 New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources Open-file Digital Geologic Map OF-GM 276 Scale 1:24,000 This work was supported by the U.S. Geological Survey, National Cooperative Geologic Mapping Program (STATEMAP) under USGS Cooperative Agreement G18AC00201 and the New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources. New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources 801 Leroy Place, Socorro, New Mexico, 87801-4796 The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the author and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the U.S. Government or the State of New Mexico. Executive Summary The Kitchen Cove quadrangle lies along the northwestern margin of the Guadalupian Delaware basin southwest of Carlsbad, New Mexico. The oldest rocks exposed are Guadalupian (upper Permian) carbonate rocks of the Seven Rivers Formation of the Artesia Group, which is sequentially overlain by similar strata of the Yates and Tansill Formations of the same Group. Each of these consists dominantly of dolomitic beds with lesser fine-grained siliciclastic intervals, which accumulated in a marine or marginal-marine backreef or shelf environment. These strata grade laterally basinward (here, eastward) either at the surface or in the subsurface into the Capitan Limestone, a massive fossiliferous “reef complex” that lay along the Guadalupian Delaware basin margin and is locally exposed on the quadrangle at the mouths of Dark Canyon and Kitchen Cove. -

G-Eological^-^ Survey,' United States Department of the Interior, and the Texas State Board of Water Engineers

STaIE BOARD .OF WATER ENGINEERS C* S. Clark, Chairman A; H« Dunlapj Member i» W» Pritchett, Member TEXAS Pecos River Basin Volume II RECORDS OF WELLS AND SPRINGS AMD ANALYSES OF WATER IN LOVING-, WARD, REEVES AND NORTHERN PECOS COUNTIES By P. Eldon Dennis and Joe W. Lang Prepared in cooperation between the G-eological^-^ Survey,' United States Department of the Interior, and the Texas State Board of Water Engineers March 1941 STATE BOARD OF WATER ENGINEERS C. S. Clark, Chairman A. H. Dunlap, Member J. W. Pritchett, Member TEXAS PECOS RIVER BASIN VOLUME II Records of Wells and Springs and Analyses of Water in Loving, Ward, Reeves and Northern Pecos Counties By P. Eldon Dennis and Joe W. Lang Prepared in cooperation between the Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior, and the Texas State Board of Water Engineers March 1941 Contents Introduction . * 2 Records of wells and springs Ward County " ....... 3 Loving County »„...., . 27 Reeves County .,.. 37 * , Pecos County .?.*,. 81 Crane Gounty . 89 Drillers' logs Ward County 91 Loving County 108 Reeves County ,... 113 Pecos County . 131 Crane County . 139 Records of water levels Ward County 141 Loving County 146 Reeves Gounty . * 147 Pecos County 162 Analyses of well and spring water Vferd County .♥".. 163 Loving County ...... 166 Reeves County . » 167 Pecos County .- * 173 Illustrations Plate la Map of the Pecos Basin in Texas showing wells and springs Records of wells and springs, drillers' logs, water level measurements, and analyses of water from wells and springs in the Pecos River Basin in Texas.- Introduction 3y A. N. -

Epigene and Hypogene Karst Manifestations of the Castile Formation: Eddy County, New Mexico and Culberson County, Texas, USA

Stephen F. Austin State University SFA ScholarWorks Faculty Publications Department of Geology 7-2008 Epigene and Hypogene Karst Manifestations of the Castile Formation: Eddy County, New Mexico and Culberson County, Texas, USA Kevin W. Stafford College of Sciences and Mathematics, Department of Geology, Stephen F. Austin State University, [email protected] Raymond Nance Laura Rosales-Lagarde National Cave and Karst Research Institute, 400 Commerce Drive, Carlsbad, NM Penelope J. Boston Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/geology Part of the Geology Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Repository Citation Stafford, Kevin W.; Nance, Raymond; Rosales-Lagarde, Laura; and Boston, Penelope J., "Epigene and Hypogene Karst Manifestations of the Castile Formation: Eddy County, New Mexico and Culberson County, Texas, USA" (2008). Faculty Publications. 12. https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/geology/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Geology at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. International Journal of Speleology 37 (2) 83-98 Bologna (Italy) July 2008 Available online at www.ijs.speleo.it International Journal of Speleology Official Journal of Union Internationale de Spéléologie Epigene and Hypogene Gypsum Karst Manifestations of the Castile Formation:Eddy County, New Mexico and Culberson County, Texas, USA Kevin W. Stafford1,2, Raymond Nance3, Laura Rosales-Lagarde1,2, and Penelope J. Boston1,2 Abstract: Stafford K., Nance R., Rosales-Lagarde L. and Boston P.J. 2008. Epigene and Hypogene Gypsum Karst Manifestations of the Castile Formation: Eddy County, New Mexico and Culberson County, Texas, USA. -

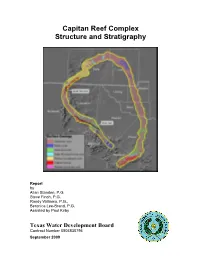

Capitan Reef Complex Structure and Stratigraphy

Capitan Reef Complex Structure and Stratigraphy Report by Allan Standen, P.G. Steve Finch, P.G. Randy Williams, P.G., Beronica Lee-Brand, P.G. Assisted by Paul Kirby Texas Water Development Board Contract Number 0804830794 September 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Executive summary....................................................................................................................1 2. Introduction................................................................................................................................2 3. Study area geology.....................................................................................................................4 3.1 Stratigraphy ........................................................................................................................4 3.1.1 Bone Spring Limestone...........................................................................................9 3.1.2 San Andres Formation ............................................................................................9 3.1.3 Delaware Mountain Group .....................................................................................9 3.1.4 Capitan Reef Complex..........................................................................................10 3.1.5 Artesia Group........................................................................................................11 3.1.6 Castile and Salado Formations..............................................................................11 3.1.7 Rustler Formation -

Geologic Notes on the Delaware Basin

Circular 63 • Geologic Notes on the Delaware Basin by leon Haigler United State s G e ological Surve y NEW MEXICO INSTITUTE OF MINING AND TECHNOLOGY E. J. Workman, President STATE BUREAU OF MINES AND MINERAL RESOURCES A. J. Thompson, Director CIRCULAR 63 GEOLOGIC NOTES ON THE DELAWARE BASIN by Leon Haigler United States Geological Survey Published in cooperation with the United States Geological Survey 1962 STATE BUREAU OF MINES AND MINERAL RESOURCES NEW MEXICO INSTITUTE OF MINING AND TECHNOLOGY CAMPUS STATION SOCORRO, NEW MEXICO NEW MEXICO INSTITUTE OF MINING & TECHNOLOGY E. J. Workman, President STATE BUREAU OF MINES & MINERAL RESOURCES Alvin J. Thompson, Director THE REGENTS MEMBERS EX OFFICIO The Honorable Edwin L. Mechem Governor of New Mexico Tom Wiley Superintendent of Public Instruction APPOINTED MEMBERS William G. Abbott Hobbs Holm 0. Bursum, Jr. Socorro Thomas M. Cramer Carls bad Frank C. DiLuzio . Albuquerque Eva M. Larrazolo (Mrs. Paul F.) Albuquerque For sale by the New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources Campus Station, Socorro, New Mexico Price $1.00 Contents ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION .2 STRUCTURAL FEATURES .3 Stratigraphy 4 Ordovician System .4 Simpson. Group equivalent .4 Montoya Dolomite .5 Silurian(?) and Devonian(?) systems .5 Devonian and Mississippian systems .6 Woodford Shale equivalent .6 Mississippian System 7 Pennsylvanian System .7 Permian System .8 Hueco Limestone 8 Bone Spring Limestone .9 Delaware Mountain Group .9 Permian back-reef or shelf formations . 10 Permian reefs . 10 Salado and Castile formations, undifferentiated . 11 Rustler Formation . 11 Post-Rustler Formation . 11 OIL AND GAS . 12 111 REFERENCES. .13 PLATE 1. East-west cross section through the Delaware basin of New Mexico in pocket iv Abstract The Delaware basin of New Mexico lies in Eddy and Lea counties, New Mexico, and contains about the northern one fourth of the total area of the Delaware basin.