Abstract TAYLOR, BENJAMIN ROSS. The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Taylor: Making Music and Memories by John Fries

Pittsburgh Boomers | August 2005 James Taylor: Making Music and Memories By John Fries If you went to high school during the 1970's, as I did, you'll recall a lot of really great music -- on the radio, in the school cafeteria at lunchtime, and on the eight track tapes you punched into your car dashboards at night while driving around. While the musical landscape offered something for everyone, much of it seemed to fall into two distinct categories: straight-ahead rock and top 40 pop. Here in Pittsburgh, we were either tuned to Trevor Ley playing Led Zeppelin or Pink Floyd on 'DVE or listening to the "New Sound of 13Q," which played a wide and eclectic mix of whatever was in the top 40 at the time. The top hits of the day were listed each week in the pocket-sized "hit parades" KQV and 13Q published and provided for free in local record stores. The list could include any combination of rock, power pop, country, rhythm and blues, vocalists, the occasional novelty record, and that 70's radio staple known as the singer-songwriter. Remember them? The mellow music makers who played guitar or piano, wrote meaningful, introspective lyrics, and served up gentle melodies? The singer-songwriter sections of our 45 collections included titles by such artists as Jackson Browne, Neil Young, Carole King, Joni Mitchell, John Denver, Paul Simon and a West Coast band of country rock upstarts called the Eagles. Although they were - and are -- all great artists, James Taylor became the undisputed king of the genre. -

Dolemite Is My Name

DOLEMITE IS MY NAME Written by Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski FINAL IN THE BLACK We hear Marvin Gaye's "What's Goin' On" playing softly. VOICE I ain't lying. People love me. INT. DOLPHIN'S - DAY CU of a beat-up record from the 1950s. On the paper cover is a VERY YOUNG Rudy, in a tuxedo. It says "Rudy Moore - BUGGY RIDE" RUDY You play this, folks gonna start hoppin' and squirmin', just like back in the day. A hand lifts the record up to the face of RUDY RAY MOORE, late '40s, black, sweet, determined. RUDY When I sang this on stage, I swear to God, people fainted! Ambulance man was picking them off the floor! When I had a gig, the promoter would warn the hospital: "Rudy's on tonight -- you're gonna be carrying bodies out of the motherfucking club!" We see that we are in a RADIO BOOTH. A sign blinks "On The Air." The DJ, ROJ, frowns at the record. ROJ "Buggy Ride"? RUDY Wasn't no small-time shit. ROJ GodDAMN, Rudy! That record's 1000 years old! I've got Marvin Gaye singin' "Let's Get It On"! I can't be playin' no "Buggy Ride." (beat) Look, I have 60 seconds. I have to cue the next tune. Hm! Rudy bites his lip and walks away. Roj tries to go back to his job. He reaches for a Sly Stone single -- when Rudy suddenly bounds back up. RUDY How about "Step It Up and Go"? That's a real catchy rhythm-and-blues number. -

Program for the Elixir of Love

DONIZETTI’S THE ELIXIR OF LOVE A potent potion to drive devotion APRIL 21, 24, 27, 29, 2018 STUDENT MATINEE: APRIL 26, 2018 BENEDUM CENTER 2017-18 SEASON TABLE OF CONTENTS THE ELIXIR EstatementJEWELRY OF LOVE (L’elisir d’amore) Set the stage for compliments and make a statement Music by Gaetano Donizetti every time you wear a piece of fine jewelry from Libretto by Felice Romani, after Eugène Scribe’s libretto for Daniel Auber’s Le philtre (1831) our Vintage & Contemporary Estate Collection. Affordable luxury that steals the spotlight. 2 .............Letter From Our Board Leadership Michele Fabrizi 3 .............Letter From Our General Director Board Chair 5 .............The Cast Gene Welsh 7 .............Synopsis Board President Christopher Hahn 11 ............Artist Biographies General Director 22 ...........Director’s Note Antony Walker 24 ...........Learn About Opera Music Director 25 ...........Student Matinee 26 ...........The Monteverdi Society Allison M. Ruppert Managing Editor 27 ............Board of Directors Platinum rings featuring Greenawalt Design LLC Rubies, Pink Tourmaline, 31 ............Annual Fund Listings Graphic Design and Precious Topaz. To schedule 38 ...........Orchestra your advertising in Pittsburgh Opera’s Authentic • Curated • Quality 39 ...........Chorus and Supernumeraries program, please call 412-471-1497 or VINTAGE & CONTEMPORARY 43 ...........Staff and Volunteers email advertising@ culturaldistrict.org. MOSES 44 ...........Benedum Directory Jewelers SINCE 1949 This program is published by Pittsburgh Opera, Inc., 2425 Liberty Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15222. EstateJEWELRY COLLECTION Phone: 412-281-0912; Fax 412-281-4324; Website www.pittsburghopera.org. Celebrating 69 years in business! All correspondence should be sent to the above address. Pittsburgh Opera assumes no responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts. Articles may be reprinted with permission. -

Kourier Document Setup 6-13-19

Kourier ALABAMA DISTRICT Summer 2019 Published by Alabama Kiwanis Foundation 28 pages District Convention is Aug. 2-4 By Patrice Stewart president of the Kiwanis Club of Kiwanis Kourier editor Huntsville and chairman of the con- It’s almost time to celebrate in vention. “We asked to host this year Huntsville, where the 101st Alabama because of our club’s 100th anniver- District Convention will be held Aug. sary. Huntsville is growing, and we 2-4 at Embassy Suites. want to show off our city.” The Kiwanis Club of Huntsville will The Huntsville club must receive serve as the host club, and Kiwanians other Kiwanis clubs formed that year registrations by July 26 to give meal and guests from around the state are will also be recognized at this conven- numbers to the hotel. invited to join in celebrating the club’s tion. Huntsville Kiwanians and district 100th anniversary. This Huntsville club “We are looking forward to hosting leaders have planned several speakers was organized July 14, 1919; several the whole district,” said Marc Byers, (See HUNTSVILLE, Page 5) Scenes from Kiwanis International Convention, from President-elect Vigneron from the Belgium-Luxembourg left: Kiwanis Club of Montgomery officers Sam Johnson District; and KI Executive Director Stan Soderstrom, left, and John Hutcheson, Kiwanis International President- greets Alabama Past Governor Armand St. Raymond, who elect Daniel Vigneron and Alabama Kiwanis Governor has been appointed to the Kiwanis Children’s Fund board Ben Taylor with two gold plaques for top Signature Proj- beginning Oct. 1. Soderstrom will be the luncheon ect; Alabama Governor-elect Bob Brown, left, meets with speaker at the District Convention in Huntsville Aug. -

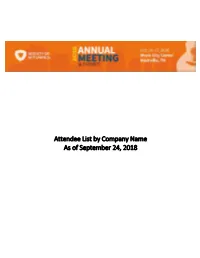

Attendee List by Company Name

Attendee List by Company Name As of September 24, 2018 George Hansen Art Lewis Benjamin Roberts A M Best Company AARP Services Inc ABS Group Oldwick, NJ Washington, DC Knoxville, TN Bonnie Birns Ross Bradshaw Tim Eddy Accenture Accenture Accenture Jericho, NY North Brunswick, NJ Tampa, FL Bill Luo Philip Moreland Paul Pflieger Accenture Accenture Accenture Franklin Park, NJ Denville, NJ Minneapolis, MN Steven de Jong Kevin Pledge Stephen Camilli Acceptiv Acceptiv ACTEX Learning Auckland, New Zealand Toronto, ON New Hartford, CT Jennifer Hart Emil Chacko Aimee Kaye Actuarial Careers Actuarial Careers Actuarial Careers Inc White Plains, NY White Plains, NY White Plains, NY Barbara Roman Jesse West Ted Jackness Actuarial Careers Inc Actuarial Careers Inc Actuarial Careers, Inc. White Plains, NY White Plains, NY White Plains, NY Tim Cardinal Ben Wolzenski Edward Kuo Actuarial Compass Actuarial Innovations, LLC Actuarial Perspective Inc. Morrow, OH Saint Louis, MO Mississauga, ON Nate Campbell Bob Crompton John Hegstrom Actuarial Resources Corporation Actuarial Resources Corporation Actuarial Resources Corporation Overland Park, KS Alpharetta, GA San Antonio, TX Roger Loomis Craig Maly John Marsteller Actuarial Resources Corporation Actuarial Resources Corporation Actuarial Resources Corporation Overland Park, KS Overland Park, KS Indianapolis, IN Jim Merwald Robert Peterson Tom Schroeder Actuarial Resources Corporation Actuarial Resources Corporation Actuarial Resources Corporation Overland Park, KS Overland Park, KS Overland Park, KS Eric -

The James Taylor Encyclopedia

The James Taylor Encyclopedia An unofficial compendium for JT’s biggest fans Joel Risberg GeekTV Press Copyright 2005 by Joel Risberg All rights reserved Published 2005 Printed in the United States of America James Taylor Online www.james-taylor.com [email protected] Cover photo by Joana Franca. This book is not approved or endorsed by James Taylor, his record labels, or his management. For Sandra, who brings me snacks. CONTENTS BIOGRAPHY 1 TIMELINE 16 SONG ORIGINS 27 STUDIO ALBUMS 31 SINGLES 43 WORK ON OTHER ALBUMS 44 OTHER COMPOSITIONS 51 CONCERT VIDEOS 52 SINGLE-SONG MUSIC VIDEOS 57 APPEARANCES IN OTHER VIDEOS 58 MISCELLANEOUS WORK 59 NON-U.S. ALBUMS 60 BOOTLEGS 63 CONCERTS ON TELEVISION 70 RADIO APPEARANCES 74 MAJOR LIVE PERFORMANCES 75 TV APPEARANCES 76 MAJOR ARTICLES AND INTERVIEWS 83 SHEET MUSIC AND MUSIC BOOKS 87 SAMPLE SET LISTS 89 JT’S FAMILY 92 RECORDINGS BY JT ALUMNI 96 POINTERS 100 1971 Time cover story – and nearly every piece of writing about James Taylor since then – characterized the musician Aas a troubled soul and the inevitable product of a family of means that expected quite a lot of its kids. To some extent, it was true. James did find inspiration for much of his life’s work in his emotional torment and the many years he spent fighting drug addiction and depression. And he did hail from an affluent, musically talented family that could afford to send its progeny to exclusive prep schools and expensive private mental hospitals. But now James Taylor in his fifties has the benefit of hindsight to moderate any lingering grudges against a press that persistently pigeonholed him – first as a sort of Kurt Cobain of his day, and much later as a sleepy crooner with his most creative years behind him. -

A Tramp Through the Bret Harte Country

A Tramp Through the Bret Harte Country Thomas Dykes Beasley A Tramp Through the Bret Harte Country Table of Contents A Tramp Through the Bret Harte Country...........................................................................................................1 Thomas Dykes Beasley..................................................................................................................................1 Foreword........................................................................................................................................................1 Preface............................................................................................................................................................2 Chapter I.........................................................................................................................................................3 Chapter II.......................................................................................................................................................4 Chapter III......................................................................................................................................................6 Chapter IV....................................................................................................................................................10 Chapter V.....................................................................................................................................................13 Chapter -

Undergraduate.Pdf

Commencement 2020 t UNDERGRADUATE STUDENT EDITION 1 Commencement 2020 t CONTENTS 3 Message from the University President 4 College of Community and Public Affairs 8 Decker College of Nursing and Health Sciences 13 Harpur College of Arts and Sciences 30 School of Management 36 Thomas J. Watson School of Engineering and Applied Science 43 Honors and Special Programs 60 About Binghamton University 63 Trustees, Council and Administration 2 MESSAGE FROM THE UNIVERSITY PRESIDENT MESSAGE FROM THE UNIVERSITY PRESIDENT raduates, parents and friends: Commencement is always the highlight of the academic year, for the students we are honoring, especially, but also for the faculty and staff who have Ghelped our students achieve so much. When the COVID-19 pandemic abruptly changed our lives this spring, sending students home and curtailing so many of the activities we all would have experienced had they remained on campus, most painful was the postponement of the University’s Commencement exercises that are traditionally the highlight of the academic year. Our graduates have gained the experiences and knowledge that their careers and future engagements will demand of them. Ours is a campus where students learn by doing, and our graduates have already proven themselves — winning prestigious case competitions and grants, publishing papers that have gained acclaim from scientists and scholars, and bettering their communities through hands-on internships and practicums. Outside the classroom, they have embraced their responsibilities as active members of the community. They’ve raised funds to combat deadly disease, provided food for the hungry, taught younger students in local schools and traveled across the globe to work with and learn from their international peers. -

“A Rare Diamond”, “A Voice Blessed”, “A Singer Destined for Great Things” “A Voice of Great Emotional Resonance”

Described by the US and British press as “A rare diamond”, “A voice blessed”, “A singer destined for great things” “A voice of great emotional resonance” ”Brave and original.” - The Guardian “Shines with authentic light” – American Songwriter “A voice that is both majestic and heartwarming“- Huffington Post “A star” - Billboard Magazine Athena keeps touching peoples’ hearts with her powerfully emotive voice. Athena Andreadis is one of those people who live and breathe and think and talk about music and she writes with the same sort of direct focus. During a one hour Channel 5 / Sky Arts documentary made about her in the UK, legendary songwriter Chris Difford (Squeeze) described Athena as someone who, “writes and sings from the heart. She doesn't need to be packaged by anyone – she is simply and beautifully her." She has the same sort of clear artistic vision that marks out Billie Eilish or Adele or John Legend and it’s matched with a fresh, limitless ambition. Born in London to Greek parents, Athena’s mother would sing her to sleep. Despite all the music around the house, the young Athena was encouraged to study business, so she headed to Bath University but continued performing. After securing a First Class Degree in Business, Athena enrolled at Trinity College, London, where she graduated from with two post-graduate degrees in Classical and Jazz Voice. Her consistent performing throughout her school years inevitably lead to Athena recording her debut album, Breathe With Me, which drew many excellent reviews, indeed The Guardian commenting that she was “Brave and original. -

South Hill Town Council Regular Meeting Minutes

SOUTH HILL TOWN COUNCIL REGULAR MEETING MINUTES MONDAY, JUNE 14, 2021, 7:00 P.M. The regular monthly meeting of the South Hill Town Council was held on Monday, June 14, 2021 at 7:00 p.m. in the Council Chambers of the South Hill Town Hall located at 211 S. Mecklenburg Avenue, South Hill, Virginia 23970. The meeting was also available livestream via YouTube. Anna Cratch took the minutes. 1. CALL TO ORDER Honorable Mayor Dean Marion called the regular meeting to order at 7:00 p.m. 2. INVOCATION Mayor Marion rendered the invocation. 3. ROLL CALL Mayor Marion called upon Anna Cratch to call the roll, which was as follows: A. Council Members Lillie Feggins-Boone Alex Graham Gavin L. Honeycutt Delores B. Luster W.M. “Mike” Moody Shep Moss G. Ben Taylor Joseph E. Taylor, Jr. B. Staff in Attendance Stuart Bowen, Police Chief Kim Callis, Town Manager Anna Cratch, Town Clerk Sheila Cutrell, Dir. of Finance and Admin. C.J. Dean, Dir. of Municipal Services David Hash, Code Compliance Official Carol Hutchinson, HR Manager Brent Morris, Business Devt. Manager 4. APPROVAL OF MINUTES – MAY 10, 2021 A motion was made by Councilman Honeycutt, second by Councilman Moody, to approve the minutes of the regular meeting held on May 10, 2021 as distributed by Anna Cratch. Motion carried unanimously. 5. APPRECIATION TO LOGAN MATHEWS Although Logan Mathews was absent, on behalf of the South Hill Town Council and staff, Mayor Marion read a letter of appreciation to him for his assistance while serving as an intern with livestreaming meetings during the unprecedented events of the COVID-19 Pandemic. -

Been There Done That

Sleepy Men Staring at the Sky by Ben Taylor Ben Taylor Thesis: Sleepy Men Staring at the Sky Been There Done That Will and Francis got anxiously down from the car and sought a path forward, seeing themselves nearly boxed in by a network of puddles and patches of muddy grass, noting that they would have to hop from one dry bit of pavement to the next. “I think this probably takes the cake, Francis,” Will said. “For what?” She started laughing. “What cake?” Then she stopped herself. “You mean the puddles?” she said, as she maneuvered around a particularly long one. “No...Henry, I mean. Not that I ever know what to expect from him, sure, but he didn’t say a word to me the whole drive down here.” “He’s in a stage, I think,” she said, shrugging. “What does he have to be in a stage about?” “Well, I don’t know, but at least that earthquake happened.” They split to either side of a puddle, and both 2 Ben Taylor Thesis: Sleepy Men Staring at the Sky sped up to reach the end. “It’s not like his house fell down on top of him.” “I guess not, since he’s not flattened and he’s here with us, but that doesn’t mean it wasn’t a big deal,” she said. “How could it not be?” “He hasn’t said anything about it. And what was it, like 5 months ago?” “Still, he just got home, he could be going through anything.” “How exotic is Chile, anyway?” Will said. -

2008-09 2008-09 ANNUAL REPORT 2008-09 Annual Report Director’S Address

UANNUALniversity of Illinois REPORT 1 2008-09 2008-09 ANNUAL REPORT 2008-09 Annual Report Director’s Address ............................................................................................................3 The Olympics ................................................................................................................4-5 Men’s Gymnastics .........................................................................................................6-7 Men’s Golf .....................................................................................................................8-9 Men’s Basketball ....................................................................................................... 10-11 Women’s Cross Country.......................................................................................... 12-13 Wrestling .................................................................................................................... 14-15 Men’s Tennis ............................................................................................................. 16-17 Women’s Gymnastics ............................................................................................... 18-19 Volleyball ................................................................................................................... 20-21 Softball ....................................................................................................................... 22-23 Women’s Track and Field .......................................................................................