E Status, Rights and Treatment of Persons with Disabilities Within Customary Legal Frameworks in Uganda a Study of Mukono District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MUKONO BFP.Pdf

Local Government Budget Framework Paper Vote: 542 Mukono District Structure of Budget Framework Paper Foreword Executive Summary A: Revenue Performance and Plans B: Summary of Department Performance and Plans by Workplan C: Draft Annual Workplan Outputs for 2015/16 Page 1 Local Government Budget Framework Paper Vote: 542 Mukono District Foreword The District expects an annual budget of shs. 28,090,331,000 of which central grants contribute over 94.2% Donor funding 1.6% and local revenue 4.2%. The expected expenditure per department is as follows: Administration=3.8%, Finance= 4.6%, statutory bodies=3.4%, Production=8.9%, Health care= 10.8%, Education and sports= 57.1%, Works=3.8%, Water = 2.3%, Natural resource=1%, Community based=1.7%, Planning unit=2.2%, Internal audit=0 .4%. LUKE L. L. LOKUDA CHIEF ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICER MUKONO DISTRICT Page 2 Local Government Budget Framework Paper Vote: 542 Mukono District Executive Summary Revenue Performance and Plans 2014/15 2015/16 Approved Budget Receipts by End Proposed Budget September UShs 000's 1. Locally Raised Revenues 1,338,909 233,424 1,338,909 2a. Discretionary Government Transfers 2,860,770 715,193 2,860,770 2b. Conditional Government Transfers 25,300,550 6,174,496 25,300,550 2c. Other Government Transfers 2,759,364 1,256,460 1,734,554 3. Local Development Grant 677,694 169,423 677,694 4. Donor Funding 529,677 181,770 0 Total Revenues 33,466,963 8,730,765 31,912,477 Revenue Performance in the first quarter of 2014/15 Planned Revenues for 2015/16 Expenditure Performance and Plans 2014/15 -

October 21 2017 Thesis New Changes Tracked

The Status, Rights and Treatment of Persons with Disabilities within Customary Legal Frameworks in Uganda: A Study of Mukono District By David Brian Dennison BA (honours), MBA, JD (cum laude) (University of Georgia, USA) Thesis Presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Private TownLaw Faculty of Law UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN Cape of Date of submission: 31 October 2017 Supervisor: Professor Chuma Himonga University Department of Private Law University of Cape Town The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derivedTown from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes Capeonly. of Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University The copyright for this thesis rests with the University of Cape Town. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgment of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non-commercial research purposes only. "ii ABSTRACT Thesis Title: The Status, Rights and Treatment of Persons with Disabilities within Customary Legal Frameworks in Uganda: A Study of Mukono District Submitted by: David Brian Dennison on 31 October 2017 This thesis addresses the question: How do customary legal frameworks impact the status, rights and treatment of persons with disabilities? It is motivated by two underlying premises. First, customary legal frameworks are highly consequential in Sub-Saharan contexts. -

UGANDA: PLANNING MAP (Details)

IMU, UNOCHA Uganda http://www.ugandaclusters.ug http://ochaonline.un.org UGANDA: PLANNING MAP (Details) SUDAN NARENGEPAK KARENGA KATHILE KIDEPO NP !( NGACINO !( LOPULINGI KATHILE AGORO AGU FR PABAR AGORO !( !( KAMION !( Apoka TULIA PAMUJO !( KAWALAKOL RANGELAND ! KEI FR DIBOLYEC !( KERWA !( RUDI LOKWAKARAMOE !( POTIKA !( !( PAWACH METU LELAPWOT LAWIYE West PAWOR KALAPATA MIDIGO NYAPEA FR LOKORI KAABONG Moyo KAPALATA LODIKO ELENDEREA PAJAKIRI (! KAPEDO Dodoth !( PAMERI LAMWO FR LOTIM MOYO TC LICWAR KAPEDO (! WANDI EBWEA VUURA !( CHAKULYA KEI ! !( !( !( !( PARACELE !( KAMACHARIKOL INGILE Moyo AYUU POBURA NARIAMAOI !( !( LOKUNG Madi RANGELAND LEFORI ALALI OKUTI LOYORO AYIPE ORAA PAWAJA Opei MADI NAPORE MORUKORI GWERE MOYO PAMOYI PARAPONO ! MOROTO Nimule OPEI PALAJA !( ALURU ! !( LOKERUI PAMODO MIGO PAKALABULE KULUBA YUMBE PANGIRA LOKOLIA !( !( PANYANGA ELEGU PADWAT PALUGA !( !( KARENGA !( KOCHI LAMA KAL LOKIAL KAABONG TEUSO Laropi !( !( LIMIDIA POBEL LOPEDO DUFILE !( !( PALOGA LOMERIS/KABONG KOBOKO MASALOA LAROPI ! OLEBE MOCHA KATUM LOSONGOLO AWOBA !( !( !( DUFILE !( ORABA LIRI PALABEK KITENY SANGAR MONODU LUDARA OMBACHI LAROPI ELEGU OKOL !( (! !( !( !( KAL AKURUMOU KOMURIA MOYO LAROPI OMI Lamwo !( KULUBA Koboko PODO LIRI KAL PALORINYA DUFILE (! PADIBE Kaabong LOBONGIA !( LUDARA !( !( PANYANGA !( !( NYOKE ABAKADYAK BUNGU !( OROM KAABONG! TC !( GIMERE LAROPI PADWAT EAST !( KERILA BIAFRA !( LONGIRA PENA MINIKI Aringa!( ROMOGI PALORINYA JIHWA !( LAMWO KULUYE KATATWO !( PIRE BAMURE ORINJI (! BARINGA PALABEK WANGTIT OKOL KINGABA !( LEGU MINIKI -

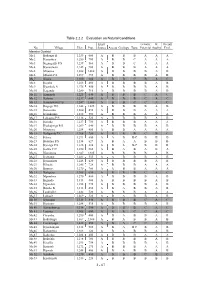

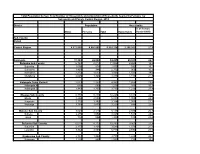

Table 2.2.2 Evaluation on Natural Conditions

Table 2.2.2 Evaluation on Natural Conditions Exist. G-water W. Overall No. Village Elev. Pop. Source Access Geology Topo. Potential Auality Eval. Masaka Destrict Ma 1 Bukango B 1,239 600 A B B B A A A Ma 2 Kasambya 1,250 700 A B B C A A A Ma 3 Kigangazzi P/S 1,239 560 A B B C A A A Ma 4 Kyawamala 1,245 900 A B B B A A A Ma 5 Mijunwa 1,208 1,060 A B B B B A B Ma 6 Mbirizi P/S 1,299 455 A B B B B A B Ma 7 Kisala 1,300 380 A B B C B A C Ma 8 Kigaba 1,206 400 A B B B B A B Ma 9 Kyankole A 1,276 450 A B B B B A B Ma 10 Kagando 1,280 710 A B B B B A B Ma 11 Kamanda 1,225 640 A B B B C A C Ma 12 Katoma 1,217 440 A B B B C A C Ma 13 Kassebwavu P/S 1,247 1,000 A B B C C A C Ma 14 Kagogo H/C 1,248 1,025 A B B B B A B Ma 15 Buwembo 1,280 490 A B B B A A A Ma 16 Kyankonko 1,272 590 A B B B A A A Ma 17 Lukaawa P/S 1,316 520 A B B B B A B Ma 18 Kirinda 1,237 750 A B B B A A A Ma 19 Kyakajwiga P/S 1,209 640 A B B B B A B Ma 20 Miteteero 1,258 480 A B B A A A A Ma 21 Kaligondo T/C 1,308 780 A B B B C B C Ma 22 Kitwa 1,291 600 A A B B-C B B B Ma 23 Bbuuliro P/S 1,134 627 A B A A B B B Ma 24 Kyesiga P/S 1,228 888 A B A B-C B B B Ma 25 Katwe T/C 1,250 380 A B A B A B A Ma 26 Nsangamo 1,287 1,485 A B B B B A B Ma 27 Kyetume 1,281 535 A A B B B A B Ma 28 Kyamakata 1,248 620 A B B B B A B Ma 29 Kibaale 1,246 728 A B B B A A A Ma 30 Bunyere 1,270 780 A A B B A A A Ma 31 Kalegero 1,305 620 A B B B C A C Ma 32 Mpembwe 1,270 400 A B B B B A B Ma 33 Bigando 1,313 400 A B B B B A B Ma 34 Ngondati 1,258 775 A B B B B A B Ma 35 Busibo B 1,313 455 A B A B B A B Ma -

Is Uganda's "No Party" System Discriminatory Against Women and a Violation of International Law? Amy N

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Brooklyn Law School: BrooklynWorks Brooklyn Journal of International Law Volume 27 Issue 3 SYMPOSIUM: Article 11 International Telecommunications Law in the Post- Deregulatory Landscape 2002 Is Uganda's "No Party" System Discriminatory Against Women and a Violation of International Law? Amy N. Lippincott Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil Recommended Citation Amy N. Lippincott, Is Uganda's "No Party" System Discriminatory Against Women and a Violation of International Law?, 27 Brook. J. Int'l L. (2002). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil/vol27/iss3/11 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. IS UGANDA'S "NO-PARTY" SYSTEM DISCRIMINATORY AGAINST WOMEN AND A VIOLATION OF INTERNATIONAL LAW? I. INTRODUCTION In the wake of colonialism, democratic governments have re- cently been established in many African countries. Under the watchful- eye of the international community, these couhtries have frequently taken steps to address widespread allegations of human rights abuses and discrimination, including estab- lishing and amending their constitutions and participating in various international conventions and treaties. While these documented efforts made by African nations to eliminate dis- crimination are commendable, it is crucial -

Vote:542 Mukono District Quarter1

Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2019/20 Vote:542 Mukono District Quarter1 Terms and Conditions I hereby submit Quarter 1 performance progress report. This is in accordance with Paragraph 8 of the letter appointing me as an Accounting Officer for Vote:542 Mukono District for FY 2019/20. I confirm that the information provided in this report represents the actual performance achieved by the Local Government for the period under review. Nkata. B. James Date: 05/12/2019 cc. The LCV Chairperson (District) / The Mayor (Municipality) 1 Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2019/20 Vote:542 Mukono District Quarter1 Summary: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures Overall Revenue Performance Ushs Thousands Approved Budget Cumulative Receipts % of Budget Received Locally Raised Revenues 2,165,188 541,297 25% Discretionary Government 4,425,042 1,190,092 27% Transfers Conditional Government Transfers 35,247,076 9,611,327 27% Other Government Transfers 3,791,074 663,098 17% External Financing 256,500 42,410 17% Total Revenues shares 45,884,879 12,048,224 26% Overall Expenditure Performance by Workplan Ushs Thousands Approved Cumulative Cumulative % Budget % Budget % Releases Budget Releases Expenditure Released Spent Spent Administration 7,460,303 2,150,500 1,922,394 29% 26% 89% Finance 469,132 114,856 85,192 24% 18% 74% Statutory Bodies 1,007,284 252,999 177,696 25% 18% 70% Production and Marketing 2,330,532 595,709 469,467 26% 20% 79% Health 6,530,010 1,841,368 1,760,879 28% 27% 96% Education 24,190,088 6,039,281 5,341,989 -

Impact of the Black Twig Borer on Robusta Coffee in Mukono and Kayunga Districts, Central Uganda

Journal of Animal & Plant Sciences, 2009. Vol. 3, Issue 1: 163 - 169. Publication date: 15 May 2009, http://www.biosciences.elewa.org/JAPS; ISSN 2071 - 7024 JAPS Impact of the black twig borer on Robusta coffee in Mukono and Kayunga districts, central Uganda Egonyu JP 1§, Kucel P 1, Kangire A 1, Sewaya F 2. and Nkugwa C 2 1National Crops Resources Research Institute (NaCRRI)/Coffee Research Centre (COREC), P.O Box 185, Mukono, Uganda; Uganda Coffee Development Authority, P.O. Box 7267, Kampala, Uganda § Corresponding author email: [email protected] Key words: Black twig borer, coffee, incidence, damage 1 SUMMARY An outbreak of a “serious” pest of coffee was reported in Mukono and Kayunga districts in central Uganda in December 2008. In response, a survey was carried out in the two districts to determine the identity, spread, incidence and damage caused by the pest. The pest was preliminarily identified as the black twig borer, Xylosandrus compactus (Eichhoff), which was found on coffee in both districts infesting 37.5% of the surveyed Robusta coffee farms. The infestation in Mukono was higher than in Kayunga, being 50 and 8.3%, respectively. The percentage of trees attacked (incidence) in the two districts was 21.2, with 3.7% of their twigs bored (damaged). Mukono district had a much higher incidence (35.3%) and damage (4.9%) compared to Kayunga with 0.8% for both parameters. The most serious damage was recorded in Namuganga and Nabbaale subcounties in Mukono district, the apparent epicentre of the outbreak. It was evident that the pest was spreading to other subcounties surveyed within and outside Mukono district. -

Human Rights Violations

dysfunctional nature of the system they inherited and maintained. Ad- mittedly, theirs is a peculiar "au- tonomous"behaviour which contrib- utes to gross violations of rights and the socio-economic and political de- cay of the state. Another factor that sustains the culture of crises is ex- ternal to the country. Firstly, a HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS number of governments, democratic and authoritarian, in the South and North, have directly and indirectly supported dictatorial regimes in the country. Through economic, diplo- matic and military assistance the wheel ofviolence and dictatorship is serviced. Secondly, by treating the crises as essentially internal affairs In the past three decades since sequence off tends to change other of the sovereign state, the interna- Uganda gained independence from qualities of life so that from a number tional community has done little to Britain, the country has experienced of different starting points, follow- avert violations of rights. Finally, some of the worst human catastro- ing different trajectories of change, by maintaining the unjust and ex- phes in modern times -gross viola- comparable results may ensue. This ploitative international economic tions of human rights, amounting to view seems to hold true for all the system which violates the right to genocide and generating millions of questions posited. Nonetheless, on development, the international com- refugees and internally displaced the balance of the evidence, this munity directly violates the rights persons; state sponsored terrorism, paper contends that while the ori- of Ugandans. dictatorship, nepotism, corruption, gins of violations of rights in Uganda The point is, the economic under- ethnicity, civil wars, famine; total lie in a blend of factors, colonialism development of the country, which collapse of the economy; the disinte- and its lopsided socio-economic and is a result of both internal and ex- gration and demise of the state. -

Chased Away and Left to Die

Chased Away and Left to Die How a National Security Approach to Uganda’s National Digital ID Has Led to Wholesale Exclusion of Women and Older Persons ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Publication date: June 8, 2021 Cover photo taken by ISER. An elderly woman having her biometric and biographic details captured by Centenary Bank at a distribution point for the Senior Citizens’ Grant in Kayunga District. Consent was obtained to use this image in our report, advocacy, and associated communications material. Copyright © 2021 by the Center for Human Rights and Global Justice, Initiative for Social and Economic Rights, and Unwanted Witness. All rights reserved. Center for Human Rights and Global Justice New York University School of Law Wilf Hall, 139 MacDougal Street New York, New York 10012 United States of America This report does not necessarily reflect the views of NYU School of Law. Initiative for Social and Economic Rights Plot 60 Valley Drive, Ministers Village Ntinda – Kampala Post Box: 73646, Kampala, Uganda Unwanted Witness Plot 41, Gaddafi Road Opp Law Development Centre Clock Tower Post Box: 71314, Kampala, Uganda 2 Chased Away and Left to Die ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report is a joint publication by the Digital Welfare State and Human Rights Project at the Center for Human Rights and Global Justice (CHRGJ) based at NYU School of Law in New York City, United States of America, the Initiative for Social and Economic Rights (ISER) and Unwanted Witness (UW), both based in Kampala, Uganda. The report is based on joint research undertaken between November 2020 and May 2021. Work on the report was made possible thanks to support from Omidyar Network and the Open Society Foundations. -

THE UGANDA GAZETTE [13Th J Anuary

The THE RH Ptrat.ir OK I'<1 AND A T IE RKPt'BI.IC OF UGANDA Registered at the Published General Post Office for transmission within by East Africa as a Newspaper Uganda Gazette A uthority Vol. CX No. 2 13th January, 2017 Price: Shs. 5,000 CONTEXTS P a g e General Notice No. 12 of 2017. The Marriage Act—Notice ... ... ... 9 THE ADVOCATES ACT, CAP. 267. The Advocates Act—Notices ... ... ... 9 The Companies Act—Notices................. ... 9-10 NOTICE OF APPLICATION FOR A CERTIFICATE The Electricity Act— Notices ... ... ... 10-11 OF ELIGIBILITY. The Trademarks Act—Registration of Applications 11-18 Advertisements ... ... ... ... 18-27 I t is h e r e b y n o t if ie d that an application has been presented to the Law Council by Okiring Mark who is SUPPLEMENTS Statutory Instruments stated to be a holder of a Bachelor of Laws Degree from Uganda Christian University, Mukono, having been No. 1—The Trade (Licensing) (Grading of Business Areas) Instrument, 2017. awarded on the 4th day of July, 2014 and a Diploma in No. 2—The Trade (Licensing) (Amendment of Schedule) Legal Practice awarded by the Law Development Centre Instrument, 2017. on the 29th day of April, 2016, for the issuance of a B ill Certificate of Eligibility for entry of his name on the Roll of Advocates for Uganda. No. 1—The Anti - Terrorism (Amendment) Bill, 2017. Kampala, MARGARET APINY, 11th January, 2017. Secretary, Law Council. General N otice No. 10 of 2017. THE MARRIAGE ACT [Cap. 251 Revised Edition, 2000] General Notice No. -

Population by Parish

Total Population by Sex, Total Number of Households and proportion of Households headed by Females by Subcounty and Parish, Central Region, 2014 District Population Households % of Female Males Females Total Households Headed HHS Sub-County Parish Central Region 4,672,658 4,856,580 9,529,238 2,298,942 27.5 Kalangala 31,349 22,944 54,293 20,041 22.7 Bujumba Sub County 6,743 4,813 11,556 4,453 19.3 Bujumba 1,096 874 1,970 592 19.1 Bunyama 1,428 944 2,372 962 16.2 Bwendero 2,214 1,627 3,841 1,586 19.0 Mulabana 2,005 1,368 3,373 1,313 21.9 Kalangala Town Council 2,623 2,357 4,980 1,604 29.4 Kalangala A 680 590 1,270 385 35.8 Kalangala B 1,943 1,767 3,710 1,219 27.4 Mugoye Sub County 6,777 5,447 12,224 3,811 23.9 Bbeta 3,246 2,585 5,831 1,909 24.9 Kagulube 1,772 1,392 3,164 1,003 23.3 Kayunga 1,759 1,470 3,229 899 22.6 Bubeke Sub County 3,023 2,110 5,133 2,036 26.7 Bubeke 2,275 1,554 3,829 1,518 28.0 Jaana 748 556 1,304 518 23.0 Bufumira Sub County 6,019 4,273 10,292 3,967 22.8 Bufumira 2,177 1,404 3,581 1,373 21.4 Lulamba 3,842 2,869 6,711 2,594 23.5 Kyamuswa Sub County 2,733 1,998 4,731 1,820 20.3 Buwanga 1,226 865 2,091 770 19.5 Buzingo 1,507 1,133 2,640 1,050 20.9 Maziga Sub County 3,431 1,946 5,377 2,350 20.8 Buggala 2,190 1,228 3,418 1,484 21.4 Butulume 1,241 718 1,959 866 19.9 Kampala District 712,762 794,318 1,507,080 414,406 30.3 Central Division 37,435 37,733 75,168 23,142 32.7 Bukesa 4,326 4,711 9,037 2,809 37.0 Civic Centre 224 151 375 161 14.9 Industrial Area 383 262 645 259 13.9 Kagugube 2,983 3,246 6,229 2,608 42.7 Kamwokya -

Margaret Sekaggya P.O

MARGARET SEKAGGYA P.O. Box 3176, Kampala, Uganda. Tel. No: 256-414-348007/8/10/14 Residence Telephone No: 256-414-270160 Mobile No: 256-772-788821 Fax No: 256-414-255261 E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] CURRICULUM VITAE Date of Birth: Kampala 23rd October 1949 Status: Married PROFESSIONAL QUALIFICATIONS 1990 University of Zambia, Lusaka. Master of Laws (LL.M) Degree. Subjects: Constitutional Law, Comparative Family Law, International Law and Jurisprudence. Dissertation in the area of Evidence entitled “The Law of Corroboration with Special reference to Zambia”. 1970-1973: Makerere University, Kampala. Bachelor of Laws (LLB.) Hons. Degree (Did 12 law courses) 1973-74: Law Development Centre, Makerere Post-Graduate Diploma in Legal Practice (Dip. L.P). 1975: All African Law Reports, Oxford U.K. Course in Law Reporting- prepared in producing law reports. 1977: High Court of Uganda, Kampala. Enrolled Advocate of the High Court of Uganda. 1997: Danish Centre for Human Rights, Human Rights Course – Trained in the International Instruments. 1998: The Commonwealth Secretariat, Kampala Uganda. Training in Human Rights 1 PROFESSIONAL SUMMARY A lawyer of longstanding who has worked with the Governments of Uganda, Zambia and also with the United Nations. Taught law in various institutions, worked in the Judiciary and finally appointed a Judge of the High Court of Uganda. Administrative experience acquired through setting up of the Uganda Human Rights Commission, which is one of the strongest Commissions in Africa and has a staff of 153 members. Represented the Commission at both local and International fora, including the annual representation at the United Nations Human Rights Sessions in Geneva.