Cinderella Stories and the Construction of Gender

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(87Ef42f) Pdf Just Ella (Aladdin Fantasy) (The Palace

pdf Just Ella (Aladdin Fantasy) (The Palace Chronicles) Margaret Peterson Haddix, Ren - pdf free book read online free Just Ella (Aladdin Fantasy) (The Palace Chronicles), Read Online Just Ella (Aladdin Fantasy) (The Palace Chronicles) E-Books, Read Online Just Ella (Aladdin Fantasy) (The Palace Chronicles) E-Books, the book Just Ella (Aladdin Fantasy) (The Palace Chronicles), Read Best Book Just Ella (Aladdin Fantasy) (The Palace Chronicles) Online, Just Ella (Aladdin Fantasy) (The Palace Chronicles) Free Download, read online free Just Ella (Aladdin Fantasy) (The Palace Chronicles), Just Ella (Aladdin Fantasy) (The Palace Chronicles) Full Collection, Read Best Book Online Just Ella (Aladdin Fantasy) (The Palace Chronicles), Read Best Book Just Ella (Aladdin Fantasy) (The Palace Chronicles) Online, Just Ella (Aladdin Fantasy) (The Palace Chronicles) PDF read online, I Was So Mad Just Ella (Aladdin Fantasy) (The Palace Chronicles) Margaret Peterson Haddix, Ren Ebook Download, Read Just Ella (Aladdin Fantasy) (The Palace Chronicles) Books Online Free, Download Just Ella (Aladdin Fantasy) (The Palace Chronicles) E-Books, Read Just Ella (Aladdin Fantasy) (The Palace Chronicles) Online Free, PDF Download Just Ella (Aladdin Fantasy) (The Palace Chronicles) Free Collection, Just Ella (Aladdin Fantasy) (The Palace Chronicles) PDF Download, Just Ella (Aladdin Fantasy) (The Palace Chronicles) Margaret Peterson Haddix, Ren pdf, Just Ella (Aladdin Fantasy) (The Palace Chronicles) Free Download, Free Download Just Ella (Aladdin Fantasy) (The Palace Chronicles) Full Popular Margaret Peterson Haddix, Ren, CLICK HERE - DOWNLOAD mobi, kindle, pdf, epub Description: The term'male' means an extremely narrow spectrum of male characters men are usually more aggressive in their behaviour and they seem less likely than females. -

Accelerated Reader Book List

Accelerated Reader Book List Picking a book to read? Check the Accelerated Reader quiz list below and choose a book that will count for credit in grade 7 or grade 8 at Quabbin Middle School. Please see your teacher if you have questions about any selection. The most recently added books/tests are denoted by the darkest blue background as shown here. Book Quiz No. Title Author Points Level 8451 EN 100 Questions and Answers About AIDS Ford, Michael Thomas 7.0 8.0 101453 EN 13 Little Blue Envelopes Johnson, Maureen 5.0 9.0 5976 EN 1984 Orwell, George 8.2 16.0 9201 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Clare, Andrea M. 4.3 2.0 523 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Unabridged) Verne, Jules 10.0 28.0 6651 EN 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila Sprague 4.1 2.0 593 EN 25 Cent Miracle, The Nelson, Theresa 7.1 8.0 59347 EN 5 Ways to Know About You Gravelle, Karen 8.3 5.0 8851 EN A.B.C. Murders, The Christie, Agatha 7.6 12.0 81642 EN Abduction! Kehret, Peg 4.7 6.0 6030 EN Abduction, The Newth, Mette 6.8 9.0 101 EN Abel's Island Steig, William 6.2 3.0 65575 EN Abhorsen Nix, Garth 6.6 16.0 11577 EN Absolutely Normal Chaos Creech, Sharon 4.7 7.0 5251 EN Acceptable Time, An L'Engle, Madeleine 7.5 15.0 5252 EN Ace Hits the Big Time Murphy, Barbara 5.1 6.0 5253 EN Acorn People, The Jones, Ron 7.0 2.0 8452 EN Across America on an Emigrant Train Murphy, Jim 7.5 4.0 102 EN Across Five Aprils Hunt, Irene 8.9 11.0 6901 EN Across the Grain Ferris, Jean 7.4 8.0 Across the Wide and Lonesome Prairie: The Oregon 17602 EN Gregory, Kristiana 5.5 4.0 Trail Diary.. -

古典及現代灰姑娘故事中的女性角色 Looking Into the Female Characters in Cinderella Fairy Tales Then and Now by HU

古典及現代灰姑娘故事中的女性角色 Looking into the Female Characters in Cinderella Fairy Tales Then and Now by HUI-CHIH CHAN 詹惠芝 THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the Department of Foreign Languages and Literature of Tunghai University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in British and American Literature TUNGHAI UNIVERSITY June 2019 中 華 民 國 一0八年 六 月 古典及現代灰姑娘故事中的女性角色 Looking into the Female Characters in Cinderella Fairy Tales Then and Now by HUI-CHIH CHAN 詹惠芝 THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the Department of Foreign Languages and Literature of Tunghai University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in British and American Literature TUNGHAI UNIVERSITY June 2019 中 華 民 國 一0八年 六 月 Acknowledgements Years ago, I was very lucky to have the opportunity to study English literature at the Foreign Languages and Literature (FLL) Department of Tunghai University as a middle-aged student, coming back to college after a long break from school. As I look back on this long journey, I am so grateful to each and every administrator, staff, and particularly faculty members at this department who have helped me with my undergraduate and graduate studies. I am especially thankful to Dr. Mieke Desmet, who has taught me to appreciate children’s literature and has always been willing to take time out of her busy schedule to supervise me on my thesis. I simply cannot thank her enough for her patience to guide me to the end of my graduate program. I would also like to thank my English tutor, Mr. -

Roberts, Nora

Marillier, Juliet Showalter, Gena TEENS Wildwood Dancing White Rabbit Chronicles (Twelve Dancing Princesses) (Alice in Wonderland) If You Enjoyed Five sisters who live with their merchant father To avenge the death of her parents and sister in Transylvania use a hidden portal in their Ali must learn to fight the undead, and to Reading home to cross over into a magical world, the survive she must learn to trust the baddest of Wildwood. the bad boys, Cole Holland. But Cole has his own secrets, which might just prove to be more McKinley, Robin dangerous than the zombies. Beauty (Beauty and the Best) A classic retelling of Beauty and the Beast. Stanley, Diane Bella at Midnight (Cinderella) Meyer, Marissa Raised by peasants, Bella discovers that she is Lunar Chronicles (series) actually the daughter of a knight and finds (Cinderella, Little Red Riding Hood, Rapunzel) herself caught up in a plot that will change her A futuristic retelling of classic fairy tales forever. involving a cyborg and an evil queen. Wrede, Patricia Napoli, Donna Jo Dealing with Dragons Bound (Cinderella) (available to download) In a novel based on Chinese Cinderella tales, (Miscellaneous Fairy Tales) fourteen-year-old stepchild Xing-Xing endures A princess goes off to live with a group of a life of neglect and servitude, as her dragons and soon becomes involved with stepmother cruelly mutilates her own child's fighting against wizards who want to steal the feet so that she alone might marry well. dragons' kingdom. Pearce, Jackson Wrede, Patricia Alice in Zombieland by Gena Showalter Sisters Red (Little Red Riding Hood) Snow White and Rose Red Cinder by Marissa Meyer (Snow White and the Seven Dwarves) After a werewolf kills their grandmother, sisters Scarlett and Rosie March devote themselves to Elizabethan English tricksters John Dee and killing the beasts that prey on teenaged girls. -

Quiz List—Reading Practice Page 1 Printed Tuesday, February 12, 2013 12:12:12 PM School: Woodland Middle School

Quiz List—Reading Practice Page 1 Printed Tuesday, February 12, 2013 12:12:12 PM School: Woodland Middle School Reading Practice Quizzes Quiz Word Number Lang. Title Author IL ATOS BL Points Count F/NF 144408 EN 13 Curses Harrison, Michelle MG 5.3 16.0 107,383 F 136675 EN 13 Treasures Harrison, Michelle MG 5.3 11.0 73,953 F 8251 EN 18-Wheelers Maifair, Linda Lee MG 5.2 1.0 5,229 NF 9801 EN 1980 U.S. Hockey Team Coffey, Wayne MG 6.4 1.0 6,130 NF 5976 EN 1984 Orwell, George UG 8.9 17.0 88,942 F 523 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Verne, Jules MG 10.0 28.0 138,138 F (Unabridged) 11592 EN 2095 Scieszka, Jon MG 3.8 1.0 10,043 F 6651 EN 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila Sprague MG 3.3 1.0 10,339 F 593 EN 25 Cent Miracle, The Nelson, Theresa MG 5.6 7.0 43,360 F 1302 EN 3 NBs of Julian Drew, The Deem*, James M. U 3.6 5.0 38,042 F 128675 EN 3 Willows: The Sisterhood Grows Brashares, Ann MG 4.5 9.0 63,547 F 8252 EN 4X4's and Pickups Donahue, A.K. MG 4.2 1.0 5,130 NF 901 EN Abduction Kehret*, Peg U 4.7 6.0 39,470 F 6030 EN Abduction, The Newth, Mette UG 6.0 8.0 50,015 F 101 EN Abel's Island Steig, William MG 5.9 3.0 17,610 F 65575 EN Abhorsen Nix, Garth UG 6.6 16.0 99,206 F 14931 EN Abominable Snowman of Stine, R.L. -

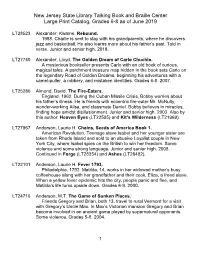

Large Print Catalog — Grades 6 to 8

New Jersey State Library Talking Book and Braille Center Large Print Catalog, Grades 6-8 as of June 2019 LT28523 Alexander, Kwame. Rebound. 1988. Charlie is sent to stay with his grandparents, where he discovers jazz and basketball. He also learns more about his father’s past. Told in verse. Junior and senior high. 2018. LT27740 Alexander, Lloyd. The Golden Dream of Carlo Chuchio. A mysterious bookseller presents Carlo with an old book of curious, magical tales. A parchment treasure map hidden in the book sets Carlo on the legendary Road of Golden Dreams, beginning his adventures with a camel-puller, a robbery, and mistaken identities. Grades 6-8. 2007. LT25280 Almond, David. The Fire-Eaters. England, 1962. During the Cuban Missile Crisis, Bobby worries about his father’s illness. He is friends with eccentric fire-eater Mr. McNulty, wonder-working Ailsa, and classmate Daniel. Bobby believes in miracles, finding hope amidst disillusionment. Junior and senior high. 2003. Also by this author: Heaven Eyes (LT22595) and Kit’s Wilderness (LT21969). LT27967 Anderson, Laurie H. Chains, Seeds of America Book 1. American Revolution. Teenage slave Isabel and her younger sister are taken from Rhode Island and sold to an abusive Loyalist couple in New York City, where Isabel spies on the British to win her freedom. Some violence and some strong language. Junior and senior high. 2008. Continued in Forge (LT28354) and Ashes (LT28482). LT22101 Anderson, Laurie H. Fever 1793. Philadelphia, 1793. Matilda, 14, works in her widowed mother’s busy coffeehouse along with her grandfather and their cook, Eliza, a freed slave. -

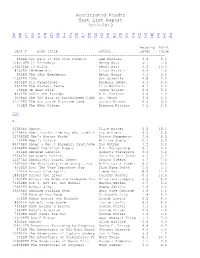

Reading Practice Quiz List Report Page 1 Accelerated Reader®: Friday, 03/04/11, 08:41 AM

Reading Practice Quiz List Report Page 1 Accelerated Reader®: Friday, 03/04/11, 08:41 AM Lakes Middle School Reading Practice Quizzes Int. Book Point Fiction/ Quiz No. Title Author Level Level Value Language Nonfiction 17351 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro BaseballBob Italia MG 5.5 1.0 English Nonfiction 17352 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro BasketballBob Italia MG 6.5 1.0 English Nonfiction 17353 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro FootballBob Italia MG 6.2 1.0 English Nonfiction 17354 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro GolfBob Italia MG 5.6 1.0 English Nonfiction 17355 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro HockeyBob Italia MG 6.1 1.0 English Nonfiction 17356 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro TennisBob Italia MG 6.4 1.0 English Nonfiction 17357 100 Unforgettable Moments in SummerBob Olympics Italia MG 6.5 1.0 English Nonfiction 17358 100 Unforgettable Moments in Winter OlympicsBob Italia MG 6.1 1.0 English Nonfiction 18751 101 Ways to Bug Your Parents Lee Wardlaw MG 3.9 5.0 English Fiction 11101 A 16th Century Mosque Fiona MacDonald MG 7.7 1.0 English Nonfiction 8251 18-Wheelers Linda Lee Maifair MG 5.2 1.0 English Nonfiction 661 The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars MG 4.7 4.0 English Fiction 9801 1980 U.S. Hockey Team Wayne Coffey MG 6.4 1.0 English Nonfiction 523 20,000 Leagues under the Sea Jules Verne MG 10.0 28.0 English Fiction 9201 20,000 Leagues under the Sea (Pacemaker)Verne/Clare UG 4.3 2.0 English Fiction 34791 2001: A Space Odyssey Arthur C. -

Young Adult Female Protagonists Book List Denotes New Titles Recently Added to the List

Young Adult Female Protagonists Book List Denotes new titles recently added to the list Abdel-Fattah, Randa O'Connell's journey to America after their Does My Head Look Big In parents' cottage is destroyed by their greedy This? landlord. Their paths intersect with that of Year Eleven at an exclusive prep Laurence Kirkle, who is also running away to school in the suburbs of the land of opportunity. Melbourne, Australia, would be tough enough, but it is further complicated Bauer, Joan for Amal when she decides to wear the hijab, Hope Was Here the Muslim head scarf, full-time as a badge of Sixteen-year-old Hope takes her faith--without losing her identity or sense pride in her job: she's a short- of style. (Summary from Destiny Follett, Oct order waitress who has come 2009) from Brooklyn with her aunt Addie to run a diner in Wisconsin, its proprietor sidelined by Amateau, Gigi leukemia. Addie and Hope, long peripatetic, A Certain Strain of Peculiar find a new life in Wisconsin as well as a cause: Tired of the miserable life she the diner's owner takes on the corrupt mayor lives, Mary Harold leaves her in an upcoming election. And Hope's mother behind and moves back tentative romance with the cook is sweet to Alabama and her indeed. grandmother, where she receives support and love and starts to gain confidence in herself Bauer, Joan and her abilities. The Rules of the Road Jenna, newly armed with a Anderson, Laurie Halse driver's license, thought she had Chains her summer all worked out--until After being sold to a cruel couple Mrs. -

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

Accelerated Reader Test List Report 2012-2013 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Reading Point Test # Book Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 922EN 101 Ways to Bug Your Parents Lee Wardlaw 3.9 5.0 128370EN 11 Birthdays Wendy Mass 4.1 7.0 146272EN 13 Gifts Wendy Mass 4.5 13.0 8251EN 18-Wheelers Linda Maifair 4.4 1.0 661EN The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars 4.1 3.0 11592EN 2095 Jon Scieszka 4.8 2.0 6201EN 213 Valentines Barbara Cohen 3.1 2.0 6651EN The 24-Hour Genie Lila McGinnis 4.1 2.0 166EN 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson 5.2 5.0 8252EN 4X4's and Pickups A.K. Donahue 4.5 1.0 9001EN The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubb Dr. Seuss 3.9 1.0 31170EN The 6th Grade Nickname Game Gordon Korman 4.3 3.0 413EN The 89th Kitten Eleanor Nilsson 4.3 2.0 TOP A 64593EN Abarat Clive Barker 5.5 15.0 61248EN Abe Lincoln: The Boy Who Loved B Kay Winters 3.6 0.5 127685EN Abe's Honest Words Doreen Rappaport 4.9 0.5 101EN Abel's Island William Steig 6.2 3.0 86479EN Abner & Me: A Baseball Card Adve Dan Gutman 4.2 5.0 54088EN About the B'nai Bagels E.L. Konigsburg 4.7 5.0 815EN Abraham Lincoln Augusta Stevenson 3.2 3.0 29341EN Abraham's Battle Sara Harrell Banks 5.3 2.0 11577EN Absolutely Normal Chaos Sharon Creech 4.7 7.0 12573EN The Absolutely True Story...How Willo Davis Robert 5.1 6.0 6001EN Ace: The Very Important Pig Dick King-Smith 5.0 3.0 102EN Across Five Aprils Irene Hunt 8.9 11.0 18801EN Across the Lines Carolyn Reeder 6.3 10.0 17602EN Across the Wide and Lonesome Pra Kristiana Gregory -

Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books

ILLINI S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. ·, , I university ot minois Graduate School of Library and Information Science University of Illinois Press i I· iiS: r 01 "· i"' Kirkus Reviews and School Library Journal star ONE LIGHTHOUSE, ONE MOON by ANITA LOBEL V ' "Beautiful paintings are the heart of this concept book divided into three 'chapters' The first shows a different pair of shoes in a different color for each day of the week. The middle section introduces the months of the year via the antics of a cat named Nini. The final section is a seaside counting exercise from 'ONE lighthouse' to'TEN trees bent back in the wind. And ONE HUNDRED stars and ONE moon lit up in the sky' This fresh approach to the concepts covered has great visual appeal." -Starred review/School LibraryJournal ^ '"A perfect concept book" -Starred review/Kirkus Reviews Ages 4 up. $15.95 Tr (0-688-15539-1) $15.89 Lb (0-688-15540-5) THE BULLETIN OF THE CENTER FOR CHILDREN'S BOOKS July/August 2000 Vol. 53 No. 11 A LOOK INSIDE 387 THE BIG PICTURE So You Want to Be President? by Judith St. George; illus. by David Small 388 NEW BOOKS FOR CHILDREN AND YOUNG PEOPLE Reviewed titles include: 388 * Sir Walter Ralegh and the Questfor El Dorado by Marc Aronson 392 * Uncommon Traveler: Mary Kingsley in Africa written and illus. by Don Brown 406 * Days Like This: A Collection ofSmall Poems comp. and illus. -

The Cinderella Chronicles the Cinderella Chronicles

THE CINDERELLA CHRONICLES __________________________ A one-act comedy by Susan M. Steadman This script is for evaluation only. It may not be printed, photocopied or distributed digitally under any circumstances. Possession of this file does not grant the right to perform this play or any portion of it, or to use it for classroom study. www.youthplays.com [email protected] 424-703-5315 The Cinderella Chronicles © 2010 Susan M. Steadman All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-62088-429-4. Caution: This play is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, Canada, the British Commonwealth and all other countries of the copyright union and is subject to royalty for all performances including but not limited to professional, amateur, charity and classroom whether admission is charged or presented free of charge. Reservation of Rights: This play is the property of the author and all rights for its use are strictly reserved and must be licensed by his representative, YouthPLAYS. This prohibition of unauthorized professional and amateur stage presentations extends also to motion pictures, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video and the rights of adaptation or translation into non-English languages. Performance Licensing and Royalty Payments: Amateur and stock performance rights are administered exclusively by YouthPLAYS. No amateur, stock or educational theatre groups or individuals may perform this play without securing authorization and royalty arrangements in advance from YouthPLAYS. Required royalty fees for performing this play are available online at www.YouthPLAYS.com. Royalty fees are subject to change without notice. Required royalties must be paid each time this play is performed and may not be transferred to any other performance entity. -

Accelerated Reader Book List

Accelerated Reader Book List Book Title Author Reading Level Point Value ---------------------------------- -------------------- ------- ------ 12 Again Sue Corbett 4.9 8 13: Thirteen Stories...Agony and James Howe 5 9 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Catherine O'Neill 7.1 1 1906 San Francisco Earthquake Tim Cooke 6.1 1 1984 George Orwell 8.9 17 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Un Jules Verne 10 28 2010: Odyssey Two Arthur C. Clarke 7.8 13 3 NBs of Julian Drew James M. Deem 3.6 5 3001: The Final Odyssey Arthur C. Clarke 8.3 9 47 Walter Mosley 5.3 8 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson 4.6 4 The A.B.C. Murders Agatha Christie 6.1 9 Abandoned Puppy Emily Costello 4.1 3 Abarat Clive Barker 5.5 15 Abduction! Peg Kehret 4.7 6 The Abduction Mette Newth 6 8 Abel's Island William Steig 5.9 3 The Abernathy Boys L.J. Hunt 5.3 6 Abhorsen Garth Nix 6.6 16 Abigail Adams: A Revolutionary W Jacqueline Ching 8.1 2 About Face June Rae Wood 4.6 9 Above the Veil Garth Nix 5.3 7 Abraham Lincoln: Friend of the P Clara Ingram Judso 7.3 7 N Abraham Lincoln: From Pioneer to E.B. Phillips 8 4 N Absolute Brightness James Lecesne 6.5 15 Absolutely Normal Chaos Sharon Creech 4.7 7 N The Absolutely True Diary of a P Sherman Alexie 4 6 N An Abundance of Katherines John Green 5.6 10 Acceleration Graham McNamee 4.4 7 An Acceptable Time Madeleine L'Engle 4.5 11 N Accidental Love Gary Soto 4.8 5 Ace Hits the Big Time Barbara Murphy 4.2 6 Ace: The Very Important Pig Dick King-Smith 5.2 3 Achingly Alice Phyllis Reynolds N 4.9 4 The Acorn People Ron Jones 5.6 2 Acorna: The Unicorn Girl