Creating the First Ulster Plantation Town

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irish Historic Towns Atlas (IHTA), No. 20, Tuam Author

Digital content from: Irish Historic Towns Atlas (IHTA), no. 20, Tuam Author: J.A. Claffey Editors: Anngret Simms, H.B. Clarke, Raymond Gillespie, Jacinta Prunty Consultant editor: J.H. Andrews Cartographic editor: Sarah Gearty Editorial assistants: Angela Murphy, Angela Byrne, Jennnifer Moore Printed and published in 2009 by the Royal Irish Academy, 19 Dawson Street, Dublin 2 Maps prepared in association with the Ordnance Survey Ireland and Land and Property Services Northern Ireland The contents of this digital edition of Irish Historic Towns Atlas no. 20, Tuam, is registered under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International License. Referencing the digital edition Please ensure that you acknowledge this resource, crediting this pdf following this example: Topographical information. In J.A. Claffey, Irish Historic Towns Atlas, no. 20, Tuam. Royal Irish Academy, Dublin, 2009 (www.ihta.ie, accessed 4 February 2016), text, pp 1–20. Acknowledgements (digital edition) Digitisation: Eneclann Ltd Digital editor: Anne Rosenbusch Original copyright: Royal Irish Academy Irish Historic Towns Atlas Digital Working Group: Sarah Gearty, Keith Lilley, Jennifer Moore, Rachel Murphy, Paul Walsh, Jacinta Prunty Digital Repository of Ireland: Rebecca Grant Royal Irish Academy IT Department: Wayne Aherne, Derek Cosgrave For further information, please visit www.ihta.ie TUAM View of R.C. cathedral, looking west, 1843 (Hall, iii, p. 413) TUAM Tuam is situated on the carboniferous limestone plain of north Galway, a the turbulent Viking Age8 and lends credence to the local tradition that ‘the westward extension of the central plain. It takes its name from a Bronze Age Danes’ plundered Tuam.9 Although the well has disappeared, the site is partly burial mound originally known as Tuaim dá Gualann. -

A Fractious and Naughty People: the Border Reivers in Ireland

A Fractious and Naughty People: The Border Reivers in Ireland By Trevor Graham King James the Sixth faced a serious problem in 1604. He had just become the King of England the previous year, in addition to already being the King of Scotland. He had recently ordered the border between Scotland and England pacified of the “Border Reivers”, warlike families whose activities of raiding and pillaging had been encouraged (and in some cases, funded) by the Scottish and English governments during times of war. Armies were hard to maintain, but entire families of marauders were cost effective and deadly. But now, with the countries united under a single monarch and supposed to be working together, their wanton destruction was no longer tolerated and was swiftly punished by the English and Scottish March Wardens with “Jeddart justice” (summary execution). He couldn’t hang all those responsible, so James decided to relocate the troublesome families. Recently, rebellious earls in Ireland had fled the country, and plans were set up to settle that land with loyal Protestants from Great Britain. But there were not enough settlers, and many native Irish still lived on that land in the northern part known as Ulster. Hoping to solve both problems at once, James and his government sent many Border families to the plantations around Ireland. Instead of being productive and keeping the peace however, they instead caused a sectarian split within Ireland. This led to nearly 400 years of bloodshed, leaving a scar that has remained to this day in Northern Ireland. To find out how all this fury and bloodshed began, we go back to 1601, when the combined forces of Hugh O’Neil, Hugh O’Donnell, and a Spanish force were defeated by the English at Kinsale. -

Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland

COLONEL- MALCOLM- OF POLTALLOCH CAMPBELL COLLECTION Rioghachca emeaNN. ANNALS OF THE KINGDOM OF IEELAND, BY THE FOUR MASTERS, KKOM THE EARLIEST PERIOD TO THE YEAR 1616. EDITED FROM MSS. IN THE LIBRARY OF THE ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY AND OF TRINITY COLLEGE, DUBLIN, WITH A TRANSLATION, AND COPIOUS NOTES, BY JOHN O'DONOYAN, LLD., M.R.I.A., BARRISTER AT LAW. " Olim Regibus parebaut, nuuc per Principes faction! bus et studiis trahuntur: nee aliud ad versus validiasiuias gentes pro uobis utilius, qnam quod in commune non consulunt. Rarus duabus tribusve civitatibus ad propulsandum eommuu periculom conventus : ita dum singnli pugnant umVersi vincuntur." TACITUS, AQBICOLA, c. 12. SECOND EDITION. VOL. VII. DUBLIN: HODGES, SMITH, AND CO., GRAFTON-STREET, BOOKSELLERS TO THE UNIVERSITY. 1856. DUBLIN : i3tintcc at tije ffinibcrsitn )J\tss, BY M. H. GILL. INDEX LOCORUM. of the is the letters A. M. are no letter is the of Christ N. B. When the year World intended, prefixed ; when prefixed, year in is the Irish form the in is the or is intended. The first name, Roman letters, original ; second, Italics, English, anglicised form. ABHA, 1150. Achadh-bo, burned, 1069, 1116. Abhaill-Chethearnaigh, 1133. plundered, 913. Abhainn-da-loilgheach, 1598. successors of Cainneach of, 969, 1003, Abhainn-Innsi-na-subh, 1158. 1007, 1008, 1011, 1012, 1038, 1050, 1066, Abhainn-na-hEoghanacha, 1502. 1108, 1154. Abhainn-mhor, Owenmore, river in the county Achadh-Chonaire, Aclionry, 1328, 1398, 1409, of Sligo, 1597. 1434. Abhainn-mhor, The Blackwater, river in Mun- Achadh-Cille-moire,.4^az7wre, in East Brefny, ster, 1578, 1595. 1429. Abhainn-mhor, river in Ulster, 1483, 1505, Achadh-cinn, abbot of, 554. -

The Influence of the Irish Tudor and Stuart Plantation Experiences in the Evolution of American Colonial Theory and Practice

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1992 "This Famous Island in the Virginia Sea": The Influence of the Irish Tudor and Stuart Plantation Experiences in the Evolution of American Colonial Theory and Practice Meaghan Noelle Duff College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Duff, Meaghan Noelle, ""This Famous Island in the Virginia Sea": The Influence of the Irish udorT and Stuart Plantation Experiences in the Evolution of American Colonial Theory and Practice" (1992). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625771. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-kvrp-3b47 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "THIS FAMOUS ISLAND IN THE VIRGINIA SEA": THE INFLUENCE OF IRISH TUDOR AND STUART PLANTATION EXPERIENCES ON THE EVOLUTION OF AMERICAN COLONIAL THEORY AND PRACTICE A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY IN VIRGINIA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY MEAGHAN N. DUFF MAY, 1992 APPROVAL SHEET THIS THESIS IS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS AGHAN N APPROVED, MAY 1992 '''7 ^ ^ THADDEUS W. TATE A m iJI________ JAMES AXTELL CHANDOS M. -

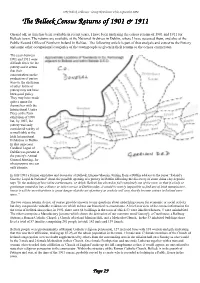

The Belleek Census Returns of 1901 & 1911 the Belleek Census

UK Belleek Collectors’ Group Newsletter 25/2, September 2004 The Belleek Census Returns of 1901 & 1911 On and off, as time has been available in recent years, I have been analysing the census returns of 1901 and 1911 for Belleek town. The returns are available at the National Archives in Dublin, where I have accessed them, and also at the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland in Belfast. The following article is part of that analysis and concerns the Pottery and some other occupational categories of the townspeople as given in their returns to the census enumerator. The years between 1901 and 1911 were difficult times for the pottery and it seems that their concentration on the production of parian ware to the exclusion of other forms of pottery may not have been good policy. They may have made quite a name for themselves with the International Centre Piece at the Paris exhibition of 1900 but, by 1907, the pottery was only considered worthy of a small table at the Irish International Exhibition in Dublin. In that same year Cardinal Logue of Dublin was present at the pottery's Annual General Meeting, for what purpose one can only surmise. In July 1901 a former employee and decorator at Belleek, Eugene Sheerin, writing from a Dublin address to the paper "lreland's Gazette, Loyal & National" about the possible opening of a pottery in Dublin following the discovery of some china clay deposits says "In the making of best white earthenware, or delph, Belleek has elected to fall completely out of the race; so that if a lady or gentleman wanted to buy a dinner or toilet service in Dublin today, it would be utterly impossible to find one of Irish manufacture, hence it will be seen that there is great danger that the art of pottery as a whole will very shortly become extinct in Ireland once more." The two census returns do not, of course, provide answers to any questions about underlying causes for economic or social activity but they can provide valuable evidence on which to base our historical re-enactments. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Dr. Éamonn Ó Ciardha Senior Lecturer School of English, History and Politics Room MI208 Aberfoyle House Magee Campus University of Ulster Northland Road Derry/Londonderry BT 48 7JL Tel.: 02871-375257 E.Mail: [email protected] Education: Ph.D., 1992-98 (Clare Hall, Cambridge University). 'A Fatal Attachment: Ireland and the Jacobite cause 1684-1766'. Supervisor: Dr. B. I. Bradshaw [Queens' College Cambridge] M.A., 1989-91 (University College Dublin). “Buachaillí an tsléibhe agus bodaigh gan chéille” [‘Mountain boys and senseless churls’], Woodkerne, Tories and Rapparees in Ulster and North Connaught in the Seventeenth Century'. Supervisor: J.I. Mc Guire B.A., 1986-89 (University College Dublin). History and Irish Appointments: Lecturer, School of English, History and Politics, University of Ulster (Oct 2005-) Program Coordinator and Director of Undergraduate Studies, Keough Institute for Irish Studies, University of Notre Dame, Indiana, USA, (Aug 2004-Jun 2005) IRCHSS (Government of Ireland) Post-Doctoral Fellow, Department of Modern History, Trinity College Dublin. (Oct 2002-Oct 2004) Visiting Adjunct Professor, Keough Institute of Irish Studies, University of Notre Dame and Assistant Professional Specialist in University Libraries, University of Notre Dame (Aug, 2001-Jul 2002) Visiting Professor of Irish Studies, St. Michael’s College, University of Toronto. (Sept, 2000-Dec 2000) Researcher for the Royal Irish Academy-sponsored Dictionary of Irish Biography (Nov 1997-Nov 1999), researching and writing articles for the forthcoming Dictionary of Irish Biography, 9 vols (Cambridge, 2009) Research assistant, University of Aberdeen, Faculty of Modern History. (Oct 1996- Oct 1997) Bibliographer, Bibliography of British History, under the auspices of the Royal Historical Society and Cambridge University. -

The Vegetation, Ecology and Conservation of the Lough Oughter

T1 IL, V (11-:'A T 11 I' br 1909 pr-pared by Di` Jolun C0na1an., Cvl i_1alIl Darn, r_-talb4 1Y 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Page No. CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTION TO THE SURVEY 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Location and extent of the survey area 1 1.3 Geology, topography and soils 1 1.4 Climate 2 1.5 Land use 2 1.6 Importance of the site 3 1.7 Structure of the report 6 CHAPTER 2 - METHODS 2.1 Vegetation recording and mapping 7 CHAPTER 3 - VEGETATION DESCRIPTION 3.1 Introduction 9 3.2 Aquatic and species-poor swamp communities 11 3.2.1 Potamogeton lucens community 12 3.2.2 Littorella uniflora luncus articulatus community 13 3.2.3 Nuphar lutea community 14 3.2.4 Schoenoplectus lacustris community 15 3.2.5 Persicaria amphibium community 16 3.2.6 Menyanthes trifoliata community 17 3.2.7 Equisetum fluviatile community 18 3.2.8 Rumex hy&olapathum community 19 3.2.9 Lychnis fibs-cuculi - Lysmachia vulgaris community 20 3.2. 10 Phragmites australis community. 21 3.2. 11 Carex elata community 23 3.2.12 Carex rostrata community 24 3.2.13 Typha latifolia community 25 3.2.14 Sparganium erectum -A lisma plantago-aquatica community 26 3.2.15 Glyceria maxima community 27 3.2.16 Glyceria fluitans community 28 3.2.17 Eleocharis acicularis community 29 3.3 Species-rich swamp communities 30 3.3.1 Eleocharis palustris community 31 3.3.2 Carex vesicaria community 32 3.3.3 Phalaris arundinacea community 34 3.4 Wet grassland and tall-herb fen communities 36 3.4.1 Carex nigra - Potentilla anserina community 37 3.4.2 Juncus effuses - Senecio aquaticus community -

Sustaining Improvement Inspection (Involving Action Short Of

PRIMARY INSPECTION Brookeborough Primary School, Brookeborough, County Fermanagh Education and Training Inspectorate Controlled, co-educational Report of a Sustaining Improvement Inspection (Involving Action Short of Strike) in March 2017 Sustaining Improvement Inspection of Brookeborough Primary School, County Fermanagh (201-1894) Introduction In the last inspection held in September 2013, Brookeborough Primary School was evaluated overall as very good1. A sustaining improvement inspection (SII) was conducted on 8 March 2017. The purpose of the SII is to evaluate the extent to which the school is capable of demonstrating its capacity to effect improvement through self-evaluation and effective school development planning. Four of the teaching unions which make up the Northern Ireland Teachers’ Council (NITC) have declared industrial action primarily in relation to a pay dispute. This includes non-co-operation with the Education and Training Inspectorate (ETI). Prior to the inspection, the school informed the ETI that all of the teachers including the principal would not be co-operating with the inspectors. The ETI has a statutory duty to monitor, inspect and report on the quality of education under Article 102 of the Education and Libraries (Northern Ireland) Order 1986. Therefore, the inspection proceeded and the following evaluations are based on the evidence as made available at the time of the inspection. Focus of the inspection Owing to the school’s participation in industrial action: • the inspection was unable to focus on evaluating the extent to which the school is capable of demonstrating its capacity to effect improvement through self-evaluation and effective school development planning; and • lines of inquiry were not selected from the development plan priorities. -

Marriage Between the Irish and English of Fifteenth-Century Dublin, Meath, Louth and Kildare

Intermarriage in fifteenth-century Ireland: the English and Irish in the 'four obedient shires' Booker, S. (2013). Intermarriage in fifteenth-century Ireland: the English and Irish in the 'four obedient shires'. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Section C, Archaeology, Celtic Studies, History, Linguistics, Literature, 113, 219-250. https://doi.org/10.3318/PRIAC.2013.113.02 Published in: Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Section C, Archaeology, Celtic Studies, History, Linguistics, Literature Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2013 Royal Irish Academy. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:25. Sep. 2021 Intermarriage in fifteenth century Ireland: the English and Irish in the ‘four obedient shires’ SPARKY BOOKER* Department of History and Humanities, Trinity College Dublin [Accepted 1 March 2012.] Abstract Many attempts have been made to understand and explain the complicated relationship between the English of Ireland and the Irish in the later middle ages. -

REPEAL ASSOCATION..Wps

REPEAL ASSOCATION. Detroit-25 th July, 1844 To Daniel O’Donnell, Esq. M.P. Sir--The Detroit repealers beg leave respectfully to accompany their address by a mite of contribution towards the fine imposed on you, and solicit the favour of being allowed to participate in its payment. They would remit more largely, but are aware that others will also claim a like privilege. I am directed therefore to send you £20, and to solicit your acceptance of it towards the above object. We lately send 100/., to the Repeal Association, and within the past year another sum of 55/. Should there be any objection to our present request on your part or otherwise, we beg of you to apply it at your own discretion. I have the honour, Sir, to be your humble servant. H.H. Emmons, Corrres. Sec. Detroit Repeal Association. Contributers to the £20 send. C.H.Stewart, Dublin. Denis Mullane, Mallow, Co. Cork. Michael Dougherty, Newry. James Fitzmorris, Clonmel. Dr. James C. White, Mallow. James J. Hinde, Galway. John O’Callaghan, Braney, Co. Cork, one of the 1798 Patriots. (This could be Blarney). F.M. Grehie. Waterford. Michael Mahon, Limerick. George Gibson, Detroit. Christopher Cone, Tyrone, John Woods, Meath. Mr. and Mrs Hugh O’Beirne, Leitrim. James Leddy, Cavan. John Wade, Dublin, Denis O’Brien, Co. Kilkenny. James Collins, Omagh, Tyrone. Charles Moran, Detroit. Michael Kennedy, Waterford. Cornelius Dougherty, Tipperary. Thomas Sullivan, Cavan. Daniel Brislan, Tipperary. James Higgins, Kilkenny, Denis Lanigan, Kilkenny, John Sullivan, Mallow. Terence Reilly, Cavan, John Manning, Queens County. John Bermingham, Clare. Patrick MacTierney, Cavan. -

An Abstract of the Thesis Of

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Nicolas Evans for the degree of Master of Arts in English presented on June 2, 2017. Title: (Mis)representation & Postcolonial Masculinity: The Origins of Violence in the Plays and Films of Martin McDonagh. Abstract approved: ______________________________________________________ Neil R. Davison This thesis examines the postmodern confrontation of representation throughout the oeuvre of Martin McDonagh. I particularly look to his later body of work, which directly and self-reflexively confronts issues of artistic representation & masculinity, in order to gain a more nuanced understanding of his earliest and most controversial plays. In part, this thesis addresses misperceptions regarding The Leenane Trilogy, which was initially criticized for the plays’ shows of irreverence and use of caricature and cultural stereotypes. Rather than perpetuating propagandistic or offensive representations, my analysis explores how McDonagh uses affect and genre manipulation in order to parody artistic representation itself. Such a confrontation is meant to highlight the inadequacy of any representation to truly capture “authenticity.” Across his oeuvre, this postmodern proclivity is focused on disrupting the solidification of discourses of hyper-masculinity in the vein of postcolonial, diasporic, and mainstream media’s constructions of masculinity based on aggression and violence. ©Copyright by Nicolas Evans June 2, 2017 All Rights Reserved (Mis)representation & Postcolonial Masculinity: The Origins of Violence in the Plays and Films of Martin McDonagh by Nicolas Evans A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Presented June 2, 2017 Commencement June 2017 Master of Arts thesis of Nicolas Evans presented on June 2, 2017 APPROVED: Major Professor, representing English Director of the School of Writing, Literature, and Film Dean of the Graduate School I understand that my thesis will become part of the permanent collection of Oregon State University libraries. -

Athboy Heritage Trail Brochure.Pdf

Nobber Drogheda Oldcastle Slane Newgrange Bettystown Kells Laytown ne Donore oy er B Mosney iv Navan R Duleek Athboy Hill of N Tara 1 Trim Ratoath Dunshaughlin N Summerhill 2 Belfast Dunboyne N 3 0 5 Enfield M Kilcock Dublin N4 Galway Dublin Maynooth Shannon Cork Athboy is in County Meath, just a one hour drive from Dublin, and close to the heritage towns of Trim and Kells. It is also within easy driving distance of the major historical sites of Newgrange, Tara and Oldcastle. If you are interested in further information Standing at the Edge regarding heritage sites and tourist of the Pale attractions in Meath, please contact Meath Athboy Heritage Trail Tourism. The staff will also be delighted to assist you in reserving accommodation should you wish to spend a night or two in the area. Tourist Information Centre Railway Street, Navan, County Meath Telephone + 353 (0)46 73426 You may also wish to visit Meath Tourism’s website: www.meathtourism.ie This Heritage Trail is an application of the Meath Brand Identity, financed by LEADER II, the EU Initiative for Rural Development,1995–1999. At the Yellow Ford The town of Athboy began sometime during the sixth century A.D. as a settlement at the river crossing known as the Yellow Ford. The importance of the crossing meant that an established road network converging on the Yellow Ford had existed from early times. The town developed along these roadways. The earliest inhabitants of Athboy were Druids who had settlements at the nearby Hill of Ward. In 1180 the Anglo-Norman invasion reached Athboy.