Fallacies: Do We “Use” Them Or “Commit” Them? Or: Is All Our Life Just a Collection of Fallacies?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Logical Fallacies Moorpark College Writing Center

Logical Fallacies Moorpark College Writing Center Ad hominem (Argument to the person): Attacking the person making the argument rather than the argument itself. We would take her position on child abuse more seriously if she weren’t so rude to the press. Ad populum appeal (appeal to the public): Draws on whatever people value such as nationality, religion, family. A vote for Joe Smith is a vote for the flag. Alleged certainty: Presents something as certain that is open to debate. Everyone knows that… Obviously, It is obvious that… Clearly, It is common knowledge that… Certainly, Ambiguity and equivocation: Statements that can be interpreted in more than one way. Q: Is she doing a good job? A: She is performing as expected. Appeal to fear: Uses scare tactics instead of legitimate evidence. Anyone who stages a protest against the government must be a terrorist; therefore, we must outlaw protests. Appeal to ignorance: Tries to make an incorrect argument based on the claim never having been proven false. Because no one has proven that food X does not cause cancer, we can assume that it is safe. Appeal to pity: Attempts to arouse sympathy rather than persuade with substantial evidence. He embezzled a million dollars, but his wife had just died and his child needed surgery. Begging the question/Circular Logic: Proof simply offers another version of the question itself. Wrestling is dangerous because it is unsafe. Card stacking: Ignores evidence from the one side while mounting evidence in favor of the other side. Users of hearty glue say that it works great! (What is missing: How many users? Great compared to what?) I should be allowed to go to the party because I did my math homework, I have a ride there and back, and it’s at my friend Jim’s house. -

CHAPTER XXX. of Fallacies. Section 827. After Examining the Conditions on Which Correct Thoughts Depend, It Is Expedient to Clas

CHAPTER XXX. Of Fallacies. Section 827. After examining the conditions on which correct thoughts depend, it is expedient to classify some of the most familiar forms of error. It is by the treatment of the Fallacies that logic chiefly vindicates its claim to be considered a practical rather than a speculative science. To explain and give a name to fallacies is like setting up so many sign-posts on the various turns which it is possible to take off the road of truth. Section 828. By a fallacy is meant a piece of reasoning which appears to establish a conclusion without really doing so. The term applies both to the legitimate deduction of a conclusion from false premisses and to the illegitimate deduction of a conclusion from any premisses. There are errors incidental to conception and judgement, which might well be brought under the name; but the fallacies with which we shall concern ourselves are confined to errors connected with inference. Section 829. When any inference leads to a false conclusion, the error may have arisen either in the thought itself or in the signs by which the thought is conveyed. The main sources of fallacy then are confined to two-- (1) thought, (2) language. Section 830. This is the basis of Aristotle's division of fallacies, which has not yet been superseded. Fallacies, according to him, are either in the language or outside of it. Outside of language there is no source of error but thought. For things themselves do not deceive us, but error arises owing to a misinterpretation of things by the mind. -

Bias and Critical Thinking

BIAS AND CRITICAL THINKING Point: there is an alternative to • being “biased” (one-sided, closed-minded, etc.) • simply having an “opinion” (by which I mean a viewpoint that has subjective value only: “everyone has their own opinions”) • being neutral and not taking a position In thinking about bias, it is important to distinguish between four things: 1. a particular position taken on an issue 2. the source of that position (its support and basis) 3. the resistance or openness to other positions 4. the impact that position has on other positions and viewpoints taken by the person Too often, people confuse these four. One result is that people sometimes assume that taking any position on an issue (#1) is an indication of bias. If this were true, then the only way to avoid bias would be to not take a position but rather simply present what are considered to be facts. In this way one is supposedly “objective” and “neutral.” However, it is highly debatable whether one can really be objective and neutral or whether one can present objective facts in a completely neutral way. More importantly, there are two troublesome implications of such a viewpoint on bias: • the ideal would seem to be not taking a position (but to really deal with issues we have to take a position) • all positions are biased and therefore it is difficult if not impossible to judge one position superior to another. It is far better to reject the idea that taking any position always implies bias. Rather, bias is a function either of the source of that position, or the resistance one has to other positions, or the impact that position has on other positions and viewpoints taken. -

35 Fallacies

THIRTY-TWO COMMON FALLACIES EXPLAINED L. VAN WARREN Introduction If you watch TV, engage in debate, logic, or politics you have encountered the fallacies of: Bandwagon – "Everybody is doing it". Ad Hominum – "Attack the person instead of the argument". Celebrity – "The person is famous, it must be true". If you have studied how magicians ply their trade, you may be familiar with: Sleight - The use of dexterity or cunning, esp. to deceive. Feint - Make a deceptive or distracting movement. Misdirection - To direct wrongly. Deception - To cause to believe what is not true; mislead. Fallacious systems of reasoning pervade marketing, advertising and sales. "Get Rich Quick", phone card & real estate scams, pyramid schemes, chain letters, the list goes on. Because fallacy is common, you might want to recognize them. There is no world as vulnerable to fallacy as the religious world. Because there is no direct measure of whether a statement is factual, best practices of reasoning are replaced be replaced by "logical drift". Those who are political or religious should be aware of their vulnerability to, and exportation of, fallacy. The film, "Roshomon", by the Japanese director Akira Kurisawa, is an excellent study in fallacy. List of Fallacies BLACK-AND-WHITE Classifying a middle point between extremes as one of the extremes. Example: "You are either a conservative or a liberal" AD BACULUM Using force to gain acceptance of the argument. Example: "Convert or Perish" AD HOMINEM Attacking the person instead of their argument. Example: "John is inferior, he has blue eyes" AD IGNORANTIAM Arguing something is true because it hasn't been proven false. -

89% of Introduction-To-Psychology Textbooks That Define Or Explain

AMPXXX10.1177/2515245919858072Cassidy et al.Failing Grade 858072research-article2019 ASSOCIATION FOR General Article PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science Failing Grade: 89% of Introduction-to- 2019, Vol. 2(3) 233 –239 © The Author(s) 2019 Article reuse guidelines: Psychology Textbooks That Define sagepub.com/journals-permissions DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245919858072 10.1177/2515245919858072 or Explain Statistical Significance www.psychologicalscience.org/AMPPS Do So Incorrectly Scott A. Cassidy, Ralitza Dimova, Benjamin Giguère, Jeffrey R. Spence , and David J. Stanley Department of Psychology, University of Guelph Abstract Null-hypothesis significance testing (NHST) is commonly used in psychology; however, it is widely acknowledged that NHST is not well understood by either psychology professors or psychology students. In the current study, we investigated whether introduction-to-psychology textbooks accurately define and explain statistical significance. We examined 30 introductory-psychology textbooks, including the best-selling books from the United States and Canada, and found that 89% incorrectly defined or explained statistical significance. Incorrect definitions and explanations were most often consistent with the odds-against-chance fallacy. These results suggest that it is common for introduction- to-psychology students to be taught incorrect interpretations of statistical significance. We hope that our results will create awareness among authors of introductory-psychology books -

There Is No Fallacy of Arguing from Authority

There is no Fallacy ofArguing from Authority EDWIN COLEMAN University ofMelbourne Keywords: fallacy, argument, authority, speech act. Abstract: I argue that there is no fallacy of argument from authority. I first show the weakness of the case for there being such a fallacy: text-book presentations are confused, alleged examples are not genuinely exemplary, reasons given for its alleged fallaciousness are not convincing. Then I analyse arguing from authority as a complex speech act. R~iecting the popular but unjustified category of the "part-time fallacy", I show that bad arguments which appeal to authority are defective through breach of some felicity condition on argument as a speech act, not through employing a bad principle of inference. 1. Introduction/Summary There's never been a satisfactory theory of fallacy, as Hamblin pointed out in his book of 1970, in what is still the least unsatisfactory discussion. Things have not much improved in the last 25 years, despite fallacies getting more attention as interest in informal logic has grown. We still lack good answers to simple questions like what is a fallacy?, what fallacies are there? and how should we classifY fallacies? The idea that argument from authority (argumentum ad verecundiam) is a fallacy, is well-established in logical tradition. I argue that it is no such thing. The second main part of the paper is negative: I show the weakness of the case made in the literature for there being such a fallacy as argument from authority. First, text-book presentation of the fallacy is confused, second, the examples given are not genuinely exemplary and third, reasons given for its alleged fallaciousness are not convincing. -

The Nazi-Card-Card

ISSN 1751-8229 Volume Six, Number Three The Nazi-card-card Rasmus Ugilt, Aarhus University Introduction It should be made clear from the start that we all in fact already know the Nazi-card-card very well. At some point most of us have witnessed, or even been part of, a discussion that got just a little out of hand. In such situations it is not uncommon for one party to begin to draw up parallels between Germany in 1933 and his counterpart. Once this happens the counterpart will immediately play the Nazi-card-card and say something like, “Playing the Nazi-card are we? I never thought you would stoop that low. That is guaranteed to bring a quick end to any serious debate.” And just like that, the debate will in effect be over. It should be plain to anyone that it is just not right to make a Nazi of one’s opponent. The Nazi-card-card always wins. This tells us that it is in general unwise to play the Nazi-card, as it is bound to be immediately countered by the Nazi-card-card, but the lesson, I think, goes beyond mere rhetoric. Indeed, I believe that something quite profound and important goes on in situations like this, something which goes in a different direction to the perhaps more widely recognized Godwin’s Law, which could be formulated as follows: “As a discussion in an Internet forum grows longer, the probability of someone playing the Nazi-card approaches 1.” The more interesting law, I think, would be that 1 of the Nazi-card-card, which in similar language states: “The probability of someone playing the Nazi-card-card immediately after the Nazi-card has been played is always close to 1.” In the present work I seek to investigate and understand this curious second card. -

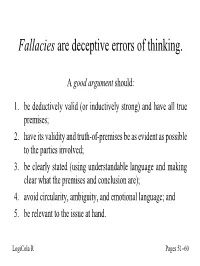

Fallacies Are Deceptive Errors of Thinking

Fallacies are deceptive errors of thinking. A good argument should: 1. be deductively valid (or inductively strong) and have all true premises; 2. have its validity and truth-of-premises be as evident as possible to the parties involved; 3. be clearly stated (using understandable language and making clear what the premises and conclusion are); 4. avoid circularity, ambiguity, and emotional language; and 5. be relevant to the issue at hand. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 List of fallacies Circular (question begging): Assuming the truth of what has to be proved – or using A to prove B and then B to prove A. Ambiguous: Changing the meaning of a term or phrase within the argument. Appeal to emotion: Stirring up emotions instead of arguing in a logical manner. Beside the point: Arguing for a conclusion irrelevant to the issue at hand. Straw man: Misrepresenting an opponent’s views. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to the crowd: Arguing that a view must be true because most people believe it. Opposition: Arguing that a view must be false because our opponents believe it. Genetic fallacy: Arguing that your view must be false because we can explain why you hold it. Appeal to ignorance: Arguing that a view must be false because no one has proved it. Post hoc ergo propter hoc: Arguing that, since A happened after B, thus A was caused by B. Part-whole: Arguing that what applies to the parts must apply to the whole – or vice versa. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to authority: Appealing in an improper way to expert opinion. -

Critical Review All While Still Others Are Characterized Inadequately Or Incompletely

12 Some should not be classified as fallacies of relevance at critical review all while still others are characterized inadequately or incompletely. Copi maintains that in all fallacies of rele vance "their premisses are logically irrelevant to, and therefore incapable of establishing the truth of their conclusions" (pp. 9S-99). But this definition does not apply to the most important of the fallacies of relevance, the irrelevant conclusion (ignoratio elenchi). According to Copi, this fallacy is committed "when an argument sup Copi's Sixth Edition posedly intended to establish a particular conclusion is directed to proving a different conclusion" (p. 110). Copi even allows that the fallacy can be committed by one who may" succeed in proving his (irrelevant) conclusion" (my italics). The fault then is not that the premisses of such Ronald Roblin arguments are logically irrelevant to the conclusion drawn State University College at Buffalo from them, but that the conclusion drawn is insufficient to justify the conclusion called for by the context. If a prosecutor, purporting to prove the defendant guilty of murder, shows on Iy that he had sufficient opportunity and Copi, Irving. Introduction to l~gic. 6th edition. New motive to commit the crime, he (the prosecutor) commits York: Macmillan, 19S2. x. 604 pp.ISBN o-02-324920-X the fallacy of insufficient conclusion. If, on the other hand, he succeeds only in "proving" that murder is a horrible crime, he is guilty of an ignoratio elenchi. In effect, then, The sixth edition of this widely used and influential text Copi does not distinguish between two different fal is worth reviewing, first. -

The Trespass Fallacy in Patent Law , 65 Fla

Florida Law Review Volume 65 | Issue 6 Article 1 October 2013 The rT espass Fallacy in Patent Law Adam Mossoff Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr Part of the Intellectual Property Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation Adam Mossoff, The Trespass Fallacy in Patent Law , 65 Fla. L. Rev. 1687 (2013). Available at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr/vol65/iss6/1 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Law Review by an authorized administrator of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mossoff: The Trespass Fallacy in Patent Law Florida Law Review Founded 1948 VOLUME 65 DECEMBER 2013 NUMBER 6 ESSAYS THE TRESPASS FALLACY IN PATENT LAW Adam Mossoff∗ Abstract The patent system is broken and in dire need of reform; so says the popular press, scholars, lawyers, judges, congresspersons, and even the President. One common complaint is that patents are now failing as property rights because their boundaries are not as clear as the fences that demarcate real estate—patent infringement is neither as determinate nor as efficient as trespass is for land. This Essay explains that this is a fallacious argument, suffering both empirical and logical failings. Empirically, there are no formal studies of trespass litigation rates; thus, complaints about the patent system’s indeterminacy are based solely on an idealized theory of how trespass should function, which economists identify as the “nirvana fallacy.” Furthermore, anecdotal evidence and other studies suggest that boundary disputes between landowners are neither as clear nor as determinate as patent scholars assume them to be. -

An Introduction to Philosophy

An Introduction to Philosophy W. Russ Payne Bellevue College Copyright (cc by nc 4.0) 2015 W. Russ Payne Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document with attribution under the terms of Creative Commons: Attribution Noncommercial 4.0 International or any later version of this license. A copy of the license is found at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ 1 Contents Introduction ………………………………………………. 3 Chapter 1: What Philosophy Is ………………………….. 5 Chapter 2: How to do Philosophy ………………….……. 11 Chapter 3: Ancient Philosophy ………………….………. 23 Chapter 4: Rationalism ………….………………….……. 38 Chapter 5: Empiricism …………………………………… 50 Chapter 6: Philosophy of Science ………………….…..… 58 Chapter 7: Philosophy of Mind …………………….……. 72 Chapter 8: Love and Happiness …………………….……. 79 Chapter 9: Meta Ethics …………………………………… 94 Chapter 10: Right Action ……………………...…………. 108 Chapter 11: Social Justice …………………………...…… 120 2 Introduction The goal of this text is to present philosophy to newcomers as a living discipline with historical roots. While a few early chapters are historically organized, my goal in the historical chapters is to trace a developmental progression of thought that introduces basic philosophical methods and frames issues that remain relevant today. Later chapters are topically organized. These include philosophy of science and philosophy of mind, areas where philosophy has shown dramatic recent progress. This text concludes with four chapters on ethics, broadly construed. I cover traditional theories of right action in the third of these. Students are first invited first to think about what is good for themselves and their relationships in a chapter of love and happiness. Next a few meta-ethical issues are considered; namely, whether they are moral truths and if so what makes them so. -

Quantifying Aristotle's Fallacies

mathematics Article Quantifying Aristotle’s Fallacies Evangelos Athanassopoulos 1,* and Michael Gr. Voskoglou 2 1 Independent Researcher, Giannakopoulou 39, 27300 Gastouni, Greece 2 Department of Applied Mathematics, Graduate Technological Educational Institute of Western Greece, 22334 Patras, Greece; [email protected] or [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 20 July 2020; Accepted: 18 August 2020; Published: 21 August 2020 Abstract: Fallacies are logically false statements which are often considered to be true. In the “Sophistical Refutations”, the last of his six works on Logic, Aristotle identified the first thirteen of today’s many known fallacies and divided them into linguistic and non-linguistic ones. A serious problem with fallacies is that, due to their bivalent texture, they can under certain conditions disorient the nonexpert. It is, therefore, very useful to quantify each fallacy by determining the “gravity” of its consequences. This is the target of the present work, where for historical and practical reasons—the fallacies are too many to deal with all of them—our attention is restricted to Aristotle’s fallacies only. However, the tools (Probability, Statistics and Fuzzy Logic) and the methods that we use for quantifying Aristotle’s fallacies could be also used for quantifying any other fallacy, which gives the required generality to our study. Keywords: logical fallacies; Aristotle’s fallacies; probability; statistical literacy; critical thinking; fuzzy logic (FL) 1. Introduction Fallacies are logically false statements that are often considered to be true. The first fallacies appeared in the literature simultaneously with the generation of Aristotle’s bivalent Logic. In the “Sophistical Refutations” (Sophistici Elenchi), the last chapter of the collection of his six works on logic—which was named by his followers, the Peripatetics, as “Organon” (Instrument)—the great ancient Greek philosopher identified thirteen fallacies and divided them in two categories, the linguistic and non-linguistic fallacies [1].