Supporting Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Late Jurassic Theropod Dinosaur Bones from the Langenberg Quarry

Late Jurassic theropod dinosaur bones from the Langenberg Quarry (Lower Saxony, Germany) provide evidence for several theropod lineages in the central European archipelago Serjoscha W. Evers1 and Oliver Wings2 1 Department of Geosciences, University of Fribourg, Fribourg, Switzerland 2 Zentralmagazin Naturwissenschaftlicher Sammlungen, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Halle (Saale), Germany ABSTRACT Marine limestones and marls in the Langenberg Quarry provide unique insights into a Late Jurassic island ecosystem in central Europe. The beds yield a varied assemblage of terrestrial vertebrates including extremely rare bones of theropod from theropod dinosaurs, which we describe here for the first time. All of the theropod bones belong to relatively small individuals but represent a wide taxonomic range. The material comprises an allosauroid small pedal ungual and pedal phalanx, a ceratosaurian anterior chevron, a left fibula of a megalosauroid, and a distal caudal vertebra of a tetanuran. Additionally, a small pedal phalanx III-1 and the proximal part of a small right fibula can be assigned to indeterminate theropods. The ontogenetic stages of the material are currently unknown, although the assignment of some of the bones to juvenile individuals is plausible. The finds confirm the presence of several taxa of theropod dinosaurs in the archipelago and add to our growing understanding of theropod diversity and evolution during the Late Jurassic of Europe. Submitted 13 November 2019 Accepted 19 December 2019 Subjects Paleontology, -

Evaluating the Ecology of Spinosaurus: Shoreline Generalist Or Aquatic Pursuit Specialist?

Palaeontologia Electronica palaeo-electronica.org Evaluating the ecology of Spinosaurus: Shoreline generalist or aquatic pursuit specialist? David W.E. Hone and Thomas R. Holtz, Jr. ABSTRACT The giant theropod Spinosaurus was an unusual animal and highly derived in many ways, and interpretations of its ecology remain controversial. Recent papers have added considerable knowledge of the anatomy of the genus with the discovery of a new and much more complete specimen, but this has also brought new and dramatic interpretations of its ecology as a highly specialised semi-aquatic animal that actively pursued aquatic prey. Here we assess the arguments about the functional morphology of this animal and the available data on its ecology and possible habits in the light of these new finds. We conclude that based on the available data, the degree of adapta- tions for aquatic life are questionable, other interpretations for the tail fin and other fea- tures are supported (e.g., socio-sexual signalling), and the pursuit predation hypothesis for Spinosaurus as a “highly specialized aquatic predator” is not supported. In contrast, a ‘wading’ model for an animal that predominantly fished from shorelines or within shallow waters is not contradicted by any line of evidence and is well supported. Spinosaurus almost certainly fed primarily from the water and may have swum, but there is no evidence that it was a specialised aquatic pursuit predator. David W.E. Hone. Queen Mary University of London, Mile End Road, London, E1 4NS, UK. [email protected] Thomas R. Holtz, Jr. Department of Geology, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland 20742 USA and Department of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC 20560 USA. -

A New Crested Theropod Dinosaur from the Early Jurassic of Yunnan

第55卷 第2期 古 脊 椎 动 物 学 报 pp. 177-186 2017年4月 VERTEBRATA PALASIATICA figs. 1-3 A new crested theropod dinosaur from the Early Jurassic of Yunnan Province, China WANG Guo-Fu1,2 YOU Hai-Lu3,4* PAN Shi-Gang5 WANG Tao5 (1 Fossil Research Center of Chuxiong Prefecture, Yunnan Province Chuxiong, Yunnan 675000) (2 Chuxiong Prefectural Museum Chuxiong, Yunnan 675000) (3 Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences Beijing 100044 * Corresponding author: [email protected]) (4 College of Earth Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences Beijing 100049) (5 Bureau of Land and Resources of Lufeng County Lufeng, Yunnan 650031) Abstract A new crested theropod, Shuangbaisaurus anlongbaoensis gen. et sp. nov., is reported. The new taxon is recovered from the Lower Jurassic Fengjiahe Formation of Shuangbai County, Chuxiong Yi Autonomous Prefecture, Yunnan Province, and is represented by a partial cranium. Shuangbaisaurus is unique in possessing parasagittal crests along the orbital dorsal rims. It is also distinguishable from the other two lager-bodied parasagittal crested Early Jurassic theropods (Dilophosaurus and Sinosaurus) by a unique combination of features, such as higher than long premaxillary body, elevated ventral edge of the premaxilla, and small upper temporal fenestra. Comparative morphological study indicates that “Dilophosaurus” sinensis could potentially be assigned to Sinosaurus, but probably not to the type species. The discovery of Shuangbaisaurus will help elucidate the evolution of basal theropods, especially the role of various bony cranial ornamentations had played in the differentiation of early theropods. -

Xjiiie'icanj/Useum

XJiiie'ican1ox4tatreJ/useum PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST AT 79TH STREET, NEW YORK 24, N.Y. NUMBER 2I8I JUNE 4, I964 Relationships of the Saurischian Dinosaurs BY EDWIN H. COLBERT1 INTRODUCTION The word "Dinosauria" was coined by Sir Richard Owen in 1842 as a designation for various genera and species of extinct reptiles, the fossil bones of which were then being discovered and described in Europe. For many years this term persisted as the name for one order of reptiles and thus became well intrenched within the literature of paleontology. In- deed, since this name was associated with fossil remains that are frequently of large dimensions and spectacular shape and therefore of considerable interest to the general public, it in time became Anglicized, to take its proper place as a common noun in the English language. Almost every- body in the world is today more or less familiar with dinosaurs. As long ago as 1888, H. G. Seeley recognized the fact that the dino- saurs are not contained within a single reptilian order, but rather are quite clearly members of two distinct orders, each of which can be de- fined on the basis of many osteological characters. The structure of the pelvis is particularly useful in the separation of the two dinosaurian orders, and consequently Seeley named these two major taxonomic categories the Saurischia and the Ornithischia. This astute observation by Seeley was not readily accepted, so that for many years following the publication of his original paper proposing the basic dichotomy of the dinosaurs the 1 Chairman and Curator, Department ofVertebrate Paleontology, the American Museum of Natural History. -

The Adaptations of Antarctic Dinosaurs "Exploration Is the Physical Expression of the Intellectual Passion

The Adaptations of Antarctic Dinosaurs "Exploration is the physical expression of the Intellectual Passion. And I tell you, if you have the desire for knowledge and the power to give it physical expression, go out and explore. If you are a brave man you will do nothing: if you are fearful you may do much, for none but cowards have need to prove their bravery. Some will tell you that you are mad, and nearly all will say, "What is the use?" For we are a nation of shopkeepers, and no shopkeeper will look at research which does not promise him a financial return within a year. And so you will sledge nearly alone, but those with whom you sledge will not be shopkeepers: that is worth a good deal. If you march your Winter Journeys you will have your reward, so long as all you want is a penguin's egg." —Apsley Cherry-Garrard, "The Worst Journey in the World" Life Long Ago in the Antarctic Long ago during the age of the dinosaurs the basics of life and survival were not so different from today. Life was in great abundance and creatures of all sizes walked, stomped, crept and slunk all over the earth. Although many of the animals have changed and disappeared, the way all animals live have remained the same. They still need to eat, sleep and be safe. They still all strive to find way to raise a family and be happy. This was true even 185 million years ago in the continent we now call Antarctica. -

Dinosaurs British Isles

DINOSAURS of the BRITISH ISLES Dean R. Lomax & Nobumichi Tamura Foreword by Dr Paul M. Barrett (Natural History Museum, London) Skeletal reconstructions by Scott Hartman, Jaime A. Headden & Gregory S. Paul Life and scene reconstructions by Nobumichi Tamura & James McKay CONTENTS Foreword by Dr Paul M. Barrett.............................................................................10 Foreword by the authors........................................................................................11 Acknowledgements................................................................................................12 Museum and institutional abbreviations...............................................................13 Introduction: An age-old interest..........................................................................16 What is a dinosaur?................................................................................................18 The question of birds and the ‘extinction’ of the dinosaurs..................................25 The age of dinosaurs..............................................................................................30 Taxonomy: The naming of species.......................................................................34 Dinosaur classification...........................................................................................37 Saurischian dinosaurs............................................................................................39 Theropoda............................................................................................................39 -

Implications for Predatory Dinosaur Macroecology and Ontogeny in Later Late Cretaceous Asiamerica

Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Theropod Guild Structure and the Tyrannosaurid Niche Assimilation Hypothesis: Implications for Predatory Dinosaur Macroecology and Ontogeny in later Late Cretaceous Asiamerica Journal: Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Manuscript ID cjes-2020-0174.R1 Manuscript Type: Article Date Submitted by the 04-Jan-2021 Author: Complete List of Authors: Holtz, Thomas; University of Maryland at College Park, Department of Geology; NationalDraft Museum of Natural History, Department of Geology Keyword: Dinosaur, Ontogeny, Theropod, Paleocology, Mesozoic, Tyrannosauridae Is the invited manuscript for consideration in a Special Tribute to Dale Russell Issue? : © The Author(s) or their Institution(s) Page 1 of 91 Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 1 Theropod Guild Structure and the Tyrannosaurid Niche Assimilation Hypothesis: 2 Implications for Predatory Dinosaur Macroecology and Ontogeny in later Late Cretaceous 3 Asiamerica 4 5 6 Thomas R. Holtz, Jr. 7 8 Department of Geology, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742 USA 9 Department of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC 20013 USA 10 Email address: [email protected] 11 ORCID: 0000-0002-2906-4900 Draft 12 13 Thomas R. Holtz, Jr. 14 Department of Geology 15 8000 Regents Drive 16 University of Maryland 17 College Park, MD 20742 18 USA 19 Phone: 1-301-405-4084 20 Fax: 1-301-314-9661 21 Email address: [email protected] 22 23 1 © The Author(s) or their Institution(s) Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Page 2 of 91 24 ABSTRACT 25 Well-sampled dinosaur communities from the Jurassic through the early Late Cretaceous show 26 greater taxonomic diversity among larger (>50kg) theropod taxa than communities of the 27 Campano-Maastrichtian, particularly to those of eastern/central Asia and Laramidia. -

Upper Cretaceous), Brazil

Rev. Mus. Argentino Cienc. Nat., n.s. 7(1): 31-36, 2005 Buenos Aires, ISSN 1514-5158 Maniraptoran theropod ungual from the Marília Formation (Upper Cretaceous), Brazil Fernando E. NOVAS1, Luiz Carlos BORGES RIBEIRO2,3 & Ismar de SOUZA CARVALHO4 1CONICET - Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales «Bernardino Rivadavia», Av. Angel Gallardo 470, Buenos Aires (1405), Argentina, E-mail: [email protected]. 2Fundação Municipal de Ensino Superior de Uberaba- FUMESU/Centro de Pesquisas Paleontológicas L. I. Price. Av. Randolfo Borges Jr., n° 1.250. Universidade, 38.066-005, Uberaba- MG, Brazil, E-mail: [email protected]. 3Universidade de Uberaba-UNIUBE/Instituto de Formação de Educadores-Departamento de Biologia, Av. Nenê Sabino, n° 1.801. Universitário, Uberaba-MG, 38.055-500, Brazil, E-mail: [email protected]. 4Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Departamento de Geologia, CCMN/IGEO. 21.949-900 Cidade Universitária-Ilha do Fundão, Rio de Janeiro-RJ, Brazil, E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: A new theropod record from the Marília Formation (Late Cretaceous, Minas Gerais, Brazil) is here described. It consists of an isolated manual ungual which exhibits derived maniraptoran features (e.g., presence of proximodorsal lip). The ungual distinguishes by a set of unique features (e.g., dorsoventrally low and proximodistally elongate profile in side view; block-like flexor tuberosity; proximal articular surface more dorsally oriented than in other theropods; cutting «keel» located distally on ventral surface) suggesting that the animal that produced it was a member of an unknown group of derived maniraptoran theropods, other than alvarezsaurids, deinonychosaurians and oviraptorosaurians already recorded in South America. -

Dinosaur Species List E to M

Dinosaur Species List E to M E F G • Echinodon becklesii • Fabrosaurus australis • Gallimimus bullatus • Edmarka rex • Frenguellisaurus • Garudimimus brevipes • Edmontonia longiceps ischigualastensis • Gasosaurus constructus • Edmontonia rugosidens • Fulengia youngi • Gasparinisaura • Edmontosaurus annectens • Fulgurotherium australe cincosaltensis • Edmontosaurus regalis • Genusaurus sisteronis • Edmontosaurus • Genyodectes serus saskatchewanensis • Geranosaurus atavus • Einiosaurus procurvicornis • Gigantosaurus africanus • Elaphrosaurus bambergi • Giganotosaurus carolinii • Elaphrosaurus gautieri • Gigantosaurus dixeyi • Elaphrosaurus iguidiensis • Gigantosaurus megalonyx • Elmisaurus elegans • Gigantosaurus robustus • Elmisaurus rarus • Gigantoscelus • Elopteryx nopcsai molengraaffi • Elosaurus parvus • Gilmoreosaurus • Emausaurus ernsti mongoliensis • Embasaurus minax • Giraffotitan altithorax • Enigmosaurus • Gongbusaurus shiyii mongoliensis • Gongbusaurus • Eoceratops canadensis wucaiwanensis • Eoraptor lunensis • Gorgosaurus lancensis • Epachthosaurus sciuttoi • Gorgosaurus lancinator • Epanterias amplexus • Gorgosaurus libratus • Erectopus sauvagei • "Gorgosaurus" novojilovi • Erectopus superbus • Gorgosaurus sternbergi • Erlikosaurus andrewsi • Goyocephale lattimorei • Eucamerotus foxi • Gravitholus albertae • Eucercosaurus • Gresslyosaurus ingens tanyspondylus • Gresslyosaurus robustus • Eucnemesaurus fortis • Gresslyosaurus torgeri • Euhelopus zdanskyi • Gryponyx africanus • Euoplocephalus tutus • Gryponyx taylori • Euronychodon -

The Nonavian Theropod Quadrate II: Systematic Usefulness, Major Trends and Cladistic and Phylogenetic Morphometrics Analyses

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272162807 The nonavian theropod quadrate II: systematic usefulness, major trends and cladistic and phylogenetic morphometrics analyses Article · January 2014 DOI: 10.7287/peerj.preprints.380v2 CITATION READS 1 90 3 authors: Christophe Hendrickx Ricardo Araujo University of the Witwatersrand Technical University of Lisbon 37 PUBLICATIONS 210 CITATIONS 89 PUBLICATIONS 324 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Octávio Mateus University NOVA of Lisbon 224 PUBLICATIONS 2,205 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Nature and Time on Earth - Project for a course and a book for virtual visits to past environments in learning programmes for university students (coordinators Edoardo Martinetto, Emanuel Tschopp, Robert A. Gastaldo) View project Ten Sleep Wyoming Jurassic dinosaurs View project All content following this page was uploaded by Octávio Mateus on 12 February 2015. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. The nonavian theropod quadrate II: systematic usefulness, major trends and cladistic and phylogenetic morphometrics analyses Christophe Hendrickx1,2 1Universidade Nova de Lisboa, CICEGe, Departamento de Ciências da Terra, Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia, Quinta da Torre, 2829-516, Caparica, Portugal. 2 Museu da Lourinhã, 9 Rua João Luis de Moura, 2530-158, Lourinhã, Portugal. s t [email protected] n i r P e 2,3,4,5 r Ricardo Araújo P 2 Museu da Lourinhã, 9 Rua João Luis de Moura, 2530-158, Lourinhã, Portugal. 3 Huffington Department of Earth Sciences, Southern Methodist University, PO Box 750395, 75275-0395, Dallas, Texas, USA. -

Hierarchical Clustering Analysis Suppcdr.Cdr

Distance Hierarchical joiningclustering 3.0 2.5 2.0 1.5 1.0 0.5 Sinosauropteryx Caudipteryx Eoraptor Compsognathus Compsognathus Compsognathus Compsognathus Megaraptora basal Coelurosauria Noasauridae Neotheropoda non-averostran T non-tyrannosaurid Dromaeosauridae basalmost Theropoda Oviraptorosauria Compsognathidae Therizinosauria T A yrannosauroidea Compsognathus roodontidae ves Compsognathus Compsognathus Compsognathus Compsognathus Compsognathus Compsognathus Compsognathus Compsognathus Compsognathus Compsognathus Compsognathus Compsognathus Compsognathus Richardoestesia Scipionyx Buitreraptor Compsognathus Troodon Compsognathus Compsognathus Compsognathus Juravenator Sinosauropteryx Juravenator Juravenator Sinosauropteryx Incisivosaurus Coelophysis Scipionyx Richardoestesia Compsognathus Compsognathus Compsognathus Richardoestesia Richardoestesia Richardoestesia Richardoestesia Compsognathus Richardoestesia Juravenator Richardoestesia Richardoestesia Richardoestesia Richardoestesia Buitreraptor Saurornitholestes Ichthyornis Saurornitholestes Ichthyornis Richardoestesia Richardoestesia Richardoestesia Richardoestesia Richardoestesia Juravenator Scipionyx Buitreraptor Coelophysis Richardoestesia Coelophysis Richardoestesia Richardoestesia Richardoestesia Richardoestesia Coelophysis Richardoestesia Bambiraptor Richardoestesia Richardoestesia Velociraptor Juravenator Saurornitholestes Saurornitholestes Buitreraptor Coelophysis Coelophysis Ornitholestes Richardoestesia Richardoestesia Juravenator Saurornitholestes Velociraptor Saurornitholestes -

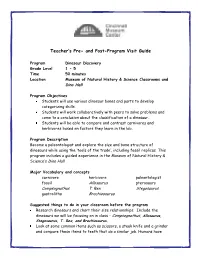

Teacher's Pre- and Post-Program Visit Guide

Teacher’s Pre- and Post-Program Visit Guide Program Dinosaur Discovery Grade Level 1 - 5 Time 50 minutes Location Museum of Natural History & Science Classrooms and Dino Hall Program Objectives Students will use various dinosaur bones and parts to develop categorizing skills. Students will work collaboratively with peers to solve problems and come to a conclusion about the classification of a dinosaur. Students will be able to compare and contrast carnivores and herbivores based on factors they learn in the lab. Program Description Become a paleontologist and explore the size and bone structure of dinosaurs while using the „tools of the trade‟, including fossil replicas. This program includes a guided experience in the Museum of Natural History & Science‟s Dino Hall. Major Vocabulary and concepts carnivore herbivore paleontologist fossil Allosaurus pterosaurs Compsognathus T. Rex Stegosaurus gastroliths Brachiosaurus Suggested things to do in your classroom before the program Research dinosaurs and chart their size relationships. Include the dinosaurs we will be focusing on in class – Compsognathus, Allosaurus, Stegosaurus, T. Rex, and Brachiosaurus. Look at some common items such as scissors, a steak knife and a grinder and compare these items to teeth that do a similar job. Humans have three types of teeth, incisors for cutting/snipping (scissors); canines for stabbing/slicing (steak knife); and molars for grinding and crunching (grinder). Have them look at pictures of dinosaurs and decide which kind of teeth each animal has. Use a