The Spirit of Contradiction in the Buddhist Doctrine of Not-Self

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Self and Non-Self in Early Buddhism (Joaquin Pérez-Remón)

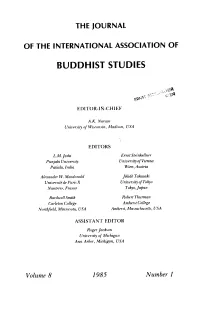

THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BUDDHIST STUDIES EDITOR-IN-CHIEF A.K. Narain University of Wisconsin, Madison, USA EDITORS L.M.Joshi Ernst Steinkellner Punjabi University University of Vienna PatiaUi, India Wien, Austria Alexander W. Macdonald Jikido Takasaki Universitede Paris X University of Tokyo Nanterre, France Tokyo,Japan Hardwell Smith Robert Thurman Carleton College Amherst College Northjield, Minnesota, USA Amherst, Massachusetts, USA ASSISTANT EDITOR Roger Jackson University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA Volume 8 1985 Number I CONTENTS I. ARTICLES J. Nagarjuna's Arguments Against Motion, by Kamaleswar Bhattacharya 7 2. Dharani and Pratibhdna: Memory and Eloquence of the Bodhisattvas, by J ens Braarvig 17 3. The Concept of a "Creator God" in Tantric Buddhism, by Eva K. Dargyay 31 4. Direct Perception (Pratyakja) in dGe-iugs-pa Interpre tations of Sautrantika,^/lnw^C. Klein 49 5. A Text-Historical Note on Hevajratantra II: v: 1-2, by lj>onard W.J. van der Kuijp 83 6. Simultaneous Relation (Sahabhu-hetu): A Study in Bud dhist Theory of Causation, by Kenneth K. Tanaka 91 II. BOOK REVIEWS AND NOTICES Reviews: 1. The Books o/Kiu- Te or the Tibetan Buddhist Tantras: A Pre liminary Analysis, by David Reigle Dzog Chen and Zen, by Namkhai Norbu (Roger Jackson) 113 2. Nagarjuniana. Studies in the Writings and Philosophy of Ndgdrjuna, by Chr. Lindtner (Fernando Tola and Carmen Dragonetti) 115 3. Selfless Persons: Imagery and Thought in Theravada Bud dhism, by Steven Collins (Vijitha Rajapakse) 117 4. Self and Non-Self in Early Buddhism, by Joaquin Perez- Remon (VijithaRajapkse) 122 5. -

A Study of the Saṃskāra Section of Vasubandhu's Pañcaskandhaka with Reference to Its Commentary by Sthiramati

A Study of the Saṃskāra Section of Vasubandhu's Pañcaskandhaka with Reference to Its Commentary by Sthiramati Jowita KRAMER 1. Introduction In his treatise "On the Five Constituents of the Person" (Pañcaskandhaka) Vasubandhu succeeded in presenting a brief but very comprehensive and clear outline of the concept of the five skandhas as understood from the viewpoint of the Yogācāra tradition. When investigating the doctrinal development of the five skandha theory and of other related concepts taught in the Pañcaskandhaka, works like the Yogācārabhūmi, the Abhidharmasamuccaya, and the Abhidharmakośa- bhāṣya are of great importance. The relevance of the first two texts results from their close association with the Pañcaskandhaka in terms of tradition. The significance of the Abhidharmakośabhāṣya is due to the assumption of an identical author of this text and the Pañcaskandhaka.1 The comparison of the latter with the other texts leads to a highly inconsistent picture of the relations between the works. It is therefore difficult to determine the developmental processes of the teachings presented in the texts under consideration and to give a concluding answer to the question whether the same person composed the Abhidharmakośabhāṣya and the Pañcaskandhaka. What makes the identification of the interdependence between the texts even more problematic is our limited knowledge of the methods the Indian authors and commentators applied when they composed their works. It was obviously very common to make use of whole sentences or even passages from older texts without marking them as quotations. If we assume the silent copying of older material as the usual method of Indian authors, then the question arises why in some cases the wording they apply is not identical but replaced by synonyms or completely different statements. -

Studies in Buddhist Hetuvidyā (Epistemology and Logic ) in Europe and Russia

Nataliya Kanaeva STUDIES IN BUDDHIST HETUVIDYĀ (EPISTEMOLOGY AND LOGIC ) IN EUROPE AND RUSSIA Working Paper WP20/2015/01 Series WP20 Philosophy of Culture and Cultural Studies Moscow 2015 УДК 24 ББК 86.36 K19 Editor of the series WP20 «Philosophy of Culture and Cultural Studies» Vitaly Kurennoy Kanaeva, Nataliya. K19 Studies in Buddhist Hetuvidyā (Epistemology and Logic ) in Europe and Russia [Text] : Working paper WP20/2015/01 / N. Kanaeva ; National Research University Higher School of Economics. – Moscow : Higher School of Economics Publ. House, 2015. – (Series WP20 “Philosophy of Culture and Cultural Studiesˮ) – 52 p. – 20 copies. This publication presents an overview of the situation in studies of Buddhist epistemology and logic in Western Europe and in Russia. Those studies are the young direction of Buddhology, and they started only at the beginning of the XX century. There are considered the main schools, their representatives, the directions of their researches and achievements in the review. The activity of Russian scientists in this field was not looked through ever before. УДК 24 ББК 86.36 This study (research grant № 14-01-0006) was supported by The National Research University Higher School of Economics (Moscow). Academic Fund Program in 2014–2015. Kanaeva Nataliya – National Research University Higher School of Economics (Moscow). Department of Humanities. School of Philosophy. Assistant professor; [email protected]. Канаева, Н. А. Исследования буддийской хетувидьи (эпистемологии и логики) в Европе и России (обзор) [Текст] : препринт WP20/2015/01 / Н. А. Канаева ; Нац. исслед. ун-т «Высшая школа экономи- ки». – М.: Изд. дом Высшей школы экономики, 2015. – (Серия WP20 «Философия и исследо- вания культуры»). -

The Scientific Evidence of the Buddhist Teaching's Separation Body

International Journal of Philosophy 2015; 3(2): 12-23 Published online July 2, 2015 (http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ijp) doi: 10.11648/j.ijp.20150302.11 ISSN: 2330-7439 (Print); ISSN: 2330-7455 (Online) The Scientific Evidence of the Buddhist Teaching’s Separation Body and Mind When Humans and Animals Die Jargal Dorj ONCH-USA, Co., Chicago Email address: [email protected] To cite this article: Jargal Dorj. The Scientific Evidence of the Buddhist Teaching’s Separation Body and Mind When Humans and Animals Die. International Journal of Philosophy . Vol. 3, No. 2, 2015, pp. 12-23. doi: 10.11648/j.ijp.20150302.11 Abstract: This article proves that the postulate "the body and mind of humans and animals are seperated, when they die" has a theoretical proof, empirical testament and has its own unique interpretation. The Buddhist philosophy assumes that there are not-eternal and eternal universe and they have their own objects and phenomena. Actually, there is also a neutral universe and phenomena. We show, and make sure that there is also a neutral phenomena and universe, the hybrid mind and time that belongs to neutral universe. We take the Buddhist teachings in order to reduce suffering and improve rebirth and, and three levels of Enlightenment. Finally, due to the completion evidence of the Law of Karma as a whole, it has given the conclusion associated with the Law of Karma. Keywords: Body, Spirit, Soul, Mind, Karma, Buddha, Nirvana, Samadhi “If there is any religion that would cope with modern may not be able to believe in it assuming this could be a scientific needs, it would be Buddhism” religious superstition. -

Metaphor and Literalism in Buddhism

METAPHOR AND LITERALISM IN BUDDHISM The notion of nirvana originally used the image of extinguishing a fire. Although the attainment of nirvana, ultimate liberation, is the focus of the Buddha’s teaching, its interpretation has been a constant problem to Buddhist exegetes, and has changed in different historical and doctrinal contexts. The concept is so central that changes in its understanding have necessarily involved much larger shifts in doctrine. This book studies the doctrinal development of the Pali nirvana and sub- sequent tradition and compares it with the Chinese Agama and its traditional interpretation. It clarifies early doctrinal developments of nirvana and traces the word and related terms back to their original metaphorical contexts. Thereby, it elucidates diverse interpretations and doctrinal and philosophical developments in the abhidharma exegeses and treatises of Southern and Northern Buddhist schools. Finally, the book examines which school, if any, kept the original meaning and reference of nirvana. Soonil Hwang is Assistant Professor in the Department of Indian Philosophy at Dongguk University, Seoul. His research interests are focused upon early Indian Buddhism, Buddhist Philosophy and Sectarian Buddhism. ROUTLEDGE CRITICAL STUDIES IN BUDDHISM General Editors: Charles S. Prebish and Damien Keown Routledge Critical Studies in Buddhism is a comprehensive study of the Buddhist tradition. The series explores this complex and extensive tradition from a variety of perspectives, using a range of different methodologies. The series is diverse in its focus, including historical studies, textual translations and commentaries, sociological investigations, bibliographic studies, and considera- tions of religious practice as an expression of Buddhism’s integral religiosity. It also presents materials on modern intellectual historical studies, including the role of Buddhist thought and scholarship in a contemporary, critical context and in the light of current social issues. -

\(Cont'd-020310-Heart Sutra Transcribing\)

The Heart of Perfect Wisdom— Lecture on The Heart of Prajñā Pāramitā Sutra (part 2) Transcribed and edited from a talk given by Ven. Jian-Hu on March 10, 2002 at Buddha Gate Monastery ©2002 Buddha Gate Monastery•For Free Distribution Only Translation of Sanskrit Words When Buddhism came to China about two thousand years ago, the Indian Buddhist masters cooperated with the Chinese masters and set up some rules on translation. They were meticulous about the translation process. One of the rules is that if the word has multiple meanings then it should not be translated because if we translate it one way we lose its other meanings. Another rule is that if the Sanskrit word doesn’t have a corresponding concept in Chinese, then it is not translated. Prajñā, nirvana, and skandha are Sanskrit words. Skandha has multiple meanings. There is no corresponding word to explain prajñā or nirvana either in Chinese, or in English. Does anyone know what nirvana is? Well, some 6th grader knows! Last week when I was invited to an intermediate school to introduce Buddhism, I asked, “What is nirvana?” One child said, “I know, it’s a rock band!” Another child raised his hand and said, “nirvana is ultimate peace.” I was really surprised. That is a really good way to describe nirvana – ultimate peace. The Five Skandhas Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara, while deeply immersed in prajñā pāramitā, clearly perceived the empty nature of the five skandhas, and transcended all suffering. Skandha is a Sanskrit word and it means aggregate. Aggregate is an assembly of things. -

Chapter One an Introduction to Jainism and Theravada

CHAPTER ONE AN INTRODUCTION TO JAINISM AND THERAVADA BUDDfflSM CHAPTER-I An Introduction to Jainism and Theravada Buddhism 1. 0. History of Jainism "Jainism is a system of faith and worship. It is preached by the Jinas. Jina means a victorious person".' Niganthavada which is mentioned in Buddhist literature is believed to be "Jainism". In those days jinas perhaps claimed themselves that they were niganthas. Therefore Buddhist literature probably uses the term 'nigantha' for Jinas. According to the definition of "Kilesarahita mayanti evamvaditaya laddhanamavasena nigantho" here nigantha (S. nkgrantha) means those who claimed that they are free from all bonds.^ Jainism is one of the oldest religions of the world. It is an independent and most ancient religion of India. It is not correct to say that Jainism was founded by Lord Mahavlra. Even Lord Parsva cannot be regarded as the founder of this great religion. It is equally incorrect to maintain that Jainism is nothing more than a revolt against the Vedic religion. The truth is that Jainism is quite an independent religion. It has its own peculiarities. It is flourishing on this land from times immemorial. Among Brahmanic and i^ramanic trends, Jainism, like Buddhism, represents ^ramanic culture. In Buddhist literatures, we can find so many 'GJ, 1 ^ DNA-l, P. 104 informations about Jainism. The Nigantha Nataputta is none else but Lord Mahavlra.^ 1.1. Rsabhadeva According to tradition, Jainism owes its origin to Rsabha, the first among the twenty-four Tirthankaras. The rest of the Trrthahkaras are said to have revived and revealed this ancient faith from time to time. -

1 Syllabus for Higher Diploma Course In

Syllabus for Higher Diploma Course in Buddhist Studies (A course applicable to students of the University Department) From the Academic Year 2020–2021 Approved by the Ad-hoc Board of Studies in Pali Literature and Culture Savitribai Phule Pune University 1 Savitribai Phule Pune University Higher Diploma Course in Buddhist Studies General Instructions about the Course, the Pattern of Examination and the Syllabus I. General Instructions I.1 General Structure: Higher Diploma Course in Buddhist Studies is a three-year course of semester pattern. It consists of six semesters and sixteen papers of 50 marks each. I.2 Eligibility: • Passed Advanced Certificate Course in Buddhist Studies • Passed H.S.C. or any other equivalent examination with Sanskrit / Pali / Chinese / Tibetan as one subject. I.3 Duration: Three academic years I.4 Fees: The Admission fee, the Tuition Fee, Examination Fee, Record Fee, Statement of Marks for each year of the three-year Higher Diploma course will be as per the rules of the Savitribai Phule Pune University. I.5 Teaching: • Medium of instruction - English or Marathi • Lectures: Semesters I and II - Four lectures per week for fifteen weeks each Semesters III to VI – Six lectures per week for fifteen weeks each II Pattern of Examination II.1 Assessment and Evaluation: • Higher Diploma Course examination will be held once at the end of each semester of the academic year. • The examination for the Higher Diploma Course will consist of an external examination carrying 40 marks of two hours duration and an internal examination of 10 marks for all the sixteen papers. -

Lankavatara-Sutra.Pdf

Table of Contents Other works by Red Pine Title Page Preface CHAPTER ONE: - KING RAVANA’S REQUEST CHAPTER TWO: - MAHAMATI’S QUESTIONS I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XIII XIV XV XVI XVII XVIII XIX XX XXI XXII XXIII XXIV XXV XXVI XXVII XXVIII XXIX XXX XXXI XXXII XXXIII XXXIV XXXV XXXVI XXXVII XXXVIII XXXIX XL XLI XLII XLIII XLIV XLV XLVI XLVII XLVIII XLIX L LI LII LIII LIV LV LVI CHAPTER THREE: - MORE QUESTIONS LVII LVII LIX LX LXI LXII LXII LXIV LXV LXVI LXVII LXVIII LXIX LXX LXXI LXXII LXXIII LXXIVIV LXXV LXXVI LXXVII LXXVIII LXXIX CHAPTER FOUR: - FINAL QUESTIONS LXXX LXXXI LXXXII LXXXIII LXXXIV LXXXV LXXXVI LXXXVII LXXXVIII LXXXIX XC LANKAVATARA MANTRA GLOSSARY BIBLIOGRAPHY Copyright Page Other works by Red Pine The Diamond Sutra The Heart Sutra The Platform Sutra In Such Hard Times: The Poetry of Wei Ying-wu Lao-tzu’s Taoteching The Collected Songs of Cold Mountain The Zen Works of Stonehouse: Poems and Talks of a 14th-Century Hermit The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma P’u Ming’s Oxherding Pictures & Verses TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE Zen traces its genesis to one day around 400 B.C. when the Buddha held up a flower and a monk named Kashyapa smiled. From that day on, this simplest yet most profound of teachings was handed down from one generation to the next. At least this is the story that was first recorded a thousand years later, but in China, not in India. Apparently Zen was too simple to be noticed in the land of its origin, where it remained an invisible teaching. -

Time and Eternity in Buddhism

TIME AND ETERNITY IN BUDDHISM by Shoson Miyamoto This essay consists of three main parts: linguistic, historical and (1) textual. I. To introduce the theory of time in Buddhism, let us refer to the Sanskrit and Pali words signifying "time". There are four of these: sa- maya, kala, ksana (khana) and adhvan (addhan). Samaya means a coming together, meeting, contract, agreement, opportunity, appointed time or proper time. Kala means time in general, being employed in the term kala- doctrine or kala-vada, which holds that time ripens or matures all things. In its special meaning kala signifies appointed or suitable time. It may also mean meal-time or the time of death, since both of these are most critical and serious times in our lives. Death is expressed as kala-vata in Pali, that is "one has passed his late hour." Ksana also means a moment, (1) The textual part is taken from the author's Doctoral Dissertation: Middle Way thought and Its Historical Development. which was submitted to the Imperial University of Tokyo in 1941 and published in 1944 (Kyoto: Hozokan). Material used here is from pp. 162-192. Originally this fromed the second part of "Philosophical Studies of the Middle," which was delivered at the Annual Meeting of the Philosophical Society, Imperial University of Tokyo, in 1939 and published in the Journal of Philosophical Studies (Nos. 631, 632, 633). Since at that time there was no other essay published on the time concept in Buddhism, these earlier studies represented a new and original contribution by the author. Up to now, in fact, such texts as "The Time of the Sage," "The Pith and Essence" have survived untouched. -

Buddhist Psychology

CHAPTER 1 Buddhist Psychology Andrew Olendzki THEORY AND PRACTICE ince the subject of Buddhist psychology is largely an artificial construction, Smixing as it does a product of ancient India with a Western movement hardly a century and a half old, it might be helpful to say how these terms are being used here. If we were to take the term psychology literally as referring to “the study of the psyche,” and if “psyche” is understood in its earliest sense of “soul,” then it would seem strange indeed to unite this enterprise with a tradition that is per- haps best known for its challenge to the very notion of a soul. But most dictio- naries offer a parallel definition of psychology, “the science of mind and behavior,” and this is a subject to which Buddhist thought can make a significant contribution. It is, after all, a universal subject, and I think many of the methods employed by the introspective traditions of ancient India for the investigation of mind and behavior would qualify as scientific. So my intention in using the label Buddhist Psychology is to bring some of the insights, observations, and experi- ence from the Buddhist tradition to bear on the human body, mind, emotions, and behavior patterns as we tend to view them today. In doing so we are going to find a fair amount of convergence with modern psychology, but also some intriguing diversity. The Buddhist tradition itself, of course, is vast and has many layers to it. Al- though there are some doctrines that can be considered universal to all Buddhist schools,1 there are such significant shifts in the use of language and in back- ground assumptions that it is usually helpful to speak from one particular per- spective at a time. -

THE AJIVIKAS a Short History of Their Religion Ami Philosophy

THE AJIVIKAS A Short History of their Religion ami Philosophy PART I HISTORICAL SUMMARY Introductio n The History of the Ajivikas can broadly he divided into three periods in conformity with the three main ntasres of development through which their doctrines had passed. The general facts about these periods are summed up below with a view to indicate the precise nature of the problems that confront us in the study of each. The periods and problems are as follows: — 1. PRE-MAKKIIAM PERIOD. Problems.- -The rise of a religious order of wander- ins? mendicants called the Ajlvika from a Vanaprastha or Vaikhanasa order of the hermits, hostile alike in attitude towards the religion of the Brahmans and the Vaikhanasas, bearing yet some indelible marks of the parent asrama ; a higher synthesis in the new Bhiksu order of the three or four ilsrama* of the Brahmans. 2. MAKKHAM PERIOD. Problems.— Elevation of Ajlvika religion into a philosophy of life at the hands of Makkhali 2 THE AJIVIKAS Gosala; his indebtedness to his predecessors, relations with the contemporary Sophists, and originality of conception. 3. POST-MAKKHALI PERIOD. Problems—The further development of Ajivika religion, the process of Aryan colonisation in India, the spread of Aryan culture, the final extinction of the sect resulting from gradual transformation or absorption of the Ajivika into the Digambara Jaina, the Shivaitc and others; other causes of the decline of the faith; the influence of Ajivika religion and philosophy on Jainism, Buddhism and Hinduism; determination of the general character of a history of Indian religion. 1. PKE-MAKKHALI PERIOD.